Pacific ENSO Update Page 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Pacific Ocean – Tropical Cyclone ULA Ï

Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) – ECHO Daily Map | 08/01/2016 South Pacific Ocean Legend– Tropical Cyclone ULA Week rainfall (TRMM) TROPICAL CYCLONE LastValue 7 days acc. 30 Dec, 6.00 UTC SITUATION Legend(max. sustained winds) rainfall< 100 (NASA) mm 83 km/h sust. winds Cyclones> 118 Trackkm/h points 100 - 200 mm • Tropical Cyclone ULA formed over WIND_SPEED 63-118 km/h 200 - 300 mm (Pop. 187 800) the South Pacific Ocean on 30 Ï <0.000000 63 km/h - 17.000000 300 - 400 mm December 2015 and moved south- WIND BUFFER > 400 mm southwest, strengthening. It passed Ï 17.000001 - 32.500000 (Pop. 55 500) close to Vava'u islands (Tonga) on 1 >118 km/h Floods 92-118 km/h (Pop. 12 200) January 2016, with max. sustained 32.500001 - 69.000000 Ï 64-92 km/h Track uncertainty winds of 140 km/h and close to Lau Islands (Fiji) on 2-3 January, with Ï 69.000001 - 100.000000 max. sust. winds of 160-170 km/h. • Heavy rainfall and strong winds (Pop. 880 000) affected Fiji and Tonga during its 1 Jan, 18.00 UTC passage. Media reported minor 140 km/h sust. winds damage and evacuations in Tonga, 2 Jan, 18.00 UTC 167 km/h sust. winds as well as floods and damage in 8 Jan, 6.00 UTC 31 Dec, 18.00 UTC 102 km/h sust. winds some areas of Fiji. 9 Jan 18.00 UTC 167 km/h sust. winds (Pop. 283 000) • In the morning of 8 January, TC ULA 120 km/h sust. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Pdf | 618.14 Kb

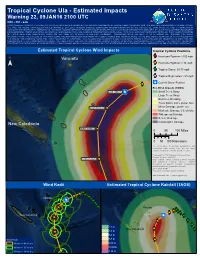

Tropical Cyclone Ula - Estimated Impacts Warning 22, 09JAN16 2100 UTC PDC - 06P - 22A [JTWC] Summary: TROPICAL CYCLONE (TC) 06P (ULA), LOCATED APPROXIMATELY 358 NM EAST-NORTHEAST OF NOUMEA, NEW CALEDONIA, HAS TRACKED SOUTHWESTWARD AT 06 KNOTS OVER THE PAST SIX HOURS. ANIMATED ENHANCED INFRARED SATELLITE IMAGERY SHOWED SIGNIFICANT INTENSIFICATION WITHIN THE CONVECTIVE CORE OVER THE PAST 6 HOURS WHICH SUPPORTS THE INCREASE IN INTENSITY TO 115 KNOTS. DVORAK INTENSITY ESTIMATES HAVE INCREASED TO T6.0 (115 KNOTS) FROM PGTW AND KNES. TC ULA IS ENCOUNTERING FAVORABLE ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS WITH LOW VERTICAL WIND SHEAR (VWS), SEA SURFACE TEMPERATURES (SSTS) NEAR 27 CELSIUS, AND GOOD DIVERGENT OUTFLOW. THE CURRENT POSITION IS PLACED WITH HIGH CONFIDENCE BASED ON THE 20NM EYE IN SATELLITE IMAGERY. FAVORABLE CONDITIONS OVER THE NEXT 12 TO 18 HOURS WILL SUPPORT CONTINUED INTENSIFICATION. THE CYCLONE IS TRACKING ALONG THE NORTHWESTERN PERIPHERY OF A DEEP-LAYERED SUB-TROPICAL RIDGE TO THE SOUTHEAST. NEAR TAU 24, TC 06P WILL REACH THE AXIS OF THE STEERING RIDGE AND TURN POLEWARD. AFTERWARDS, THE CYCLONE WILL ACCELERATE SOUTHEASTWARD WHERE IT WILL ENCOUNTER MODERATE TO HIGH VWS AND COOLING SSTS. THESE CONDITIONS WILL ERODE THE CORE STRUCTURE AND THE SYSTEM WILL RAPIDLY WEAKEN. TC ULA WILL FULLY DISSIPATE BY THE END OF THE FORECAST PERIOD AS IT INTERACTS WITH THE MID-LATITUDE WESTERLY FLOW. DYNAMIC MODEL GUIDANCE REMAINS IN TIGHT AGREEMENT WHICH SUPPORTS HIGH CONFIDENCE IN THE JTWC TRACK FORECAST. Estimated Tropical Cyclone Wind Impacts Tropical Cyclone Positions Ï Hurricane/Typhoon >150 mph Vanuatu Ï ¯ Hurricane/Typhoon > 74 mph Ï Tropical Storm: 39-73 mph Ï Ï Tropical Depression: <39 mph Ï )"Ï Current Storm Position 22SEP13 - 1800UTC Est. -

Hungry for Justice, Thirsty for Change CARITAS STATE of the ENVIRONMENT REPORT for OCEANIA 2016 Taveuni, Fiji

Hungry for justice, thirsty for change CARITAS STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR OCEANIA 2016 Wani Filipe ties climbing beans at Tutu Rural Training Centre, Taveuni, Fiji. CARITAS Hungry for justice, thirsty for change CARITAS STATE OF THE ENVIRONMENT REPORT FOR OCEANIA 2016 Monū’ia ā ka ko kinautolu ‘oku fie kaia mo fie inua ki he mā’oni’oní, he ’e faka makona ‘a kinautolu. Ka hoa te hunga e hiakai ana, e hiainu ana ki te tika; ka mākona hoki rātou. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice, for they will be satisfied. MATTHEW/MATIU 5:6 FEAST OF ST FRANCIS OF ASSISI 4 October 2016 Tutu ana te puehu Stirring up the dust Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand Caritas Tonga Caritas Australia PO Box 12193 Catholic Diocese of GPO Box 9830 Thorndon, Wellington 6144 Tonga and Niue Sydney, NSW 2001 Aotearoa New Zealand PO Box 1, Vaololoa Australia www.caritas.org.nz Nuku’alofa, Tonga www.caritas.org.au © Caritas Aotearoa New Zealand, Caritas Tonga and Caritas Australia Lead research and writing: Martin de Jong Writers and researchers: Amelia Ma’afu, Sarah Marland, Petra Wheatley Oversight and editing: Lisa Beech, Brendan Joyce Editing and proofing: Johanna Knox Design: Rose Miller Cover photo: Teriba of Nusabaruka, Gizo, Solomon Islands drinks water from a Caritas water project in response to the El Niño drought. The project had funding support from the New Zealand Aid Programme. Photo: Julianne Hickey. Staff assistance and photography: Crispin Anderlini, Cathy Bi, Dominic Boana, Nick Borthwick, Benjamin Breen, Nicole Clements, Sascha Costigan, Roger Ellis, Julianne Hickey, Stephanie Lalor, Mary Malagela, Mark Mitchell, Joe Moeono-Kolio, Patrice Moriarty, Paul O’Callaghan, Carl O’Sullivan, Anna Robertson-Bate, Murray Shearer, Joanna Viernes, Br Adrian Watson, Zachary Wone, Zhi Yan. -

Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network Natural Resource Data Series NPS/PACN/NRDS—2012/273 ON THE COVER Sunset at American Memorial Park (AMME), Saipan, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service staff. Annual Weather/Climate Data Summary 2010 Pacific Island Network Natural Resource Data Series NPS/PACN/NRDS—2012/273 Tonnie L. C. Casey National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring P.O. Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 April 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Data in this report were collected and analyzed using methods based on established, peer- reviewed protocols and were analyzed and interpreted within the guidelines of the protocols. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

Dear Friends

REPORT 2016 Dear friends, 33 degrees Celsius, 93 Fahrenheit, summer in the South Pacific and somebody is dreaming of a White Christmas, time to write our report for this year. After our extensive travels last year, see Report 2015 , we had planned to stay here and tend to house and garden. The last cyclone season from November 2015 to April 2016 was characterized by a very strong El Nino effect, the predictions were for more and stronger cyclones to occure in Tonga, but until the end of the last year everything stayed calm. All our neighbors on the island were gone, the dog, cats and chickens crowding around us. We had a quiet Christmas and New Year's Eve, but on the first day of 2016 cyclone ULA approached and was supposed to pass by Vava'u with up to 115 knots (200 km/h-125mph). We put on the cyclone shutters, brought the boat into the sheltered Hunga Lagoon, took down the solar panels and secured everything. In the night, the storm passed through with howling winds and a lot of rain, but only a few old trees came down and some banana plants, no major damages. The next two weeks passed by with the usual activities in house and garden. It was pretty hot, which limited our activities somewhat, spiders and heron were still busy. On Thursday, January 14., we went into town to get supplies, in the evening we watched a movie at home. Then I noticed colorful flashes in my right eye when I moved my head fast. -

The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands

At the very edge of a storm: The impact of a distant cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo and Ilan Noy SEF WORKING PAPER 24/2016 WORKING PAPERS IN ECONOMICS AND FINANCE School of Economics and Finance | Victoria Business School | www.victoria.ac.nz/sef The Working Paper series is published by the School of Economics and Finance to provide staff and research students the opportunity to expose their research to a wider audience. The opinions and views expressed in these papers are not necessarily reflective of views held by the school. Comments and feedback from readers would be welcomed by the author(s). Further enquiries to: The Administrator School of Economics and Finance Victoria University of Wellington P O Box 600 Wellington 6140 New Zealand Phone: +64 4 463 5353 Email: [email protected] Working Paper 24/2016 ISSN 2230-259X (Print) ISSN 2230-2603 (Online) At the Very Edge of a Storm: The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands Tauisi Taupo & Ilan Noy School of Economics & Finance Victoria University of Wellington October 2016 Abstract The intensity of cyclones in the Pacific is predicted to increase and sea levels are predicted to rise, so a small atoll nation like Tuvalu can serve as the ‘canary in the mine’ pointing to the new risks that are emerging because of climatic change. In Tuvalu, households are acutely vulnerable to storm surges caused by cyclones even if the cyclone itself passes very far away (in this case about a 1000km). Based on a survey we conducted in Tuvalu, we quantify the impacts of cyclone Pam (March 2015) on households, and the determinants of these impacts in terms of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and responsiveness. -

Cranking up the Intensity: Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events

CRANKING UP THE INTENSITY: CLIMATE CHANGE AND EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS CLIMATECOUNCIL.ORG.AU Thank you for supporting the Climate Council. The Climate Council is an independent, crowd-funded organisation providing quality information on climate change to the Australian public. Published by the Climate Council of Australia Limited ISBN: 978-1-925573-14-5 (print) 978-1-925573-15-2 (web) © Climate Council of Australia Ltd 2017 This work is copyright the Climate Council of Australia Ltd. All material Professor Will Steffen contained in this work is copyright the Climate Council of Australia Ltd Climate Councillor except where a third party source is indicated. Climate Council of Australia Ltd copyright material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia License. To view a copy of this license visit http://creativecommons.org.au. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the Climate Council of Australia Ltd copyright material so long as you attribute the Climate Council of Australia Ltd and the authors in the following manner: Cranking up the Intensity: Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events by Prof. Lesley Hughes Professor Will Steffen, Professor Lesley Hughes, Dr David Alexander and Dr Climate Councillor Martin Rice. The authors would like to acknowledge Prof. David Bowman (University of Tasmania), Dr. Kathleen McInnes (CSIRO) and Dr. Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick (University of New South Wales) for kindly reviewing sections of this report. We would also like to thank Sally MacDonald, Kylie Malone and Dylan Pursche for their assistance in preparing the report. Dr David Alexander Researcher, — Climate Council Image credit: Cover Photo “All of this sand belongs on the beach to the right” by Flickr user Rob and Stephanie Levy licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

Eradicating Poverty and Unifying Guyana

NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Eradicating Poverty and Unifying Guyana A Civil Society Document - AN OVERVIEW - I GUYANA - BASIC INFORMATION • Guyana, with an area of 83,000 square miles or 215,000 square kilometres, is located on the northern coast of South America, and is the only English-speaking country on that continent. It is bounded on the north by the Atlantic Ocean, on the east by Surinam, on the south and south-west by Brazil, and on the west and north-west by Venezuela. • Guyana is physically divided into four types of landforms: (i) a flat coastal, clayey belt which is about 4.5 feet below sea level, and in which most of its agricultural activity occurs; (ii) a sand belt, to the south of the coastal belt, which includes the Intermediate Savannas; (iii) an undulating, central peneplain which comprises more than half of the country’s area, and in which are located lush, almost pristine, tropical forests, and extensive mineral deposits. This landform stretches from the sand belt to the country’s southern boundary and encompasses, also, the Rupununi Savannas which border Brazil; and (iv) the highlands which are to be found in the midwestern area. This portion of the Guiana Highlands includes the Pakaraima mountain range. • Guyana has a plentitude of natural resources: fertile agricultural lands on the coastal plain and in the riverain areas; vast areas of tropical hardwood forests of various ecosystems and with a multitude of plant and animal species; abundant fish and shrimping grounds, both in its numerous rivers and in the Atlantic Ocean to its north; and a wide variety of minerals, including gold, diamonds, a range of semi-precious stones, bauxite and manganese. -

In and out of Suriname Caribbean Series

In and Out of Suriname Caribbean Series Series Editors Rosemarijn Hoefte (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Gert Oostindie (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) Editorial Board J. Michael Dash (New York University) Ada Ferrer (New York University) Richard Price (em. College of William & Mary) Kate Ramsey (University of Miami) VOLUME 34 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cs In and Out of Suriname Language, Mobility and Identity Edited by Eithne B. Carlin, Isabelle Léglise, Bettina Migge, and Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: On the road. Photo by Isabelle Léglise. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface issn 0921-9781 isbn 978-90-04-28011-3 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-28012-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by the Editors and Authors. This work is published by Koninklijke Brill NV. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff and Hotei Publishing. Koninklijke Brill NV reserves the right to protect the publication against unauthorized use and to authorize dissemination by means of offprints, legitimate photocopies, microform editions, reprints, translations, and secondary information sources, such as abstracting and indexing services including databases. -

Tuvalu: Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project

Initial Environmental Examination July 2016 Tuvalu: Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project Prepared by the Ministry of Communication and Transport for the Asian Development Bank. TA 8923 TUV: Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project - IEE ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected persons DOE – Department of Environment EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan GPS – global positioning system GRM – grievance redress mechanism HIV/AIDS – Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome IA – implementing agency IEE – initial environmental examination IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature MCT – Ministry of Communication and Transport NEMS – National Environmental Strategy PDA – project design advance PEAR – preliminary environmental assessment report PIU – project implementation unit PMU – project management unit PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance PSC – project supervision consultant SPREP – South Pacific Regional Environmental Program SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement (ADB) This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in