Russian Copper Icons Crosses Kunz Collection: Castings Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

Sign of the Son of Man.”

Numismatic Evidence of the Jewish Origins of the Cross T. B. Cartwright December 5, 2014 Introduction Anticipation for the Jewish Messiah’s first prophesied arrival was great and widespread. Both Jewish and Samaritan populations throughout the known world were watching because of the timeframe given in Daniel 9. These verses, simply stated, proclaim that the Messiah’s ministry would begin about 483 years from the decree to rebuild Jerusalem in 445BC. So, beginning about 150 BC, temple scribes began placing the Hebrew tav in the margins of scrolls to indicate those verses related to the “Messiah” or to the “Last Days.” The meaning of the letter tav is “sign,” “symbol,” “promise,” or “covenant.” Shortly after 150 BC, the tav (both + and X forms) began showing up on coins throughout the Diaspora -- ending with a flurry of the use of the symbol at the time of the Messiah’s birth. The Samaritans, in an effort to remain independent of the Jewish community, utilized a different symbol for the anticipation of their Messiah or Tahib. Their choice was the tau-rho monogram, , which pictorially showed a suffering Tahib on a cross. Since the Northern Kingdom was dispersed in 725 BC, there was no central government authority to direct the use of the symbol. So, they depended on the Diaspora and nations where they were located to place the symbol on coins. The use of this symbol began in Armenia in 76 BC and continued through Yeshua’s ministry and on into the early Christian scriptures as a nomina sacra. As a result, the symbols ( +, X and ) were the “original” signs of the Messiah prophesied throughout scriptures. -

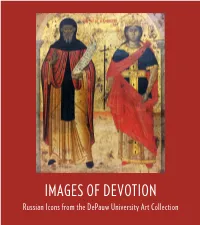

Images of Devotion

IMAGES OF DEVOTION Russian Icons from the DePauw University Art Collection INTRODUCTION Initially conceived in the first century, religious icons have a long history throughout the Christian world.1 The icon was not simply created to mirror the physical appearance of a biblical figure, but to idealize him or her, both physically and spiritually.2 Unlike Western Christianity where religious art can be appreciated solely for its beauty and skill alone, in the Orthodox tradition, the icon becomes more than just a reflection – it is a vehicle for the divine essence contained within.3 Due to the sacred nature of the icon, depictions of biblical figures became not only desirable in the Orthodox tradition, but an absolute necessity. Religious icons were introduced to Russia during the official Christianization of the country under Vladimir, the Great Prince of Kiev, in 988. After this period, many regional schools developed their own indigenous styles of icon painting, such as: Pokov, Novgorod, Moscow, Suzdal, and Jaroslavl.4 Upon Moscow’s emergence as Christ with Twelve Apostles the religious and political capital of Russia in the Russian Artist, Date Unknown Tempura Paint on Panel sixteenth century, it cemented its reputation as DePauw Art Collection: 1976.31.1 the great center for icon painting. Gift of Earl Bowman Marlatt, Class of 1912 The benefactor of this collection of Russian This painting, Christ with Twelve Apostles, portrays Jesus Christ iconography, Earl Bowman Marlatt (1892-1976), reading a passage from the Gospel of Matthew to his Apostles.7 was a member of the DePauw University class Written in Old Church Slavonic, which is generally reserved of 1912. -

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations

THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Department for External Church Relations His Holiness Patriarch Kirill meets with President of the Latvian Republic Valdis Zatlers On 20 December 2010, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church met with the President of the Latvian Republic, Valdis Zatlers. The meeting took place at the Patriarch's working residence in Chisty sidestreet, Moscow. The Latvian President was accompanied by his wife Ms. Lilita Zatlers; Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Latvian Republic to the Russian Federation Edgars Skuja; head of the President's Chancery Edgars Rinkevichs; state secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Andris Teikmanis; Riga Mayor Nil Ushakov; foreign relations advisor to the President, Andris Pelsh; and advisor to the President, Vasily Melnik. Taking part in the meeting were also Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate's Department for External Church Relations; Metropolitan Alexander of Riga and All Lat via; and Bishop Alexander of Daugavpils. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Russian Federation to the Latvian Republic A. Veshnyakov and the third secretary of the Second European Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs S. Abramkin represented the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia cordially greeted the President of Latvia and his suite, expressing his hope for the first visit of Valdis Zatlers to Moscow to serve to the strengthening of friendly relations between people of the two countries. His Holiness noted with appreciation the high level of relations between the Latvian Republic and the Russian Orthodox Church. "It is an encouraging fact that the Law on the Latvian Orthodox Church has come into force in Latvia in 2008. -

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Thomas De Simone, B.A., M.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Nicholas Breyfogle, Advisor David Hoffmann Robin Judd Predrag Matejic Copyright by Peter T. De Simone 2012 Abstract In the mid-seventeenth century Nikon, Patriarch of Moscow, introduced a number of reforms to bring the Russian Orthodox Church into ritualistic and liturgical conformity with the Greek Orthodox Church. However, Nikon‘s reforms met staunch resistance from a number of clergy, led by figures such as the archpriest Avvakum and Bishop Pavel of Kolomna, as well as large portions of the general Russian population. Nikon‘s critics rejected the reforms on two key principles: that conformity with the Greek Church corrupted Russian Orthodoxy‘s spiritual purity and negated Russia‘s historical and Christian destiny as the Third Rome – the final capital of all Christendom before the End Times. Developed in the early sixteenth century, what became the Third Rome Doctrine proclaimed that Muscovite Russia inherited the political and spiritual legacy of the Roman Empire as passed from Constantinople. In the mind of Nikon‘s critics, the Doctrine proclaimed that Constantinople fell in 1453 due to God‘s displeasure with the Greeks. Therefore, to Nikon‘s critics introducing Greek rituals and liturgical reform was to invite the same heresies that led to the Greeks‘ downfall. -

Cast a Cold Eye: the Late Works of Andy Warhol

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y October 11, 2006 PRESS RELEASE GAGOSIAN GALLERY GAGOSIAN GALLERY 555 WEST 24TH STREET 522 WEST 21ST STREET NEW YORK NY 10011 NEW YORK NY 10011 T. 212.741.1111 T. 212.741.1717 F. 212.741.9611 F. 212.741.0006 GALLERY HOURS: Tue – Sat 10:00am–6:00pm ANDY WARHOL: Cast a Cold Eye: The Late Works of Andy Warhol Wednesday, October 25 – Friday, December 22, 2006 Opening reception: Wednesday, October 25th, from 6 – 8pm “If you want to know about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” --Andy Warhol Gagosian Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition "Cast a Cold Eye: The Late Work of Andy Warhol.” The extensive exhibition, which occupies all galleries at 555 West 24th Street as well as a new gallery at 522 West 21st Street, draws together many of Warhol’s most iconic paintings from the following series executed during the 70s and 80s: Mao, Ladies & Gentlemen, Hammer & Sickle, Skulls, Guns, Knives, Crosses, Reversals, Retrospectives, Shadows, Rorschach, Camouflage, Oxidation, The Last Supper, Self Portraits and more. Comprised of works from the last eighteen years of Warhol’s life, “Cast a Cold Eye…” includes masterpieces that have been rarely or never before seen in New York, as well as important loans from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Andy Warhol Museum, and private collections. In his later career, Warhol was often vilified by art critics for being little more than a society portraitist and social impresario. -

The Cross and the Crucifix by Steve Ray

The Cross and the Crucifix by Steve Ray Dear Protestant Friend: You display a bare cross in your homes; we display the cross and the crucifix. What is the difference and why? The cross is an upright post with a crossbeam in the shape of a “T”. A crucifix is the same, but it has Christ’s body (corpus) attached to the cross. As an Evangelical Protestant I rejected the crucifix—Christ was no longer on the cross but had ascended to heaven. So why do I now tremble in love at the site of a crucifix? Let’s examine the history and issues surrounding the two. I will start with the Old Testament and the Jews’ use of images and prohibition of idols. I know in advance that it is not a thorough study, but it will give a general overview of the issues. I will try to provide a brief overview of the Cross and the Crucifix, the origin, the history, and the differing perspectives of Catholic and Protestant. It will try to catch the historical flow and include the pertinent points. The outline is as follows: 1. The Three Main Protestant Objections to the Crucifix 2. Images and Gods in the Old Testament 3. Images and Images of Christ in the New Testament 4. The Cross in the First Centuries 5. The Crucifix Enters the Picture 6. The “Reformation” and Iconoclasm 7. Modern Anti-Catholics and the Crucifix 8. Ecumenical Considerations The Three Main Protestant Objections to the Crucifix Let me begin by defining “Protestant” as used in this article. -

Download Download

Journal of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music Vol. 4 (1), Section II: Conference papers, pp. 83-97 ISSN 2342-1258 https://journal.fi/jisocm Stifling Creativity: Problems Born out of the Promulgation of the 1906 Tserkovnoje Prostopinije Fr Silouan Sloan Rolando [email protected] At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Greek Catholic Bishop of the city of Mukačevo in what is now Ukraine promulgated an anthology of Carpatho- Rusyn chant known as the Церковноє Простопѣніє (hereafter, the Prostopinije) or Ecclesiastical Plainchant. While this book follows in the tradition of printed Heirmologia found throughout the Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches of Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia starting in the sixteenth century, this book presents us with a number of issues that affect the quality and usability of this chant in both its homeland and abroad as well as in the original language, Old Church Slavonic, and in modern languages such as Ukrainian, Hungarian and English. Assuming that creativity is more than just producing new music out of thin air, the problems revealed in the Prostopinije can be a starting point the better to understand how creativity can be unintentionally stifled and what can be done to overcome these particular obstacles. A Brief History Heirmologia in this tradition are anthologies of traditional chant that developed in the emergence of the Kievan five-line notation in place of the older Znamenny neums. With the emergence of patterned chant systems variously called Kievan, Galician, Greek and Bulharski, each touting unique melodies for each tone and each element of liturgy, the Heirmologia would be augmented with these chants often replacing the older Znamenny, especially for the troparia, stichera and prokeimena of the Octoechos. -

Wavelength (November 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 11-1984 Wavelength (November 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (November 1984) 49 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I ~N0 . 49 n N<MMBER · 1984 ...) ;.~ ·........ , 'I ~- . '· .... ,, . ----' . ~ ~'.J ··~... ..... 1be First Song • t "•·..· ofRock W, Roll • The Singer .: ~~-4 • The Songwriter The Band ,. · ... r tucp c .once,.ts PROUDLY PR·ESENTS ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••••• • •• • • • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • •• •• • •• • • • •• ••• •• • • •• •••• ••• •• ••••••••••• •••••••••••• • • • •••• • ••••••••••••••• • • • • • ••• • •••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••• •••••• •• ••••••••••••••• •••••••• •••• .• .••••••••••••••••••:·.···············•·····•••·• ·!'··············:·••• •••••••••••• • • • • • • • ...........• • ••••••••••••• .....•••••••••••••••·.········:· • ·.·········· .....·.·········· ..............••••••••••••••••·.·········· ............ '!.·······•.:..• ... :-=~=···· ····:·:·• • •• • •• • • • •• • • • • • •••••• • • • •• • -

CHURCH and PEOPLE " Holyrussia," the Empire Is Called, and the Troops of The

CHAPTER V CHURCH AND PEOPLE " HOLYRussia," the Empire is called, and the troops of the Tsar are his " Christ-loving army." The slow train stops at a wayside station, and..among the grey cot- The Church. tages on the hillside rises a white church hardly supporting the weight of a heavy blue cupola. The train approaches a great city, and from behind factory chimneys cupolas loom up, and when the factory chimneys are passed it is the domes and belfries of the churches that dominate the city. " Set yourselves in the shadow of the sign of the Cross, O Russian folk of true believers," is the appeal that the Crown makes to the people at critical moments in its history. With these words began the Manifesto of Alexander I1 announcing the emancipation of the serfs. And these same words were used bfthose mutineers on the battleship Potenzkin who appeared before Odessa in 1905. The svrnbols of the Orthodox Church are set around Russian life like banners, like ancient watch- towers. The Church is an element in the national conscious- ness. It enters into the details of life, moulds custom, main- tains a traditional atmosphere to the influence of which a Russian, from the very fact that he is a Russian, involuntarily submits. A Russian may, and most Russian intelligents do, deny the Church in theory, but in taking his share in the collective life of the nation he, at many points, recognises the Ch'urch as a fact. More than that. In those borcler- lands of emotion that until life's end evade the control of toilsomely acquired personal conviction, the Church retains a foothold, yielding only slowly and in the course of generations to modern influences. -

Christian Apocalyptic Extremism: a Study of Two Cases

CHRISTIAN APOCALYPTIC EXTREMISM: A STUDY OF TWO CASES Alar Laats Ph.D. in Systematic Theology, Professor of Religious Studies, Tallinn University, Estonia, [email protected] ABSTRACT. The article treats two cases of large scale Christian extremism: the estaBlishment of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in China in the middle of the 19th century and the Russian Old Believers movement that started in the second half of the 17th century. In Both cases there were intense expectations of the end of the world. In Both cases their extreme actions were provoked By the violent activity of the state authorities. The extremism of the Chinese Christians was directed outside whereas the extreme Behaviour of the Russian Old Believers was directed first of all inside, towards themselves. One of the reasons of the difference in their actions was the difference in their respective theological thinking. Key words: Christian extremism, Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Russian Old Believers, eschatological figures, utopias and dystopias. There are various ways to classify the phenomena of extremism. One possiBility is to divide these phenomena into external and internal ones. In the first case the extremism is directed towards others. Its aim is to change the other, usually to reBuild the whole world. It can easily Become aggression. In the case of the internal extremism it is directed towards the extremists them- selves. Its aim can Be a withdrawal or a change of themselves. Sometimes it Becomes self-denial. The last one hundred years have mainly Been an era of the atheistic extremism. Tens of millions of people have perished in the concentration camps created By national socialist or communist extremists. -

The Impact of Religion on Ethnic Survival: Russian Old Believers in Al Aska

CALIFORNIA GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY Vol. XXXI, 1991 THE IMPACT OF RELIGION ON ETHNIC SURVIVAL: RUSSIAN OLD BELIEVERS IN AL ASKA Susan W. Hardwick istorical and cultural geographers have long been in Hterested in the processes of immigrant settlement and subsequent cultural change (Joerg, 1932; Jordan, 1966; Mannion, 1974, 1977; McQuillan, 1978; Ostergren, 1988; Swrerenga, 1985). However, except for limited studies of ethnicity in the central United States, very little has been ac complished to date on the significant relationship between religion and ethnic retention and sense of place (Jordan, 1980; Ostergren, 1981; Legreid and Ward, 1982). Russian Old Believers in North America offer a particularly fascinat ing case study for an investigation of the role of religion as a key variable in culture change. For over three hundred years, in Russia, China, South America, and the United States, Old Believers have maintained their Russian lan guage, their religious beliefs, and their traditional lifestyle while living within very different, dominant majority cul tures (Colfer, 1985; Smithson, 1976). Will they continue to Dr. Hardwick received her Master's degree in Geography at California State University, Chico, and is now Associate Professor of Geography there. 19 20 THE CALIFORNIA GEOCRAPHER maintain their distinctive cultural and religious identity in Alaska in the 1990s? Regional Setting The tip of the Kenai Peninsula can barely be seen in the thick coastal fog. Glaciated peaks, fiorded coasts, and roar ing mountain streams dominate first impressions of this rolling, spruce-covered landscape. Old Believer settlements in Alaska are located in isolated, inaccessible places in three regions of the state of Alaska including Kenai forests, the Matanuska Valley, and islands just north of Kodiak (Figure 1).