Eurasian Journal of Business and Management, 9(2), 2021, 164-183 DOI: 10.15604/Ejbm.2021.09.02.005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Bursa 2019

List of participants - 29/07/2021 COMAG ENGINEERING GMBH GANJA AUTOMOTIVE PLANT COMAG Engineering is the specialist for solutions in the Car and Bus producers production of surface-clad automotive interior components as Azerbaijan well as innovative system solutions for other industries Austria BELCOMMUNNASH MAZ Public Transport manufacturer Minsk automobile plant- trucks Belarus Belarus MAZ-MAN OJSC BELAZ Heavy vehicles producer Major world manufacturer of mining dump trucks of heavy-duty Belarus and super-size load capacity, as well as the other heavy vehicles, being used in mining and construction branches of industry. Belarus VOLAT AUTOMOTIVE PARTS MANUFACTURERS' ASSOCIATION (APMA) Trucks and heavy vehicles Automotive parts manufacturers association Canada Belarus Canada BMW CHINA SERVICES LTD IMPRO INTERNATIONAL LIMITED Automotive manufacturer manufacturing engineered castings and precision machined China products China ZETOR TRACTOR AS 3P PRODUITS PLASTIQUES PERFORMANTS +420 533 430 111 Products designs, develops and manufactures solutions in high Czech Republic performance plastics and composites (PTFE, PFA, PEEK, etc, virgin or filled) to answer your challenges. France A2MAC1 - AUTOMOTIVE BENCHMARKING EIFFAGE ENERGIE SYSTÈMES - CLEMESSY World leader in automotive benchmarking From audit to design, integration to completion, commissioning France to maintenance, our specialists support all sectors of industry, in terms of infrastructure and utilities as well as processes. France PROTECHNIC SA ROCTOOL SA Production of thermoadhesive nets, webs and films in roll form From interior cosmetic parts to lightweighting of structural for dry lamination components, Roctool is the key to add value, fonctionality and France decoration to the product range. France SPAREX VALEO Spare parts for agriculture vehicules Valeo is an independent group, fully focused on the design, France manufacturing and sale of automotive spare parts France advanced business events - 35/37 rue des abondances - 92513 Boulogne-Billancourt Cedex - France www.advbe.com - [email protected] - Tel. -

171101 Final PRODOC Autom

UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION Project of the Republic of Belarus Project number: ID 170165 Project title: Institutional strengthening and policy support to upgrade the component manufacturers in the automotive sector in the Republic of Belarus Project phase Phase II Thematic area code GC2 Advancing Economic Competitiveness Starting date: Phase I: 2014–2017 Phase II: 2017–2019 Duration: Phase I: 30 months Phase II: 15 months Project site: Republic of Belarus Government Coordinating agency: National Academy of Sciences of Belarus Main counterpart: Ministry of Economy and Ministry of Industry of the Republic of Belarus Executing agency: UNIDO Donor: Russian Federation Project Inputs Phase I: - Project costs: USD 880,530 - Support costs 13%: USD 114,470 - Total project costs: USD 995,000 Project Inputs Phase II: - Project costs: USD 398,230 - Support costs 13%: USD 51,770 - Total project costs: USD 450,000 (the Russian voluntary contribution to UNIDO IDF) Brief description: The overall objective of the project is to assist the automotive component suppliers in the Republic of Belarus to meet the requirements of Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and the first-tier automotive component manufacturers. More specifically, the project foresees: Enhancing the performance of participating suppliers in the automotive component industry in the Republic of Belarus to ensure their international competitiveness through enterprises oriented direct shop floor interventions, at a first step on a pilot-bases, and finally through selected business support and advisory institutions. Upgrading the relevant support institutions through strengthening institutional set-up, optimization of the service portfolio and development of a base of well-trained national engineers. -

![Pdf [2019-05-25] 21](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2261/pdf-2019-05-25-21-742261.webp)

Pdf [2019-05-25] 21

ISSN 1648-2603 (print) VIEŠOJI POLITIKA IR ADMINISTRAVIMAS ISSN 2029-2872 (online) PUBLIC POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION 2019, T 18, Nr. 3/2019, Vol. 18, Nr. 3, p. 46-58 The World Experience and a Unified Model for Government Regulation of Development of the Automotive Industry Illia A. Dmytriiev, Inna Yu. Shevchenko, Vyacheslav M. Kudryavtsev, Olena M. Lushnikova Department of Economics and Entrepreneurship Kharkiv National Automobile and Highway University 61002, 25 Yaroslav Mudriy Str., Kharkiv, Ukraine Tetiana S. Zhytnik Department of Social Work, Social Pedagogy and Preschool Education Bogdan Khmelnitsky Melitopol State Pedagogical University 72300, 20 Hetmanska Str., Melitopol, Ukraine http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.ppaa.18.3.24720 Abstract. The article summarises the advanced world experience in government regulation of the automotive industry using the example of the leading automotive manufacturing countries – China, Japan, India, South Korea, the USA, and the European Union. Leading approach to the study of this problem is the comparative method that has afforded revealing peculiarities of the primary measures applied by governments of the world to regulate the automotive industry have been identified. A unified model for government regulation of the automotive industry has been elaborated. The presented model contains a set of measures for government support for the automotive industry depending on the life cycle stage (inception, growth, stabilisation, top position, stagnation, decline, crisis) of the automotive industry and the -

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study Dear Reader, Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study. 1 Growth is back on the agenda. While the industry environment remains challenging, the key question is how premium commercial vehicle OEMs can grow profitably and sustainably in a 2 global setting. 3 This year we present a truly international outlook, prepared by the Deloitte Global Commercial 4 Vehicle Team. After speaking with a selection of European OEM senior executives from around the world, we prepared this innovative study. It combines industry and Deloitte expert 5 insight with a wide array of data. Our experts draw on first-hand knowledge of both country 6 Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier and industry-specific challenges. We hope you will find this report useful in developing your future business strategy. To the 7 many executives who took the time to respond to our survey, thank you for your time and valuable input. We look forward to continuing this important strategic conversation with you. Using this report In each chapter you will find: • A summary of the key messages and insights of the chapter and an overview of the survey responses regarding each topic Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier • Detailed materials supporting our findings Partner Automotive Director Strategy & Operations and explaining the impacts for the OEMs © 2014 Deloitte Consulting GmbH Table of Contents The global truck market outlook is optimistic Yet, slow growth in key markets will increase competition while growth is shifting 1. Executive Summary to new geographies 2. -

Adressverzeichnis

ADRESSVERZEICHNIS ANHÄNGER & AUFBAUTEN . .Seite 11–13 BUSSE. .Seite 13–16 LKW und TRANSPORTER . .Seite 16–19 SPEZIALFAHRZEUGE . .Seite 19–22 ANHÄNGER & Aebi Schmidt ALF Fahrzeugbau Andreoli Rimorchi S.r.l. Deutschland GmbH GmbH & Co.KG Via dell‘industria 17 AUFBAUTEN Albtalstraße 36 Gewerbehof 12 37060, Buttapietra (Verona) 79837 St. Blasien 59368 Werne ITALIEN Acerbi Veicoli Industriali S.p.A. Tel. +49.7672-412-0 Tel. +49.2389 98 48-0 Tel. +39 045 666 02 44 Strada per Pontecurone, 7 www.aebi-schmidt.com www.alf-fahrzeugbau.de www.andreoli-ribaltabili.it 15053 Castelnuovo Scrivia (AL) ITALIEN Agados spol. s.r.o. ALHU Fahrzeugtechnik GmbH Andres www.acerbi.it Rumyslová 2081 Borstelweg 22 Hermann Andres AG 59401 Velké Mezirici 25436 Tornesch Industriering 42 Achleitner Fahrzeugbau TSCHECHIEN Tel. +49.4122 - 90 67 00 3250 Lyss Innsbrucker Straße 94 Tel. +420 566 653 311 www.alhu.de SCHWEIZ 6300 Wörgl www.agados.cz Tel. +41 32 387 31 61 Asch- ÖSTERREICH AL-KO www.andres-lyss.ch wege & Tönjes Aucar- Tel. +43 5332-7811-0 Agados Anhänger Handels Alois Kober GmbH Zur Schlagge 17 Trailer SL www.achleitner.com GmbH Ichenhauser Str. 14 Annaburger Nutzfahrzeuge 49681 Garrel Pintor Pau Roig 41 2-3 Schwedter Str. 20a 89359 Kötz GmbH Tel. +49.4474-8900-0 08330 Premià de mar, Barcelona Ackermann Aufbauten & 16287 Schöneberg Tel. +49.8221-97-449 Torgauer Straße 2 www.aschwege-toenjes.de SPANIEN Fahrzeugvertrieb GmbH Tel. +49.33335 42811 www.al-ko.de 06925 Annaburg Tel. +34 93 752 42 82 Am Wallersteig 4 www.agados.de Tel. +49.35385-709-0 ASM – Equipamentos www.aucartrailer.com 87700 Memmingen-Steinheim Altinordu Trailer www.annaburger.de de Transporte, S Tel. -

TIBO-2019 Cover ENGL.Indd

• LARGEST ICT FORUM IN BELARUS • NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR COMMUNICATIONS XXVI INTERNATIONAL FORUM ON INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES APRIL 8-12,2019 MINSK, BELARUS REPORT ON XXVI ICT FORUM TIBO-2019 APRIL 8-12, 2019 MINSK, BELARUS CONTENTS CONTENTS Members of the Organizing Committee of Tibo-2019 Forum 4 Welcome speeches to the participants of TIBO-2019 Forum 6 About TIBO-2019 Forum 16 Official opening of the forum and the Plenary Session “Strategy of Digital Transformation” 22 Official opening ceremony of the XXVI International Exhibition on Information and Communication Technologies TIBO-2019 29 Official guests of TIBO-2019 33 Interviews with participants and guests of TIBO-2019 34 Signing the agreements, bilateral meetings 39 II Eurasian Digital Forum 41 Session of the Eurasian Economic Commission “Projects of Digital Agenda for the Eurasian Economic Union” 44 III BELARUSIAN ICT SUMMIT 49 Plenary session “Modern Technological Trends” 51 SECTION A: Broadband access technologies. Cloud technologies 54 SECTION B: Internet of Things technologies. Artificial intelligence 57 SECTION C: Security and protection of information 58 SECTION D: Ways of digital transformation in industry 59 SECTION E: Forum on Internet-security for children 61 SECTION F: Unmanned aerial vehicles 63 SECTION G: Innovative financial technologies 65 IV International Conference “Industry 4.0 – Innovation in the Manufacturing Sector. Industry solutions” 67 IV International Scientific and Practical Conference “SMART LEARNING 2019 – Innovative Technologies in Education” -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/334 15 March 2016

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/S/334 15 March 2016 (16-1479) Page: 1/163 Trade Policy Review Body TRADE POLICY REVIEW REPORT BY THE SECRETARIAT UKRAINE This report, prepared for the first Trade Policy Review of Ukraine, has been drawn up by the WTO Secretariat on its own responsibility. The Secretariat has, as required by the Agreement establishing the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (Annex 3 of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization), sought clarification from Ukraine on its trade policies and practices. Any technical questions arising from this report may be addressed to Cato Adrian (tel: 022/739 5469); and Thomas Friedheim (tel: 022/739 5083). Document WT/TPR/G/334 contains the policy statement submitted by Ukraine. Note: This report is subject to restricted circulation and press embargo until the end of the first session of the meeting of the Trade Policy Review Body on Ukraine. This report was drafted in English. WT/TPR/S/334 • Ukraine - 2 - CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 7 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Main Features .......................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Economic Developments ............................................................................................ 11 1.3 Developments in Trade ............................................................................................. -

CATALOGUE Tribo Is a Steadily Growing Group of Companies, Founded in 1979

friction products manufacturer CATALOGUE Tribo is a steadily growing group of companies, founded in 1979. There is a modern testing laboratory Tribo is the largest manufacturer of friction products in the East European region. located at Tribo, which makes it possible to perform quality control and develop the new products. Tribo produces more than 800 different products for such industrial groups as railway transport, commercial vehicles, agricultural, industrial and special equipment. Tribo production meets the following CIS and European The coordinated work and development of the company are provided by subsidiaries: quality standards: Tribo Tools (metal working and mold production) (friction products development and testing) Tribo R&D ISO 9001:2015 Tribo Rail UK (friction products for the European market) ISO 14001:2015 Tribo Trade (raw materials wholesale trade for the chemical industry) IATF 16949:2016 ECE R90 OUR CLIENTS: CONTENTS Railway products ....................................................................................... 8 Brake pads ................................................................................................... 14 Special vehicles products ........................................................................ 20 Brake linings ............................................................................................... 26 Brake discs and clutch facings ............................................................. 34 Ж/Д ПРОДУКЦИЯ Geosynthetics ........................................................................................... -

Catalogue of Products YMZ 2015 V 1 0

DIESEL ENGINES CATALOGUE OF PRODUCTS DIESEL ENGINES AND POWER UNITS Euro-4 Regulation 96-02 Euro-3 Regulation 96-01 Euro-2 Euro-1 Regulation 96 Euro-0 turbo Euro-0 4,43 liters 120-190 h.p. 105 x128 105 6,65 liters 240-320 h.p. 11,12 liters 285-420 h.p. 123x156 11,15 liters 150-300 h.p. 14,86 liters 180-420 h.p. 130x140 22,3 liters 300-500 h.p. 25,86 liters 500-800 h.p. 140x140 2 3 Contents Introduction Classification of diesel engines YMZ. 4 GAZ Group is the largest manufacturer Introduction. 5 of commercial vehicles in Russia. IN-LINE DIESEL ENGINES GAZ Group produces light and medium-duty commercial vehicles, YMZ-530 family buses, heavy-duty trucks, passenger cars, power trains and L-4 . 8 automotive components at its 13 plants located in 8 regions of L-6 . 10 Russia. YMZ-650 family L-6 . 14 GAZ Group leads the Russian commercial vehicles market, with JSC"" Avtodizel (YaMZ), a part of GAZ Group, 50% of the LCV segment and 65% of the bus segment. GAZelle V- TYPE DIESEL ENGINES is the leading Russian manufacturer of diesel engines. Next, a new generation LCV, is the Company’s flagship. It was founded in1916. It specializes in development Family 130х140 and manufacture of diesel engines for different V-6 . 22 GAZ Group is the leader among Russian automakers building applications with a displacement of 4-26 liters V-8 . 36 environmentally friendly modes of transport, including vehicles and power of 12 0-800 h.p., gearboxes, clutches, V-12 . -

Zil-En-En Catalog

KAUCHUK Page: 2 Резинотехнические изделия и резиновые смеси от производителя ZIL RING 38Х1,9 (039-042-19-2-2) Application: ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZ valve control brakes of the semi-trailer, Steering (metering pump) T-30A-80, ND-80K MTZ-100, Crane KS-4372VVehicle: ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZ, T-30A-80, MTZ-100, KS-4372VNormative documentation: ГОСТ 18829-73Catalog number: 039-042-19-2-2 Read More SKU: 33022 Price: 2,66 UAH Категории: KAMAZ, MAZ, O-rings, Rubber Parts for Agricultural Machinery, Rubber Parts for Special Machinery, Rubber Parts for Trucks, Tractors, Truck Cranes, ZIL RING 24,5Х1,9 (025-028-19-2-3) Application: air dispenserVehicle: ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZNormative documentation: ГОСТ 18829-73Catalog number: 025-028-19-2-3 Read More SKU: 32852 Price: 2,28 UAH Категории: KAMAZ, MAZ, O-rings, Rubber Parts for Trucks, ZIL Телефоны для заказа: +380 67 000 1997 +380 95 048 1000 +380 93 621 1120 KAUCHUK Page: 3 Резинотехнические изделия и резиновые смеси от производителя O-RING 56,75Х3,53 (100-3522029) Application: Trailer brake control valve with two-wire drive ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZ, URAL, K-744P1, KrAZ-260Vehicle: ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZ, Ural, tracktor Kirovetz K-744P1, КRАZ-260Normative documentation: ТУ У 6 00152135.028-96Catalog number: 56,75х3,53 Read More SKU: 32870 Price: 5,66 UAH Категории: KAMAZ, KRAZ, MAZ, Rubber Parts for Agricultural Machinery, Rubber Parts for Trucks, Tractors, Ural, ZIL TWO-LINE VALVE SEALING FOR ZIL (100-3562024) Application: brakes, two-line valve in the assemblyVehicle: ZIL, KAMAZ, MAZ, КRАZNormative documentation: ТУ 38 1051254-82Catalog -

Autobusiness N 138 Eng.Pdf

content Content Car Marke……………………………………………………………..……………………………………...………….. 3 Commercial Vehicles………………………………………...….……………………………………………………. 21 Foreign Investors: Business Organization in Russia ……………………………………………..…….……… 27 Auto component sector – no way out?………………………….……….………………………………………… 31 DMS: Auto Dealers’ Experience …………………………………………………………………………………….. 34 A Car on Demand …………………………………………………………………………………………………..…. 38 Power Plant ……………………………………………………………………....………………………...………….. 43 Model Highway Initiative ……………..…………………………………………………………………...………….. 43 Autobusiness [138] June 2013 | 2 first quarter results Car Market The car segment of the first quarter of 2013 is characterized by a pronounced stability of its indices. The production and sales growth was insignificant, in comparison with the first quarter of 2012. The increase in the share of foreign cars in the car production and sales structure also slowed down. Car Production Over the first three months of 2013, in Russia, 452.5 thousand cars were manufactured, which is only a 0.62% increase on the production result for the same period of 2012. Shares of Russian and foreign cars in the production structure also remained almost unchanged. In January-March 2013, 140.6 thousand cars of Russian brands were produced, which amounted to 31.07% of the total production volume. For comparison, In January-March 2012, their share was equal to 31.11%. Despite the total production volume stability, in the first quarter of 2013, the dynamics of cars, produced by various manufacturers, differed significantly. So, most enterprises, producing cars of Russian brands, showed the negative production dynamics. AVTOVAZ’s car production decreased by 4.63%, in particular, due to the assembly termination of Lada Kalina cars of the previous generation and preparation for the production of a new model of Kalina cars. The car production of Ulyanovsk Automobile Plant also decreased, by 14.1%. -

Project Document

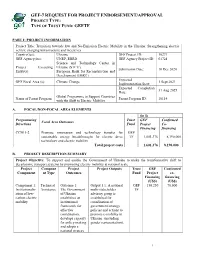

GEF-7 REQUEST FOR PROJECT ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEFTF PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Transition towards low and No-Emission Electric Mobility in the Ukraine: Strengthening electric vehicle charging infrastructure and incentives Country(ies): Ukraine GEF Project ID: 10271 GEF Agency(ies): UNEP, EBRD GEF Agency Project ID: 01724 Science and Technology Center in Project Executing Ukraine (STCU), Submission Date: 10 Dec 2020 Entity(s): European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) Expected GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change 1 Sept 2021 Implementation Start: Expected Completion 31 Aug 2025 Date: Global Programme to Support Countries Name of Parent Program Parent Program ID: 10114 with the Shift to Electric Mobility A. FOCAL/NON-FOCAL AREA ELEMENTS (in $) Programming Trust GEF Confirmed Focal Area Outcomes Directions Fund Project Co- Financing financing CCM 1-2 Promote innovation and technology transfer for GEF sustainable energy breakthroughs for electric drive TF 1,601,376 8,190,000 technology and electric mobility Total project costs 1,601,376 8,190,000 B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION SUMMARY Project Objective: To support and enable the Government of Ukraine to make the transformative shift to decarbonize transport systems by promoting electric mobility at national scale Project Compone Project Project Outputs Trust GEF Confirmed Component nt Type Outcomes Fund Project co- Financing financing (US$) (US$) Component 1: Technical Outcome 1: Output 1.1: A national GEF 150,250 70,000 Institutionaliz Assistance The Government multi-stakeholder TF ation of low- of Ukraine advisory group is carbon electric establishes an established for mobility institutional coordination of framework for government strategy, effective policies and actions to coordination, promote e-mobility in develops capacity Ukraine.