The Copenhagen Test and Treat Hepatitis C in a Mobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyse Af Mulighederne for Automatisk S-Banedrift

Analyse af mulighederne for automatisk S-banedrift Indhold 1. Sammenfatning ....................................................................................... 5 2. Indledning ............................................................................................... 8 2.1. Baggrund og formål ......................................................................... 8 2.2. Udvikling og tendenser .................................................................. 10 2.3. Metode og analysens opbygning ..................................................... 11 2.4. Forudsætninger for OTM-trafikmodelberegningerne .................... 11 2.5. Øvrige forudsætninger ................................................................... 12 3. Beskrivelse af scenarier ......................................................................... 15 3.1. Basis 2025 ...................................................................................... 16 3.2. Klassisk med Signalprogram (scenarie 0) ...................................... 17 3.3. Klassisk med udvidet kørselsomfang (scenarie 1) ......................... 18 3.4. Klassisk med parvis sammenbinding på fingrene (scenarie 2) ..... 19 3.5. Metro-style (scenarie 3) ................................................................. 21 3.6. Metro-style med shuttle tog på Frederikssunds-fingeren (scenarie 4) .................................................................................... 23 3.7. Metro-style med shuttle tog på Høje Taastrup-fingeren (scenarie 5) ................................................................................... -

A. Transport-, Bygnings- Og Boligministeriet

Aktstykke nr. 81 Folketinget 2017-18 Afgjort den 12. oktober 2017 Tidligere fortroligt aktstykke D af 12. oktober 2017. Fortroligheden er ophævet ved ministerens skrivelse af den 22. marts 2018. 81 Transport-, Bygnings- og Boligministeriet. København, den 4. oktober 2017. a. Transport-, Bygnings- og Boligministeriet anmoder hermed om Finansudvalgets tilslutning til, at Ba- nedanmark igangsætter: – sporfornyelse af strækningen Valby – Frederikssund – fornyelse af perroner på Valby Station og – fornyelse af køreledningsanlægget mellem Valby Langgade og Vanløse. Projektets forventede totaludgift inkl. korrektionstillæg på 10 pct. udgør 535,7 mio. kr. i perioden 2017-19. Udgiften i 2017 på 40,1 mio. kr. afholdes af den på finansloven for 2017 på § 28.63.05. Banedanmark – fornyelse og vedligeholdelse af jernbanenettet opførte bevilling. Eksistensen af aktstykket er offentlig, mens indholdet er fortroligt af hensyn til statens forhandlings- position ved udbud af projektet. Aktstykkets fortrolighed ophæves efter kontraktindgåelse. b. Projektbeskrivelse Banedanmark har planlagt sporfornyelse af S-togstrækningen Valby-Frederikssund, inkl. begge stati- oner. I projektet fornyes også sideperronen ved spor 5 og Ø-perronen mellem spor 3 og 4 på Valby station. Endeligt fornyes køreledningsanlægget mellem Valby Langgade og Vanløse. Formålet med sidstnævnte del af projektet er en fornyelse af anlægget, så det funktionsmæssigt, sikkerhedsmæssigt og trafikalt lever op til nuværende standard. Hvis projektet ikke gennemføres, vil der være en øget risiko for hastighedsnedsættelser eller spærringer samt stigende vedligeholdelsesomkostninger på strækningen. Fornyelsesprojektet skal igangsættes som led i udmøntningen af Banedanmarks økonomiske ramme for fornyelse i perioden 2015-2020 på 9.038,2 mio. kr. (2013-priser), og Banedanmarks fornyelses- aktiviteter i 2018 er på finansloven for 2017 budgetteret til 1.445,0 mio. -

91 Yderste Stationer Afkortedes. Derved Mistede Passage- Rerne Fra Jægersborg, Gentofte Og Bernstorffsvej Myldre- Tidsbetjening

Hillerødtog er i 1964 på vej op ad stigningen nord for Holte Station. Et typisk Nordbanetog med S-maskine og en stribe CL- vogne med 2. klasse og til sidst en tilsvarende CLE med rejse- godsrum. Men første vogn er en 1. klasse sidegangsvogn litra AC, som var mere populære blandt de „fine“ kunder end „akvarierne“. (HGC) yderste stationer afkortedes. Derved mistede passage- modtaget. Benyttelsen i myldretidstogene var ganske god; rerne fra Jægersborg, Gentofte og Bernstorffsvej myldre- derimod kneb det mere i aftentimerne og weekenden. tidsbetjeningen, og i 1956 indførtes derfor en yderligere Nordbanens faste tog fik hermed den endelige, typiske myldretidslinje „B-ekstra“ (kun skiltet ”B”) mellem Lyngby sammensætning, nemlig i nordenden en 1. kl. vogn litra Et Hillerødtog på vej nordpå og København H med stop ved alle mellemstationer. AL, efterfulgt af et antal (normalt 5-6) CL-vogne og en passerer vandtårnet i Holte i På Nordbanen nord for Holte var det ikke kun week- kombineret person- og rejsegodsvogn litra CLE. I en række 1964. Gennem de store vinduer endtrafikken der voksede op gennem 1950‘erne, også af ekstratogene anvendtes dog 1.kl. vogne af sidegangs- i „akvariet“ kan man se hverdagstrafikken var stigende. I 1955 var der således på typen litra AC, ligesom en del af disse tog i lighed med „flystolenes“ hvide nakke- en hverdag i september godt 6000 rejsende til stationerne weekendtrafikkens ekstratog ikke medførte CLE-vogn. betræk. (HGC) Birkerød, Allerød og Hillerød, godt 100 % flere end i 1945. Siden sommeren 1955 havde man fået fast timedrift hele dagen på Nordbanens sydlige del, og antallet af ekstratog i myldretiden var oppe på tre, ja fra 1957 fire i den aktu- elle retning. -

TCRP Research Results Digest 77

May 2006 TRANSIT COOPERATIVE RESEARCH PROGRAM Sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration Subject Areas: IA Planning and Administration, VI Public Transit, VII Rail Responsible Senior Program Officer: Gwen Chisholm-Smith Research Results Digest 77 International Transit Studies Program Report on the Fall 2005 Mission INNOVATIVE TECHNIQUES IN THE PLANNING AND FINANCING OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS This TCRP digest summarizes the mission performed October 20– November 5, 2005, under TCRP Project J-3, “International Transit Studies Program.” This digest includes transportation information on the cities and facilities visited. This digest was prepared by staff of the Eno Transportation Foundation and is based on reports filed by the mission participants. INTERNATIONAL TRANSIT participants to learn from foreign experience STUDIES PROGRAM while expanding their network of domestic and international contacts for addressing The International Transit Studies Prog- public transport problems and issues. ram (ITSP) is part of the Transit Cooperative The program arranges for teams of pub- Research Program (TCRP). ITSP is managed lic transportation professionals to visit ex- by the Eno Transportation Foundation under emplary transit operations in other countries. contract to the National Academies. TCRP Each study mission focuses on a theme that was authorized by the Intermodal Surface encompasses issues of concern in public Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 and re- transportation. Cities and transit systems to authorized in 2005 by the Safe, Accountable, be visited are selected on the basis of their Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity ability to demonstrate new ideas or unique Act: A Legacy for Users. It is governed by approaches to handling public transportation a memorandum of agreement signed by the CONTENTS challenges reflected in the study mission’s National Academies, acting through its theme. -

Copenhagen Business School – Event Details

Copenhagen Business School – Event Details Date: Wednesday, 24 October, 2018 Time: Check-In/Registration: 4:30–5:00 p.m., Hall B, Solbjerg Plads Panel: 5:00–6:00 p.m., SPs05, Solbjerg Plads Recruitment Fair: 6:00–7:30 p.m., Hall B, Solbjerg Plads Location: Copenhagen Business School Solbjerg Plads 3 2000 Frederiksberg Web page with details and registration: http://www.career.cbs.dk/events/details.php?id=2403 Recommended hotels: SCANDIC Webers (★ ★ ★ ★) Vesterbrogade 11B, 1620 København V Phone: +45 33 31 14 32 https://www.scandichotels.dk/hoteller/danmark/kobenhavn/scandic-webers Ibsens Hotel (★ ★ ★) Vendersgade 23, 1363 København K Phone: 33 45 77 44 http://www.arthurhotels.dk/dk/ibsens-hotel/ Hotel CABINN Scandinavia (★ ★) Vodroffsvej 55, 1900 Frederiksberg C Phone: +45 35 36 11 11 https://www.cabinn.com/en/hotel/cabinn-scandinavia-hotel Transportation: Airport Copenhagen Airport (CPH) Airport to hotel Copenhagen Airport (CPH) is eight kilometers southeast of the city. By Metro, it takes less than 15 minutes to get to the city center and 20 minutes to get to CBS. Remember to buy a ticket before boarding the train. Tickets are available from the DSB ticket office above the railway station in Terminal 3 and at ticket machines on the platform. The price for a one-way ticket is approx. DKK 30. Taxis are also available (approx. fare from the airport to Frederiksberg is DKK 350). DocNet – Copenhagen Business School Page 2 of 2 Hotel to school The easiest way to get to CBS, from almost anywhere in the Copenhagen area, is by taking the Metro line M2 towards Vanløse. -

From Copenhagen Central Station by Bus • Address: 22 Nyhavn, 1051 København • Tel

Welcome at thinkstep! 1 Hotels in Copenhagen 1. Hotel Bethel 2. Hotel Maritime 3. Admiral Hotel 4. Danhostel Copenhagen City 5. Radisson Blu 2 Hotel Bethel • Location: Situated approx.1 km from the Royal Danish Library (10/15 minute walk along the water), about 20 minutes away from Copenhagen airport by either metro or car, about 15 minutes away from Copenhagen Central Station by bus • Address: 22 Nyhavn, 1051 København • Tel. number: +45 33 13 03 70 • Cost of single room: from 895 DKK per night • Website: http://www.hotel-bethel.dk/index.php/en/ • Directions: • From the airport by car: Take Ellehammersvej to E20. Continue on E20 to København S. Take exit 20- København C from E20. Continue on Sjællandsbroen to København SV. Continue onto Vabsygade/O2. Turn right onto Holbergsgade and then follow the street until Nyhavn. Then turn left onto Nyhavn. • From the airport by metro: Take the line M2 in direction of Vanløse and get off at Kongens Nytorv. • • From Copenhagen Central Station: Leave the platform not at the exist in the main central station building, but on the other side of the platform. The bus stop is situated on a bridge that crosses the train rails and is called Hovedbanegården (Tietgensgade). Take the bus 1A in the direction of Hellerup St. or Klampenborg St. and get off at Kongens Nytorv. • • From Kongens Nytorv to hotel: Cross the O2 street and pass by Det Kongelige Teater (Royal Danish Theater). Then turn right onto Nyhavn. The hotel is on your right side. 3 Hotel Bethel 4 Hotel Maritime • Location: Situated approx. -

Rail Transit Capacity

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 3 RAIL TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. RAIL CAPACITY BASICS ..................................................................................... 3-1 Introduction................................................................................................................. 3-1 Grouping ..................................................................................................................... 3-1 The Basics................................................................................................................... 3-2 Design versus Achievable Capacity ............................................................................ 3-3 Service Headway..................................................................................................... 3-4 Line Capacity .......................................................................................................... 3-5 Train Control Throughput....................................................................................... 3-5 Commuter Rail Throughput .................................................................................... 3-6 Station Dwells ......................................................................................................... 3-6 Train/Car Capacity...................................................................................................... 3-7 Introduction............................................................................................................. 3-7 Car Capacity........................................................................................................... -

The Cityring Ties the City Together

FACTS: The Cityring ties the city together Only a few years after the opening of the existing Metro in 2002, the preparations for The Cityring began, and in 2007 a law was passed. The capital grows by approximately 10,000 inhabitants each year and therefore the need to find transport solutions for the city’s inhabitants, employees and the guests increases. A metro removes the traffic from streets and alleys. With its 17 new stations, The Cityring will transform the capital. In part as many new urban spaces are created around the stations, but primarily because of how the city is tied together. It is expect- ed that next year Cityringen will double the number of metro passengers from approximately 65 to 122 million annually. Thus, stations with access to the metro will Amount of passengers expected in the Metro in millions become new traffic hubs in Copenhagen and Frederiksberg. Photo: Ulrik Jantzen Faster across the city Travel time examples of Line M3 The Cityring (M3) means a comprehensive up- Copenhagen Central St. - grade of the existing metro network in Copenha- Frederiksberg: 5 minutes gen which up until now has consisted of 22 Sta- tions. City Hall Square – In the future, it will be both easier and much fa- Trianglen: 7 minutes ster to get around the city. With an average Nørrebros Runddel – speed of approximately 40 km/h, a ride with The Copenhagen Central St.: 8 minutes Cityring takes 24 minutes. However, as the me- tro trains run in both directions, the timewise Vibenshus Runddel – longest ride between, for example, Copenhagen Enghave Plads: 11 minutes and Skjolds Plads will only take 12 minutes Several easy interchanges with the Metro The Cityring’s 15.5 kilometres long underground tunnels connect Indre By, Østerbro, Nørrebro, Vest- erbro, and Frederiksberg. -

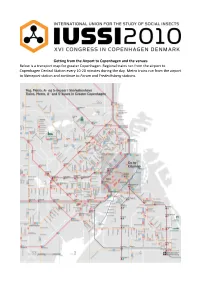

Getting from the Airport to Copenhagen and the Venues Below Is a Transport Map for Greater Copenhagen

Getting from the Airport to Copenhagen and the venues Below is a transport map for greater Copenhagen. Regional trains run from the airport to Copenhagen Central Station every 10-20 minutes during the day. Metro trains run from the airport to Nørreport station and continue to Forum and Frederiksberg stations. How to find your hotel or hostel, and get from there to the venues Central Copenhagen All of the hotels below are close to the centre of Copenhagen, and within walking distance of Copenhagen Main Station and the Imperial Cinema. DanHostel Copenhagen H. C. Andersens Boulevard 50, DK-1553 Copenhagen V, Tel. 33118585 Close to Langebro bridge, ca. 15 minutes walk from Copenhagen Main Station. To get to the Panum institute, walk to the town hall square and take bus 6A. Grand Hotel Vesterbrogade 9, DK-1620 København, Tel. 33156690 4 minutes walk from Copenhagen Main Station. Bus 6A runs from near the hotel to the Panum Institute. Hotel Danmark Vester Voldgade 89, DK-1552 Copenhagen K, Tel. 33114806 Close to the town hall and Tivoli, about 10 minutes walk from Copenhagen Main Station. Bus 6A runs from the town hall square to the Panum Institute. Imperial Hotel Vester Farimagsgade 9, DK-1606 Copenhagen V, Tel. 33128000 Next to Vesterport S-station, 6 minutes walk from Copenhagen Main Station. Bus 6A runs from Vesterport station to the Panum Institute. Norlandia Mercur Hotel Vester Farimagsgade 17, DK-1606 Copenhagen V, Tel. 33125711 2 minutes walk from Vesterport S-station, 8 minutes walk from Copenhagen Main Station. Bus 6A runs from Vesterport station to the Panum Institute. -

Annual Report 2019 Metroselskabet I/S

Metroselskabet I/S Annual Report Report Annual 2019 Annual Report 2019 Metroselskabet I/S Annual Report 2019 Contents Contents Foreword 4 Key Figures 7 2019 in Brief 8 Directors’ Report 10 Finances 13 Operation and Maintenance 24 Construction 32 Business Development 46 About Metroselskabet 48 Ownership 50 Board of Directors of Metroselskabet 52 Executive Management of Metroselskabet 55 Metroselskabet's Employees 56 Compliance Testing of Metroselskabet 57 Annual Accounts 58 Accounting Policies 60 Accounts 65 Management Endorsement 94 Independent Auditors’ Report 96 Appendix to the Directors’ Report 100 Long-Term Budget 102 3 Annual Report 2019 Foreword Foreword Metroselskabet’s result for 2019 before per cent. The company’s financial perfor- depreciation and write-downs is mance in 2019 thus exceeded expectations, significantly higher than expected and the result is assessed to be satisfactory. The result for 2019 before depreciation and write-downs is a profit of DKK 436 million, Continued increase in Metro which is DKK 164 million higher than ex- passenger numbers pected. The increase is primarily attribut- 78.8 million passengers took the Metro in able to higher passenger revenue due to 2019. This is an increase of around 22 per more customers than expected using the cent compared to last year, when 64.7 mil- Metro in 2019, as well as a higher fare per lion passengers took the Metro. Much of passenger than expected. The high passen- the growth in passenger numbers can be at- ger numbers mean that, for the first time tributed to the opening of the new M3 Cit- in its history, Metroselskabet achieved fare yring Metro line in September 2019. -

Copenhagen and Its Region

TECHNICAL NOTE NO. 9 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF TRANSPORT POLICY PROCESSES COPENHAGEN AND ITS REGION CREATE PROJECT Congestion Reduction in Europe, Advancing Transport Efficiency TECHNICAL NOTE PREPARED BY: Charlotte Halpern & Caterina Orlandi Sciences Po, Centre d’études européennes et de politique comparée (CEE), CNRS, Paris, France CREATE has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 636573 Comparative Analysis of Transport Policy Processes - Copenhagen and its region 1 // 9 THE CREATE PROJECT IN BRIEF Transport and mobility issues have increased in relevance on political agendas in parallel with the growing share of EU population living in cities, urban sprawl and climate change. In view of the negative effects of car use, there is a renewed interest about the role that transport should play in the sustainable city. The CREATE project explores the Transport Policy Evolution Cycle. This model is a useful starting point for understanding how this evolution took place, and the lessons that we can learn for the future. Within the CREATE project, the study coordinated by the Sciences Po, CEE team (WP4) explores the historical evolution of transport policies and processes – from ‘car-oriented’ to ‘planning for city life’ – in five European cities (Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Paris, Vienna). Paying attention to case-specific contextual factors, policy instruments and programmes and involved stakeholders, this comparative analysis unveils the processes and the main drivers for change. This technical note concerns Copenhagen and its region. DID YOU KNOW? COPENHAGEN'S TRANSPORT SUMMARY FINDINGS NETWORK IS: ROADS Copenhagen is considered to be a ‘gold standard’ example ROAD NETWORK 1.020 km of the liveable city. -

Forecasts: Fact Or Fiction? Uncertainty and Inaccuracy in Transport Project Evaluation Nicolaisen, Morten Skou

Aalborg Universitet Forecasts: Fact or Fiction? Uncertainty and Inaccuracy in Transport Project Evaluation Nicolaisen, Morten Skou Publication date: 2012 Document Version Accepted author manuscript, peer reviewed version Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Nicolaisen, M. S. (2012). Forecasts: Fact or Fiction? Uncertainty and Inaccuracy in Transport Project Evaluation. Department of Develpment and Planning, Aalborg University. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: December 25, 2020 Forecasts: Fact or Fiction? Uncertainty and Inaccuracy in Transport Project Evaluation Ph.D. Thesis by Morten Skou Nicolaisen Department of Development and Planning - Aalborg University December 2012 Til mine forældre Forecasts: