WESTERN FRONTIER OR FEUDAL SOCIETY?: METAPHORS and PERCEPTIONS of CYBERSPACE by Afred C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

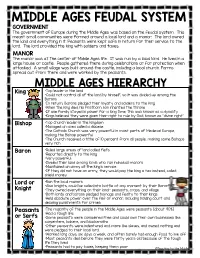

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1

Volume 21 Issue 1 1-1916 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1, 21 DICK. L. REV. 1 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol21/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dickinson Law Review VOL. XXI OCTOBER, 1916 No. 1 BUSINESS MANAGERS EDITORS John D. M. Royal, '17 Henry M. Bruner, '17 Lawrence D. Savige, '17 Edward H. Smith, '17 John H. Bonin, '17 William Lurio, '17 Joseph C. Paul, '18 Ethel Holderbaum, '18 Subscription $1.60 per annum, payable in advance WALLACE vs. EDWIN HARMSTAD, 44 PA. 492 In 1838 Arrison sold to four brothers Harmstad four adjoining lots, reserving out o2 each a yearly rent of !$60, payable half-yearly, in January and July. Each grantee, entered on his lot and built a house on it. The deeds were executed in duplicate each being signed by both parties. A part of the bargain was that the rents might be redeemed at any time. In the deeds was a blank with respect to the time of redemption, which was explained by Arrison as meaning that there was no limit of time. Some time after the delivery of the deeds, they were procured by Ar- rison for the alleged purpose of having them recorded, and while out of the possession of the Harmstads the blanks were filled with the words, "within ten years from the date thereof," making redemption after ten years impos- sible. -

Feudalism & Medieval Life

Feudalism & Medieval Life The Feudal System was introduced to England following the invasion and conquest of the island by William the Conqueror. The Feudal System had been used in France by the Normans from the time they first settled there around 900 AD. It was a simple, but effective system for the control of society by the King. All land was owned by the King, and one quarter was kept by as his personal property. Some land was given to the Catholic Church and the rest was leased out to others under strict controls. This means that others paid the king to use the land since he owned it. Land given to others was known as a fief. The King was in complete control under the Feudal System. He owned all the land in the country and decided who he would grant a fief to. He therefore only allowed those men he could trust to lease land from him. However, before they were given any land they had to swear an oath to remain faithful to the King. This was done at a formal and symbolic ceremony which was composed of the two-part act of loyalty and oath of fealty. The man receiving the fief then became a vassal of the king. Vassals who leased land from the King were sometimes known as Barons and were generally wealthy and powerful. The fiefs that Barons were granted by the King were governed by the manor system. The vassal was known as the Lord of the Manor and established his own system of justice, minted money and set up taxes. -

Land and Feudalism in Medieval England

Land and Feudalism in Medieval England by Magistra Rosemounde of Mercia Most people know that the feudal system controlled property ownership in England after the Norman conquest of 1066, but without a real understanding of what that means. Feudalism (the term was not actually used until the 17th century) was a social as well as an economic system. It combined elements of Germanic tradition with both Roman and Church law. It is a law of conquerors. The basis of English feudalism was that every person's position in society was defined through a relationship with land, because land was the major source of revenue and the real source of power. Prior to the Conquest, two types of land holdings were known in England: the Celtic, and later, the Germanic or Saxon. Under Celtic custom, all land was held by the sword. There were no legal institutions to protect ownership, only the owner's ability to hold it. Under the Saxon system, land ownership was tied to families. Land was not held of any superior and was not allowed to leave family possession. This form of holding was called folk-land. Folk-land was measured by dividing it into large counties that were then subdivided into hundreds. Later, as Saxon law was influenced by Roman law and the Christian Church, two other holdings developed: book-land, land that was a gift from a superior, and laen-land, land that was loaned to someone outside the family unit in exchange for something. This changed with the Norman conquest. William the Conqueror and his successors, claimed ownership of all the land in England, and everyone else held their land either directly or indirectly from the King. -

The Trust As an Instrument of Law Reform

YALE LAW JOURNAL Vol. XXXI MARCH, 1922 No. 5 THE TRUST AS AN INSTRUMENT OF LAW REFORM AUSTIN W. ScoTT Professor of Law, Harvard University Professor Maitland, in one of his most brilliant essays,' said: "The idea of a trust is so familiar to us all that we never wonder at it. And yet surely we ought to wonder. If we were asked what was the greatest and most distinctive achievement performed by Englishmen in the field of jurisprudence I cannot think that we could have any better answer to give than this, namely, the development from century to century of the trust idea." Maitland's dictum at first blush may seem to be an exaggeration, but when it is considered how much of the progress of the English law is due to the doctrines of the law of uses and trusts, its truth would seem to be clear. It was chiefly by means of uses and trusts that the feudal system was undermined in England, that the law of conveyancing was revolutionized, that the economic position of married women was ame- liorated, that family settlements have been effected, whereby daughters and younger sons of landed proprietors have been enabled modestly to participate in the family wealth, that unincorporated associations have found a measure of protection, that business enterprizes of many kinds have been enabled to accomplish their purposes, that great sums of money have been devoted to charitable enterprizes; and by employing the analogy of a trust, by the invention of the so-called constructive trust, the courts have been enabled to give relief against all sorts of fraudulent schemes whereby scoundrels have sought to enrich them- selves at the expense of other persons. -

The Salisbury Oath: Its Feudal Implications

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1943 The Salisbury Oath: Its Feudal Implications Harry Timothy Birney Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Birney, Harry Timothy, "The Salisbury Oath: Its Feudal Implications" (1943). Master's Theses. 53. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/53 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1943 Harry Timothy Birney THE SALISBURY OATH - ITS FEUDAL IMPLICATIONS by HARRY TIMOTHY BIRNEY, S.J., A.B. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY J~e 1943 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 CHAPTER I FEUDALI SM - IN THEORY • • • • • • • • • • • 3 II FEUDALISTIC TENDENCIES IN ENGLAND BEFORE 1066 ••••••••••••••••••••• 22 III NORMAN FEUDALISM BEFORE 1066 • • • • 44 IV ANGLO - NORMAN FEUDALISM PRECEDING THE OATH OF SALISBURy........... 62 V THE SALISBURY OATH • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 81 CONCLUSION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 94 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • -

Feudal System and Harrying of the North

Date: How did William control England after his successful conquest? Baron: Important landowners in Normandy (Similar to the Earls in England) Harrying: Frequently carrying out attacks Feudal System: A hierarchy of society (most important to least) with everyone having a role rewrite this correcting any mistakes you find – there are harold had to go up to stanford brige to have a fight with harald hardrada. This was about 250 miles. He then heard that William had sailed across and invaded. He had to march all the way back really quick. He left some trops. rewrite this correcting any mistakes you find – there are harold had to go up to stanford brige to have a fight with harald hardrada. This was about 250 miles. He then heard that William had sailed across and invaded. He had to march all the way back really quick. He left some trops. Harold had to go up to Stamford Bridge to have a fight with Harald Hardrada. This was about 300 miles. He then heard that William had sailed across and invaded. He had to march all the way back really quick. He left some troops. There were over c.1.5 million people living in England and William only had a few thousand soldiers. He needed to be in control and most importantly, he needed his baron’s support! This is why William introduced the Feudal System… What can you remember about the Feudal System from a few weeks ago? Copy these key terms: At this time, people believed that all the land in a kingdom Fealty: An oath of was given to the king by God. -

Feudal Baronies and Manorial Lordships

Feudal Baronies and Manorial Lordships The seven years of the Baronage operation on the Internet have seen two messages stressed repeatedly — first, that the only feudal baronies still held in baroniam and capable of being sold with their status intact are those of Scotland, and, second, that genuine manorial lordships are not titles of nobility, and their holders are not qualified to be styled “Lord” (as in “Lord Blogges” or “Lord Bloggeston”). Now as new Scottish legislation is intended to separate baronial titles from the land to which they have been tied for, in some cases, close to 900 years, and thus to allow them, in essence, to be traded in a manner similar to English manorial lordships (with all the risks that entails), many readers have written to ask for an explanation of what is happening and for our views on what will happen in the future. In response, this special edition of the Baronage magazine examines the nature of feudal baronies and manorial lordships. Feudalism and the Barony The feudal system was developed in the territories Charlemagne had ruled, and it was brought to Britain by the Norman Conquest. Under feudalism all land belongs to the King. He grants parts of it to his closest advisers and most powerful warriors, these being known as tenants-in-chief, and they in turn grant parts of their lands to others who could in turn let parts of their holdings. There is thus a chain – King, tenants-in-chief, tenants, sub-tenants. The basic unit of feudalism is the manor – which had existed in Britain before the Conquest but was readily absorbed into the feudal system. -

Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism In

QUIA EMPTORES, SUBINFEUDATION, AND THE DECLINE OF FEUDALISM IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND: FEUDALISM, IT IS YOUR COUNT THAT VOTES Michael D. Garofalo Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Chair Laura Stern, Committee Member Mickey Abel, Minor Professor Harold Tanner, Chair of the Department of History David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Garofalo, Michael D. Quia Emptores, Subinfeudation, and the Decline of Feudalism in Medieval England: Feudalism, it is Your Count that Votes. Master of Science (History), August 2017, 123 pp., bibliography, 121 titles. The focus of this thesis is threefold. First, Edward I enacted the Statute of Westminster III, Quia Emptores in 1290, at the insistence of his leading barons. Secondly, there were precedents for the king of England doing something against his will. Finally, there were unintended consequences once parliament passed this statute. The passage of the statute effectively outlawed subinfeudation in all fee simple estates. It also detailed how land was able to be transferred from one possessor to another. Prior to this statute being signed into law, a lord owed the King feudal incidences, which are fees or services of various types, paid by each property holder. In some cases, these fees were due in the form of knights and fighting soldiers along with the weapons and armor to support them. The number of these knights owed depended on the amount of land held. Lords in many cases would transfer land to another person and that person would now owe the feudal incidences to his new lord, not the original one. -

![The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I, Vol. 1 [1898]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8361/the-history-of-english-law-before-the-time-of-edward-i-vol-1-1898-3218361.webp)

The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I, Vol. 1 [1898]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Sir Frederick Pollock, The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I, vol. 1 [1898] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected].