UNCTAD/LDC/115 20 July 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region

Technical Report: Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region Larry Phipps, Short-term Consultant Submitted by: AECOM Submitted to: USAID/Southern Africa Gaborone, Botswana March 2009 USAID Contract No. 690-M-00-04-00309-00 (GS 10F-0277P) P.O. Box 602090 ▲Unit 4, Lot 40 ▲ Gaborone Commerce Park ▲ Gaborone, Botswana ▲ Phone (267) 390 0884 ▲ Fax (267) 390 1027 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 4 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Objectives of Study .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Report Structure................................................................................................. 10 3. BEITBRIDGE BULAWAYO RAILWAY CONCESSION ............................................. 11 3.1 Objectives of Privatization .................................................................................. 11 3.2 Scope of Railway Privatization ........................................................................... 11 3.3 Mode of Privatization......................................................................................... -

Socio-Economic Baseline Survey of Villages Adjacent to the Vidunda Catchment Area, Bordering Udzungwa Mountains National Park

Socio-Economic Baseline Survey of Villages Adjacent to the Vidunda Catchment Area, Bordering Udzungwa Mountains National Park Incorporating a Socio-Economic Monitoring Plan for 29 Villages North and East of the Udzungwa Mountains National Park Paul Harrison November 2006 WORLD WIDE FUND FOR NATURE TANZANIA PROGRAMME OFFICE (WWF-TPO) WITH SUPPORT FROM WWF NORWAY AND NORAD Socio-Economic Baseline Survey of Villages Adjacent to the Vidunda Catchment Area, Bordering Udzungwa Mountains National Park Report compiled by Paul Harrison, Kilimanyika Produced on behalf of WWF Tanzania Programme Office, P. O. Box 63117, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Co-Financed by NORAD and WWF Norway All photographs © Kilimanyika, unless otherwise stated. A series of photographs accompanying this report may be obtained by contacting Kilimanyika The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of WWF Tanzania, WWF Norway or NORAD. Bankipore House High Street Brill, Bucks HP18 9ST, UK Tel. +44 7739 803 704 Email: [email protected] Web: www.kilimanyika.com 2 Paul Harrison/Kilimanyika for WWF Tanzania Table of Contents Tables and Figures..............................................................................................................................................4 Abbreviations and Acronyms .............................................................................................................................5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................6 -

Railways: Looking for Traffi C

Chapter11 Railways: Looking for Traffi c frican railroads have changed greatly stock. Moreover, various confl icts and wars in the past 30 years. Back in the 1980s, have rendered several rail sections unusable. A many railway systems carried a large As a result, some networks have closed and share of their country’s traffi c because road many others are in relatively poor condition, transport was poor or faced restrictive regu- with investment backlogs stretching back over lations, and rail customers were established many years. businesses locked into rail either through Few railways are able to generate signifi - physical connections or (if they were para- cant funds for investment. Other than for statals) through policies requiring them to use purely mineral lines, investment has usually a fellow parastatal. Since then, most national come from bilateral and multilateral donors. economies and national railways have been Almost all remaining passenger services fail liberalized. Coupled with the general improve- to cover their costs, and freight service tariffs ment in road infrastructure, liberalization has are constrained by road competition. More- led to strong intermodal competition. Today, over, as long as the railways are government few railways outside South Africa, other than operated, bureaucratic constraints and lack dedicated mineral lines, are essential to the of commercial incentives will prevent them functioning of the economy. from competing successfully. Since 1993, sev- Rail networks in Africa are disconnected, eral governments in Africa have responded by and many are in poor condition. Although concessioning their systems, often accompa- an extensive system based in southern Africa nied by a rehabilitation program funded by reaches as far as the Democratic Republic of international fi nancial institutions. -

Tender Advert -Tc 1015-19/20

BOTSWANA RAILWAYS PUBLIC TENDER NOTICE ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANTS FOR THE EVALUATION OF BIDS FOR THE CONSULTANCY SERVICES TO CONDUCT A BANKABLE FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE TWO RAIL LINKS OF MOSETSE-KAZUNGULA-LIVINGSTONE AND MMAMABULA LEPHALALE-TC 1015-19/20 Telex or facsimile tender submissions will not be The Procuring Entity is Botswana Railways and considered. Zambia Railways Limited. One (1) original tender document marked Botswana Railways (BR) is a Government Enterprise ORIGINAL and Four (4) duplicate copies of the given a mandate as sole Rail operator since original Document marked copy in one sealed establishment in 1987 (BR Act 1986; Amended in envelope clearly marked: “Tender Reference No. 2004). The act was amended to allow BR to form TC 1015 19/20 ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANTS FOR Joint Ventures, Subsidiary companies and to THE EVALUATION OF BIDS FOR THE CONSULTANCY exploit other business opportunities. SERVICES TO CONDUCT A BANKABLE FEASIBILITY BR is mandated to provide transportation of goods STUDY FOR THE TWO RAIL LINKS OF MOSETSE- and passengers within Botswana, effi ciently, safely KAZUNGULA-LIVINGSTONE AND MMAMABULA- and cost-effectively, along sound commercial LEPHALALE” shall be delivered to: lines. The Supply Chain Manager Botswana Railways Zambia Railways Limited (ZRL) is a parastatal Head Quarters railway of Zambia mandated to operate both Along A1 Road passenger and freight trains by an Act of Parliament Mowana Ward Mahalapye, Botswana with company registration number 12780. It is a The name and address of the bidder should be public company with the Industrial Development clearly marked on the envelope. Corporation (IDC) as its sole shareholder. -

Results of Railway Privatization in Africa

36005 THE WORLD BANK GROUP WASHINGTON, D.C. TP-8 TRANSPORT PAPERS SEPTEMBER 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Results of Railway Privatization in Africa Richard Bullock. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TRANSPORT SECTOR BOARD RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA Richard Bullock TRANSPORT THE WORLD BANK SECTOR Washington, D.C. BOARD © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www/worldbank.org Published September 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of a grant from TRISP, a partnership between the UK Department for International Development and the World Bank, for learning and sharing of knowledge in the fields of transport and rural infrastructure services. To order additional copies of this publication, please send an e-mail to the Transport Help Desk [email protected] Transport publications are available on-line at http://www.worldbank.org/transport/ RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................v Author’s Note ...................................................................................................................... -

Concept-Project-Information-Document-Integrated-Safeguards-Data-Sheet.Pdf

The World Bank Lake Tanganyika Transport Program - SOP1 Tanzania Phase (P165113) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Project Information Document/ Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet (PID/ISDS) Concept Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 07-Mar-2018 | Report No: PIDISDSC23776 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 8, 2018 Page 1 of 19 The World Bank Lake Tanganyika Transport Program - SOP1 Tanzania Phase (P165113) BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data OPS TABLE Country Project ID Parent Project ID (if any) Project Name Africa P165113 Lake Tanganyika Transport Program - SOP1 Tanzania Phase (P165113) Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA Apr 01, 2019 May 30, 2019 Transport & Digital Development Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing Ministry of Finance TANROADS, Tanzania Port Authority, Central Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency, East Africa Community Proposed Development Objective(s) The program development objective for the Lake Tanganyika Transport Program has been identified as the following: to facilitate the sustainable movement of goods and people to and across Lake Tanganyika, whilst strengthening the institutional framework for navigation and maritime safety. Financing (in USD Million) FIN_SUMM_PUB_TBL SUMMARY Total Project Cost 203.00 Total Financing 203.00 Financing Gap 0.00 DETAILS-NewFin3 Total World Bank Group Financing 203.00 World Bank Lending 203.00 January 8, 2018 Page 2 of 19 The World Bank Lake Tanganyika Transport Program - SOP1 Tanzania Phase (P165113) Environmental Assessment Category Concept Review Decision A-Full Assessment Track II-The review did authorize the preparation to continue Other Decision (as needed) B. Introduction and Context Regional Context 1. The economic performance of the East African Community (EAC) member countries—Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda—has been impressive over the last decade. -

Africa's Freedom Railway

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

Port of Maputo, Mozambique

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Transport Evolution presents 13 - 14 May 2019 | Port of Maputo, Mozambique 25+ expert speakers, including: Osório Lucas Chief Executive Officer, Maputo Port Development Company Col. Andre Ciseau Secretary General, Port Management Association of Eastern & Southern Africa (PMAESA) Clive Smith Chief Executive Officer, Walvis Bay Corridor Group, Namibia Johny Smith Chief Executive Officer, TransNamib Holdings Limited, Namibia Boineelo Shubane Director Operations, Botswana Railways, Botswana Building the next generation of ports and rail in Mozambique Host Port Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: Simultaneous conference translation in English and Portuguese will be provided Será disponibilizada tradução simultânea da conferência em Inglês e Português www.transportevolutionmz.com Welcome to the inaugural Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution Forum Ports and railways are leading economic engines for Mozambique, providing access to import and export markets, driving local job creation, and unlocking opportunities for the development of the local blue economy. Hosted by Maputo Port Development Company, Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution prepares the region’s ports and railways for the fourth industrial revolution. Day one of the extensive two-day conference will feature a high level keynote comprising of leading African ports and rail authorities and focus on advancing Intra-African trade. We then explore challenges, opportunities and solutions for improving regional integration and connectivity. Concluding the day, attendees will learn from local and international ports authorities and terminal operators about challenges and opportunities for ports development. Day two begins by looking at major commodities that are driving infrastructure development forward and what types of funding and investment opportunities are available. This is followed by a rail spotlight session where we will learn from local and international rail authorities and operators about maintenance and development projects. -

Familiarisation Tour of Mpulungu, Zambia

THE ENVIRONMENTAL COUNCIL OF ZAMBIA Pollution Control and Other Measures to protect Biodiversity in Lake Tanganyika (RAF/92/G32) FAMILIARISATION TOUR OF MPULUNGU A COMBINED SOCIO-ECONO0MICS AND ENVIRONMNETAL EDUCATION TOUR CONDUCTED FROM 2/2/99 TO 3/3/99 Munshimbwe Chitalu Assistant National Co-ordinator Socio-economics Co-ordinator National Coordination Office LUSAKA ZAMBIA July 2000 M p u l u n g u Vi s i t R e p o r t , So c i o - E c o n o m i c s / E n v i r o n m e n t a l Ed u c a t i o n Contents List of Acronyms ii Foreword iii Executive summary iv 1 HIGHLIGHTS 1 1 Environmental Education Activities 1 2 Conservation and Development Committees 1 3 Activities of CDCs 2 4 National Project coordination 3 5 The team 3 6 Approach and salutations 3 2 THE TOUR IN MORE DETAIL 4 1 The Aim 4 2 Specific Objectives 4 3 Findings 4 3.1 Community Development Officer (CDO) 4 3.2 Department of Fisheries (DoF) 5 3.3 Immigration Department 7 3.4 Mpulungu District Council 7 3.5 Mpulungu Harbor Corporation Limited 8 3.6 Mr. Mugala 8 3.7 The Provincial Agricultural Co-ordination Office (PACO) 9 3.8 Police Service 9 3.9 Senior Chief Tafuna 9 3.10 Stratum 2 CDC 9 3.11 Village CDCs 10 3 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 12 4 PROPOSED IMMEDIATE ACTIONS 14 Appendix I: Institutions and individuals visited 15 Appendix II: Itinerary 17 Appendix III: Resources 18 P A G E I M p u l u n g u Vi s i t R e p o r t , So c i o - E c o n o m i c s / E n v i r o n m e n t a l Ed u c a t i o n List of Acronyms AMIS Association of Micro-finance Institutions of Zambia ANSEC -

Towards a Regional Information Base for Lake Tanganyika Research

RESEARCH FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF THE FISHERIES ON LAKE GCP/RAF/271/FIN-TD/Ol(En) TANGANYIKA GCP/RAF/271/FIN-TD/01 (En) January 1992 TOWARDS A REGIONAL INFORMATION BASE FOR LAKE TANGANYIKA RESEARCH by J. Eric Reynolds FINNISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Bujumbura, January 1992 The conclusions and recommendations given in this and other reports in the Research for the Management of the Fisheries on Lake Tanganyika Project series are those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. They may be modified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequent stages of the Project. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or FINNIDA concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. PREFACE The Research for the Management of the Fisheries on Lake Tanganyika project (Tanganyika Research) became fully operational in January 1992. It is executed by the Food and Agriculture organization of the United Nations (FAO) and funded by the Finnish International Development Agency (FINNIDA). This project aims at the determination of the biological basis for fish production on Lake Tanganyika, in order to permit the formulation of a coherent lake-wide fisheries management policy for the four riparian States (Burundi, Tanzania, Zaïre and Zambia). Particular attention will be also given to the reinforcement of the skills and physical facilities of the fisheries research units in all four beneficiary countries as well as to the buildup of effective coordination mechanisms to ensure full collaboration between the Governments concerned. -

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment

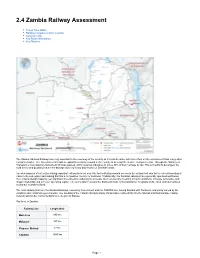

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment Travel Time Matrix Railway Companies and Consortia Capacity Table Key Route Information Key Stations The Zambia National Railways are very important to the economy of the country as it is a bulk carrier with less effect on the environment than many other transport modes. The Government intends to expand its railway network in the country to develop the surface transport sector. Through the Ministry of Transport, a new statutory instrument (SI) was passed, which requires industries to move 30% of their carriage by rail. This is in a bid to decongest the road sector and possibly reduce the damage done by heavy duty trucks on Zambian roads. The development of rail routes linking important exit points is not only vital for facilitating smooth access to the outside but also for the overall boosting of trade in the sub-region and making Zambia a competitive country for business. Traditionally, the Zambian railways have generally operated well below their original design capacity, yet significant investment is underway to increase their volumes by investing in track conditions, increase locomotive and wagon availability and increase operating capital. The rail network remains the dominant mode of transportation for goods on the local and international routes but is under-utilized. The main railway lines are the Zambia Railways, owned by Government and the TAZARA line, linking Zambia with Tanzania, and jointly owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments. The opening of the Chipata-Mchinji railway link provides connectivity into the Malawi and Mozambique railway network and further connects Zambia to the port of Nacala. -

Botswana Country Mining Guide

KPMG GLOBAL MINING INSTITUTE Botswana Country mining guide kpmg.com/mining KPMG INTERNATIONAL Strategy Series B | Botswana mining guide © 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. Contents Executive summary 2 New geographic expansion risk framework 3 Country snapshot 4 World Bank ranking: Ease of doing business 5 Type of government 6 Economy and fiscal policy 7 Heritage Foundation of Economic Freedom 8 Fraser Institute rankings 9 Sustainability and environment 12 Infrastructure development 17 Labor relations and employment situation 19 Inbound and outbound investment 19 Key commodities: Production and reserves 21 Major mining companies in Botswana 29 Foreign companies with operations in Botswana 29 © 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. 2 | Botswana mining guide Executive summary Since its independence in 1966, Botswana has witnessed good economic growth on the back of fiscal discipline and robust governance. The country has a strong legal framework, low prevalence of civil unrest or disorder and minimal government interference in the mining sector. Botswana also boasts infrastructure that is in better condition than several of its neighbors, which has assisted in boosting interest from international companies in the mining sector. Botswana is one of the world leaders in diamond production, with Russia competing closely. While Russia was the largest diamond producer in the world in terms of production volume in 2012, Botswana produced the most in terms of value, accounting for 23.6 percent of total global diamond production.