Unit 21 Feudalism: Forms and Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 8: the Feudal System

The Artios Home Companion Series Unit 8: The Feudal System Teacher Overvie w AFTER THE Fall of Rome and the conquests and raids of the Vikings, the people of Europe needed protection and security. It was out of this need that the feudal system arose. Lesser lords and knights would pay tribute to more powerful nobles in exchange for their protection. While this may sound good in theory, the resulting system had its disadvantages, such as abuse of the poor. In this unit we will study the effects of feudalism. Miniature from the Queen Mary Psalter, c. 1310, of men harvesting wheat with reaping-hooks. It is a depiction of socage (paying rent in the form of labor) on the royal demesne (the land which was retained by a lord of the manor for his own use and support) in feudal England. Reading and Assignments Based on your student’s age and ability, the reading in this unit may be read aloud to the student and journaling and notebook pages may be completed orally. Likewise, other assignments can be done with an appropriate combination of independent and guided study. In this unit, students will: Complete one lesson in which they will learn about the feudal system. Define vocabulary words. Explore the following websites: ▪ The Middle Ages - The Feudal System: http://www.angelfire.com/hi5/interactive_learning/NormanConquest/t he_middle__ages.htm ▪ Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry: http://www.bayeuxtapestry.org.uk/ Visit www.ArtiosHCS.com for additional resources. Medieval to Renaissance: Elementary Unit 8: The Feudal System Page 76 Leading Ideas God orders all things for the ultimate good of His people. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin

NORTHERN IRELAND HERITAGE GARDENS TRUST OCCASIONAL PAPER, No 4 (2015) 'Without Rival in our Metropolitan County' - The History of Luttrellstown Demesne, Co. Dublin Terence Reeves-Smyth Luttrellstown demesne, which occupies around 600 acres within its walls, has long been recognised as the finest eighteenth century landscape in County Dublin and one of the best in Ireland. Except for the unfortunate incorporation of a golf course into the eastern portion of its historic parkland, the designed landscape has otherwise survived largely unchanged for over two centuries. With its subtle inter-relationship of tree belts and woodlands, its open spaces and disbursement of individual tree specimens, together with its expansive lake, diverse buildings and its tree-clad glen, the demesne, known as 'Woodlands' in the 19th century, was long the subject of lavish praise and admiration from tourists and travellers. As a writer in the Irish Penny Journal remarked in October 1840: ‘considered in connection with its beautiful demesne, [Luttrellstown] may justly rank as the finest aristocratic residence in the immediate vicinity of our metropolis.. in its natural beauties, the richness of its plantations and other artificial improvements, is without rival in our metropolitan county, and indeed is characterised by some features of such exquisite beauty as are rarely found in park scenery anywhere, and which are nowhere to be surpassed’.1 Fig 1. 'View on approaching Luttrellstown Park', drawn & aquatinted by Jonathan Fisher; published as plate 6 in Scenery -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Feudalism Manors

effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their Recognizing own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and politi- Effects cal strength. What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and A New Social Order: Feudalism Muslim invasions In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the on medieval head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) Europe? River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landhold- ing, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C.until 256 B.C.Feudalism in Japan began in A.D.1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. -

Part Two Feudal Institutions

Part Two Feudal Institutions Introduction Amid invasions from abroad and tumult at home, with the decay and near-disappearance of effective government, the men of the early Middle Ages faced a critical problem in supplying their basic social needs-food, protection, companionship. Under such peril ous conditions, the most immediate social unit which could offer support and protection to harassed individuals was the family. What was the nature of the family in early medieval society? This is a question which must be asked in any consideration of the feudal world, but it is surprisingly difficult to answer. Few and uninformative records cast but dim light on this central institution; they are enough to excite our interest but rarely sufficient to give firm responses to our questions. At one time the common view of historians was that the family of the early Middle Ages was characteristically large, extended or patriarchal. Married sons continued to live within their father's house or with one another after their parents' deaths; they sought security against external dangers primarily in their own large numbers. There is, to be sure, much evidence of strong family solidarity and sentiment in medieval society. A heavy moral obli gation, everywhere evident, lay upon family members to avenge the harm done to a kinsman. This is one of the principal themes of FEUDAL INSTITUTIONS the epic poem Raoul of Cambrai (Document 31), as it is of many medieval tales. The characters in it repeatedly assert that warriors who fail to seek vengeance are dastards and cowards, not worth a spur or a glove. -

Feudal Contract – Medieval Europe

FEUDAL CONTRACT – MEDIEVAL EUROPE Imagine you are living in Medieval Europe (500 – 1500). Despite the fact that a feudal contract is an unwritten contract, write out a feudal contract. You and a partner will take on the roles of lord and vassal: - You Need to Write Out the Contract: - The lord can have a certain title (i.e. duke/duchess, baron/baroness, or count/countess), and specify what social standing the vassal has (i.e. lower-level knight, peasant, etc.). - In your contract, specify how much acreage in land (fief) will be given to the vassal. - Specify how much military service the vassal will serve, and what kind of fighting they will do (i.e. cavalry, foot soldier…) - How much money will a vassal provide his lord if he is kidnapped, and if there is a ransom? How much will a vassal provide for one of the lord’s children’s weddings? (Specify money in terms of weight and precious metal such as “30 lbs. gold”). - Specify other duties from the readings (Feudalism HW and class handout) that will be done by a lord and vassal (i.e. the lord will give safety and will defend his vassal in court). - List any other duties a lord/vassal will do of your choosing. (i.e. farm a certain crop, make a certain craft) - Define feudalism, fief, knight, vassal, and serfs. - Sign and date your contract at the bottom to make it official, and make sure the date is between the year 500 and 1500. Example: Lord/Vassal Feudal Contract: I am a peasant (name of vassal) and will serve and be the vassal of (name of Lord/Duke). -

B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism Revised 21 October 2013

III. BARRIERS TO ECONOMIC GROWTH IN THE MEDIEVAL ECONOMY: B. Medieval Manorialism and Peasant Serfdom: the Agricultural Foundations of Medieval Feudalism revised 21 October 2013 Manorialism: definitions • (1) a system of dependent peasant cultivation, • in which a community of peasants, ranging from servile to free, received their lands or holdings from a landlord • - usually a feudal, military lord • (2) the peasants: worked those lands at least in part for the lord’s economic benefit • - in return for both economic and military security in holding their tenancy lands from that military lord. Medieval Manorialism Key Features • (1) European manorialism --- also known as seigniorialism [seignior, seigneur = lord] both predated and outlived feudalism: predominant agrarian socio-economic institution from 4th-18th century • (2) Medieval manorialism: links to Feudalism • The manor was generally a feudal fief • i.e., a landed estate held by a military lord in payment and reward for military services • Feudal fiefs were often collections of manors, • servile peasants provided most of labour force in most northern medieval manors (before 14th century) THE FEUDAL LORD OF THE MANOR • (1) The Feudal Lord of the Manor: almost always possessed judicial powers • secular lord: usually a feudal knight (or superior lord: i.e., count or early, duke, etc.); • ecclesiastical lord: a bishop (cathedral); abbot (monastery); an abbess (nunnery) • (2) Subsequent Changes: 15th – 18th centuries • Many manors, in western Europe, passed into the hands of non-feudal -

Farwell to Feudalism

Burke's Landed Gentry - The Kingdom in Scotland This pdf was generated from www.burkespeerage.com/articles/scotland/page14e.aspx FAREWELL TO FEUDALISM By David Sellar, Honorary Fellow, Faculty of Law, University of Edinburgh "The feudal system of land tenure, that is to say the entire system whereby land is held by a vassal on perpetual tenure from a superior is, on the appointed day, abolished". So runs the Sixth Act to be passed in the first term of the reconvened Scottish Parliament, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000. The Act is welcome. By the end of the second millennium the feudal system had long outlived its usefulness, even as a legal construct, and had few, if any defenders. As the Scottish Law Commission commented in 1999, "The main reason for recommending the abolition of the feudal system of land tenure is that it has degenerated from a living system of land tenure with both good and bad features into some-thing which, in the case of many but not all superiors, is little more than an instrument for extracting money". The demise of feudalism brings to an end a story which began almost a thousand years ago, and which has involved all of Scotland's leading families. In England the advent of feudalism is often associated with the Norman Conquest of 1066. That Conquest certainly marked a new beginning in landownership which paved the way for the distinctive Anglo-Norman variety of feudalism. There was a sudden and virtually clean sweep of the major landowners. By the date of the Domesday Survey in 1086, only two major landowners of pre-Conquest vintage were left south of the River Tees holding their land direct of the crown: Thurkell of Arden (from whom the Arden family descend), and Colswein of Lincoln. -

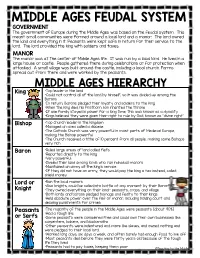

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Unit 8: the Feudal System

The Artios Home Companion Series Unit 8: The Feudal System Teacher Overview AFTER Charlemagne’s empire was broken up and Norsemen began to raid, Europe’s rulers needed to find a way to protect their lands and people from invading marauders and other enemies. Over time the feudal system developed, by which powerful lords offered protection to lesser lords, expecting service in return. Castle – a traditional symbol of a feudal society (Orava Castle in Slovakia) (By Wojsyl - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=101646) Reading and Assignments In this unit, students will: Complete two lessons in which they will learn about the rise of the feudal system, and feudal warfare, journaling and answering discussion questions as they read. Define vocabulary words. Medieval to Renaissance: Middle School Unit 8: The Feudal System Page 97 After each day’s reading, a wonderful time of exploration will be spent on the suggested websites dealing with feudalism and William the Conqueror or reading one of the library resources suggest the teacher or parent. ▪ The Middle Ages – The Feudal System: http://www.angelfire.com/hi5/interactive_learning/NormanConquest/t he_middle__ages.htm ▪ Britain’s Bayeux Tapestry: http://www.bayeuxtapestry.org.uk/ Be sure to visit www.ArtiosHCS.com for additional resources. Leading Ideas God orders all things for the ultimate good of His people. And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose. — Romans 8:28 Vocabulary Key People, Places, and Lesson 1: Events homage vassal recompense fealty adherent villein William the Conqueror serf Lesson 2: none Homage of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis Medieval to Renaissance: Middle School Unit 8: The Feudal System Page 98 L e s s o n O n e History Overview and Assignments The Feudal System “The root idea [of feudalism] was that all the land in a country belonged to the King, who held it from God alone; but of course no one man, king although he might be, could farm the land of a whole country. -

Issue Print Test | Nonsite.Org

ISSUE #12: CONTEMPORARY POLITICS AND HISTORICAL 12 REPRESENTATION nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2015 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren FOR AUTHORS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. 1 Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed.