THE FAT of the LAND by Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crowne-Plaza-Moncton-6340074907

BANQUET & WEDDING MENU General Info Breakfasts Breaks Lunches Dinners Hors d’oeuvres Beverages Catering Info BANQUET GENERAL INFORMATION GUEST PACKAGES AUDIO VISUAL DECORATIONS Packages shipped to the hotel are requested to arrive The Crowne Plaza Moncton’s preferred supplier is The Crowne Plaza Moncton’s preferred supplier is no earlier than three days prior to the event or Freeman Audio Visual. The hotel will advise guidelines Unico Décor. The hotel will advise guidelines regarding guest arrival. Packages must include the following regarding equipment provided by other audio visual decorations provided by other decorating providers. information: guest’s name, meeting name and event providers. Charges will apply. Arrangements can be Charges will apply. Arrangements can be made with the date. Return shipping is the responsibility of the guest, made with the Crowne Meetings Director or with Crowne Meetings Director or with Unico Décor directly. or arrangements can be made through our Crowne Freeman Audio Visual directly. www.unicodecor.com • Direct: 506-382-0674 Meetings Director or Banquet Manager. A $25.00 per day www.freemanav-ca.com charge will be applied to any packages arriving more Direct: 506-854-6340 ext. 2222 OPTIONAL - TRADE SHOWS than three days prior to your event. Fax: 506-452-0805 The Crowne Meetings Director can recommend or [email protected] make arrangements with a show dresser for your trade show needs. CROWNE PLAZA MONCTON - DOWNTOWN / CENTREVILLE 1005 Main Street, Moncton, New Brunswick E1C 1G9 1 1.866.854.4656 | www.cpmoncton.com BANQUET & WEDDING MENU General Info Breakfasts Breaks Lunches Dinners Hors d’oeuvres Beverages Catering Info PLATED BREAKFASTS All plated breakfasts include chilled fruit juices, freshly brewed tea and coffee. -

12 Great Ofers

ISSUE 15 www.appetitemag.co.uk MAY/JUNE 2013 T ICKLE YOUR tasteBUDS... Bouillabaisse Lovely lobster Succulent squid Salmon salsa Monkfish ‘n’ mash All marine life is here... 1 ers seafood 2 great of and eat it Scan this code with your mobile H OOKED ON FISH? SO WHAT WILL YOUR ENVIRONMENTAL device to access the latest news CONSCIENCE ALLOW YOU TO LAND ON YOUR PLATE? on our website inside coastal capers // girl butcher // pan porn // garden greens // just desserts // join the Club PLACE YOUR Editor and committed ORDER 4 CLUB pescatarian struggles with Great places, great offers her environmental conscience. 7 FEED...BacK Tuna yes, basa no. Confused! Reader recipes and news 8 GIRL ABOUT TOON Our lady Laura’s adventures in food A veteran eco-campaigner (well, I went The upshot is that the whole thing is on a Save the Whale march when I was a minefield, but it’s a minefield I am 9 it’s A DATE a student) I like to consider myself fully determined to negotiate without losing any Fab places to tour and taste PEOPLE OF au fait with what one should and should limbs, so the Marine Conservation Society not buy and/or eat in order to keep one’s graphic is now safely tucked in my back 10 VEG WITH KEN social and environmental conscience intact. pocket, to be studied before purchasing Our new columnist Unfortunately, when it comes to fish, this anything which qualifies as a fish. I hope Ken Holland’s garden JESMOND causes extreme confusion, to the extent that this will widen my list of fish-it’s-okay- that I have frequently considered giving up to-eat; a list which has diminished alarmingly 19 GIRL BUTCHER my pescatarian ways altogether, basically in recent years for want of proper guidance. -

Montreal and New Orleans Cuisine

750ml House Specialties Red Wines 6oz 9oz bot Chaberton, Red - VQA, 12.7% - Langley, Fraser Valley (blend) 6¾ 9¾ 26 Brodeur’s Signature Caesar 9¾ Vodka (2 oz), Clamato juice, celery, olive, jumbo shrimp, bacon, dill pickle, cajun spiced rim Brodeur’s BISTRO McGuigan Black Label, Shiraz/Syrah - 12% - Australia 6¾ 9¾ 26 Sazerac (a New Orleans classic) 8¾ Montreal and New Orleans Cuisine Copper Moon - Cabernet Sauvignon - 13% - Okanagan Valley 7¾ 10¾ 30 Wisers Rye, absinthe, sugar, lemon, bitters (2 oz) Villa Teresa, Merlot (Organic) - 12% - Veneto, Italy 8¾ 11¾ 33 French 75 8¾ Ruffino, Chianti - 12.5% - Tuscany, Italy 8¾ 11¾ 33 Beefeater, sugar, fresh lemon, sparkling wine, served in a flute (2 oz) Single use MENU Tinto Negro, Malbec - 14% - Mendoza, Argentina 8¾ 11¾ 33 8¾ 16 oz 60 oz Huricane Pint Jug Black Cellar - Malbec Merlot - 13% - Ontario, Canada 26 White Rum, Dark Rum, orange, cranberry and lemon juice, passion fruit syrup and Sprite (2 oz) On Tap • Blanche de Chambly (craft).......................... 695 22 Jacob’s Creek, Cabernet Sauvignon - 14% - Barossa Valley, Australia 32 Sangria (white or red) 7¾ 95 White or red wine, fresh fruit, juice over ice - House made • Mennonite Farm Ale (craft).......................... 6 22 Beringer, Founders’ Estate, Merlot - 13.8% - Napa Valley, USA 32 Crisp straw coloured craft Kölsch, first brewed in Germany, then Lancaster County, now in BC Cono Sur, Cabernet Sauvignon/Syrah (Organic) - 14% - Chile 32 White Peach Bellini 7¾ Crushed ice, Rum, sparkling wine, Peach Schnappes, Sangria (2 oz) • Stella Artois.............................................................. 695 22 Mt. Boucherie, Merlot - VQA, 14.4% - Okanagan Valley 32 Moscow Mule 8¾ Vodka (2 oz), lime juice, ginger beer in a copper mug • Molson Canadian............................................... -

Ledistributeur 1Er Au 27 Octobre 2018 October 1St to 27Th, 2018

LEDISTRIBUTEUR 1ER AU 27 OCTOBRE 2018 OCTOBER 1ST TO 27TH, 2018 BRIDOR BONDUELLE 0,50 $ Baguette Tout simplement NOUVEAU 4 x 2 - 2,5 kg rabais/save surgelée NEW Frozen Simply baguette N Gratin dauphinois surgelé 16 x 350 g 0,50 $ Frozen gratin dauphinois 112854 115320 rabais/save Demi baguette surgelée N Chou-fleur en riz surgelé Frozen half french baguette Frozen riced cauliflowers 32 x 150 g S 116058 105957 5,00 $ rabais/save N Gratin de chou-fleur surgelé Pâte feuilletée en plaque Frozen cauliflower gratin surgelée S 116059 Frozen pastry puff slab Gratin de brocoli et pommes 15 x 10’’ - 20 x 350 g 1,00 $ N 129784 de terre surgelé rabais/save S Frozen broccoli and potato Croissant aux framboises MENU H-CUISINE gratin 116060 prêt-à-cuire N Café en grains mélange Ready-to-bake raspberry Signature croissant Signature blend coffee 44 x 90 g 1,00 $ beans 122923 rabais/save 5 x 908 g 55,40 $ 114020 N Café en grains espresso Espresso coffee beans 5 x 908 g 61,05 $ 115779 N Café filtre mélange MARTIN DESSERT Signature Tartelette pomme & sucre Signature coffe blend Frozen apple & sugar tartlet 50 x 57 g 35,65 $ 2 x 12 un 48,90 $ 113980 128866 Gâteau rond explosion de fromage surgelé Frozen round cheese cake TÉLÉPHONE SANS FRAIS / TOLL FREE : 1 888 832-6171 explosion 3 x 14 un 96,80 $ QUÉBEC TROIS-RIVIÈRES 114369 819 378-6155 418 831-8200 819 378-9333 418 831-8333 Petit lava au chocolat Small chocolate lava cake RIMOUSKI SAGUENAY 3 x 16 un 74,15 $ 28440 418 724-2400 418 549-4433 418 724-6470 418 696-5601 Gâteau Reine Elizabeth NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK -

Reconstituting Tbc Fur Trade Community of the Assiniboine Basin

Reconstituting tbc Fur Trade Community of the Assiniboine Basin, 1793 to 1812. by Margaret L. Clarke a thesis presented to The University of Winnipeg / The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Winnipeg, Manitoba MARCH 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 WdtïSûeet 395, nn, Wellingtwi WONK1AW WONK1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Ll'brary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disbi'bute or sefl reproduire, prêter, disbiiuer ou copies of this thesis iu microfo~a, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fomiats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format eectronicpe. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur consewe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A TksW/Pnicticw ribmitteà to the Faculty of Gruluate Studies of The University of Manitoba in parail fntfülment of the reqaifements of the degrce of brgarct 1. Clarke 1997 (a Permission hm been grantd to the Library of Tbe Univenity of Manitoba to lend or sen copies of this thcsis/practicam, to the National Librory of Canada to micronlm tbb thesis and to lend or seU copies of the mm, and to Dissertritions Abstmcts Intemationai to publish an abtract of this thcsidpracticam. -

The Ice Master: the Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ICE MASTER: THE DOOMED 1913 VOYAGE OF THE KARLUK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jennifer Niven | 402 pages | 10 Oct 2001 | THEIA | 9780786884469 | English | New York, NY, United States The Ice Master: The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk PDF Book Product Details About the Author. On August 11, the voluntary motion of the Karluk came to an end - the ice closed around the ship, the rain turned to snow, and the ultimate fate of the ship and crew became anyone's guess. I may re-read this one next winter. This story will haunt me for a while, though. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Other Editions Now they glowed like giant emeralds, diamonds, sapphires. The Karluk was not seaworthy. Indeed, McKinlay and the rest of the men felt themselves awaken to life when the moon and stars appeared. Open Preview See a Problem? The ice now began to crush the ship and supplies were moved on to the ice. This was much to the surprise of Bartlett because Stefansson himself had earlier told him that caribou were nearly extinct in the area of the Colville River. After almost twelve months battling the elements, twelve survivors were rescued, thanks to the heroic efforts of their captain, Bartlett, the Ice Master, who traveled by foot across the ice and through Siberia to find help. But a glory seeking explorer Named Vilhjalmur Stefansson found her to be cheap and available and thought she would do ju On Tuesday, June 17, a whaling boat named The Karluk set out on a scientific exploratory adventure that it was destined to never complete. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

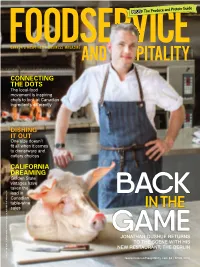

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook. -

Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird Mckinlay

Acc.12696 December 2006 Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird McKinlay National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Correspondence and papers of William Laird McKinlay, Glasgow. Background William McKinlay (1888-1983) was for most of his working life a teacher and headmaster in the west of Scotland; however the bulk of the papers in this collection relate to the Canadian National Arctic Expedition, 1913-18, and the part played in it by him and the expedition leader, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. McKinlay’s account of his experiences, especially those of being shipwrecked and marooned on Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia, were published by him in Karluk (London, 1976). For a rather more detailed list of nos.1-27, and nos.43-67 (listed as nos.28-52), see NRA(S) survey no.2546. Further items relating to McKinlay were presented in 2006: see Acc.12713. Other items, including a manuscript account of the expedition and the later activities of Stefansson – much broader in scope than Karluk – have been deposited in the National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa. A small quantity of additional documents relating to these matters can be found in NRA(S) survey no.2222, papers in the possession of Dr P D Anderson. Extent: 1.56 metres Deposited in 1983 by Mrs A.A. Baillie-Scott, the daughter of William McKinlay, and placed as Dep.357; presented by the executor of Mrs Baillie-Scott’s estate, November 2006. -

Medicine in Manitoba

Medicine in Manitoba THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS /u; ROSS MITCHELL, M.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY LIBRARY FR OM THE ESTATE OF VR. E.P. SCARLETT Medic1'ne in M"nito/J" • THE STORY OF ITS BEGINNINGS By ROSS MITCHELL, M. D. .· - ' TO MY WIFE Whose counsel, encouragement and patience have made this wor~ possible . .· A c.~nowledg ments THE LATE Dr. H. H. Chown, soon after coming to Winnipeg about 1880, began to collect material concerning the early doctors of Manitoba, and many years later read a communication on this subject before the Winnipeg Medical Society. This paper has never been published, but the typescript is preserved in the medical library of the University of Manitoba and this, together with his early notebook, were made avail able by him to the present writer, who gratefully acknowledges his indebtedness. The editors of "The Beaver": Mr. Robert Watson, Mr. Douglas Mackay and Mr. Clifford Wilson have procured informa tion from the archives of the Hudson's Bay Company in London. Dr. M. T. Macfarland, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, kindly permitted perusal of the first Register of the College. Dr. J. L. Johnston, Provincial Librarian, has never failed to be helpful, has read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions. Mr. William Douglas, an authority on the Selkirk Settlers and on Free' masonry has given precise information regarding Alexander Cuddie, John Schultz and on the numbers of Selkirk Settlers driven out from Red River. Sheriff Colin Inkster told of Dr. Turver. Personal communications have been received from many Red River pioneers such as Archbishop S. -

Food for Thought – Food “Aah! Think of Playing 7-Letter Bingos About FOOD, Yum!”– See Also Food for Thought – Drink Compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club

Food for Thought – Food “Aah! Think of playing 7-letter bingos about FOOD, Yum!”– See also Food for Thought – Drink compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club A 7s ABALONE AABELNO edible shellfish [n -S] ABROSIA AABIORS fasting from food [n -S] ACERBER ABCEERR ACERB, sour (sharp or biting to taste) [adj] ACERBIC ABCCEIR acerb (sour (sharp or biting to taste)) [adj] ACETIFY ACEFITY to convert into vinegar [v -FIED, -ING, -FIES] ACETOSE ACEEOST acetous (tasting like vinegar) [adj] ACETOUS ACEOSTU tasting like vinegar [adj] ACHENES ACEEHNS ACHENE, type of fruit [n] ACRIDER ACDEIRR ACRID, sharp and harsh to taste or smell [adj] ACRIDLY ACDILRY in acrid (sharp and harsh to taste or smell) manner [adv] ADSUKIS ADIKSSU ADSUKI, adzuki (edible seed of Asian plant) [n] ADZUKIS ADIKSUZ ADZUKI, edible seed of Asian plant [n] AGAPEIC AACEGIP AGAPE, communal meal of fellowship [adj] AGOROTH AGHOORT AGORA, marketplace in ancient Greece [n] AJOWANS AAJNOSW AJOWAN, fruit of Egyptian plant [n] ALBUMEN ABELMNU white of egg [n -S] ALFREDO ADEFLOR served with white cheese sauce [adj] ALIMENT AEILMNT to nourish (to sustain with food) [v -ED, -ING, -S] ALLIUMS AILLMSU ALLIUM, bulbous herb [n] ALMONDS ADLMNOS ALMOND, edible nut of small tree [n] ALMONDY ADLMNOY ALMOND, edible nut of small tree [adj] ANCHOVY ACHNOVY small food fish [n -VIES] ANISEED ADEEINS seed of anise used as flavoring [n -S] ANOREXY AENORXY anorexia (loss of appetite) [n -XIES] APRICOT ACIOPRT edible fruit [n -S] ARROCES ACEORRS ARROZ, rice [n] ARROZES AEORRSZ ARROZ, rice [n] ARUGOLA