A Case for Efficient Legal and Institutional Frameworks for Cross-Border Railway Development in the East African Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region

Technical Report: Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region Larry Phipps, Short-term Consultant Submitted by: AECOM Submitted to: USAID/Southern Africa Gaborone, Botswana March 2009 USAID Contract No. 690-M-00-04-00309-00 (GS 10F-0277P) P.O. Box 602090 ▲Unit 4, Lot 40 ▲ Gaborone Commerce Park ▲ Gaborone, Botswana ▲ Phone (267) 390 0884 ▲ Fax (267) 390 1027 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 4 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Objectives of Study .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Report Structure................................................................................................. 10 3. BEITBRIDGE BULAWAYO RAILWAY CONCESSION ............................................. 11 3.1 Objectives of Privatization .................................................................................. 11 3.2 Scope of Railway Privatization ........................................................................... 11 3.3 Mode of Privatization......................................................................................... -

Railways: Looking for Traffi C

Chapter11 Railways: Looking for Traffi c frican railroads have changed greatly stock. Moreover, various confl icts and wars in the past 30 years. Back in the 1980s, have rendered several rail sections unusable. A many railway systems carried a large As a result, some networks have closed and share of their country’s traffi c because road many others are in relatively poor condition, transport was poor or faced restrictive regu- with investment backlogs stretching back over lations, and rail customers were established many years. businesses locked into rail either through Few railways are able to generate signifi - physical connections or (if they were para- cant funds for investment. Other than for statals) through policies requiring them to use purely mineral lines, investment has usually a fellow parastatal. Since then, most national come from bilateral and multilateral donors. economies and national railways have been Almost all remaining passenger services fail liberalized. Coupled with the general improve- to cover their costs, and freight service tariffs ment in road infrastructure, liberalization has are constrained by road competition. More- led to strong intermodal competition. Today, over, as long as the railways are government few railways outside South Africa, other than operated, bureaucratic constraints and lack dedicated mineral lines, are essential to the of commercial incentives will prevent them functioning of the economy. from competing successfully. Since 1993, sev- Rail networks in Africa are disconnected, eral governments in Africa have responded by and many are in poor condition. Although concessioning their systems, often accompa- an extensive system based in southern Africa nied by a rehabilitation program funded by reaches as far as the Democratic Republic of international fi nancial institutions. -

Port of Maputo, Mozambique

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Transport Evolution presents 13 - 14 May 2019 | Port of Maputo, Mozambique 25+ expert speakers, including: Osório Lucas Chief Executive Officer, Maputo Port Development Company Col. Andre Ciseau Secretary General, Port Management Association of Eastern & Southern Africa (PMAESA) Clive Smith Chief Executive Officer, Walvis Bay Corridor Group, Namibia Johny Smith Chief Executive Officer, TransNamib Holdings Limited, Namibia Boineelo Shubane Director Operations, Botswana Railways, Botswana Building the next generation of ports and rail in Mozambique Host Port Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: Simultaneous conference translation in English and Portuguese will be provided Será disponibilizada tradução simultânea da conferência em Inglês e Português www.transportevolutionmz.com Welcome to the inaugural Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution Forum Ports and railways are leading economic engines for Mozambique, providing access to import and export markets, driving local job creation, and unlocking opportunities for the development of the local blue economy. Hosted by Maputo Port Development Company, Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution prepares the region’s ports and railways for the fourth industrial revolution. Day one of the extensive two-day conference will feature a high level keynote comprising of leading African ports and rail authorities and focus on advancing Intra-African trade. We then explore challenges, opportunities and solutions for improving regional integration and connectivity. Concluding the day, attendees will learn from local and international ports authorities and terminal operators about challenges and opportunities for ports development. Day two begins by looking at major commodities that are driving infrastructure development forward and what types of funding and investment opportunities are available. This is followed by a rail spotlight session where we will learn from local and international rail authorities and operators about maintenance and development projects. -

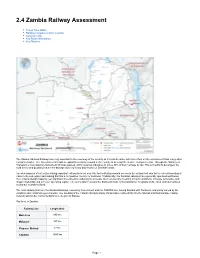

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment Travel Time Matrix Railway Companies and Consortia Capacity Table Key Route Information Key Stations The Zambia National Railways are very important to the economy of the country as it is a bulk carrier with less effect on the environment than many other transport modes. The Government intends to expand its railway network in the country to develop the surface transport sector. Through the Ministry of Transport, a new statutory instrument (SI) was passed, which requires industries to move 30% of their carriage by rail. This is in a bid to decongest the road sector and possibly reduce the damage done by heavy duty trucks on Zambian roads. The development of rail routes linking important exit points is not only vital for facilitating smooth access to the outside but also for the overall boosting of trade in the sub-region and making Zambia a competitive country for business. Traditionally, the Zambian railways have generally operated well below their original design capacity, yet significant investment is underway to increase their volumes by investing in track conditions, increase locomotive and wagon availability and increase operating capital. The rail network remains the dominant mode of transportation for goods on the local and international routes but is under-utilized. The main railway lines are the Zambia Railways, owned by Government and the TAZARA line, linking Zambia with Tanzania, and jointly owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments. The opening of the Chipata-Mchinji railway link provides connectivity into the Malawi and Mozambique railway network and further connects Zambia to the port of Nacala. -

National Transportation System in the Republic of Zambia

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1990 National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia Febby Mtonga WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Mtonga, Febby, "National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia" (1990). World Maritime University Dissertations. 877. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/877 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non- commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WMU LIBRARY WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo ~ Sweden THE NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA by Febby Mtonga Zambia A paper submitted to the faculty of the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE in GENERAL MARITIME ADMINISTRATION The views and contents expressed in this paper reflect entirely those of my own and are not to be construed as necessarily endorsed by the University Signed: Date : 0 5 I 11 j S O Assessed by: Professor J. Mlynarcz] World Maritime University Ilf Co-assessed by: U. 2).i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ii ABBREVIATIONS ... LIST OF MAPS AND APPENDICES iv CHAPTER 1 M • O • o Profile of the Republic of Zambia 1 1.1.0 Geographical Location of Zambia 1.2.0 Population 1.3.0 The Economy 1.3.1 Mining 1.3.2 Agriculture 3 1.3.3 Manufacturing 4 1.3.4 Transportation 7 1. -

ZAMBIA RAILWAYS LIMTED Zambia As a Link of Africa Through Rail

ZAMBIA RAILWAYS LIMTED Zambia as a link of Africa through Rail TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Brief about Zambia Railways Limited (ZRL) 2. ZRL Regional and Port linkages 3. Greenfield Regional and Port linkages 4. Trade Facilitation 5. Challenges being faced by railways in Africa 6. Possible solutions to Africa’s railway challenges 7. ZRL investment needs 8. Conclusion Brief about ZRL . ZRL is a parastatal railway organization under the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), mandated to operate both freight and passenger trains. The company is headquartered in Kabwe, Central Province. The main workshops and the CTC are also in Kabwe. Strategic Vision: To be the preferred regional railway transport and logistics provider Strategic Mission: To provide sustainable and competitive rail transport and logistics solutions to customers and deliver shareholder value ZRL Regional and Port linkages Zambia is linked to almost all the trade corridors. Land linked (road and rail) to eight neighbors and beyond the country’s borders. We are a hub. The main trade corridors for Zambia by rail include: .The North-South Corridor .The Dar-es-Salaam Corridor .The Nacala Corridor .The Beira Corridor .Coming up is the Kazungula corridor Shortest route from Ndola is Dar-es-Salaam – 1,976km The longest route is Ndola-Durban – 2,951km. Greenfield regional and Port linkages Livingstone – Kazungula – Mosetse (about 440km). This will reduce transit time by about 12 days on the corridor – one stop border effect. Petauke to Beira (960km) - to connect to Mozambique; Kafue to Lions den - will reduce the distance by rail to South Africa and Mozambique ports by about 1,000km. -

A Situational Study of Rail Transport Usage in Zambia

Journal of Business Administration and Management Sciences Research Vol. 5(6), pp. 077-088, December, 2016 Available online athttp://www.apexjournal.org ISSN 2315-8727© 2016 Apex Journal International Full Length Research A situational study of rail transport usage in Zambia Fred Mwila1* and Erastus M. Mwanaumo2 1 Post Graduate Student, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia. 2Lecturer, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia; P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia. Accepted 19 September, 2016; Published 5 December, 2016 Rail transport is critical for the development of any country. This is especially so for Zambia which is land locked. With its inherent advantage of being bulk carrier, safer and cheaper, rail transport is an important cog in intermodal transportation of goods and services. It is also more environmentally friendly, has less congestion and is more fuel efficient than other transport modes. A poorly utilised railway adversely affects overall national transport system and leads to low output which results in decreased contribution to the country’s economy. In some countries, especially the developed ones, freight and passenger rail traffic has been on the increase. However the opposite is the case in Zambia where railway traffic has continued to deteriorate. This paper seeks is to establish the position of railways in the Zambian transport system and propose ways of addressing causal factors and it is based on findings from research on ‘a comparative study of access to railways in Zambia relative to road transport’. Results indicate that railways carried a partly eight percent (8.0%) of the cargo transported by the road and rail in 2015. -

Transport Evolution Mozambique Forum & Showcase

SALES BROCHURE TRANSPORT EVOLUTION MOZAMBIQUE FORUM & SHOWCASE 13 – 15 APRIL 2021 PORT OF MAPUTO, MOZAMBIQUE Host Port Authority: Host Rail Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: www.transportevolutionmz.com EVENT OVERVIEW Transport Evolution Mozambique Forum & Showcase takes place in Maputo in April 2021. The event falls part of dmg events’ Transport Evolution series, making it a well- known and trusted brand. Furthermore, the event has the full support of Mozambique’s Minister of Transport and Communication, Maputo Port Development Company and CFM (Mozambique’s rail authority). We will once again bring together leaders from the regional and international transport community to accelerate new business opportunities in the port, rail and road sectors. The forum features sought-after industry experts to discuss strategic and technical topics. It also plays host to the public and private sector as they identify opportunities and implement plans to upgrade and maintain existing transport infrastructure, as well as develop new systems to improve service delivery. WHAT TO EXPECT IN 2021: 800+ 2 150+ Total attendees Day conference High-level conference delegates 15+ NEW SITE VISIT Port, rail & road authorities B2B exhibition Tour of Port of Maputo THOUGHT-LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE The comprehensive programme will address the full range of opportunities and challenges now facing the industry, equipping delegates to make informed strategic and operational decisions over the coming year. To learn more contact Kelly Easton: E: [email protected] T: +27 21 700 5508 www.transportevolutionmz.com 2019 OVERVIEW Minister of Transport and Communications, Hon. Carlos Mesquita delivered a keynote address where he revealed government is preparing a preliminary new Ports Law aimed at increasing the operational efficiency of the national port system by attracting investments and removing obstacles hampering the exploitation of existing capacity. -

Analysis of Zambia Railway Sector – Structural Deficiencies & the Way Forward

Source: hhttps://www.dailynation.info/zrl-gets-850m-fillip/ Source: ANALYSIS OF ZAMBIA RAILWAY SECTOR – STRUCTURAL DEFICIENCIES & THE WAY FORWARD ANALYSIS OF ZAMBIAANALYSIS RAILWAY SECTOR – STRUCTURAL DEFICIENCIES & THE WAY FORWARDJune | 20191 PREPARED BY: TABLE OF CONTENTS RESEARCH: Albert Kasoma (Senior Researcher) with the support of Bernadette Deka Zulu (Executive Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Director) Introduction 6 TECHNICAL REVIEW: Brief History of Rail Transport in Zambia 9 Chileshe Chaunga (Senior Researcher) Zambian Railways Limited. 11 TAZARA 12 EDITORIAL TEAM: Key Challenges with Railway Transport in Zambia 17 Brian Sambo Mwila (Communication Specialist) Layout and Design Melody M. Simukali (Head Communications and Grants) Editorial Market share 19 Government Interventions to Increase Rail Freight 20 Lessons from Other Countries -Railways Models in Africa 21 Way forward; Structural and Management Systems to make the Rail Sector Profitable 24 Creation of the Railway Development 25 Decentralisation 25 Private Participation 26 Service Contracts 26 Infrastructure Construction and Maintenance 26 Equipment Ownership and Leasing 27 Management Contracts 28 Private Operations of Trains 29 Full Private Ownership 29 Public-Private Partnership 30 Conclusion 31 Recommendations 32 References 34 This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by the laws of The Republic of Zambia. This electronic representation of PMRC intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of PMRC electronic documents to a non-PMRC website is prohibited. PMRC electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from PMRC to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see PMRC Permissions . -

A Situational Analysis of Transport Usage in Zambia: a Modal Perspective of Railway Freight Services from 1960’S to 2018

Proceedings of the 2nd African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Harare, Zimbabwe, December 7-10, 2020 A situational Analysis of Transport Usage in Zambia: A Modal Perspective of Railway Freight Services from 1960’s to 2018 Chikusela Sikazwe1, 1Graduate School of Business, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia [email protected], Erastus Mishengu Mwanaumo2 2Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Great East Road, Lusaka, Zambia [email protected] Mwewa Mambwe3 3Department of Construction Management and Quantity Surveying, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] Richard Kasongo Mwale1 1Graduate School of Business, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Zambia’s transportation policy highlights gaps in the transportation sector. This review focuses on analysing railway freight services and provides a departure from other similar reviews through a critical review of the Zambia railway sector gaps. The study sought to review existing literature, reports, and online information sources on Zambia railway freight services by grouping challenges into thematic groups. Causal loop analysis is used to identify cause and effect relationships among challenges specific to Zambia. Findings indicate that Zambia’s railroad infrastructure quality score (2.4) benchmarks below the average mean score (3.5) of all countries in 2017 and further benchmarks below the income group ‘eight-year average’ mean scores on infrastructure quality and train efficiency. Zambia has been recording declining railway volumes in terms of ton-km over a 37-years period. Five main thematic areas are identified as the main challenges for the railway sector in Zambia. -

Zambia Railways and the Economic Development Of

ZAMBIA RAILWAYS AND THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF ZAMBIA, 1967-1991 BY BEATRICE KAPANDA A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Zambia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History THE UNIVERSITY OF ZAMBIA LUSAKA 2017 DECLARATION I, BEATRICE KAPANDA, do declare that this dissertation was solely composed and written by me. Sources of information have been adequately acknowledged. This dissertation has not been submitted for a degree at the University of Zambia or any another university. Signed………………………………… Date…………………………………… i COPYRIGHT All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation maybe reproduced or stored in any form or by any means without prior permission from the author or the University of Zambia. ii APPROVAL This dissertation by Beatrice Kapanda is approved as fulfilling the requirement for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in History by the University of Zambia. EXAMINERS NAME SIGNATURE DATE 1.………………………………… ………………………. ……………………... 2………………………………… …………………….…. …………………….. 3………………………………… ……………………….. ..……………………. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to the memory of my dear late parents, Morgan Nonde Kapanda and Selita Mulenga Kapanda who never lived long to see my achievements in my education. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I give glory to God for my life and strength to work on this study. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Mr. Friday E. Mulenga whose valuable advice, comments and suggestions made it possible for me to write this dissertation. My thanks go to my dear husband, Kelvin Simataa and my daughters, Dorothy, Chomba, Nasilele, Nalukena and my nephew Alex, who really knew what it felt like to be on their own. -

LTPF Chapter 7 Africa Transport Infrastructure Planning.Pdf

CHAPTER 7 AFRICA TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING AFRICA TABLE OF TRANSPORT CONTENTS INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING AFRICA TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING 1. INTRODUCTION 419 2. OVERVIEW OF DEMAND 419 2.1 TOTAL FREIGHT SURFACE FLOWS (SADC COUNTRIES) 419 2.1.1 SOUTH AFRICA CROSS BORDER TRAFFIC (TRANSNET TRANSPORTATION MODEL) 419 2.1.2 SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA TOTAL ROAD AND RAIL FLOWS 421 2.1.3 CRUDE OIL PIPELINE FLOWS 429 2.2 PORTS (ALL MAJOR AFRICAN PORTS) 432 2. OVERVIEW OF CONDITION AND CAPACITY STATUS QUO 434 2.1 RAIL 434 2.2 PORTS 439 2.3 PIPELINES 442 3. OVERVIEW OF REGIONAL CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES 444 3.1 KEY ISSUES AND TRENDS HAMPERING DEVELOPMENT 444 3.2 LESSONS LEARNED 445 3.3 OVERVIEW OF SADC CORRIDORS 446 3.3.1 SALIENT ISSUES NEGATIVELY IMPACTING ON CORRIDOR OPERATIONS 454 3.4 CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENTS AND PLANS 455 3.4 FORECASTED REGIONAL DEMAND 457 3.6 STRATEGIC RAIL PROJECTS 458 3.7 FOCUS AREAS 459 3.8 STRATEGIC PORT PROJECTS 470 3.9 MAJOR PORT PROJECTS 471 3.10 STRATEGIC PIPELINE PROJECTS 475 3.11 MAJOR PIPELINE PROJECTS 476 4. TRANSNET STRATEGIES AND DEVELOPMENT PLANS 477 4.1 STRATEGY 477 Please note this Long-Term Framework Plan is not a business or operational plan, and is unconstrained to capital planning and independent to other more detailed Transnet business and operating division (OD) plans. The LTPF is only a planning tool, to guide Transnet and all external and public stakeholders. The LTPF is published annually at www.transnet.net. Transnet SOC Ltd © LTPF 2016 417 AFRICA ACRONYMS TRANSPORT AND ABBREVIATIONS INFRASTRUCTURE