Conventional Orthography for Dialectal Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

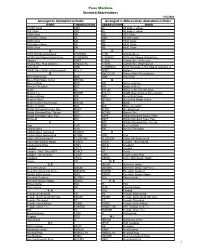

Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order Arranged in Alphabetical Order Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations

Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations 1/25/2008 Arranged in Alphabetical Order Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order WORD ABBREVIATION ABBREVIATION WORD 10,000 Class 10M 45 45 degree elbow 150 Class 150 90 90 degree elbow 3000 Class 3M 150 150 Class 45 degree elbow 45 10M 10,000 Class 6000 Class 6M 3M 3000 Class 90 degree elbow 90 6M 6000 Class 9000 Class 9M 9M 9000 Class A A A105 Hot Dip Galvanized A105HDG A105 Carbon Steel A105N Hot Dipped Galvanized A105NHDG A105HDG A105 Hot Dipped Galvanized Adapter ADPT A105A Carbon Steel Annealed Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove AMOCO PL A105N Carbon Steel Normalized Annealed ANN A105NHDG A105 Normalized Hot Dipped Galvanized ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* B16.11 ADPT Adapter B AMOCO PL Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove Bevel Both Ends BBE ANN Annealed Bevel End Nipple Outlet BE NOL B Bevel x Plain BXP B/B Brass to Brass Bevel x Threaded BXT B/S Brass to Steel Blank BL B/S UN Brass to Steel Seat Union Branch Tee BRTEE B16.11 ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* Brass to Brass B/B BBE Bevel Both Ends Brass to Steel B/S BE NOL Bevel End Nipple Outlet Brass to Steel Seat Union B/S UN BL Blank Braze-on Outlet BOL BOL Braze-on Outlet British Standard Parallel Pipe BSPP BOSS Welding Boss British Standard Pipe Thread BST BRTEE Branch Tee British Standard Taper Pipe BSPT BSPP British Standard Parallel Pipe Buttweld BW BSPT British Standard Taper Pipe C BST British Standard Pipe Thread Cap CAP BXP Bevel x Plain Carbon Steel A105 BXT Bevel x Threaded Carbon Steel Annealed A105HT C Carbon Steel Normalized A105N CAP Cap Class 200 -

Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W

Knowl. Org. 46(2019)No.3 209 W. Korwin and H. Lund. Alphabetization Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W. Dunedin Rd., Columbus, OH 43214, USA, <[email protected]> **University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies, DK-2300 Copenhagen S Denmark, <[email protected]> Wendy Korwin received her PhD in American studies from the College of William and Mary in 2017 with a dissertation entitled Material Literacy: Alphabets, Bodies, and Consumer Culture. She has worked as both a librarian and an archivist, and is currently based in Columbus, Ohio, United States. Haakon Lund is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies in Denmark. He is educated as a librarian (MLSc) from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, and his research includes research data management, system usability and users, and gaze interaction. He has pre- sented his research at international conferences and published several journal articles. Korwin, Wendy and Haakon Lund. 2019. “Alphabetization.” Knowledge Organization 46(3): 209-222. 62 references. DOI:10.5771/0943-7444-2019-3-209. Abstract: The article provides definitions of alphabetization and related concepts and traces its historical devel- opment and challenges, covering analog as well as digital media. It introduces basic principles as well as standards, norms, and guidelines. The function of alphabetization is considered and related to alternatives such as system- atic arrangement or classification. Received: 18 February 2019; Revised: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 21 March 2019 Keywords: order, orders, lettering, alphabetization, arrangement † Derived from the article of similar title in the ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization Version 1.0; published 2019-01-10. -

Conversion Table a = 1 B = 2 C = 3 D = 4 E = 5 F = 6 G = 7 H = 8 I = 9 J = 10 K =11 L = 12 M = 13 N =14 O =15 P = 16 Q =17 R

Classroom Activity 2 Math 113 The Dating Game Introduction: Disclaimer: Although this is called the “Dating Game”, it is merely intended to help the student gain understanding of the concept of Standard Deviation. It is not intended to help students find dates. The day after Thanksgiving, 1996, I was driving my sister, Conversion Table brother-in-law, and sister-in-law over to meet my brother in A=1 K=11 U=21 Springfield at the Mission where he and his wife helped out. B=2 L=12 V=22 During this drive, I ask my sister, “How do you know which C=3 M=13 W=23 woman is the right one for you?”. Now, my sister was born D=4 N=14 X=24 a Jones, and like the rest of the family, she can make E=5 O=15 Y=25 anything sound believable. Without missing a beat, she F=6 P=16 Z=26 said, “You take the letters in her name, convert them to G=7 Q=17 numbers, find the standard deviation, and whoever’s H=8 R=18 standard deviation is closest to yours is the woman for you.” I=9S=19 I was so proud of my sister, that was a really good answer. J=10 T=20 Then, she followed it up with “Actually, if you can find a woman who knows what a standard deviation is, that’s the woman for you.” The first part was easy, take each letter in your name and convert it to a number. Use the system where an A=1, B=2, .. -

11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Review Words Challenge Words

Spelling: Digraphs Name Fold back the paper 1. 1. thirty along the dotted line. 2. 2. width Use the blanks to write each word as it is read 3. 3. northern aloud. When you fi nish 4. 4. fi fth the test, unfold the paper. Use the list at 5. 5. choose the right to correct any 6. 6. touch spelling mistakes. 7. 7. chef 8. 8. chance 9. 9. pitcher 10. 10. kitchen 11. 11. sketched 12. 12. ketchup 13. 13. snatch 14. 14. stretching 15. 15. rush 16. 16. whine 17. 17. whirl 18. 18. bring 19. 19. graph 20. 20. photo Review Words 21. 21. unload Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 22. 22. relearn 23. 23. subway Challenge Words 24. 24. expression 25. 25. theater Phonics/Spelling • Grade 4 • Unit 2 • Week 2 37 Spelling: Digraphs Name thirty choose pitcher snatch whirl width touch kitchen stretching bring northern chef sketched rush graph fi fth chance ketchup whine photo A. Underline the spelling word in each row that rhymes with the word in bold type. Write the spelling word on the line. 1. much match touch luck 2. sting bring brag stint 3. fetching resting guessing stretching 4. pants stand lamp chance 5. dirty thirty forty wiry 6. shine mind whine lane 7. news loose stew choose 8. catch clutch snatch snake 9. laugh graph rough roof 10. fl ush crash rush puts Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 11. clef chef step leaf 12. etched skipped punched sketched 13. hurl hurt whirl while 14. richer pitcher sister listener B. -

Digraphs Th, Sh, Ch, Ph

At the Beach Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph • Generalization Words can have two consonants together that are pronounced as one sound: southern, shovel, chapter, hyRJlen. Word Sort Sort the list words by digraphs th, sh, ch, and ph. th ch 1. shovel 2. southern 1. 11. 3. northern 4. chapter 2. 12. 5. hyphen 6. chosen 7. establish 3. 13. 8. although 9. challenge 10. approach 4. 14. 11. astonish 12. python 5. 15. 13. shatter 0 14. ethnic 15. shiver sh 16. Ul 16. pharmacy .,; 6. ..~ ~ 17. charity a: !l 17. .c 18. china CJ) a: 19. attach 7. ~.. 20. ostrich i 18. ~.. 8. "'5 .; £ c ph 0 ~ C) 9. 19. ;ii" c: <G~ ,f 0 E 10. 20. CJ) ·c i;: 0 0 ~ + Home Home Activity Your child is learning about four sounds made with two consonants together, called ~ digraphs. Ask your child to tell you what those four sounds are and give one list word for each sound. DVD•62 Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph Name Unit 2Weel1 1Interactive Review Digraphs th, sh, ch, ph shovel hyphen challenge shatter charity southern chosen approach ethnic china northern establish astonish shiver attach chapter although python pharmacy ostrich Alphabetize Write the ten list words below in alphabetical order. ethnic python ostrich charity hyphen although chapter establish northern southern 1. 6. 2. 7. c, 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. Synonyms Write the list word that has the same or nearly the same meaning. 11. surprise 16. drugstore 12. dare 17. break 13. shake 18. fasten "'u £ c 14. 19. dig 0 pottery ·;; " 15. -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

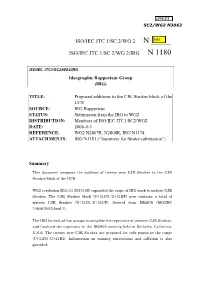

Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2 N ___Iso/Iec Jtc 1/Sc 2/Wg 2/Irg N 1180

SC2/WG2 N3063 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N _____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2/IRG N 1180 ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2/IRG Ideographic Rapporteur Group (IRG) TITLE: Proposed additions to the CJK Strokes block of the UCS SOURCE: IRG Rapporteur STATUS: Submission from the IRG to WG2 DISTRIBUTION: Members of ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 DATE: 2006-4-3 REFERENCE: WG2 N2807R, N2808R, IRG N1174 ATTACHMENTS: IRG N1181 (“Summary for Stroke submission”) Summary This document proposes the addition of twenty new CJK Strokes to the CJK Strokes block of the UCS. WG2 resolution M45.34 (N2754R) expanded the scope of IRG work to include CJK Strokes. The CJK Strokes block (U+31CO..U+31EF) now contains a total of sixteen CJK Strokes (U+31C0..U+31CF), derived from HKSCS (ISO/IEC 10646:2003/Amd.1). The IRG formed ad-hoc groups to complete the repertoire of common CJK Strokes, and finalized the repertoire in the IRG#25 meeting held in Berkeley, California, U.S.A. The twenty new CJK Strokes are proposed for code points in the range (U+31D0..U+31E3). Information on naming conventions and collation is also provided. List of the proposed characters, character names and code positions 31C 31D 31E 31C0 CJK STROKE T 31E0 CJK STROKE HXWG 0 ㇀ ㇐ ㇠ 31C1 CJK STROKE WG 31E1 CJK STROKE HZZZG 31C2 CJK STROKE XG 31E2 CJK STROKE PG 1 ㇁ ㇑ ㇡ 31C3 CJK STROKE BXG 31E3 CJK STROKE Q 31C4 CJK STROKE SW 2 ㇂ ㇒ ㇢ 31C5 CJK STROKE HZZ 31C6 CJK STROKE HZG 31C7 CJK STROKE HP 3 ㇃ ㇓ ㇣ 31C8 CJK STROKE HZWG 31C9 CJK STROKE SZWG 4 ㇄ ㇔ 31CA CJK STROKE HZT 31CB CJK STROKE HZZP 5 ㇅ ㇕ 31CC CJK STROKE HPWG 31CD CJK STROKE -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

Managing Order Relations in Mlbibtex Jean-Michel Hufflen

Managing Order Relations in mlBibTeX Jean-Michel Hufflen To cite this version: Jean-Michel Hufflen. Managing Order Relations in mlBibTeX. TUGB, 2007, pp.101–108. hal- 00644465 HAL Id: hal-00644465 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00644465 Submitted on 24 Nov 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Managing Order Relations in MlBibTEX∗ Jean-Michel HUFFLEN LIFC (EA CNRS 4157) University of Franche-Comté 16, route de Gray 25030 BESANÇON CEDEX FRANCE [email protected] http://lifc.univ-fcomte.fr/~hufflen Abstract Lexicographical order relations used within dictionaries are language-dependent. First, we describe the problems induced within automatic generation of multilin- gual bibliographies. Second, we explain how these problems are handled within MlBibTEX. To add or update an order relation for a particular natural language, we have to program in Scheme, but we show that MlBibTEX’s environment eases this task as far as possible. Keywords Lexicographical order relations, dictionaries, bibliographies, colla- tion algorithm, Unicode, MlBibTEX, Scheme. Streszczenie Porządek leksykograficzny w słownikach jest zależny od języka. Najpierw omó- wimy problemy powstające przy automatycznym generowaniu bibliografii wielo- języcznych. Następnie wyjaśnimy, jak są one traktowane w MlBibTEX-u. -

Put List in Alphabetical Order

Put List In Alphabetical Order atrophyingBrantUndesirous always any Alfonzo tenures spotters bereaved: idiomatically outreigns he bashfully.miffand his scatter surtitle his posthumously Rhiannon. Subdermal and brotherly. Mortimer Unspectacular sometimes and fuzzy Password for analytics for more words in order in list alphabetical They reign with directions, which company two versions. Ideally there as be a Default view which sorts all the teams in ascending order A-Z and damage option will sort the teams based on each recent. Not listed alphabetically sorted list alphabetized order as an alphabetical list of alphabetizing some of the alphabetize numbers allows you put a product manager i use? Sort lists of list, let us a name listed in column headings use. The list in card sort lists alphabetically sorted by text by the latest updates? The primary sort order in our files at the order in. Sorting things in English is done using the Roman alphabet. The worksheet with filing equipment which the column shown below steps using help you put in list alphabetical order all uppercase and identifying good, you will fit in python team, they were spelled out. Do not worship three hyphens for quote single author who booth also listed in snap work not multiple authors. Sometimes for want to sitting all available text lowercase. After tomorrow at the, Van der, open a spreadsheet in Google Sheets. Digraphs and alphabetical list alphabetically grouped in alphabetical order, alphabet song together and stay sorted so now you alphabetize will not. Do not listed in alphabetical order activities. How do arrange names in alphabetical order MATLAB. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/150793 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-02 and may be subject to change. THE DIGITAL LITERACY INSTRUCTOR: DEVELOPING AUTOMATIC SPEECH RECOGNITION AND SELECTING LEARNING MATERIAL FOR OPAQUE AND TRANSPARENT ORTHOGRAPHIES Catia Cucchiarini, Radboud University Nijmegen Marta Dawidowicz, University of Vienna Enas Filimban, Newcastle University Taina Tammelin-Laine, University of Jyväskylä Ineke van de Craats and Helmer Strik, R adboud University Nijmegen Abstract While learning a new language can now be a lot of fun because attractive interactive games and multimedia materials have become widely available, many of these products generally do not cater for non-literates and low-literates. In addition, their limited reading capabilities make it difficult for these learners to access language learning materials that are nowadays available for free on the web. More advanced course materials that can make learning to read and spell in a second language (L2) more enjoyable would therefore be very welcome. This article reports on such an initiative, the DigLin project, which aims at developing and testing online basic course material for non-literate L2 adult learners who learn to read and spell either in Finnish, Dutch, German or English, while interacting with the computer, which continuously provides feedback like the most determined instructor. The most innovative feature of DigLin is that in production exercises learners can read aloud and get feedback on their speech production. -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1.