Climate Change, "Everestification,"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The South Face of Dhaulagiri

181 The South Face of Dhaulagiri Franci Savenc Yugoslav alpinists selected the S face of Dhaulagiri (8167m) as a goal some years ago. A request for permission for spring 1982 was submitted as they returned from Everest in 1979. However, in the spring of 1981 approval was received for the post-monsoon period. Although the expedition to the S face of Lhotse had scarcely been concluded, and another was not planned, it was essential to accept the offer. The expedition leader immediately left on a reconnaissance mission and established 2 possibilities: to the left and right of the funnel-shaped central section of the face. After speeded-up preparations, 6 alpinists left on 3 September 1981 for Nepal. Accompanied by Mr Mihan Khadka as liaison officer, five Nepalese staff and 56 porters they left Pokhara on 12 September. The final section of the approach march was over virgin ground. On 23 September they reached the location of Base Camp (3950m), where the low altitude porters left them. Nevertheless by 26 September Base Camp had·been set up. Following a period of bad weather and research, the only acclimatization tour/climb possible was made to Manapanti (6380m) during 1-3 October. From 7-13 October the lower part of the face was explored, the climbers reaching an altitude of 5300m, fixing 400m of rope (grades IV and V) and pitching a tent at 5150m. 15 act.: Stane Belak, Cene Bercic and Emil Tratnik started upon the face and left their tent (5150m) at 0235 the following day. At 0900 they were halted for 7 hours by falling stones at an altitude of 5500m. -

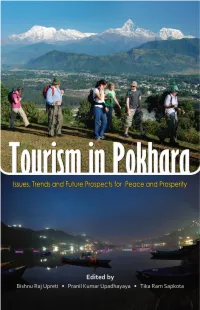

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity

Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity 1 Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity Edited by Bishnu Raj Upreti Pranil Kumar Upadhayaya Tikaram Sapkota Published by Pokhara Tourism Council, Pokhara South Asia Regional Coordination Office of NCCR North-South and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research, Kathmandu Kathmandu 2013 Citation: Upreti BR, Upadhayaya PK, Sapkota T, editors. 2013. Tourism in Pokhara Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity. Kathmandu: Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), South Asia Regional Coordination Office of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North- South) and Nepal Center for Contemporary Research (NCCR), Kathmandu. Copyright © 2013 PTC, NCCR North-South and NCCR, Kathmandu, Nepal All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-9937-2-6169-2 Subsidised price: NPR 390/- Cover concept: Pranil Upadhayaya Layout design: Jyoti Khatiwada Printed at: Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd., Dillibazar, Kathmandu Cover photo design: Tourists at the outskirts of Pokhara with Mt. Annapurna and Machhapuchhre on back (top) and Fewa Lake (down) by Ashess Shakya Disclaimer: The content and materials presented in this book are of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC), the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR North-South) and Nepal Centre for Contemporary Research (NCCR). Dedication To the people who contributed to developing Pokhara as a tourism city and paradise The editors of the book Tourism in Pokhara: Issues, Trends and Future Prospects for Peace and Prosperity acknowledge supports of Pokhara Tourism Council (PTC) and the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, co-funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Journal Vol. LX. No. 2. 2018

JOURNAL OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY VOLUME LX No. 4 2018 THE ASIATIC SOCIETY 1 PARK STREET KOLKATA © The Asiatic Society ISSN 0368-3308 Edited and published by Dr. Satyabrata Chakrabarti General Secretary The Asiatic Society 1 Park Street Kolkata 700 016 Published in February 2019 Printed at Desktop Printers 3A, Garstin Place, 4th Floor Kolkata 700 001 Price : 400 (Complete vol. of four nos.) CONTENTS ARTICLES The East Asian Linguistic Phylum : A Reconstruction Based on Language and Genes George v an Driem ... ... 1 Situating Buddhism in Mithila Region : Presence or Absence ? Nisha Thakur ... ... 39 Another Inscribed Image Dated in the Reign of Vigrahapäla III Rajat Sanyal ... ... 63 A Scottish Watchmaker — Educationist and Bengal Renaissance Saptarshi Mallick ... ... 79 GLEANINGS FROM THE PAST Notes on Charaka Sanhitá Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar ... ... 97 Review on Dr. Mahendra Lal Sircar’s studies on Äyurveda Anjalika Mukhopadhyay ... ... 101 BOOK REVIEW Coin Hoards of the Bengal Sultans 1205-1576 AD from West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam and Bangladesh by Sutapa Sinha Danish Moin ... ... 107 THE EAST ASIAN LINGUISTIC PHYLUM : A RECONSTRUCTION BASED ON LANGUAGE AND GENES GEORGE VAN DRIEM 1. Trans-Himalayan Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, Xiâng, Hokkien, Teochew, Pínghuà, Gàn, Jìn, Wú and a number of other languages and dialects together comprise the Sinitic branch of the Trans-Himalayan language family. These languages all collectively descend from a prehistorical Sinitic language, the earliest reconstructible form of which was called Archaic Chinese by Bernard Karlgren and is currently referred to in the anglophone literature as Old Chinese. Today, Sinitic linguistic diversity is under threat by the advance of Mandarin as a standard language throughout China because Mandarin is gradually taking over domains of language use that were originally conducted primarily in the local Sinitic languages. -

A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya

The Himalaya by the Numbers A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in the Nepal Himalaya Richard Salisbury Elizabeth Hawley September 2007 Cover Photo: Annapurna South Face at sunrise (Richard Salisbury) © Copyright 2007 by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley No portion of this book may be reproduced and/or redistributed without the written permission of the authors. 2 Contents Introduction . .5 Analysis of Climbing Activity . 9 Yearly Activity . 9 Regional Activity . .18 Seasonal Activity . .25 Activity by Age and Gender . 33 Activity by Citizenship . 33 Team Composition . 34 Expedition Results . 36 Ascent Analysis . 41 Ascents by Altitude Range . .41 Popular Peaks by Altitude Range . .43 Ascents by Climbing Season . .46 Ascents by Expedition Years . .50 Ascents by Age Groups . 55 Ascents by Citizenship . 60 Ascents by Gender . 62 Ascents by Team Composition . 66 Average Expedition Duration and Days to Summit . .70 Oxygen and the 8000ers . .76 Death Analysis . 81 Deaths by Peak Altitude Ranges . 81 Deaths on Popular Peaks . 84 Deadliest Peaks for Members . 86 Deadliest Peaks for Hired Personnel . 89 Deaths by Geographical Regions . .92 Deaths by Climbing Season . 93 Altitudes of Death . 96 Causes of Death . 97 Avalanche Deaths . 102 Deaths by Falling . 110 Deaths by Physiological Causes . .116 Deaths by Age Groups . 118 Deaths by Expedition Years . .120 Deaths by Citizenship . 121 Deaths by Gender . 123 Deaths by Team Composition . .125 Major Accidents . .129 Appendix A: Peak Summary . .135 Appendix B: Supplemental Charts and Tables . .147 3 4 Introduction The Himalayan Database, published by the American Alpine Club in 2004, is a compilation of records for all expeditions that have climbed in the Nepal Himalaya. -

In a New and Calm Nepal, the Famed Annapurna Circuit May Soon

LAST RIDE ON THE ANNAPURNA In a new and calm Nepal, the famed Annapurna stone, cold and beautiful. We hang our We’re riding the Annapurna Circuit, prayer flags with the others — symbols of a famous trekking route circling the Circuit may soon become the most incredible desires, dreams, wishes. Then we point our Annapurna Massif in Nepal. It’s normally a mountain-bike touring route in the Himalayas — front wheels downhill. tough 18-day hike that starts in the jungles but at what cost? Nathan Ward rides the fine line And it’s a long downhill, sharp and tech- of the middle hills of Nepal, climbs toward nical, and we ride it all with the befuddled the Tibetan plateau, crosses the high between tradition, legend, and change. brain waves of thin air – jolting through Thorung La, and plummets back to the boulder gardens, slicing into snowdrifts, jungles again. Even though it’s currently t 4:30 a.m., 16,000 feet high in the the sun, the alpine world unfolds before us rolling along perfect sections of singletrack, better suited for feet, we’ve decided to ride Himalayas, the stars shimmer blue in magically like an icy bouquet of high peaks A or just holding on and praying through sec- it on bikes — me, my wife Andrea, and our the cold alpine air. Moon-glow bounces from fanned out across the horizon. We get tions so steep they’re more of a controlled fearless local guide Chandra — to explore a glaciers, wavering, otherworldly, ghostly. on our bikes and pedal shakily up the last slide than a ride. -

DEATH ZONE FREERIDE About the Project

DEATH ZONE FREERIDE About the project We are 3 of Snow Leopards, who commit the hardest anoxic high altitude ascents and perform freeride from the tops of the highest mountains on Earth (8000+). We do professional one of a kind filming on the utmost altitude. THE TRICKIEST MOUNTAINS ON EARTH NO BOTTLED OXYGEN CHALLENGES TO HUMAN AND NATURE NO EXTERIOR SUPPORT 8000ERS FREERIDE FROM THE TOPS MOVIES ALONE WITH NATURE FREERIDE DESCENTS 5 3 SNOW LEOS Why the project is so unique? PROFESSIONAL FILMING IN THE HARDEST CONDITIONS ❖ Higher than 8000+ m ❖ Under challenging efforts ❖ Without bottled oxygen & exterior support ❖ Severe weather conditions OUTDOOR PROJECT-OF-THE-YEAR “CRYSTAL PEAK 2017” AWARD “Death zone freeride” project got the “Crystal Peak 2017” award in “Outdoor project-of-the-year” nomination. It is comparable with “Oscar” award for Russian outdoor sphere. Team ANTON VITALY CARLALBERTO PUGOVKIN LAZO CIMENTI Snow Leopard. Snow Leopard. Leader The first Italian Snow Leopard. MC in mountaineering. Manaslu of “Mountain territory” club. Specializes in a ski mountaineering. freeride 8163m. High altitude Ski-mountaineer. Participant cameraman. of more than 20 high altitude expeditions. Mountains of the project Manaslu Annapurna Nanga–Parbat Everest K2 8163m 8091m 8125m 8848m 8611m The highest mountains on Earth ❖ 8027 m Shishapangma ❖ 8167 m Dhaulagiri I ❖ 8035 m Gasherbrum II (K4) ❖ 8201 m Cho Oyu ❖ 8051 m Broad Peak (K3) ❖ 8485 m Makalu ❖ 8080 m Gasherbrum I (Hidden Peak, K5) ❖ 8516 m Lhotse ❖ 8091 m Annapurna ❖ 8586 m Kangchenjunga ❖ 8126 m Nanga–Parbat ❖ 8614 m Chogo Ri (K2) ❖ 8156 m Manaslu ❖ 8848 m Chomolungma (Everest) Mountains that we climbed on MANASLU September 2017 The first and unique freeride descent from the altitude 8000+ meters among Russian sportsmen. -

Mizoram Tops List CONTENTS

Mizoram Tops List CONTENTS S. No. Chapter Name Page No. 1. United Nations 75th Anniversary 1-2 2. International and Bilateral 3-4 3. National 5-9 4. States 10-11 5. Economy and Banking 12-16 6. RBI Updates 17-18 7. Schemes 19-20 8. Cabinet Approvals 21 9. Science and Technology 22-23 10. Defence 24-25 11 Bills And Acts 26-28 12. Awards and Honours 29-31 13. Sports 32-33 14. Persons In News 34 15. Obituaries 35-36 16. Reports, Indices and Ranking 37-38 17. Committees 39 18. Summits and Conferences 40 19. Appointments 41 20. Days And Themes 42 21. Books and Authors 43 22. Brand Ambassadors 43 23. Practice Bits (Current Affairs) 44-55 Current Affairs October 2020– Digest 1. UNITED NATIONS 75TH ANNIVERSARY On September 21, 2020 a “Declaration on the New York and under the Presidency of Volkan Commemoration of the 75th Anniversary of the Bozkir of Turkey. United Nations” was adopted at the high level For this session the world leaders submitted pre- meeting for strengthening mechanism to combat recorded video statements which were played in the terrorism, reformed multilateralism, inclusive General Assembly Hall during the general debate development and better preparedness to deal with held from Sept 22-29 at the beginning of each session of the General Assembly. challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. As a part of From India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi declaration the 193 member nations commit to leave addressed the high-level meeting to mark the 75th no one behind, protect the planet, promote peace and anniversary of the UN on September 22 and the prevent conflicts, abide by international law and general debate on September 26 through the pre- ensure justice, place women and girls at the centre, recorded video statements. -

Nepal 1982 Letter from Kathmandu

199 Nepal 1982 Letter from Kathmandu Mike Cheney Post-Monsoon, 1981 Of the 42 expeditions which arrived in Nepal for the post-monsoon season, 17 were successful and 25 unsuccessful. The weather right across the Nepal Himal was exceptionally fine during the whole ofOctober and November with the exception of the first week in November, when a cyclone in western India brought rain and snow for 2 or 3 days. As traditionally happens, the Monsoon finished right on time with a major downpour of rain on 28 September. The worst of the storm was centred over a fairly small part of Central Nepal, the area immediately south of the Annapurna range. The heavy snowfalls caused 6 deaths (2 Sherpas, 2 Japanese and 2 French) on Annapurna Himal expeditions, over 200 other Nepalis also died, and many more lost their homes and all their possessions-the losses on expeditions were small indeed compared with those of the Hill and Terai peoples. Four other expedition members died as a result of accidents-2 Japanese and 2 Swiss. Winter season, 1981/82 There were four foreign expeditions during the winter climbing season, which is December and January in Nepal. Two expeditions were on Makalu-one British expedition of 6 members, led by Ron Rutland, and one French. In addition there was an American expedition to Pumori and a Canadian expedition to Annapurna IV. The American expedition to Pumori was successful. Pre-Monsoon, 1982 This was one of the most successful seasons for many years. Of the 28 expeditions attempting 26 peaks-there were 2 expeditions on Kanchenjunga and 2 on Lamjung-21 were successful. -

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy Andactionplan2016-2025|Chitwan-Annapurnalandscape,Nepal

Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Strategy andActionPlan2016-2025|Chitwan-AnnapurnaLandscape,Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1- 4211567, 4211936 Fax: +977-1-4223868 Website: www.mfsc.gov.np Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025 Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Publisher: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Citation: Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation 2015. Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2025, Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape, Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu, Nepal Cover photo credits: Forest, River, Women in Community and Rhino © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Snow leopard © WWF Nepal/ DNPWC Rhododendron © WWF Nepal Back cover photo credits: Forest, Gharial, Peacock © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Nabin Baral Red Panda © Kamal Thapa/ WWF Nepal Buckwheat fi eld in Ghami village, Mustang © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kapil Khanal Women in wetland © WWF Nepal, Hariyo Ban Program/ Kashish Das Shrestha © Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Acronyms and Abbreviations ACA Annapurna Conservation Area asl Above Sea Level BZ Buffer Zone BZUC Buffer Zone User Committee CA Conservation Area CAMC Conservation Area Management Committee CAPA Community Adaptation Plans for Action CBO Community Based Organization CBS -

Annapurna Circuit

ANNAPURNA CIRCUIT COUNTRIES VISITED: NEPAL TRIP TYPE: Trekking TRIP LEADER: Local Leader TRIP GRADE: Strenuous GROUP SIZE: 2 - 10 people TRIP STYLE: Tea House NEXT DEPARTURE: 03 Apr 2022 NAN Based On 0 Reviews 32 Trees Planted for each Booking KG Carbon Footprint This is the classic Annapurna Circuit trek crossing the high pass of Thorong La at 5,416m. On this Annapurna trek we follow the Kali Gandaki valley then ascend to the viewpoint at Poon Hill. Trekking Annapurna Circuit offers a cross section of Nepal Himalaya. The mountain views throughout encompass some of the highest peaks in the world. They include Lamjung, Himalchuli, Manaslu, Dhaulagiri, Annapurna and Machapuchare. The Annapurna Circuit walk starts several hours driving beyond Besishar town at the village of Jagat. You hike through Gurung villages surrounded by terraced fields in Marsyangdi valley. The trail enters pine forest and higher up into the alpine zone around Annapurna. There has been debate about the recent road construction in the Annapurna region. It is still worth trekking the Annapurna Circuit trek as it is possible to avoid walking on the road. By hiking on alternative trails you will enjoy the experience on this classic trek. We follow Natural Annapurna Trekking Trails (NATT) where possible. We organised a recce trek following NATT for outdoor journalist, Terry Adby. Take a look at his article "The Return of the Annapurnas". in online magazine Outdoor Enthusiast starting on Page 46. Also see BMC The New Way: Trekking Nepal’s Annapurnas. www.themountaincompany.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1647 433880 After Pisang village we enter a Buddhist region. -

Overview Itinerary Details

Annapurna Circuit Trekking Overview There are very less trekking itineraries in Nepal which command as much attention of the visiting tourists as does the Annapurna Circuit Trekking. The popular trekking route of Annapurna Circuit lies in the Western part of the country, nearby from the popular tourist town of Pokhara. No wonder, Annapurna Sanctuary Trekking is a wonderful opportunity for the visiting tourists to learn and explore more about the fascinating region of Annapurna which is popular both inside and outside the country. It is by far the most amazing and popular trekking destination in the Annapurna region of Nepal. Annapurna region is crowded throughout the year as the visiting tourists come here to enjoy the adventures of Nepal trek and also to enjoy the natural sightseeing in the famous region. Annapurna Circuit Trekking with the ‘Nepal Glacier Treks’ is a 21-day trekking itinerary during the course of which the visiting tourists can witness the beauty of the Annapurna region, enjoy trekking in Nepal, and also observe the greatness of the popular Thorong-La Pass while also get the chance to visit the holy shrine of Muktinath. The shrine of Muktinath is a major highlight of the circuit trekking as many domestic tourists come here for pilgrimage purpose as well. The Hindu temple of Muktinath is located at around 3700 meters of altitude. The valley of Manang and the places like Jomsom are other major attractions of the Annapurna Circuit Trekking. The maximum elevation which the trekkers reach during Circuit trekking will be around 5400 meters, while the months of September- November and March-May are best for the trekking.