Primary Source 2.2 the RISE of FEUDAL SOCIETY in MEDIEVAL EUROPE (C. 9TH CENTURY)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LECTURE 5 the Origins of Feudalism

OUTLINE — LECTURE 5 The Origins of Feudalism A Brief Sketch of Political History from Clovis (d. 511) to Henry IV (d. 1106) 632 death of Mohammed The map above shows to the growth of the califate to roughly 750. The map above shows Europe and the East Roman Empire from 533 to roughly 600. – 2 – The map above shows the growth of Frankish power from 481 to 814. 486 – 511 Clovis, son of Merovich, king of the Franks 629 – 639 Dagobert, last effective Merovingian king of the Franks 680 – 714 Pepin of Heristal, mayor of the palace 714 – 741 Charles Martel, mayor (732(3), battle of Tours/Poitiers) 714 – 751 - 768 Pepin the Short, mayor then king 768 – 814 Charlemagne, king (emperor, 800 – 814) 814 – 840 Louis the Pious (emperor) – 3 – The map shows the Carolingian empire, the Byzantine empire, and the Califate in 814. – 4 – The map shows the breakup of the Carolingian empire from 843–888. West Middle East 840–77 Charles the Bald 840–55 Lothair, emp. 840–76 Louis the German 855–69 Lothair II – 5 – The map shows the routes of various Germanic invaders from 150 to 1066. Our focus here is on those in dark orange, whom Shepherd calls ‘Northmen: Danes and Normans’, popularly ‘Vikings’. – 6 – The map shows Europe and the Byzantine empire about the year 1000. France Germany 898–922 Charles the Simple 919–36 Henry the Fowler 936–62–73 Otto the Great, kg. emp. 973–83 Otto II 987–96 Hugh Capet 983–1002 Otto III 1002–1024 Henry II 996–1031 Robert II the Pious 1024–39 Conrad II 1031–1060 Henry I 1039–56 Henry III 1060–1108 Philip I 1056–1106 Henry IV – 7 – The map shows Europe and the Mediterranean lands in roughly the year 1097. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Sample Intercessions for Atonement & Healing

Diocese of Scranton Sample Intercessions for Atonement & Healing From the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions and the Diocese of Scranton Office for Parish Life It is recommended to include at least one of these intercessions in the Universal Prayer each weekend. 1. For the victims of abuse at the hands of some members of the clergy, may they find healing, support, and peace within the Catholic community, we pray to the Lord. 2. For the families of abuse victims, that their compassionate concern may affect healing and that their strong advocacy may bring about change within the Church and society, we pray to the Lord. 3. For Pope Francis, for the bishops of the United States, and all the bishops of the world, that they may heed the promptings of the Holy Spirit and work to promote justice for all victims of sexual abuse, we pray to the Lord. 4. That those terrorized by sexual abuse, especially those abused by priests of our Diocese, may find the courage to come forward to authorities and find the peace and consolation they need, we pray to the Lord. 5. That the Church may be a safe refuge for all in need, especially those who suffer physical, mental and sexual abuse, we pray to the Lord. 6. That all members of the Church may commit themselves to protect children and the most vulnerable in our communities, we pray to the Lord. 7. For all those in parishes and dioceses who are responsible for safe environment training programs which promote the protection of children, we pray to the Lord. -

Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History

SOME NOTES ON MANORS & MANORIAL HISTORY BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A.. D.Litt.. F.B.A..F.S.A. Some Notes on Manors & Manorial History By A. Hamilton Thompson, M.A., D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. The popular idea of a manor assumes that it is a fixed geo graphical area with definite boundaries, which belongs to a lord with certain rights over his tenants. In common usage, we speak of this or that lordship, almost in the same way in which we refer to a parish. It is very difficult, however, to give the word an exclusively geographical meaning. If we examine one of those documents which are known as Inquisitions post mortem, for example, we shall find that, at the death of a tenant who holds his property directly from the Crown, the king's escheator will make an extent, that is, a detailed valuation, of his manors. This will consist for the most part of a list of a number of holdings with names of the tenants, specifying the rent or other services due to the lord from each. These holdings will, it is true, be generally gathered together in one or more vills or townships, of which the manor may roughly be said to consist. But it will often be found that there are outlying holdings in other vills which owe service to a manor, the nucleus of which is at some distance. Thus the members of the manor of Rothley lay scattered at various distances from their centre, divided from it and from each other by other lordships. -

Feudalism Manors

effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their Recognizing own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and politi- Effects cal strength. What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and A New Social Order: Feudalism Muslim invasions In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the on medieval head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) Europe? River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landhold- ing, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C.until 256 B.C.Feudalism in Japan began in A.D.1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. -

Feudal Contract – Medieval Europe

FEUDAL CONTRACT – MEDIEVAL EUROPE Imagine you are living in Medieval Europe (500 – 1500). Despite the fact that a feudal contract is an unwritten contract, write out a feudal contract. You and a partner will take on the roles of lord and vassal: - You Need to Write Out the Contract: - The lord can have a certain title (i.e. duke/duchess, baron/baroness, or count/countess), and specify what social standing the vassal has (i.e. lower-level knight, peasant, etc.). - In your contract, specify how much acreage in land (fief) will be given to the vassal. - Specify how much military service the vassal will serve, and what kind of fighting they will do (i.e. cavalry, foot soldier…) - How much money will a vassal provide his lord if he is kidnapped, and if there is a ransom? How much will a vassal provide for one of the lord’s children’s weddings? (Specify money in terms of weight and precious metal such as “30 lbs. gold”). - Specify other duties from the readings (Feudalism HW and class handout) that will be done by a lord and vassal (i.e. the lord will give safety and will defend his vassal in court). - List any other duties a lord/vassal will do of your choosing. (i.e. farm a certain crop, make a certain craft) - Define feudalism, fief, knight, vassal, and serfs. - Sign and date your contract at the bottom to make it official, and make sure the date is between the year 500 and 1500. Example: Lord/Vassal Feudal Contract: I am a peasant (name of vassal) and will serve and be the vassal of (name of Lord/Duke). -

Farwell to Feudalism

Burke's Landed Gentry - The Kingdom in Scotland This pdf was generated from www.burkespeerage.com/articles/scotland/page14e.aspx FAREWELL TO FEUDALISM By David Sellar, Honorary Fellow, Faculty of Law, University of Edinburgh "The feudal system of land tenure, that is to say the entire system whereby land is held by a vassal on perpetual tenure from a superior is, on the appointed day, abolished". So runs the Sixth Act to be passed in the first term of the reconvened Scottish Parliament, The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000. The Act is welcome. By the end of the second millennium the feudal system had long outlived its usefulness, even as a legal construct, and had few, if any defenders. As the Scottish Law Commission commented in 1999, "The main reason for recommending the abolition of the feudal system of land tenure is that it has degenerated from a living system of land tenure with both good and bad features into some-thing which, in the case of many but not all superiors, is little more than an instrument for extracting money". The demise of feudalism brings to an end a story which began almost a thousand years ago, and which has involved all of Scotland's leading families. In England the advent of feudalism is often associated with the Norman Conquest of 1066. That Conquest certainly marked a new beginning in landownership which paved the way for the distinctive Anglo-Norman variety of feudalism. There was a sudden and virtually clean sweep of the major landowners. By the date of the Domesday Survey in 1086, only two major landowners of pre-Conquest vintage were left south of the River Tees holding their land direct of the crown: Thurkell of Arden (from whom the Arden family descend), and Colswein of Lincoln. -

![Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6001/notes-for-the-guidance-of-rep-dls-re-borough-observance-of-mourning-following-the-death-of-a-member-of-the-royal-family-not-including-the-sovereign-766001.webp)

Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]

Notes for the Guidance of Rep DLs re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [not including the Sovereign] The forms of Mourning are: NATIONAL MOURNING ROYAL MOURNING Following the death of a Member of The Royal Family, the Lord Chamberlain or the Earl Marshal will consult with the Prime Minister before seeking The Sovereign’s Commands with regard to mourning. No action should be taken until there is a formal announcement of the death (that is, when the media reports that Buckingham Palace or Downing Street has announced the death, not when they indicate that “reports are coming in of the death of …..”). National Mourning Observed by all, including national representatives serving abroad. Flags lowered from the day of death to the day of Funeral. Business/Sporting activities considered by Prime Minister’s Office. Royal Mourning Observed by Members of the Royal Family, Households of the Royal Family and Troops on Public Duties. Flags Flags should be flown at half-mast on the day the death is announced (or immediately following) and day of Funeral. Flags also lowered on any other occasions where Her Majesty has given special command. Half-mast means the flag is flown two-thirds of the way up the flagpole with at least the height of the flag between the top of the flag and the top of the flagpole. On flag poles that are more than 45o from the vertical, flags cannot be flown at half-mast and the pole should be left empty. When a flag is to be flown at half-mast it should first be raised all the way to the top of the mast, allowed to remain there for a second and then lowered to the half-mast position. -

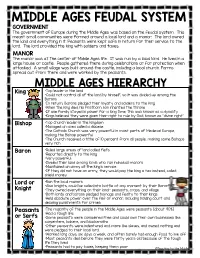

FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT the Government of Europe During the Middle Ages Was Based on the Feudal System

MIDDLE AGES FEUDAL SYSTEM GOVERNMENT The government of Europe during the Middle Ages was based on the feudal system. This meant small communities were formed around a local lord and a manor. The lord owned the land and everything in it. Peasants were kept safe in return for their service to the lord. The lord provided the king with soldiers and taxes. MANOR The manor was at the center of Middle Ages life. It was run by a local lord. He lived in a large house or castle. People gathered there during celebrations or for protection when attacked. A small village was built around the castle, including a local church. Farms spread out from there and were worked by the peasants. MIDDLE AGES HIERARCHY King *Top leader in the land *Could not control all of the land by himself, so it was divided up among the Barons *In return, Barons pledged their loyalty and soldiers to the king *When the king died, his firstborn son inherited the throne *If one family stayed in power for a long time, this was known as a dynasty *Kings believed they were given their right to rule by God, known as “divine right” Bishop *Top church leader in the kingdom *Managed an area called a diocese *The Catholic Church was very powerful in most parts of Medieval Europe, making the Bishop powerful *The Church received a tithe of 10 percent from all people, making some Bishops very rich Baron *Ruled large areas of land called fiefs *Reported directly to the king *Very powerful *Divided their land among lords who ran individual manors *Maintained an army at the king’s service *If -

Lift up Your Hearts. All: We Lift Them up to the Lord. Priest

Priest: The Lord be with you. CONGREGATION’S PRAYER CARD All: And with your spirit. NEW RESPONSES AT MASS Priest: Lift up your hearts. All: We lift them up to the Lord. (Changes are indicated in bold type.) Priest: Let us give thanks to the Lord our God. All: It is right and just. THE GREETING Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Holy, Holy, Holy Lord God of hosts. All: Amen. Heaven and earth are full of your glory. Priest: The Lord be with you. Hosanna in the highest. All: And with your spirit. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest. PENITENTIAL ACT A All: I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, Priest: The mystery of faith. that I have greatly sinned, in my thoughts and in my words, All: We proclaim your death, O Lord, and profess your in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, Resurrection until you come again. Striking your breast as you say: through my fault, Or When we eat this Bread and drink this Cup, through my fault, we proclaim your death, O Lord, until you come again. through my most grievous fault; therefore I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, Or Save us Saviour of the world, for by your Cross and all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, Resurrection, you have set us free. to pray for me to the Lord our God. -

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages After the collapse of Rome, Western Europe entered a period of political, social, and economic decline. From about 500 to 1000, invaders swept across the region, trade declined, towns emptied, and classical learning halted. For those reasons, this period in Europe is sometimes called the “Dark Ages.” However, Greco-Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions eventually blended, creating the medieval civilization. This period between ancient times and modern times – from about 500 to 1500 – is called the Middle Ages. The Frankish Kingdom The Germanic tribes that conquered parts of the Roman Empire included the Goths, Vandals, Saxons, and Franks. In 486, Clovis, king of the Franks, conquered the former Roman province of Gaul, which later became France. He ruled his land according to Frankish custom, but also preserved much of the Roman legacy by converting to Christianity. In the 600s, Islamic armies swept across North Africa and into Spain, threatening the Frankish kingdom and Christianity. At the battle of Tours in 732, Charles Martel led the Frankish army in a victory over Muslim forces, stopping them from invading France and pushing farther into Europe. This victory marked Spain as the furthest extent of Muslim civilization and strengthened the Frankish kingdom. Charlemagne After Charlemagne died in 814, his heirs battled for control of the In 786, the grandson of Charles Martel became king of the Franks. He briefly united Western empire, finally dividing it into Europe when he built an empire reaching across what is now France, Germany, and part of three regions with the Treaty of Italy. -

Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1

Volume 21 Issue 1 1-1916 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Dickinson Law Review - Volume 21, Issue 1, 21 DICK. L. REV. 1 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol21/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dickinson Law Review VOL. XXI OCTOBER, 1916 No. 1 BUSINESS MANAGERS EDITORS John D. M. Royal, '17 Henry M. Bruner, '17 Lawrence D. Savige, '17 Edward H. Smith, '17 John H. Bonin, '17 William Lurio, '17 Joseph C. Paul, '18 Ethel Holderbaum, '18 Subscription $1.60 per annum, payable in advance WALLACE vs. EDWIN HARMSTAD, 44 PA. 492 In 1838 Arrison sold to four brothers Harmstad four adjoining lots, reserving out o2 each a yearly rent of !$60, payable half-yearly, in January and July. Each grantee, entered on his lot and built a house on it. The deeds were executed in duplicate each being signed by both parties. A part of the bargain was that the rents might be redeemed at any time. In the deeds was a blank with respect to the time of redemption, which was explained by Arrison as meaning that there was no limit of time. Some time after the delivery of the deeds, they were procured by Ar- rison for the alleged purpose of having them recorded, and while out of the possession of the Harmstads the blanks were filled with the words, "within ten years from the date thereof," making redemption after ten years impos- sible.