<I>The Lord of the Rings</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University

Inklings Forever Volume 4 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fourth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 10 Lewis & Friends 3-2004 Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rearick, Anderson (2004) "Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc," Inklings Forever: Vol. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol4/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume IV A Collection of Essays Presented at The Fourth FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM ON C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2004 Upland, Indiana Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson Rearick, III Mount Vernon Nazarene University Rearick, Anderson. “Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc?” Inklings Forever 4 (2004) www.taylor.edu/cslewis 1 Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson M. Rearick, III The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien’s themselves out of sync with most of their peers, thus World1 underscoring the fact that Tolkien’s work has up until recently been the private domain of a select audience, In Jonathan Coe’s novel, The Rotters’ Club, a an audience who by their very nature may have confrontation takes place between two characters over inhibited serious critical examinations of Tolkien’s what one sees as racist elements in Tolkien’s Lord of work. -

The Hidden Meaning of the Lord of the Rings the Theological Vision in Tolkien’S Fiction

LITERATURE The Hidden Meaning of The Lord of the Rings The Theological Vision in Tolkien’s Fiction Joseph Pearce LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing J.R.R. Tolkien: The Man behind the Myth...........................................4 LECTURE 2 True Myth: Tolkien, C.S. Lewis & the Truth of Fiction.............................................8 Feature: The Use of Language in The Lord of the Rings............................................12 LECTURE 3 The Meaning of the Ring: “To Rule Them All, and in the Darkness Bind Them”.......................................14 LECTURE 4 Of Elves & Men: Fighting the Long Defeat.................................................................18 Feature: The Scriptural Basis for Tolkien’s Middle-earth............................................22 LECTURE 5 Seeing Ourselves in the Story: The Hobbits, Boromir, Faramir, & Gollum as Everyman Figures.......... 24 LECTURE 6 Of Wizards & Kings: Frodo, Gandalf & Aragorn as Figures of Christ..... 28 Feature: The Five Races of Middle-earth................................................................................32 LECTURE 7 Beyond the Power of the Ring: The Riddle of Tom Bombadil & Other Neglected Characters....................34 LECTURE 8 Frodo’s Failure: The Triumph of Grace......................................................................... 38 Suggested Reading from Joseph Pearce................................................................................42 2 The Hidden Meaning -

INTRODUCTION Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION Welcome to Mordor! The dark lord SauronTM is pleased that you have… chosen… to champion the true destiny of Middle-earthTM. Some prefer the hopeless cause of men and their miserable allies. Theirs is a fool’s choice! You show no affinity for such delusions. You seek glory for Sauron, and your rewards shall be great! You are one of Sauron’s most powerful minions: a Nazgul! You must work together with the other Nazgul to stop the cursed Hobbits and destroy the resistance of men. But at the same time, you must strive to prove your own worth to the dark lord. After all, there are rumors that even the Witch-king can be killed, and Sauron may soon need a new leader for the Nazgul! You are faced with three Campaigns you must conquer before the Ring-bearer carries The One Ring to Mount Doom. If you cannot complete them in time, all players lose! Along the way you will earn Victory Points (“VPs”). If you succeed in your duty, the player with the most VPs is the winner! Table of Contents Game Components 2-5 Battles: Aftermath 12 Setting Up The Game 6 A Sample Battle 13 Playing The Game 7-8 Mount Doom, Witch-king 15 Battles : Preparation 9 Winning the Game 15 Battles: Combat 10 Optional Rules 16 GAME COMPONENTS The Lord of the Rings: Nazgul includes the following: GAMEBOARD The Gameboard shows the three Campaigns you have been tasked Game Components List to complete: the defeat of Rohan, the conquest of Gondor, and the capture of the Ring-bearer. -

Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This Research Is a Product of the Graduate Program in English at Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1992 Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings Lisa Hillis This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hillis, Lisa, "Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings" (1992). Masters Theses. 2182. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2182 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for i,\1.clusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for iqclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Ef\i.stern Illinois University not allow my thes~s be reproduced because --------------- Date Author m Tolkien's Unnamed Deity Orchestrating the Lord of the Rings (TITLE) BY Lisa Hillis THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DECREE OF Master .of Arts 11': THE GRADUATE SCHOOL. -

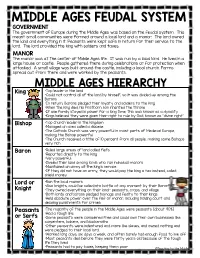

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

The Sense of Time in J.R.R. Tolkien's the Lord of the Rings

Volume 15 Number 1 Article 1 Fall 10-15-1988 The Sense of Time in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings Kevin Aldrich Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Aldrich, Kevin (1988) "The Sense of Time in J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 15 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol15/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses the importance of time, death, and/or immortality for various races of Middle-earth. Additional Keywords Death in The Lord of the Rings; Immortality in The Lord of the Rings; Time in The Lord of the Rings This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien TheBestNotes Study Guide by TheBestNotes Staff TheBestNotes.com Copyright © 2003, All Rights Reserved Distribution without the written consent of TheBestNotes.com is strictly prohibited. LITERARY ELEMENTS SETTING The Lord of the Rings is set in Middle-earth, a fictional world created by Tolkien. Mystical creatures such as hobbits, orcs, trolls, ents, elves, wangs, wizards, dragons, dwarves and men inhabit middle-earth. Middle-earth is a magical world in which imagination rules, but it exists very much like "real" society, with political and economic problems and power struggles. Each of the races that inhabit this world have their own territories and are distinct from one another. Part I is set in the Shire, a community of mostly hobbits. Bag End is in the Shire and is the home of Frodo, the hero. At the end of Part I, a group of travelling adventurers including Frodo leaves for Rivendell, an elf refuge. Part II takes place beyond the Shire in the rough worlds between Bag End and the citadel of Sarumon, the tower Orthanc at Isengard. It also takes place in the Tower of Sorcery, Minas Morgul, where the evil Sauron rules. Part III takes place in Mordor, a mountain range containing the volcano Orodruin. It also takes place on the road between Mordor and Bag End. The novel concludes just where it began, at Bag End. LIST OF CHARACTERS Major Characters Frodo Baggins The adopted heir of Bilbo Baggins. Frodo is chosen to destroy the Ring, and in the course of this mission, he proves to be a brave and intelligent leader. -

Treasures of Middle Earth

T M TREASURES OF MIDDLE-EARTH CONTENTS FOREWORD 5.0 CREATORS..............................................................................105 5.1 Eru and the Ainur.............................................................. 105 PART ONE 5.11 The Valar.....................................................................105 1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................ 2 5.12 The Maiar....................................................................106 2.0 USING TREASURES OF MIDDLE EARTH............................ 2 5.13 The Istari .....................................................................106 5.2 The Free Peoples ...............................................................107 3.0 GUIDELINES................................................................................ 3 5.21 Dwarves ...................................................................... 107 3.1 Abbreviations........................................................................ 3 5.22 Elves ............................................................................ 109 3.2 Definitions.............................................................................. 3 5.23 Ents .............................................................................. 111 3.3 Converting Statistics ............................................................ 4 5.24 Hobbits........................................................................ 111 3.31 Converting Hits and Bonuses...................................... 4 5.25 -

Analysis of Rhetoric in Aragorn's Speech at T

Jacob Cordell Dr. Heather Bryant 10/1/13 English 137H Aragorn, Hero and Rhetor: Analysis of rhetoric in Aragorn’s Speech at the Black Gate of Mordor in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings Sons of Gondor! Of Rohan! My brothers. I see in your eyes the same fear that would take the heart of me. A day may come when the courage of Men fails, when we forsake our friends and break all bonds of fellowship, but it is not this day. An hour of wolves and shattered shields when the Age of Men comes crashing down, but it is not this day! This day we fight! By all that you hold dear on this good earth, I bid you stand, Men of the West! To Tolkien lovers, fantasy fans and movie goers in general, Aragorn Elessar’s speech beneath the Black Gate is-dare I say it-as memorable as Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream Speech” or Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” You might shake your head and call it a sad case, but the comparison remains. What makes Aragorn’s speech so powerful that it not only sticks in the fans’ heads, but also moves nations to attack an indomitable foe, a demigod lacking a corporeal body, ruling an infinite supply of treacherous minions with an inconceivable unbridled hate that drives those minions and gives them strength beyond that of natural beings? Yes, Aragorn is fictional and the true creator of such intense rhetoric is not Aragorn in reality, but JRR Tolkien. But does it make the speech any less impressive? The lack of a realistic setting certainly does not change the rhetoric so for the purposes of this essay, I will refer to Aragorn as the rhetor through the voice of Vigo Mortenson, the actor who played Aragorn in Peter Jackson’s screenplay version of The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.