The James Blair Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

124900176.Pdf

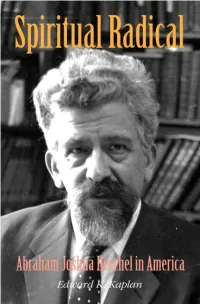

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

January 2013 Vol

Members get an additional 5% off their purchases all week! Details on back Call for Candidates page. DAY Weavers Way Co-op needs members to run for a seat on the Board of Directors. Send inquiries to: [email protected] Details on back page. JANUARY 13 - 19 The Shuttle January 2013 Vol. 41 No. 12 A Cooperative Grocer Serving the Northwest Community Since 1973 Wanted: A Book Drive Delivers Smiles Amendment Few Good Threatens Cooperators for Urban Farms in the Board Philly by Margaret Lenzi, Weavers Way by Jon McGoran, Shuttle Editor Board President ON DECEMBER 13, 2012, less than four DO YOU have an interest in serving Weav- months after the widely anticipated imple- ers Way and a commitment to its mission, mentation of the city’s brand new zoning values, and goals? Are you a conceptual code, City Council’s Committee on Rules thinker who can grasp the big picture? Can has voted to approve an ordinance that you work in a group to oversee a vibrant undoes important aspects of the code, in- developing organization? cluding the gains made for urban agricul- ture in Philadelphia. Introduced by Coun- If this sounds like you so far, you might photo courtesy of Harrity Elementary School be interested in running for the Weavers cilman Brian O’Neill, Bill 120917 creates Third graders at Harrity Elemenary with books collected at Weavers Way, Big Blue Marble restrictions on a range of uses in commer- Way Board. And you thought the election Bookstore, and Valley Green Bank, through the bank’s annual Book Drive. -

Jewish Organizational Life in the United States Since 1945

Jewish Organizational Life in the United States Since 1945 by JACK WERTHEIMER .T\FTER MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY of expansive institutional growth at home and self-confident advocacy on behalf of coreligionists abroad, the organized Jewish community of the United States has entered a period of introspection and retrenchment in the 1990s. Voices emanating from all sectors of the organized community demand a reallocation of funds and energy from foreign to local Jewish needs, as well as a rethinking of priorities within the domestic agenda. Their message is unambiguous — "The future begins at home."1 Institutional planners are also advocating a "radical redesign" of the community's structure: some insist that agencies founded early in the 20th century are obsolete and should merge or disap- pear; others seek to create entirely new institutions; others castigate com- munal leaders as "undemocratic" or irrelevant to the lives of most Jews and demand that they step aside; and still others urge a "major overhaul" of the community's priorities as a way to win back the alienated and disaffiliated.2 In short, the organized Jewish community is engaged in a far-reaching reassessment of its mission and governing institutions. Note: The author acknowledges with appreciation generous support from the Abbell Fac- ulty Research Fund at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Much of the research for this essay was conducted at the Blaustein Library of the American Jewish Committee, whose staff graciously provided much helpful assistance.The author also thanks Jerome Chanes and Peter Medding for reviewing the manuscript. 'See, for example, Larry Yudelson, "The Future Begins at Home," Long Island Jewish World, Mar. -

HISTORICAL PAPERS 2008 Canadian Society of Church History

HISTORICAL PAPERS 2008 Canadian Society of Church History Annual Conference University of British Columbia 1-3 June 2008 Edited by Brian obbett, Bruce L. uenther and Robynne Rogers Healey 'Copyright 2008 by the authors and the Canadian Society of Church History Printed in Canada ALL RI H,S RESER-E. Canadian Cataloguing in Pu lication Data Main entry under title0 Historical Papers June 213 213884- Annual. A selection of papers delivered at the Society5s annual meeting. Place of publication varies. Continues0 Proceedings of the Canadian Society of Church History, ISSN 0872-1089. ISSN 0878-1893 ISBN 0-3939777-0-9 213334 1. Church History;Congresses. 2. Canada;Church history;Congresses. l. Canadian Society of Church history. BR870.C322 fol. 277.1 C30-030313-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Papers Air Wars0 Radio Regulation, Sectarianism, and Religious Broadcasting in Canada, 1322-1338 MARK . MC OWAN 8 A Puppy-.og ,ale0 ,he United Church of Canada and the Youth Counter-Culture, 1398-1373 BRUCE .OU-ILLE 27 @Righteousness EAalteth a NationB0 Providence, Empire, and the Corging of the Early Canadian Presbyterian Identity .ENNIS MCKIM 77 Crom the UDraine to the Caucasus to the Canadian Prairies0 Life as Wandering in the Spiritual Autobiography of CeoDtist .unaenDo SER EY PE,RO- 97 Eelma and Beulah Argue0 Sisters in the Canadian Pentecostal Movement, 1320-1330 LIN.A M. AMBROSE 81 Canadian Pentecostalism0 A Multicultural Perspective MICHAEL WILKINSON 103 ,homas Merton, Prophet of the New Monasticism PAUL R. .EKAR 121 Balthasar Hubmaier and the Authority of the Church Cathers AN.REW P. KLA ER 133 CSCH President&s Address @Crom the Edge of OblivionB0 Reflections on Evangelical Protestant .enominational Historiography in Canada BRUCE L. -

Bk Gandhi Peace Awards

In Gandhi’s Footsteps: The Gandhi Peace Awards 1960-1996 by James Van Pelt for PROMOTING ENDURING PEACE 112 BEACH AVENUE • WOODMONT CT 06460 2 IN GANDHI’S FOOTSTEPS: THE GANDHI PEACE AWARDS Promoting Enduring Peace Gandhi Peace Award Recipients 1960-1996 Introduction Chapter Year Award Recipient Page 1 1960 Eleanor Roosevelt 1960 Edwin T. Dahlberg 2 1961 Maurice N. Eisendrath 1961 John Haynes Holmes 3 1962 Linus C. Pauling 1962 James Paul Warburg 4 1963 E. Stanley Jones 5 1965-66 A.J. Muste 6 1967 Norman Thomas 7 1967 William Sloane Coffin, Jr. 1967 Jerome Davis 8 1968 Benjamin Spock 9 1970 Wayne Morse 1970 Willard Uphaus 10 1971-72 U Thant 11 1973 Daniel Berrigan RE- SIGNED 12 1974-75 Dorothy Day 13 1975-76 Daniel Ellsberg 14 1977-78 Peter Benenson Martin Ennals 15 1979 Roland Bainton 16 1980 Helen Caldicott 17 1981 Corliss Lamont 18 1982 Randall Forsberg 19 1983-84 Robert Jay Lifton 20 1984 Kay Camp 21 1985-86 Bernard Lown 22 1986-87 John Somerville 23 1988-89 César Chávez 24 1989-90 Marian Wright Edelman 25 1991 George S. McGovern 26 1992 Ramsey Clark 27 1993 Lucius Walker, Jr. 28 1994 Roy Bourgeois 29 1995 Edith Ballantyne 30 1996 New Haven/León Sister City Project 31 1997 Howard & Alice Frazier Conclusion Note: A listing of dual years (e.g. 1988-89) indicates that the decision to present the Award to the recipient was made in one year, with the Award actually being presented the following year. 4 IN GANDHI’S FOOTSTEPS: THE GANDHI PEACE AWARDS Introduction he Gandhi Peace Award: it is a certificate, calligraphed with an inscription T summing up the work for peace of a distinguished citizen of the world. -

Marvin S. Antelman to Eliminate the Opiate Vol 1

TO ELIMINATE — OPIATE aaah Read about... Jacob Frank, to whom sin was holy. Adam Weishaupt. the Jesuit priest who founded the Iluminati on May Day 1776, from which the Communist Party emerged. How Weishaupt's Iluminati and Frank's Frankists worked hand in hand to destroy religions and governments. The connection between the Frankists. Illuminati, Jacobins and the French Revolution that changed society. Why Jewish-born Karl Marx was an anti-Semite and wrote A World Without Jews. The 18th Century roots of the Women's Liberation movement. How the Illuminati founded artificial Judaism. Why the Frankists provided the leadership for the Reform and Conservative movements. How Judaism was labeled iOrthodoxi in order to destroy it. How the Lubaviteher Rebbe foiled a mass assimilation conspiracy in Russia. The plot to destroy the Torah through the field of Biblical criticism. Why today’s Reform clerics gravitate to Communism, Communist causes, and support Black anti-Semitic groups Why the wealthy financed Communist revolutions. Why Black civic leader Elma Lewis sued the author for a half million dollars and Lost. The true sources for the Frankenstein Monster. The significance of mystical designs on the American dollar bill. TO ELIMINATE THE OPIATE VOLUME | By Rabbi Marvin S. Antelman IN MEMORIAM This book is dedicated to the memory of members of my family who perished in the Holocaust of the National Socialist Party of Germany, during World War Il. They met their death in the environs of Sokoran, in the province of Bessarabia, Rumania. Their names are as follows: My grandfather, Alexander Ze'ev Zisi Antelman My grandmother, Golda Antelman My uncle, Baruch Antelman My aunt, Sima Antelman Their 8-year-old daughter, my cousin, Rivka Antelman My aunt, Rivka (Antelman) Groberman My uncle, Mayer Groberman Their 13-year-old son, my cousin, Moshe Groberman Their 17-year-old daughter, my cousin, Rachel Groberman My 2-year-old cousin, Hadassah Antelman And a total of 60 of my cousins' uncles, aunts, cousins and grandparents. -

July-September 2014, Volume 41(PDF)

REFLECTIONS All Who Are Born Must Die by Nichiko Niwano February 15 is the date on which Rissho before that, sorrow at being confronted Nichiko Niwano is president of Kosei-kai holds the ceremony marking with the ruin of his country—accept- Rissho Kosei-kai and an honorary the day when, some twenty-five hun- ing such dire circumstances. Therefore, president of Religions for Peace. dred years ago, Shakyamuni entered nir- when I was reciting chapter 16 of the He also serves as special advisor vana. This observance of Shakyamuni’s Lotus Sutra, “The Eternal Life of the to Shinshuren (Federation of New entrance to nirvana is, along with the Tathagata,” and read, “The words of the Religious Organizations of Japan). anniversaries of the day of Shakyamuni’s Buddha are true, not false,” I was struck birth and the day of his enlightenment, by the thought that what the Buddha told one of the three important annual events us is the truth, not meaningless words. was eased by this. I whiled away today for Buddhists, and while we praise his I then pondered anew the importance doing nothing.” Conversely, when we virtues on this day, we also take the of accepting the truth of life and death lead our lives supposing that tomor- opportunity to again reflect upon what as the highest priority in our existence. row may never come, we fully expe- matters most in life. rience each and every moment of life. In this regard, as Zen master Dogen Shining Light into When we can accept the fact of death (1200–1253) declared, “The most impor- Hearts and Minds in this way, we need not uselessly fear tant matter for a Buddhist is to be com- it or find the thought of it abhorrent. -

Social Justice in the Jewish Tradition Adapted from the Union for Reform Judaism’S “Torah at the Center” Volume 3, No.1 60 Minutes

The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism: Celebrating 50 Years in Pursuit of Social Justice! Social Justice in the Jewish Tradition Adapted from the Union for Reform Judaism’s “Torah at the Center” Volume 3, No.1 60 minutes Audience: 4th-12th grade Goals: • Explore the Jewish concept of “Tzedek” • Contemplate the connection between justice and the Civil Rights Movement • Educate about the Jewish community’s role in the Civil Rights Movement • Inspire further engagement with issues of social justice Timeline: 0:00-0:15 Introduction to the Jewish Concept of Justice 0:15-0:40 Justice Exploration Activities 0:40-0:50 Jews and the Civil Rights Movement 0:50-1:00 Current Issues of Justice Materials: • Pens, paper • White board or butcher paper • A computer that can play music • One copy of the Tanakh—Hebrew, with English translation— per 5 students (intermediate grades) Background The Jewish commitment to social justice in general and to the struggle for civil rights in particular is not a modern phenomenon. To understand our historic and continued passion for the work of justice, it is critical to comprehend the concept of justice, or tzedek, in Jewish tradition. Tzedek, Tzedek Tirdof; Justice, justice shall you pursue. The Jewish concept of justice stresses equality, the idea that every human life has equal value. In Jewish life the attainment of justice is critical to the attainment of holiness. This idea was the basis for the significant Jewish involvement in the struggle for black civil rights in America. In Judaism, however, justice is not simple. It is a large concept, encompassing a variety of ethics and ideals. -

THE SCRIBE the JOURNAL of the JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY of BRITISH COLUMBIA the Scribe the Scribe • Vol

Volume XXX • 2010 JEWISH COMMUNITY • FOCUS ON THE COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER • BOOKS IN REVIEW REVIEW IN BOOKS • COMMUNITY THE NEWSPAPER COMMUNITY JEWISH FOCUS• ON THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA The Scribe The • Vol. XXX • 2010 • XXX Vol. • Featured in this issue THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Jewish Community • Focus on the Community Newspa- per • Books in Review THE SCRIBE THE JOURNAL OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Jewish Community Focus on the Community Newspaper Books in Review Volume XXX • 2010 This issue of The Scribe has been made possible through a generous donation from Dora and Sid Golden and Family. Editor: Cynthia Ramsay Publications Committee: Faith Jones, Betty Nitkin, Cheryl Rimer, Perry Seidelman and Jennifer Yuhasz, with appreciation to graphic designer Josie Tonio McCarthy and proofreaders Marcy Babins and Basya Laye Layout: Western Sky Communications Ltd. Statements of fact or opinion appearing in The Scribe are made on the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply the endorsements of the editor or the Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia. Please address all submissions and communications on editorial and circulation matters to: THE SCRIBE Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia 6184 Ash Street, Vancouver, B.C., V5Z 3G9 604-257-5199 • [email protected] • www.jewishmuseum.ca Membership Rates: Households – $54; Institutions/Organizations – $75 Includes one copy of ea ch issue of The Scribe and The Chronicle Back issues and extra copies – $20 including postage ISSN 0824 6048 © The Jewish Historical Society of British Columbia is a nonprofit organization. -

SANE and the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963: Mobilizing Public Opinion to Shape

SANE and the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963: Mobilizing Public Opinion to Shape U.S. Foreign Policy A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Erin L. Richardson November 2009 © 2009 Erin L. Richardson. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled SANE and the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963: Mobilizing Public Opinion to Shape U.S. Foreign Policy by ERIN L. RICHARDSON has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Chester J. Pach Jr. Associate Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT RICHARDSON, ERIN L., M.A., November 2009, History SANE and the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963: Mobilizing Public Opinion to Shape U.S. Foreign Policy (115 pp.) Director of Thesis: Chester J. Pach Jr. This thesis examines the role of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) in building support for the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963. Focusing on SANE’s highly publicized newspaper advertisements shows how the organization succeeded in using the growing public fear of the potentially lethal effects of radioactive fallout from atmospheric testing to raise awareness of the nuclear test ban. SANE ads successfully sparked national interest, which contributed to a renewal of U.S. efforts to negotiate a treaty. It also strengthened SANE’s credibility and expanded the role of the organization’s co-chair and Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins in working with the Kennedy Administration. -

Philip S. Bernstein Papers

Philip S. Bernstein papers This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 26, 2021. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, River Campus Libraries, University of Rochester Rush Rhees Library Second Floor, Room 225 Rochester, NY 14627-0055 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.rochester.edu/spaces/rbscp Philip S. Bernstein papers Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical/Historical note .......................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents note ............................................................................................................................. 13 Arrangement note ......................................................................................................................................... 18 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................... 19 Controlled Access Headings ........................................................................................................................ 19 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 20 Temple B'rith Kodesh .............................................................................................................................. -

V3 2017 the Next Faith System

The Next Faith System By Steve Brown (Cover Photo Credit: Alice Robertson Brown) © 2017 Steve Brown [email protected] 508-560-1189 I. Introduction “…if there is a God what the hell is He for?” [William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying]1 Early in his 1930 novel As I Lay Dying, William Faulkner’s character Jewel poses this question, a timely one to ask in rural Mississippi in 1930, and even more so today. Faulkner applied it to issues as diverse as abortion, infidelity, access to health care, and the stink of an eight-day dead body—both literally and metaphorically. Faulkner’s question begs to be asked again and again as each day we witness worsening chaos in many world systems, including the faith system in America. I believe this question addresses much more than religious or spiritual issues. What does the word “God” imply for people in America and the world in 2017? Who decides? And what actions does this decision mandate? Certainly the meaning of this word “God” has evolved in America’s consciousness in the last fifty years as the nation has become more diverse, and this evolution has brought diverse identities and purposes. Yet, if the nation is to endure as one indivisible entity, it must somehow encompass all these identities and purposes. With this in mind, I have set aside the word “God” and chosen the term “faith system” as a context for exploring Faulkner’s question. I do not believe that America’s current faith system is up to the task of envisioning and creating a sustainable future.