Rights of Reverter and Statute Quia Emptores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Scholarship Online

Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online The Oxford History of the Laws of England: Volume VI 1483–1558 John Baker Print publication date: 2003 Print ISBN-13: 9780198258179 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: March 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.001.0001 Uses, Wills, and Fiscal Feudalism Sir John Baker DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198258179.003.0035 Abstract and Keywords This chapter examines property law related to uses, wills, and fiscal feudalism in England during the Tudor period. It discusses the conflict between landlords and tenants concerning land use, feoffment, and land revenue. The prevalence of uses therefore provoked a conflict of interests which could not be reduced to a simple question of revenue evasion. This was a major problem because during this period, the greater part of the land of England was in feoffments upon trust. Keywords: fiscal feudalism, land use, feoffments, property law, tenants, wills, landlords ANOTHER prolonged discussion, culminating in a more fundamental and far-reaching reform, concerned another class of tenant altogether, the tenant by knight-service. Here the debate concerned a different aspect of feudal tenure, the valuable ‘incidents’ which belonged to the lord on the descent of such a tenancy to an heir. The lord was entitled to Page 1 of 40 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2014. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). -

Maternity's Wards: Investigations of Sixteenth Century Patterns of Maternal Gaurdianship

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU History Graduate Studies 2003 Maternity's Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns Of Maternal Gaurdianship Liz Woolcott Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd_history Part of the History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Woolcott, Liz, "Maternity's Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns Of Maternal Gaurdianship" (2003). History. 1. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd_history/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MATERNITY'S WARDS: INVESTIGATIONS OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY PATTERNS OF MATERNAL GUARDIANSHIP by Elizabeth B. W oolcott A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In HISTORY Approved: Dr. Norman Jones D~. Robert ijueller Major Professor Committee Member . Dr.,Nancy~~ V :m?fflo-;nas L. Ke~;· Committee~ber Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Log~ Utah 2003 11 Copyright © Elizabeth B. Woolcott 2003 All Rights Reserved 111 ABSTRACT Maternity' s Wards: Investigations Of Sixteenth Century Patterns of Maternal Guardianship by Elizabeth B. Woolcott, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2003 Major Professor: Dr. Nonnan Jones Department: History Grants of wardship, by the time of the Tudor period in England, had evolved into an institution divorced from its feudal foundation but committed to maintaining a goal of economic profit. Mixed with a pronounced responsibility of the monarch to care for the unprotected children of deceased feudatories, this goal compromised the practice of wardship grants and created a bureaucracy whose sole policy was patronage. -

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Trial by Battle*

Trial by Battle Peter T. Leesony Abstract For over a century England’s judicial system decided land disputes by ordering disputants’legal representatives to bludgeon one another before an arena of spectating citizens. The victor won the property right for his principal. The vanquished lost his cause and, if he were unlucky, his life. People called these combats trials by battle. This paper investigates the law and economics of trial by battle. In a feudal world where high transaction costs confounded the Coase theorem, I argue that trial by battle allocated disputed property rights e¢ ciently. It did this by allocating contested property to the higher bidder in an all-pay auction. Trial by battle’s “auctions” permitted rent seeking. But they encouraged less rent seeking than the obvious alternative: a …rst- price ascending-bid auction. I thank Gary Becker, Omri Ben-Shahar, Peter Boettke, Chris Coyne, Ariella Elema, Lee Fennell, Tom Ginsburg, Mark Koyama, William Landes, Anup Malani, Jonathan Masur, Eric Posner, George Souri, participants in the University of Chicago and Northwestern University’s Judicial Behavior Workshop, the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and especially Richard Posner and Jesse Shapiro for helpful suggestions and conversation. I also thank the Becker Center on Chicago Price Theory at the University of Chicago, where I conducted this research, and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. yEmail: [email protected]. Address: George Mason University, Department of Economics, MS 3G4, Fairfax, VA 22030. 1 “When man is emerging from barbarism, the struggle between the rising powers of reason and the waning forces of credulity, prejudice, and custom, is full of instruction.” — Henry C. -

STATUTE QUIA EMPTORES (1290) Statutes of the Realm, Vol

STATUTE QUIA EMPTORES (1290) Statutes of the Realm, vol. I, p . I 06. Whereas the buyers of lands and tenements belonging to the fees of great men and other [lords] have in times past often entered [those] fees to [the lords'] prejudice, because tenants holding freely of those great men and other [lords] have sold their lands and tenements [to those buyers] to hold in fee to [the buyers] and their heirs of their feoffors and not of the chief lords of the fees, with the result that the same chief lords have often lost the escheats, marriages and wardships of lands and tenements belonging to their fees; and this has seemed to the same great men and other lords [not only] very bard and burdensome [but also] in such a case to their manifest disinheritance: The lord king in his parliament at Westminster after Easter in 10 Tenure: services and incidents the eighteenth. year of his reign, namely a fortnight after the feast of St John the Baptist, at the instance of the great men of his realm, has granted, provided and laid down that from henceforth it shall be lawful for any free man at his own pleasure to sell his lands or tenements or [any] part of them; provided however that the feoffee shall hold those lands or tenements of the same chief lord and by the same services and customary dues as his feoffor previously held them. And if he sells to another any part of his same lands or tenements, the feoffee shall hold that [part] directly of the chief lord and shall immediately be burdened with such amount of service as belongs or ought to belong to the same lord for that part according to the amount of the land or tenement [that has been] sold; and so in this case that part of the service falls to the chief lord to be taken by the hand of the [feoffee], so that the feoffee ought to look and answer to the same chief lord for that part of the service owed as [is proportional to] the amount of the land or tenement sold. -

Farwell to Feudalism

Burke's Landed Gentry - The Kingdom in Scotland This pdf was generated from www.burkespeerage.com/articles/scotland/page14e.aspx FAREWELL TO FEUDALISM By David Sellar, Honorary Fellow, Faculty of Law, University of Edinburgh "The feudal system of land tenure, that is to say the entire system whereby land is held by a vassal on perpetual tenure from a superior is, on the appointed day, abolished". So runs the Sixth Act to be passed in the first term of the reconvened Scottish Parliament, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000. The Act is welcome. By the end of the second millennium the feudal system had long outlived its usefulness, even as a legal construct, and had few, if any defenders. As the Scottish Law Commission commented in 1999, "The main reason for recommending the abolition of the feudal system of land tenure is that it has degenerated from a living system of land tenure with both good and bad features into some-thing which, in the case of many but not all superiors, is little more than an instrument for extracting money". The demise of feudalism brings to an end a story which began almost a thousand years ago, and which has involved all of Scotland's leading families. In England the advent of feudalism is often associated with the Norman Conquest of 1066. That Conquest certainly marked a new beginning in landownership which paved the way for the distinctive Anglo-Norman variety of feudalism. There was a sudden and virtually clean sweep of the major landowners. By the date of the Domesday Survey in 1086, only two major landowners of pre-Conquest vintage were left south of the River Tees holding their land direct of the crown: Thurkell of Arden (from whom the Arden family descend), and Colswein of Lincoln. -

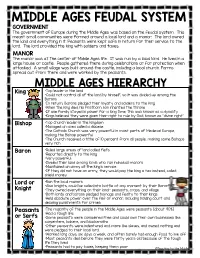

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Novel Disseisin5 Was Instituted As a Possessory Protection of Freehold Property Rights

IV–42 THE AGE OF PROPERTY: THE ASSIZES OF HENRY II SEC. 4 75. ?1236. “The fees of those who hold of the lord king in chief within the liberty of St. Edmunds to whom the lord king does not write.... Hugh de Polstead holds two fees and two parts of a fee in Polstead of the honour of Rayleigh [Essex].” The Book of Fees 1:600. (This document is probably connected with what is variously called an ‘aid’ or a ‘scutage’ which was levied on the occasion of the marriage of Isabella, Henry III’s sister, to the Emperor Frederick II in July of 1235. The lord of the honour of Rayleigh was Hubert de Burgh, Henry III’s justiciar, from 1215 until his downfall in 1232. The honour was in an ambiguous status in 1236; from 1237 it was in the king’s hands, as it was from 1163 to 1215. Sanders, English Baronies 139.) 76. 1242 X 1243. Surrey. “Of the honour of William de Windsor. Hugh de Polstead holds a half a knights fee in Compton of the same honour.” Id. 2 (1923) 685. (This is a document connected with the great scutage raised in connection with Henry III’s expedition to Gascony in 1242. The honour of William de Windsor was one-half of the honour of Eton [Bucks]. His father, also William, and his father’s cousin Walter had divided the honour in 1198 after fifteen years in which the inheritance had been disputed. Walter’s portion passed to his sisters Christiana and Gunnor in 1203, the latter of whom was married to ?Hugh I de Hosdeny. -

Statutes As Judgments: the Natural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England*

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1977 Statutes as Judgments: The aN tural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England Morris S. Arnold Indiana University School of Law - Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Legal History Commons, and the Natural Law Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Morris S., "Statutes as Judgments: The aN tural Law Theory of Parliamentary Activity in Medieval England" (1977). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 1136. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1136 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977] STATUTES AS JUDGMENTS: THE NATURAL LAW THEORY OF PARLIAMENTARY ACTIVITY IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND* MORRIS S. ARNOLD t The proposition that late medieval English lawgivers believed themselves to be exercising a declarative function has been so fre- quently put forward and so widely accepted that it is in danger of being canonized by sheer dint of repetition; 1 and thus one who would deny the essential validity of that notion bears the virtually insuperable burden of proof commonly accorded an accused heretic. Nevertheless, it will be argued here that natural law notions are attributed to the medieval English legislator with only the slightest support from the sources, and after only the most rudimentary and uncritical analyses of the implications of such an idea. -

Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett Rf Aser

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1919 Future Interests in Property in Minnesota Everett rF aser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Fraser, Everett, "Future Interests in Property in Minnesota" (1919). Minnesota Law Review. 1283. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW FUTURE INTERESTS IN PROPERTY IN MINNESOTA "ORIGINALLY the creation of future interests at law was greatly restricted, but now, either by the Statutes of Uses and of Wills, or by modern legislation, or by the gradual action of the courts, all restraints on the creation of future interests, except those arising from remoteness, have been done away. This practically reduces the law restricting the creation of future interests to the Rule against Perpetuities,"' Generally in common law jurisdictions today there is but one rule restricting the crea- tion of future interests, and that rule is uniform in its application to real property and to personal property, to legal and equitable interests therein, to interests created by way of trust, and to powers. In 1830 the New York Revised Statutes went into effect in New York state. The revision had been prepared by a commis- sion appointed for the purpose five years before. It contained a code of property law in which "the revisers undertook to re- write the whole law of future estates in land, uses and trusts .. -

Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1

Volume 21 Issue 1 1-1916 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1, 21 DICK. L. REV. 1 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol21/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dickinson Law Review VOL. XXI OCTOBER, 1916 No. 1 BUSINESS MANAGERS EDITORS John D. M. Royal, '17 Henry M. Bruner, '17 Lawrence D. Savige, '17 Edward H. Smith, '17 John H. Bonin, '17 William Lurio, '17 Joseph C. Paul, '18 Ethel Holderbaum, '18 Subscription $1.60 per annum, payable in advance WALLACE vs. EDWIN HARMSTAD, 44 PA. 492 In 1838 Arrison sold to four brothers Harmstad four adjoining lots, reserving out o2 each a yearly rent of !$60, payable half-yearly, in January and July. Each grantee, entered on his lot and built a house on it. The deeds were executed in duplicate each being signed by both parties. A part of the bargain was that the rents might be redeemed at any time. In the deeds was a blank with respect to the time of redemption, which was explained by Arrison as meaning that there was no limit of time. Some time after the delivery of the deeds, they were procured by Ar- rison for the alleged purpose of having them recorded, and while out of the possession of the Harmstads the blanks were filled with the words, "within ten years from the date thereof," making redemption after ten years impos- sible.