17Th Century Estonian Orthography Reform, the Teaching of Reading and the History of Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survey of Orthographic Information in Machine Translation 3

Machine Translation Journal manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) A Survey of Orthographic Information in Machine Translation Bharathi Raja Chakravarthi1 ⋅ Priya Rani 1 ⋅ Mihael Arcan2 ⋅ John P. McCrae 1 the date of receipt and acceptance should be inserted later Abstract Machine translation is one of the applications of natural language process- ing which has been explored in different languages. Recently researchers started pay- ing attention towards machine translation for resource-poor languages and closely related languages. A widespread and underlying problem for these machine transla- tion systems is the variation in orthographic conventions which causes many issues to traditional approaches. Two languages written in two different orthographies are not easily comparable, but orthographic information can also be used to improve the machine translation system. This article offers a survey of research regarding orthog- raphy’s influence on machine translation of under-resourced languages. It introduces under-resourced languages in terms of machine translation and how orthographic in- formation can be utilised to improve machine translation. We describe previous work in this area, discussing what underlying assumptions were made, and showing how orthographic knowledge improves the performance of machine translation of under- resourced languages. We discuss different types of machine translation and demon- strate a recent trend that seeks to link orthographic information with well-established machine translation methods. Considerable attention is given to current efforts of cog- nates information at different levels of machine translation and the lessons that can Bharathi Raja Chakravarthi [email protected] Priya Rani [email protected] Mihael Arcan [email protected] John P. -

Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names

ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division Technical reference manual for the standardization of geographical names United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names United Nations New York, 2007 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of material in the present publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term “country” as used in the text of this publication also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.M/87 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. -

Methods for Estonian Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition

THESIS ON INFORMATICS AND SYSTEM ENGINEERING C Methods for Estonian Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition TANEL ALUMAE¨ Faculty of Information Technology Department of Informatics TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Dissertation was accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering on November 1, 2006. Supervisors: Prof. Emer. Leo Vohandu,˜ Faculty of Information Technology Einar Meister, Ph.D., Institute of Cybernetics at Tallinn University of Technology Opponents: Mikko Kurimo, Dr. Tech., Helsinki University of Technology Heiki-Jaan Kaalep, Ph.D., University of Tartu Commencement: December 5, 2006 Declaration: Hereby I declare that this doctoral thesis, my original investigation and achievement, submitted for the doctoral degree at Tallinn University of Technology has not been submitted for any degree or examination. / Tanel Alumae¨ / Copyright Tanel Alumae,¨ 2006 ISSN 1406-4731 ISBN 9985-59-661-7 ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The speech recognition problem . 1 1.2 Language specific aspects of speech recognition . 3 1.3 Related work . 5 1.4 Scope of the thesis . 6 1.5 Outline of the thesis . 7 1.6 Acknowledgements . 7 2 Basic concepts of speech recognition 9 2.1 Probabilistic decoding problem . 10 2.2 Feature extraction . 10 2.2.1 Signal acquisition . 11 2.2.2 Short-term analysis . 11 2.3 Acoustic modelling . 14 2.3.1 Hidden Markov models . 15 2.3.2 Selection of basic units . 20 2.3.3 Clustered context-dependent acoustic units . 20 2.4 Language Modelling . 22 2.4.1 N-gram language models . 23 2.4.2 Language model evaluation . 29 3 Properties of the Estonian language 33 3.1 Phonology . -

Finnish Inserted Vowels: a Case of Phonologized Excrescence

Nordic Journal of Linguistics (2021), page 1 of 31 doi:10.1017/S033258652100007X ARTICLE Finnish inserted vowels: a case of phonologized excrescence Robin Karlin University of Wisconsin-Madison, Waisman Center, Madison, WI, 53705, USA Email for correspondence: [email protected] (Received 12 March 2019; revised 1 September 2020; accepted 10 December 2020) Abstract In this paper, I examine a case of vowel insertion found in Savo and Pohjanmaa dialects of Finnish that is typically called “epenthesis”, but which demonstrates characteristics of both phonetic excrescence and phonological epenthesis. Based on a phonological analysis paired with an acoustic corpus study, I argue that Finnish vowel insertion is the mixed result of phonetic excrescence and the phonologization of these vowels, and is related to second-mora lengthening, another dialectal phenomenon. I propose a gestural model of second-mora lengthening that would generate vowel insertion in its original phonetic state. The link to second-mora lengthening provides a unified account that addresses both the dialectal and phonological distribution of the phenomenon, which have not been linked in previous literature. Keywords: excrescence; epenthesis; Finnish; gestures; phonetics; phonology 1. Introduction In this paper, I examine a case of vowel insertion found in Savo and Pohjanmaa dialects of Finnish that has typically been analyzed as a phonological repair, but which demonstrates characteristics of both phonetic excrescence and phonological epenthesis. Using both acoustic data and a phonological analysis of the distribution, I argue that Finnish vowel insertion originated as a phonetic intrusion, but then became phonologized over time. I follow Hall (2006) in assuming that excrescent vowels are the result of gestural underlap, and argue that the original gestural underlap was caused by second-mora lengthening, another phenomenon present in these dialects. -

VALTS ERNÇSTREITS (Riga) LIVONIAN ORTHOGRAPHY Introduction the Livonian Language Has Been Extensively Written for About

Linguistica Uralica XLIII 2007 1 VALTS ERNÇSTREITS (Riga) LIVONIAN ORTHOGRAPHY Abstract. This article deals with the development of Livonian written language and the related matters starting from the publication of first Livonian books until present day. In total four different spelling systems have been used in Livonian publications. The first books in Livonian appeared in 1863 using phonetic transcription. In 1880, the Gospel of Matthew was published in Eastern and Western Livonian dialects and used Gothic script and a spelling system similar to old Latvian orthography. In 1920, an East Livonian written standard was established by the simplification of the Finno-Ugric phonetic transcription. Later, elements of Latvian orthography, and after 1931 also West Livonian characteristics, were added. Starting from the 1970s and due to a considerable decrease in the number of Livonian mother tongue speakers in the second half of the 20th century the orthography was modified to be even more phonetic in the interest of those who did not speak the language. Additionally, in the 1930s, a spelling system which was better suited for conveying certain phonetic phenomena than the usual standard was used in two books but did not find any wider usage. Keywords: Livonian, standard language, orthography. Introduction The Livonian language has been extensively written for about 150 years by linguists who have been noting down examples of the language as well as the Livonians themselves when publishing different materials. The prime consideration for both of these groups has been how to best represent the Livonian language in the written form. The area of interest for the linguists has been the written representation of the language with maximal phonetic precision. -

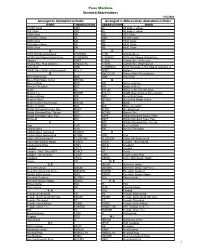

Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order Arranged in Alphabetical Order Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations

Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations 1/25/2008 Arranged in Alphabetical Order Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order WORD ABBREVIATION ABBREVIATION WORD 10,000 Class 10M 45 45 degree elbow 150 Class 150 90 90 degree elbow 3000 Class 3M 150 150 Class 45 degree elbow 45 10M 10,000 Class 6000 Class 6M 3M 3000 Class 90 degree elbow 90 6M 6000 Class 9000 Class 9M 9M 9000 Class A A A105 Hot Dip Galvanized A105HDG A105 Carbon Steel A105N Hot Dipped Galvanized A105NHDG A105HDG A105 Hot Dipped Galvanized Adapter ADPT A105A Carbon Steel Annealed Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove AMOCO PL A105N Carbon Steel Normalized Annealed ANN A105NHDG A105 Normalized Hot Dipped Galvanized ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* B16.11 ADPT Adapter B AMOCO PL Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove Bevel Both Ends BBE ANN Annealed Bevel End Nipple Outlet BE NOL B Bevel x Plain BXP B/B Brass to Brass Bevel x Threaded BXT B/S Brass to Steel Blank BL B/S UN Brass to Steel Seat Union Branch Tee BRTEE B16.11 ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* Brass to Brass B/B BBE Bevel Both Ends Brass to Steel B/S BE NOL Bevel End Nipple Outlet Brass to Steel Seat Union B/S UN BL Blank Braze-on Outlet BOL BOL Braze-on Outlet British Standard Parallel Pipe BSPP BOSS Welding Boss British Standard Pipe Thread BST BRTEE Branch Tee British Standard Taper Pipe BSPT BSPP British Standard Parallel Pipe Buttweld BW BSPT British Standard Taper Pipe C BST British Standard Pipe Thread Cap CAP BXP Bevel x Plain Carbon Steel A105 BXT Bevel x Threaded Carbon Steel Annealed A105HT C Carbon Steel Normalized A105N CAP Cap Class 200 -

Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W

Knowl. Org. 46(2019)No.3 209 W. Korwin and H. Lund. Alphabetization Alphabetization† †† Wendy Korwin*, Haakon Lund** *119 W. Dunedin Rd., Columbus, OH 43214, USA, <[email protected]> **University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies, DK-2300 Copenhagen S Denmark, <[email protected]> Wendy Korwin received her PhD in American studies from the College of William and Mary in 2017 with a dissertation entitled Material Literacy: Alphabets, Bodies, and Consumer Culture. She has worked as both a librarian and an archivist, and is currently based in Columbus, Ohio, United States. Haakon Lund is Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Information Studies in Denmark. He is educated as a librarian (MLSc) from the Royal School of Library and Information Science, and his research includes research data management, system usability and users, and gaze interaction. He has pre- sented his research at international conferences and published several journal articles. Korwin, Wendy and Haakon Lund. 2019. “Alphabetization.” Knowledge Organization 46(3): 209-222. 62 references. DOI:10.5771/0943-7444-2019-3-209. Abstract: The article provides definitions of alphabetization and related concepts and traces its historical devel- opment and challenges, covering analog as well as digital media. It introduces basic principles as well as standards, norms, and guidelines. The function of alphabetization is considered and related to alternatives such as system- atic arrangement or classification. Received: 18 February 2019; Revised: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 21 March 2019 Keywords: order, orders, lettering, alphabetization, arrangement † Derived from the article of similar title in the ISKO Encyclopedia of Knowledge Organization Version 1.0; published 2019-01-10. -

Reading Development in Two

Psychologica Belgica 2009, 49-2&3, 111-156. READING DEVELOPMENT IN TWO ALPHABETIC SYSTEMS DIFFERING IN ORTHOGRAPHIC CONSISTENCY: A LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF FRENCH-SPEAKING CHILDREN ENROLLED IN A DUTCH IMMERSION PROGRAM Katia LECOCQ, Régine KOLINSKY, Vincent GOETRY, José MORAIS, Jesus ALEGRIA, & Philippe MOUSTY Université Libre de Bruxelles Studies examining reading development in bilinguals have led to conflicting conclusions regarding the language in which reading development should take place first. Whereas some studies suggest that reading instruction should take place in the most proficient language first, other studies suggest that reading acquisition should take place in the most consistent orthographic system first. The present study examined two research questions: (1) the relative impact of oral proficiency and orthographic transparency in second-language reading acquisition, and (2) the influence of reading acquisition in one language on the development of reading skills in the other language. To examine these questions, we compared reading development in French- native children attending a Dutch immersion program and learning to read either in Dutch first (most consistent orthography) or in French first (least consistent orthography but native language). Following a longitudinal design, the data were gathered over different sessions spanning from Grade 1 to Grade 3. The children in immersion were presented with a series of experi- mental and standardised tasks examining their levels of oral proficiency as well as their reading abilities in their first and, subsequently in their second, languages of reading instruction. Their performances were compared to the ones of French and Dutch monolinguals. The results showed that by the end of Grade 2, the children instructed to read in Dutch first read in both languages as well as their monolingual peers. -

COME JOIN US We Here at the N.C

2014 OUR COAST COME JOIN US WWW.NCCOAST.ORG We here at the N.C. Coastal Federation don’t view our coast as a museum artifact under glass — something to be viewed but not touched. It’s far too important for that. We want people to enjoy the beauty of our these places we love remain for those who used, and most importantly, to be protected coast, the way we do. We want you to join us — come after us. and restored. to marvel at its magnificent sunsets, to eat the This Our Coast offers a few ways to do this. The philosophy behind Our Coast is simple. bounty that its waters provide. We want you to Yes, it’s a travel guide of sorts, but it’s not like We believe the more you cherish and use our paddle down a quiet river, boat out to offshore the dozens of others that you can pick up this coast, the more invested you become in helping fishing grounds or hike through a stately summer in stands from Corolla to Calabash. We us keep it healthy and spectacular. Our work longleaf pine forest, looking for birds, alligators like to call it a travel guide with a conscience. provides great opportunities for you to help or even a bear. We also want people to make Our Coast is about some of the most our coast, and if you agree, we hope you’ll jump their livings off our coast. dynamic, productive and beautiful places aboard and join us in our efforts. But we hope that we will all do these things on earth that are not far from where you responsibly, in ways that don’t threaten our are probably reading this today. -

Conversion Table a = 1 B = 2 C = 3 D = 4 E = 5 F = 6 G = 7 H = 8 I = 9 J = 10 K =11 L = 12 M = 13 N =14 O =15 P = 16 Q =17 R

Classroom Activity 2 Math 113 The Dating Game Introduction: Disclaimer: Although this is called the “Dating Game”, it is merely intended to help the student gain understanding of the concept of Standard Deviation. It is not intended to help students find dates. The day after Thanksgiving, 1996, I was driving my sister, Conversion Table brother-in-law, and sister-in-law over to meet my brother in A=1 K=11 U=21 Springfield at the Mission where he and his wife helped out. B=2 L=12 V=22 During this drive, I ask my sister, “How do you know which C=3 M=13 W=23 woman is the right one for you?”. Now, my sister was born D=4 N=14 X=24 a Jones, and like the rest of the family, she can make E=5 O=15 Y=25 anything sound believable. Without missing a beat, she F=6 P=16 Z=26 said, “You take the letters in her name, convert them to G=7 Q=17 numbers, find the standard deviation, and whoever’s H=8 R=18 standard deviation is closest to yours is the woman for you.” I=9S=19 I was so proud of my sister, that was a really good answer. J=10 T=20 Then, she followed it up with “Actually, if you can find a woman who knows what a standard deviation is, that’s the woman for you.” The first part was easy, take each letter in your name and convert it to a number. Use the system where an A=1, B=2, .. -

11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. Review Words Challenge Words

Spelling: Digraphs Name Fold back the paper 1. 1. thirty along the dotted line. 2. 2. width Use the blanks to write each word as it is read 3. 3. northern aloud. When you fi nish 4. 4. fi fth the test, unfold the paper. Use the list at 5. 5. choose the right to correct any 6. 6. touch spelling mistakes. 7. 7. chef 8. 8. chance 9. 9. pitcher 10. 10. kitchen 11. 11. sketched 12. 12. ketchup 13. 13. snatch 14. 14. stretching 15. 15. rush 16. 16. whine 17. 17. whirl 18. 18. bring 19. 19. graph 20. 20. photo Review Words 21. 21. unload Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 22. 22. relearn 23. 23. subway Challenge Words 24. 24. expression 25. 25. theater Phonics/Spelling • Grade 4 • Unit 2 • Week 2 37 Spelling: Digraphs Name thirty choose pitcher snatch whirl width touch kitchen stretching bring northern chef sketched rush graph fi fth chance ketchup whine photo A. Underline the spelling word in each row that rhymes with the word in bold type. Write the spelling word on the line. 1. much match touch luck 2. sting bring brag stint 3. fetching resting guessing stretching 4. pants stand lamp chance 5. dirty thirty forty wiry 6. shine mind whine lane 7. news loose stew choose 8. catch clutch snatch snake 9. laugh graph rough roof 10. fl ush crash rush puts Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. 11. clef chef step leaf 12. etched skipped punched sketched 13. hurl hurt whirl while 14. richer pitcher sister listener B. -

Sixth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in Accordance with Article 15 of the Charter

Strasbourg, 1 July 2014 MIN-LANG (2014) PR7 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Sixth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter NORWAY THE EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES SIXTH PERIODICAL REPORT NORWAY Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation 2014 1 Contents Part I ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ................................................................................................................................ 3 Users of regional or minority languages ................................................................................ 5 Policy, legislation and practice – changes .............................................................................. 6 Recommendations of the Committee of Ministers – measures for following up the recommendations ................................................................................................................... 9 Part II ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Part II of the Charter – Overview of measures taken to apply Article 7 of the Charter to the regional or minority languages recognised by the State ...................................................... 14 Article 7 –Information on each language and measures to implement