Passenger Vehicles Industry and Trade Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Dr. Eyal Nir May, 2015 CURRICULUM VITAE • Personal Details Name: Eyal Nir Date and place of birth: 06-08-1971 Address and telephone number at work: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel; Office: 972(0)8-6428474, Lab: 972(0)8-6428472 Home Address: HaAtad Street, #11, Apartment #14, Tel-Aviv, 66843, Israel, Phone: 972(0)50-6994468 • Education B.Sc. (1994-1997) Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, Chemistry M.Sc. (1998-1999) Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, Physical-Chemistry Name of advisor: Prof. Mattanjah de Vries Title of the Thesis: Building Blocks of DNA, Gas-Phase Research Ph.D. (1999-2003) Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, Physical-Chemistry Name of advisor: Prof. Mattanjah de Vries Title of the Thesis: Building Blocks of DNA, Gas-Phase Research • Employment History 10/2008 – Current: Senior Lecturer, Department of Chemistry, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev 2003 – 2008: Research Associate (Post-doctorate), Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University California Los-Angeles (UCLA), USA 2001 – 2002: Researcher, Department of Physical-Chemistry, University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), USA 1997 – 2001: Teaching Assistant, Chemistry Department, Hebrew University, Israel Dr. Eyal Nir page 2 • Professional Activities Ad-hoc reviewer for peer-reviewed journals Science, Journal of the American Chemical Society, Nano Letters, Angewandte Chemie, ACS-Nano, The Journal of Physical Chemistry (Letters), Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, Molecules, Nanoscale, PLOS ONE, Methods, Scientific Reports, A • Educational Activities (a) Courses Taught 1. Physical-Chemistry-I course for 2nd year undergraduate pharmacist (2009, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015), biologist, geologists, computer science and health science students (2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015) 2. -

Michigan Auto Project Progress Report - December 2000 I Inaugural Progress Report Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project

A VOLUNTARY POLLUTION PREVENTION AND RESOURCE CONSERVATION PARTNERSHIP ADMINISTERED BY: Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Environmental Assistance Division DECEMBER, 2000: 1st ISSUE John Engler, Governor • Russell J. Harding, Director www.deq.state.mi.us ACKNOWLEDGMENTS DaimlerChrysler Corporation, Ford Motor Company, General Motors Corporation and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) thank the Auto Project Stakeholder Group members for providing advice to the Auto Project partners and facilitating public information exchange. The Auto Companies and MDEQ also acknowledge the guidance and counsel provided by the US EPA Region V. CONTACTS FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For information regarding the Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project Progress Report, contact DaimlerChrysler, Ford, or General Motors at the addresses listed below or the Environmental Assistance Division of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality at 1-800-662-9278. DaimlerChrysler Ford Doug Orf, CIMS 482-00-51 Sue Rokosz DaimlerChrysler Corporation Ford Motor Company 800 Chrysler Drive One Parklane Blvd., Suite 1400 Auburn Hills, MI 48326-2757 Dearborn, MI 48126 [email protected] [email protected] General Motors MDEQ Sandra Brewer, 482-303-300 Anita Singh Welch General Motors Corporation Environmental Assistance Division 465 W. Milwaukee Ave. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Detroit, MI 48202 P.O. Box 30457 [email protected] Lansing, MI 48909 [email protected] Michigan Auto Project Progress Report - December 2000 i Inaugural Progress Report Michigan Automotive Pollution Prevention Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Foreward iv I. Executive Summary Project Overview 1 Activities and Accomplishments 4 Focus on Michigan 11 Auto Company Profiles II. DaimlerChrysler Corporation Project Status 12 Activities and Accomplishments 14 Focus on Michigan 16 III. -

Nanotechnology Publications: Leading Countries and Blocs

Date: January 29, 2010 Author Note: I provide links and a copy of my working paper (that you may make freely available on your website) and a link to the published paper. Link to working paper: http://www.cherry.gatech.edu/PUBS/09/STIP_AN.pdf Link to published paper: http://www.springerlink.com/content/ag2m127l6615w023/ Page 1 of 1 Program on Nanotechnology Research and Innovation System Assessment Georgia Institute of Technology Active Nanotechnology: What Can We Expect? A Perspective for Policy from Bibliographical and Bibliometric Analysis Vrishali Subramanian Program in Science, Technology and Innovation Policy School of Public Policy and Enterprise Innovation Institute Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332‐0345, USA March 2009 Acknowledgements: This research was undertaken at the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) and at Georgia Tech with support by the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) and Center for Nanotechnology in Society at Arizona State University ( sponsored by the National Science Foundation Award No. 0531194). The findings contained in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) or the National Science Foundation. For additional details, see http://cns.asu.edu (CNS‐ASU) and http://www.nanopolicy.gatech.edu (Georgia Tech Program on Nanotechnology Research and Innovation Systems Assessment).The author wishes to thank Dave Rejeski, Andrew Maynard, Mihail Roco, Philip Shapira, Jan Youtie and Alan Porter. Executive Summary Over the past few years, policymakers have grappled with the challenge of regulating nanotechnology, whose novelty, complexity and rapid commercialization has highlighted the discrepancies of science and technology oversight. -

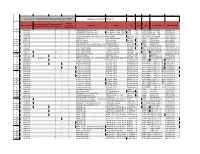

EPA Regulated PCB Transformer Data

A B C D E F G H I J K Transformers Containing Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) Database Last Modified: 13-Sep-19 1 Number Date De-Registered/ Number Original Date Registered Remaining Company Street City State Zip Contact Name Contact Phone Latest Removal Date Transformers 2 Transformers 3 12-Jan-06 15 15 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 4 12-Jan-06 31 31 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 5 10-Apr-06 32 32 30 RMS/RMR (Tetra Tech, Inc) 816 13th Street, Suite 207, BuiVAFB CA 93437-5212Steven L. Daly 805-605-7336 6 16-Dec-98 35 35 3448US Army Armor Center and Fort Knox Not Provided Fort Knox KY 40121-5000Louis Barnhart 502-624-3629 7 9-Mar-18 2 2 83 Griffith St, LLC 3333 Allen Parkway Salem NJ 08079 Harold Polk (346) 970-8909 8 21-Dec-98 1 1 AAF International 215 Central Ave. Louisville KY 40208 Ron Unthank 502-637-0221 9 21-Dec-98 1 1 AAF International 215 Central Ave. Louisville KY 40208 Ron Unthank 502-637-0221 10 26-Jan-10 12 12 Abitibi Bowater (Formerly US Alliance Coos17589 Plant Road Coosa PinesAL 35044 Brian Smith 256-378-2126 11 20-Oct-08 13 13 Acero Junction Inc. (FKA Severstal Wheelin1134 Market Street Wheeling WV 26003 Patrick J. Smith 740-283-5542 12 3-Dec-98 2 2 Acme Steel Company 13500 S. -

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study

Truck Market 2024 Sustainable Growth in Global Markets Editorial Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study Dear Reader, Welcome to the Deloitte 2014 Truck Study. 1 Growth is back on the agenda. While the industry environment remains challenging, the key question is how premium commercial vehicle OEMs can grow profitably and sustainably in a 2 global setting. 3 This year we present a truly international outlook, prepared by the Deloitte Global Commercial 4 Vehicle Team. After speaking with a selection of European OEM senior executives from around the world, we prepared this innovative study. It combines industry and Deloitte expert 5 insight with a wide array of data. Our experts draw on first-hand knowledge of both country 6 Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier and industry-specific challenges. We hope you will find this report useful in developing your future business strategy. To the 7 many executives who took the time to respond to our survey, thank you for your time and valuable input. We look forward to continuing this important strategic conversation with you. Using this report In each chapter you will find: • A summary of the key messages and insights of the chapter and an overview of the survey responses regarding each topic Christopher Nürk Michael A. Maier • Detailed materials supporting our findings Partner Automotive Director Strategy & Operations and explaining the impacts for the OEMs © 2014 Deloitte Consulting GmbH Table of Contents The global truck market outlook is optimistic Yet, slow growth in key markets will increase competition while growth is shifting 1. Executive Summary to new geographies 2. -

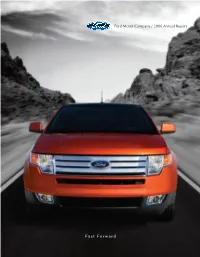

Fast Forward 2006 Annual Report

Ford Motor Company Ford Motor Company / 2006 Annual Report Fast Forward 2006 www.ford.com Annual Fast Forward Ford Motor Company • One American Road • Dearborn, Michigan 48126 Report cover printer spreads_V2.indd 1 3/14/07 7:41:56 PM About the Company Global Overview* Ford Motor Company is transforming itself to be more globally integrated and customer-driven in the fiercely competitive world market of the 21st century. Our goal is to build more of the products that satisfy the wants and needs of our customers. We are working as a single worldwide team to improve our cost structure, raise our Automotive Core and Affi liate Brands quality and accelerate our product development process to deliver more exciting new vehicles faster. Featured on the front and back cover of this report is one of those vehicles, the 2007 Ford Edge. Ford Motor Company, a global industry leader based in Dearborn, Michigan, manufactures or distributes automobiles in 200 markets across six continents. With more than Dealers 9,480 dealers 1,515 dealers 1,971 dealers 125 dealers 871 dealers 2,352 dealers 1,376 dealers 6,011 dealers and 280,000 employees and more than 100 plants worldwide, the company’s core and affiliated Markets 116 markets 33 markets 25 markets 27 markets 64 markets 102 markets 138 markets 136 markets automotive brands include Ford, Jaguar, Land Rover, Lincoln, Mercury, Volvo, Aston Martin Retail 5,539,455 130,685 188,579 7,000 74,953 428,780 193,640 1,297,966** and Mazda. The company provides financial services through Ford Motor Credit Company. -

TIBO-2019 Cover ENGL.Indd

• LARGEST ICT FORUM IN BELARUS • NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR COMMUNICATIONS XXVI INTERNATIONAL FORUM ON INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES APRIL 8-12,2019 MINSK, BELARUS REPORT ON XXVI ICT FORUM TIBO-2019 APRIL 8-12, 2019 MINSK, BELARUS CONTENTS CONTENTS Members of the Organizing Committee of Tibo-2019 Forum 4 Welcome speeches to the participants of TIBO-2019 Forum 6 About TIBO-2019 Forum 16 Official opening of the forum and the Plenary Session “Strategy of Digital Transformation” 22 Official opening ceremony of the XXVI International Exhibition on Information and Communication Technologies TIBO-2019 29 Official guests of TIBO-2019 33 Interviews with participants and guests of TIBO-2019 34 Signing the agreements, bilateral meetings 39 II Eurasian Digital Forum 41 Session of the Eurasian Economic Commission “Projects of Digital Agenda for the Eurasian Economic Union” 44 III BELARUSIAN ICT SUMMIT 49 Plenary session “Modern Technological Trends” 51 SECTION A: Broadband access technologies. Cloud technologies 54 SECTION B: Internet of Things technologies. Artificial intelligence 57 SECTION C: Security and protection of information 58 SECTION D: Ways of digital transformation in industry 59 SECTION E: Forum on Internet-security for children 61 SECTION F: Unmanned aerial vehicles 63 SECTION G: Innovative financial technologies 65 IV International Conference “Industry 4.0 – Innovation in the Manufacturing Sector. Industry solutions” 67 IV International Scientific and Practical Conference “SMART LEARNING 2019 – Innovative Technologies in Education” -

ABCD Just Released New Books July 2011

ABCD springer.com Just Released New Books July 2011 All Titles, All Languages Sorted by author and title within the main subject springer.com Architecture & Design 2 Architecture & Design Kunstbank Ferrum - Kulturwerkstätte, Waidhofen / Ybbs, Austria; Niederösterreichische Landesbibliothek, St. Pölten, Austria (Eds.) J. Portugali, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel R. Finsterwalder, Finsterwalderarchitekten, Stephan- skirchen, Germany; W. Wang, Hoidn Wang Partner GbR, Alles eine Frage der Kultur / A Complexity, Cognition and the Berlin, Germany (Eds.) Question of Culture City Álvaro Siza Der Beitrag von Bene zur Entwicklung Complexity, Cognition and the City aims at a deeper Von der Linie zum Raum / From Line to Space eines Architektur- und Designbewusstseins in Österreich und darüber hinaus / The understanding of urbanism, while invoking, on an equal footing, the contributions both the hard and Alvaro Siza gilt als einer der wichtigsten portugiesis- contribution of Bene to the development of chen Architekten des 20. Jahrhunderts. Seine Arbeiten soft sciences have made, and are still making, when architecture and design awareness in Austria werden weit über die Grenzen seines Heimatlandes grappling with the many issues and facets of regional hinaus rezipiert. 1992 erhielt er für sein Lebenswerk and beyond planning and dynamics. In this work, the author den Pritzker-Preis. Sein auf der Museumsinsel Bene Büromöbel, 1790 als Tischlerei in Waidhofen goes beyond merely seeing the city as a self-orga- Hombroich gemeinsam mit Rudolf Finsterwalder an der Ybbs gegründet, generiert in Kooperation nized, emerging pattern of some collective interac- errichtetes Architekturmuseum erfreut sich bei mit bedeutenden ArchitektInnen weltweit neue tion between many stylized urban "agents" – he makes den Besuchern großer Beliebtheit. -

Warranty and Policy Manual

Ford Motor Vehicle Assurance Company Warranty and Policy Manual EDITION: October 2003 Form No. FCS-7755 Warranty & Policy Manual Table of Contents Introduction Page Number Section 1 – Dealership Administration • Responsibility Overview 1-1 • Dealer & Service Supervision Responsibilities 1-7 • Warranty Record Responsibilities 1-10 • Warranty Parts Retention & Return Procedures & Responsibilities 1-17 • Service Technician Specialty Training Standards — ACES II Edits 1-25 • Sublet Invoice Requirements 1-28 Section 2 – Carrier Drop-Off through Delivery to Customer • Carrier Drop-Off Inspection 2-1 • In-Transit Damage/Loss and Damage Repairs 2-12 • Misbuilt/Misinvoiced Vehicles 2-20 • Storage of New Vehicles 2-23 • Pre-delivery/Delivery to Customer 2-25 Section 3 – Warranty Coverages • Coverage Summary/Introduction 3-1 • Ford, Lincoln, Mercury, and TH!NK Car & Light Truck Coverage 3-7 • 600 & Higher Series Truck Coverage 3-53 • Federal Emissions Coverage 3-81 • California Emissions Coverage 3-85 • Battery Coverage 3-93 • Service Part Warranty Coverage 3-109 • Warranty Cancellation - Branded Title 3-127 • Service Contracts (ESP Plans, Superseal, etc.) 3-130 • Ford Remanufactured Parts Coverage/Usage Requirements 3-139 • Governmental Coverage Regulations & Legal Procedures (lemon law, RAV, taxes) 3-141 Section 4 – Recalls, Dealer Self-Approval Guidelines, & After-Warranty Assistance • Safety, Compliance and Emissions Recalls 4-1 • Dealer Self-Approval Guidelines 4-6 • After-Warranty Assistance 4-10 October 2003 Ford Motor Company – Ford Motor -

Ford Motor Company VIN Equipment Codes

Report Abuse « Search: The Web Angelfire Previous | Top 100 | Next » share: del.icio.us | digg | reddit | furl | Ford Excursion+Vin facebook Ads by Google Check Any Vehicle VIN 2010 Ford Official Site Car Search By VIN Number Disc Makers CD Services Vehicle Record Check. Get Unbiased Visit the Official Ford Site Now for the Info You Need At Recession-Proof 1000 CDs in Digipaks now $990! Automotive Information Latest Ford vehicle Info. Prices. Get More, Spend Less! Lowest price, highest quality. www.edmunds.com www.FordVehicles.com www.AutoCheck.com www.discmakers.com/DigipakSale Ford Motor Company VIN Equipment Codes Last updated September 7th, 2005 4th digit 5th digit - line 6th digit - series passenger cars - restraints A minivan trucks active belts plus driver and A20 - Mercury Mountaineer 0 150 series Flareside B A5 - Windstar & Freestar passenger air bags 150 series Styleside & E-Series chassis 1 active belts plus driver and C Econoline F Econoline chassis passenger air bags E-Series cargo van 2 250 series E active belts plus driver and Econoline cargo van 3 350 series H passenger side air bags, F F-series pick-up, regular cab 4 Super Duty series curtains, or canopies M Lincoln & Mercury cars active belts plus driver and K M5 - Mercury Sable sport-utility vehicles passenger air bags M6 - Mercury Mystique M7 - Mercury Grand Marquis & 2 2-door Explorer Mercury Marauder 3 4-door Explorer trucks - Gross Vehicle M81 - Lincoln Town Car Weight Rating (GVWR) M83 - Lincoln Town Car 5 4-door Mountaineer M84 - Lincoln Town Car A 0-3,000 lbs. M85 - Lincoln Town Car B 3,001-4,000 lbs. -

Ford Motor Company One American Road Dearborn, MI 48126 U.S.A

Report Home | Contact | GRI Index | Site Map | Glossary & Key Terms This report is structured according to our Business Principles, which you can access using the colored tabs above. This report is aligned with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) G3 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines released in October 2006, at an application level of A+. See the GRI Index ● Print this report "Welcome to our 2006/7 Sustainability Report. These are challenging times, not only for our Company but for our planet and its inhabitants. The markets for our products are changing rapidly, and there is fierce competition everywhere we operate. Collectively, we face daunting global sustainability ● Download resources challenges, including climate change, depletion of natural resources, poverty, population growth, urbanization and congestion." ● Send feedback Alan Mulally, President and CEO Read the full letter from Bill Ford, Executive Chairman Alan Mulally and Bill Ford Fast track to data: ● Products and Customers ● Vehicle Safety ● Environment ● Quality of Relationships ● Community ● Financial Health ● Workplace Safety Overview Our industry, the business environment and societal expectations continue to evolve, and so does our reporting. Learn about our Company and our vision for sustainability. Our Impacts As a major multinational enterprise, our activities have far-reaching impacts on environmental, social and economic systems. Read about our analysis and prioritization of these issues and impacts. Voices Nine people from inside and outside Ford provide their perspectives on key challenges facing our industry and how Ford is responding, including “new mobility,” good practices in the supply chain and the auto industry’s economic impact. This report was published in June 2007. -

Nanotechnology Publications

Program on Nanotechnology Research and Innovation System Assessment Georgia Institute of Technology Active Nanotechnology: What Can We Expect? A Perspective for Policy from Bibliographical and Bibliometric Analysis Vrishali Subramanian Program in Science, Technology and Innovation Policy School of Public Policy and Enterprise Innovation Institute Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, GA 30332‐0345, USA March 2009 Acknowledgements: This research was undertaken at the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) and at Georgia Tech with support by the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) and Center for Nanotechnology in Society at Arizona State University ( sponsored by the National Science Foundation Award No. 0531194). The findings contained in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN) or the National Science Foundation. For additional details, see http://cns.asu.edu (CNS‐ASU) and http://www.nanopolicy.gatech.edu (Georgia Tech Program on Nanotechnology Research and Innovation Systems Assessment).The author wishes to thank Dave Rejeski, Andrew Maynard, Mihail Roco, Philip Shapira, Jan Youtie and Alan Porter. Executive Summary Over the past few years, policymakers have grappled with the challenge of regulating nanotechnology, whose novelty, complexity and rapid commercialization has highlighted the discrepancies of science and technology oversight. One of the important lessons learned from this experience has been the crucial role of foresight in governing nanotechnology. Active nanostructures are a popular categorization of an emerging class of nanotechnology. The National Science Foundation first solicited “Active Nanostructures and Nanosystems” grants in 2005. Policy reports often refer to greater and different types of risks to society caused by the recently emerging novel applications of nanotechnology, including active nanostructures.