Culinary Chronicles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

Crowne-Plaza-Moncton-6340074907

BANQUET & WEDDING MENU General Info Breakfasts Breaks Lunches Dinners Hors d’oeuvres Beverages Catering Info BANQUET GENERAL INFORMATION GUEST PACKAGES AUDIO VISUAL DECORATIONS Packages shipped to the hotel are requested to arrive The Crowne Plaza Moncton’s preferred supplier is The Crowne Plaza Moncton’s preferred supplier is no earlier than three days prior to the event or Freeman Audio Visual. The hotel will advise guidelines Unico Décor. The hotel will advise guidelines regarding guest arrival. Packages must include the following regarding equipment provided by other audio visual decorations provided by other decorating providers. information: guest’s name, meeting name and event providers. Charges will apply. Arrangements can be Charges will apply. Arrangements can be made with the date. Return shipping is the responsibility of the guest, made with the Crowne Meetings Director or with Crowne Meetings Director or with Unico Décor directly. or arrangements can be made through our Crowne Freeman Audio Visual directly. www.unicodecor.com • Direct: 506-382-0674 Meetings Director or Banquet Manager. A $25.00 per day www.freemanav-ca.com charge will be applied to any packages arriving more Direct: 506-854-6340 ext. 2222 OPTIONAL - TRADE SHOWS than three days prior to your event. Fax: 506-452-0805 The Crowne Meetings Director can recommend or [email protected] make arrangements with a show dresser for your trade show needs. CROWNE PLAZA MONCTON - DOWNTOWN / CENTREVILLE 1005 Main Street, Moncton, New Brunswick E1C 1G9 1 1.866.854.4656 | www.cpmoncton.com BANQUET & WEDDING MENU General Info Breakfasts Breaks Lunches Dinners Hors d’oeuvres Beverages Catering Info PLATED BREAKFASTS All plated breakfasts include chilled fruit juices, freshly brewed tea and coffee. -

12 Great Ofers

ISSUE 15 www.appetitemag.co.uk MAY/JUNE 2013 T ICKLE YOUR tasteBUDS... Bouillabaisse Lovely lobster Succulent squid Salmon salsa Monkfish ‘n’ mash All marine life is here... 1 ers seafood 2 great of and eat it Scan this code with your mobile H OOKED ON FISH? SO WHAT WILL YOUR ENVIRONMENTAL device to access the latest news CONSCIENCE ALLOW YOU TO LAND ON YOUR PLATE? on our website inside coastal capers // girl butcher // pan porn // garden greens // just desserts // join the Club PLACE YOUR Editor and committed ORDER 4 CLUB pescatarian struggles with Great places, great offers her environmental conscience. 7 FEED...BacK Tuna yes, basa no. Confused! Reader recipes and news 8 GIRL ABOUT TOON Our lady Laura’s adventures in food A veteran eco-campaigner (well, I went The upshot is that the whole thing is on a Save the Whale march when I was a minefield, but it’s a minefield I am 9 it’s A DATE a student) I like to consider myself fully determined to negotiate without losing any Fab places to tour and taste PEOPLE OF au fait with what one should and should limbs, so the Marine Conservation Society not buy and/or eat in order to keep one’s graphic is now safely tucked in my back 10 VEG WITH KEN social and environmental conscience intact. pocket, to be studied before purchasing Our new columnist Unfortunately, when it comes to fish, this anything which qualifies as a fish. I hope Ken Holland’s garden JESMOND causes extreme confusion, to the extent that this will widen my list of fish-it’s-okay- that I have frequently considered giving up to-eat; a list which has diminished alarmingly 19 GIRL BUTCHER my pescatarian ways altogether, basically in recent years for want of proper guidance. -

Montreal and New Orleans Cuisine

750ml House Specialties Red Wines 6oz 9oz bot Chaberton, Red - VQA, 12.7% - Langley, Fraser Valley (blend) 6¾ 9¾ 26 Brodeur’s Signature Caesar 9¾ Vodka (2 oz), Clamato juice, celery, olive, jumbo shrimp, bacon, dill pickle, cajun spiced rim Brodeur’s BISTRO McGuigan Black Label, Shiraz/Syrah - 12% - Australia 6¾ 9¾ 26 Sazerac (a New Orleans classic) 8¾ Montreal and New Orleans Cuisine Copper Moon - Cabernet Sauvignon - 13% - Okanagan Valley 7¾ 10¾ 30 Wisers Rye, absinthe, sugar, lemon, bitters (2 oz) Villa Teresa, Merlot (Organic) - 12% - Veneto, Italy 8¾ 11¾ 33 French 75 8¾ Ruffino, Chianti - 12.5% - Tuscany, Italy 8¾ 11¾ 33 Beefeater, sugar, fresh lemon, sparkling wine, served in a flute (2 oz) Single use MENU Tinto Negro, Malbec - 14% - Mendoza, Argentina 8¾ 11¾ 33 8¾ 16 oz 60 oz Huricane Pint Jug Black Cellar - Malbec Merlot - 13% - Ontario, Canada 26 White Rum, Dark Rum, orange, cranberry and lemon juice, passion fruit syrup and Sprite (2 oz) On Tap • Blanche de Chambly (craft).......................... 695 22 Jacob’s Creek, Cabernet Sauvignon - 14% - Barossa Valley, Australia 32 Sangria (white or red) 7¾ 95 White or red wine, fresh fruit, juice over ice - House made • Mennonite Farm Ale (craft).......................... 6 22 Beringer, Founders’ Estate, Merlot - 13.8% - Napa Valley, USA 32 Crisp straw coloured craft Kölsch, first brewed in Germany, then Lancaster County, now in BC Cono Sur, Cabernet Sauvignon/Syrah (Organic) - 14% - Chile 32 White Peach Bellini 7¾ Crushed ice, Rum, sparkling wine, Peach Schnappes, Sangria (2 oz) • Stella Artois.............................................................. 695 22 Mt. Boucherie, Merlot - VQA, 14.4% - Okanagan Valley 32 Moscow Mule 8¾ Vodka (2 oz), lime juice, ginger beer in a copper mug • Molson Canadian............................................... -

Ledistributeur 1Er Au 27 Octobre 2018 October 1St to 27Th, 2018

LEDISTRIBUTEUR 1ER AU 27 OCTOBRE 2018 OCTOBER 1ST TO 27TH, 2018 BRIDOR BONDUELLE 0,50 $ Baguette Tout simplement NOUVEAU 4 x 2 - 2,5 kg rabais/save surgelée NEW Frozen Simply baguette N Gratin dauphinois surgelé 16 x 350 g 0,50 $ Frozen gratin dauphinois 112854 115320 rabais/save Demi baguette surgelée N Chou-fleur en riz surgelé Frozen half french baguette Frozen riced cauliflowers 32 x 150 g S 116058 105957 5,00 $ rabais/save N Gratin de chou-fleur surgelé Pâte feuilletée en plaque Frozen cauliflower gratin surgelée S 116059 Frozen pastry puff slab Gratin de brocoli et pommes 15 x 10’’ - 20 x 350 g 1,00 $ N 129784 de terre surgelé rabais/save S Frozen broccoli and potato Croissant aux framboises MENU H-CUISINE gratin 116060 prêt-à-cuire N Café en grains mélange Ready-to-bake raspberry Signature croissant Signature blend coffee 44 x 90 g 1,00 $ beans 122923 rabais/save 5 x 908 g 55,40 $ 114020 N Café en grains espresso Espresso coffee beans 5 x 908 g 61,05 $ 115779 N Café filtre mélange MARTIN DESSERT Signature Tartelette pomme & sucre Signature coffe blend Frozen apple & sugar tartlet 50 x 57 g 35,65 $ 2 x 12 un 48,90 $ 113980 128866 Gâteau rond explosion de fromage surgelé Frozen round cheese cake TÉLÉPHONE SANS FRAIS / TOLL FREE : 1 888 832-6171 explosion 3 x 14 un 96,80 $ QUÉBEC TROIS-RIVIÈRES 114369 819 378-6155 418 831-8200 819 378-9333 418 831-8333 Petit lava au chocolat Small chocolate lava cake RIMOUSKI SAGUENAY 3 x 16 un 74,15 $ 28440 418 724-2400 418 549-4433 418 724-6470 418 696-5601 Gâteau Reine Elizabeth NOUVEAU-BRUNSWICK -

Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada

MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada Source: Planet Retail, 2012. Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Canada’s population, estimated at nearly 34.9 million in 2012, Executive Summary 2 has been gradually increasing and is expected to continue doing so in the near-term. Statistics Canada’s medium-growth estimate for Canada’s population in 2016 is nearly 36.5 million, Market Trends 3 with a medium-growth estimate for 2031 of almost 42.1 million. The number of households is also forecast to grow, while the Wine 4 unemployment rate will decrease. These factors are expected to boost the Canadian economy and benefit the C$36.8 billion alcoholic drink market. From 2011 to 2016, Canada’s economy Beer 8 is expected to continue growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2% and 3% (Euromonitor, 2012). Spirits 11 Canada’s provinces and territories vary significantly in geographic size and population, with Ontario being the largest 15 alcoholic beverages market in Canada. Provincial governments Distribution Channels determine the legal drinking age, which varies from 18 to 19 years of age, depending on the province or territory. Alcoholic New Product Launch 16 beverages must be distributed and sold through provincial liquor Analysis control boards, with some exceptions, such as in British Columbia (B.C.), Alberta and Quebec (AAFC, 2012). New Product Examples 17 Nationally, value sales of alcoholic drinks did well in 2011, with by Trend 4% growth, due to price increases and premium products such as wine, craft beer and certain types of spirits. -

Ontario's Local Food Report

Ontario’s Local Food Report 2015/16 Edition Table of Contents Message from the Minister 4 2015/16 in Review 5 Funding Summary 5 Achievements 5 Why Local Food Matters 6 What We Want to Achieve 7 Increasing Awareness 9 Initiatives & Achievements 9 The Results 11 Success Stories 13 Increasing Access 15 Initiatives & Achievements 15 The Results 17 Success Stories 19 Increasing Supply and Sales 21 Initiatives & Achievements 21 The Results 25 Success Stories 27 The Future of Local Food 30 Message from the Minister Ontario is an agri-food powerhouse. Our farmers harvest an impressive abundance from our fields and farms, our orchards and our vineyards. And our numerous processors — whether they be bakers, butchers, or brewers — transform that bounty across the value chain into the highest-quality products for consumers. Together, they generate more than $35 billion in GDP and provide more than 781,000 jobs. That is why supporting the agri-food industry is a crucial component of the Ontario government’s four-part plan for building our province up. Ontario’s agri-food industry is the cornerstone of our province’s success, and the government recognizes not only its tremendous contributions today, but its potential for growth and success in the future. The 2013 Local Food Act takes that support further, providing the foundation for our Local Food Strategy to help increase demand for Ontario food here at home, create new jobs and enhance the economic contributions of the agri-food industry. Ontario’s Local Food Strategy outlines three main objectives: to enhance awareness of local food, to increase access to local food and to boost the supply of food produced in Ontario. -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

2020 Canada Province-Level Wine Landscapes

WINE INTELLIGENCE CANADA PROVINCE-LEVEL WINE LANDSCAPES 2020 FEBRUARY 2020 1 Copyright © Wine Intelligence 2020 • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means) without the permission of the copyright owners. Application for permission should be addressed to Wine Intelligence. • The source of all information in this publication is Wine Intelligence unless otherwise stated. • Wine Intelligence shall not be liable for any damages (including without limitation, damages for loss of business or loss of profits) arising in contract, tort or otherwise from this publication or any information contained in it, or from any action or decision taken as a result of reading this publication. • Please refer to the Wine Intelligence Terms and Conditions for Syndicated Research Reports for details about the licensing of this report, and the use to which it can be put by licencees. • Wine Intelligence Ltd: 109 Maltings Place, 169 Tower Bridge Road, London SE1 3LJ Tel: 020 73781277. E-mail: [email protected]. Registered in England as a limited company number: 4375306 2 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. 62 ▪ Manitoba p. 72 ▪ Nova Scotia p. 82 ▪ Appendix p. 92 ▪ Methodology p. 100 3 CONTENTS ▪ How to read this report p. 5 ▪ Management summary p. 7 ▪ Wine market provinces: key differences p. 21 ▪ Ontario p. 32 ▪ Alberta p. 42 ▪ British Colombia p. 52 ▪ Québec p. -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

Connecting the Dots

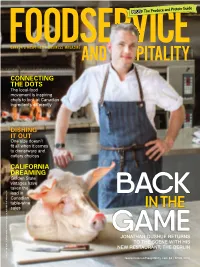

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook. -

Wine Tourism Insight

Wine Tourism Product BUILDING TOURISM WITH INSIGHT WINE October 2009 This profile summarizes information on the British Columbia wine tourism sector. Wine tourism, for the purpose of this profile, includes the tasting, consumption or purchase of wine, often at or near the source, such as wineries. Wine tourism also includes organized education, travel and celebration (i.e. festivals) around the appreciation of, tasting of, and purchase of wine. Information provided here includes an overview of BC’s wine tourism sector, a demographic and travel profile of Canadian and American travellers who participated in wine tourism activities while on pleasure trips, detailed information on motivated wine travellers to BC, and other outdoor and cultural activities participated in by wine travellers. Also included are overall wine tourism trends as well as a review of Canadian and US wine consumption trends, motivation factors of wine tourists, and an overview of the BC wine industry from the supply side. Research in this report has been compiled from several sources, including the 2006 Travel Activities and Motivations Study (TAMS), online reports (i.e. www.winebusiness.com), Statistics Canada, Wine Australia, (US) Wine Market Council, Winemakers Federation of Australia, Tourism New South Wales (Australia) and the BC Wine Institute. For the purpose of this tourism product profile, when describing results from TAMS data, participating wine tourism travellers are defined as those who have taken at least one overnight trip in 2004/05 where they participated in at least one of three wine tourism activities (1) Cooking/Wine tasting course; (2) Winery day visits; or (3) Wine tasting school.