HISTORICAL PAPERS 2008 Canadian Society of Church History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Story and Vision: Exploring the Use of Stories for Growth in the Life of Faith.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 8, No

Valenzuela, Michael. “Story and Vision: Exploring the Use of Stories for Growth in the Life of Faith.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 8, no. 2 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2017). © Michael Valenzuela, FSC, PhD. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. Story and Vision: Exploring the Use of Stories for Growth in the Life of Faith Michael Valenzuela, FSC2 Chapter One Statement of the Problem The use of story in communicating religious understanding and tradition is as old as religion itself. Human beings have always resorted to the language of story (image, symbol, metaphor, narrative) to speak of their encounters with Mystery. Telling stories is so much a part of what we do as human beings that we often take it for granted. Thus, the turn to story in religious education is nothing new, rather, it stems from a growing recognition and appreciation of the centrality of narratives to growth in personal and communal faith. How can different forms of stories be used to facilitate the growth in the life of faith among Catholic elementary and high school students in the Philippines? This is the question this extended essay seeks to address. Scope and Limitations “Story” is one of those deceptively simple words that everyone seems to use and hardly anyone can adequately define. A helpful definition offered by the Christian ethicist Stanley Hauerwas describes story as “a narrative account that binds events and agents together in an intelligible pattern.”3 While strictly speaking, one can differentiate between story and narrative, for the purposes of this extended essay, I will treat these two terms as meaning essentially the same thing. -

Appropriating the Principles of L'arche for the Transformation of Church Curricula Nathan Goldbloom Seattle Pacific Seminary

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Theses and Dissertations January 1st, 2014 Appropriating the Principles of L'Arche for the Transformation of Church Curricula Nathan Goldbloom Seattle Pacific Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/etd Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Goldbloom, Nathan, "Appropriating the Principles of L'Arche for the Transformation of Church Curricula" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 10. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/etd/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. APPROPRIATING THE PRINCIPLES OF L’ARCHE Appropriating the Principles of L’Arche for the Transformation of Church Curricula Nathan Goldbloom Seattle Pacific Seminary July 13, 2014 APPROPRIATING THE PRINCIPLES OF L'ARCHE I 2 Appropriating the Principles of L'Arche for the Transformation of Church Curricula By Nathan Goldbloom A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Christian Studies Seattle Pacific Seminary at Seattle Pacific University Seattle, WA 98119 2014 Approved by: ----u---~--=-----......::.......-=-+-~-·-~------'---- Richard B. Steele, PhD, Thesis Advisor, Seattle Pacific Seminary at Seattle Pacific University Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Seattle Pacific Seminary at Seattle Pacific University Authorized by: ~L 151.<qft,~ Douglas M. Strong, PhD, Dean School of Theology, Seattle Pacific University Date: /lw.J "J J 1 Jo I 't APPROPRIATING THE PRINCIPLES OF L’ARCHE | 3 Introduction L’Arche Internationale is a network of communities in which per- sons with cognitive disabilities live and work with non-disabled ‘assis- tants’. -

How a United Church Congregation Articulates Its Choices from the 41St General Council's

“What Language Shall I Borrow?” How a United Church Congregation Articulates its Choices from the 41st General Council’s Recommendations Regarding Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine by Donna Patricia Kerrigan A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emmanuel College and the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry awarded by Emmanuel College and the University of Toronto © Copyright by Donna Patricia Kerrigan 2016 “What Language Shall I Borrow?” How a United Church Congregation Articulates its Choices from the 41st General Council’s Recommendations Regarding Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine Donna Patricia Kerrigan Doctor of Ministry Emmanuel College and the University of Toronto 2016 Abstract The thesis of this dissertation is that members of the United Church of Canada who respond to the Report on Israel/Palestine Policy select from its peacebuilding recommendations according to their attitudes to theological contextualizing. Two attitudes give rise to two different methods, which are seldom articulated but underlie choices regarding peace initiatives such as boycotting or ecumenical/multifaith cooperation. The dissertation includes five parts: an investigation of contextual theologies for peacebuilders; a history of the UCC and ecumenical partners who have struggled to assist peace in Israel/Palestine; strategies for peace-minded ministers; a case-study of one congregation choosing peace strategies; and recommendations for denominational communications and peacebuilding. This thesis poses a taxonomy for theologizing in context, moving from initial interaction with the other by translating local systems of thought into terms of the Gospel message. Contextualizers proceed either to immerse in the local culture (anthropological) or to engage with locals in mutual learning (synthesis). -

Jean Vanier Was a Canadian Humanitarian and Social Visionary

Jean Vanier was a Canadian humanitarian and social visionary. Founder of L’Arche and co-founder of Faith and Light, Vanier was a passionate advocate for persons with intellectual disabilities and a world where each person BACKGROUND is valued and belongs. EAN VANIER was born on September 10, 1928, in Geneva, JSwitzerland, the fourth of five children of Canadian parents, future Governor General Georges Vanier and Madame Pauline Vanier. Jean received a broad education in England, France, and Canada. At age 13, he informed his parents of his intention to leave Canada to join the Royal Navy in Great Britain. His father responded, “I don’t think it’s a good idea, but I trust you.” Jean said that his father’s trust in him touched him deeply and gave him confidence in his inner voice throughout his life. Vanier entered the Royal Navy at Dartmouth Naval College in 1942. From 1945 to 1950, he served on several warships, accompanying the British royal family in 1947 on their tour of South Africa aboard the HMS Vanguard. He transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy in 1949. During this period he began to pray during long stretches serving watch on the ship’s bridge and came to realize that his future would move beyond the life of a naval officer. He resigned his naval commission in 1950 and devoted “Jean Vanier’s inspirational himself to theological and philosophical studies, obtaining his work is for all humanity, doctorate in 1962 from the Institut Catholique in Paris with a including people with widely praised dissertation, “Happiness as Principle and End of intellectual disabilities. -

A Short History of the United Church of Canada's Young Peoples Union

A Short History of the United Church of Canada’s Young Peoples Union (YPU) Introduction The purpose of this short history is to ensure that the story of the Young Peoples Union movement in the United Church of Canada is remembered and preserved in the files of the Archives of the United Church of Canada. Although this short history is based on the files, stories and achievements of one church; namely, Parkdale United Church of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, the same can be said of many United Churches across Canada during the period after Church Union in 1925. The period from approximately 1930 to 1964 saw the development of the United Church Young Peoples Unions (YPU); some were called “Societies”, (YPS) until 1935. They began to form in churches after the June 10, 1925 union of some of the Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational churches to form the United Church of Canada. It was organized at the National, Conference and Presbytery levels. The YPU had considerable autonomy given to it from the Board of Christian Education. The YPU was born in the Depression years of Canada, 1929-1938, went through the Second World War period, 1939-1945, grew during the post-war period, endured the Korean War of 1950-1953, thrived in the late 50’s as the population of Canada grew, and started to dwindle in the mid-1960s. To examine the Young Peoples Union movement is to look at a very interesting stage of church development and to see 1 how one part of the United Church helped its young people to learn, grow and develop leadership skills and Christian values that have continued to this day. -

Open New Homes in Greater Washington

homematteSummerr 2013s building communities of faith and lifelong homes with people who have intellectual disabilities join our community Looking for an adventure in community living that will help you There is no fear in love. discover the depths of the human But perfect love drives spirit? L’Arche accepts applications out fear. —1 John 4:18 on a rolling basis for assistants for the Washington, D.C., and Arlington, Virginia, homes. Find out more and watch our video about being an Finding Calm assistant at www.larche-gwdc.org. in Love contact us L’Arche Office by james schreiner Mari Andrew Housemates James Schreiner and Hazel Pulliam explore Lourdes, France, 202.232.4539 together. Photo by Michele Bowe [email protected] On Tuesday mornings, members of L’Arche in Arlington meet in the role of assistant, but other fears persisted. As our Recruitment for what we call “faith and sharing”—an occasion to de- Arlington households continued to meet for Tuesday faith Caitlin Smith scribe how we are growing in our community and the joys and sharing, I confided additional struggles with worry and 202.580.5638 and challenges of previous weeks. As we share in a spirit of self-acceptance and often felt a miraculous sense of peace [email protected] trust, we experience vulnerability together. soon after our meetings. Community Life When our community first welcomed me in July 2011, I faced In addition to challenges, I also had joyful moments in Bob Jacobs (D.C. homes) much fear. Transitions have always been difficult for me, and community life. -

Maritime Conference the United Church of Canada the 89 Annual

Maritime Conference The United Church of Canada The 89th Annual Meeting Sackville, New Brunswick May 22 - 25, 2014 SECTION 1 REPORTS TO CONFERENCE President’s Message This past year has gone by faster than I’d ever anticipated. I have already visited three Presbyteries, and been guest-preacher at two pastoral charges; I am scheduled to visit three more presbyteries, and Bermuda Synod, over the next two months. I have had the privilege of representing Maritime Conference on a number of pastoral occasions. And each visit I have done, has impressed me with the dedication of the church folk who are there. There is confusion and sadness, certainly, as many see attendance falling away from regular Sunday worship services, and as our congregations age. But there is also a sense of excitement, as pastoral charges and congregations start to explore new ways of being church in their communities and in their world. Home church, mission church, coffee bar church, shared ministry, cyber congregations —all are part of the options opening up to those who are passionate about being the hands and feet of Christ. As I sit at my desk this (very!) cold February afternoon, I am reminded of the words of the hymn that tells us, “In the cold and snow of winter, there’s a spring that waits to be, unrevealed until its season, something God alone can see!” Our church is in that waiting stage. We are waiting to see what sort of spring is coming for our church, our mission, our identities as people of faith and a community of Christ. -

Scripture's Role in Discerning Theology in the United Church of Canada

Scripture’s Role in Discerning Theology in The United Church of Canada by John William David McMaster A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Knox College and the Toronto School of Theology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry awarded by Knox College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by John William David McMaster 2016 Scripture’s Role in Discerning Theology in The United Church of Canada John William David McMaster Doctor of Ministry Knox College and the University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Traditionally, the Bible has been at the centre of the Church’s life and thought. It has been viewed as the Word of God, a unique work, revealing God and God’s ways to humankind. Authority and the authority of scripture have been questioned, however, in recent years particularly within mainline Protestant denominations. The following study seeks to clarify the role of scripture in discerning theology within congregational life of the United Church of Canada. It begins by examining the view of scripture held by the Protestant Reformers of the 16th and 18th centuries. It moves to discuss how those views have been affected by the rise of modernist and postmodernist thought, and then looks at the changing role of scripture within the history of the United Church. These contextual studies form the base for a case study of the practices and thought of three United Church Councils in the city of Toronto. There, it was found that more experiential factors were the chief influences on United Church lay leaders today as they make theological ii decisions. -

Report of the Joint Partnership Committee Page 1 the United

A Journey to Full Communion The Report of the Joint Partnership Committee The United Church of Christ and The United Church of Canada April 2015 The United Church of Canada and The United Church of Christ (USA) share a rich and similar history as “united and uniting” churches in North America. In 2013, both denominations authorized a Joint Partnership Committee to discern the call of God towards entering full communion. After a year of discernment, the committee is recommending through each denomination’s respective executive body that the 30th General Synod of The United Church of Christ, which will meet June 26-30, 2015, in Cleveland, Ohio, and the 42nd General Council of The United Church of Canada, which will meet August 8-15, 2015, in Corner Brook, Newfoundland and Labrador, approve a full communion agreement. This document is the formal report of the committee, and is meant to accompany the proposal and serve as a resource for those who will carry the commitment to a full communion relationship into the future. United and Uniting The United Church of Canada came into being in 1925 as the first union in the 20th century to cross historic denominational lines. While union discussions in Canada first began at the end of the 19th century, the Methodist Church in Canada, the Presbyterian Church in Canada (about one-third of Presbyterian churches in Canada stayed out of union), and the Congregational Union of Canada, along with a large number of Local Union Churches which had formed in anticipation of union, formally celebrated the formation of the new church on June 10, 1925 in Toronto, Ontario. -

Tenure and Academic Freedom in Canada

Vol. 15: 23–37, 2015 ETHICS IN SCIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS Published online October 1 doi: 10.3354/esep00163 Ethics Sci Environ Polit Contribution to the Theme Section ‘Academic freedom and tenure’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Tenure and academic freedom in Canada Michiel Horn* York University, Toronto, ON, Canada ABSTRACT: In Canada, a persistent myth of academic life is that tenure was initiated and devel- oped in order to protect academic freedom. However, an examination of the historical record shows that in both its forms — viz. tenure during pleasure, whereby professors could be stripped of their employment if it suited a president and governing board, and tenure during good behav- ior, whereby professors were secure in their employment unless gross incompetence, neglect of duty, or moral turpitude could be proven against them — the institution took shape as the main defense of academic employment. In this paper, I explore the development of tenure since the middle of the 19th century, and the concepts of academic freedom with which tenure has become closely associated. I also make the case that tenure during good behavior has become a major sup- port of the academic freedom of professors even as that freedom is undergoing new challenges. KEY WORDS: University of Toronto · Sir Robert Falconer · McGill University · University of British Columbia · University of Manitoba · University of Alberta · Harry S. Crowe · Canadian Association of University Teachers INTRODUCTION academic freedom as it is understood today, the free- dom to teach, research, and publish, the freedom to Is the defense of academic freedom central to the express oneself on subjects of current interest and im- institution of tenure? Most Canadian academics are portance, and the freedom to criticize the institution in likely to answer, reflexively, in the affirmative. -

124900176.Pdf

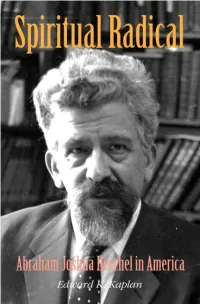

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Finding Aid 499 Fonds 499 United Church of Canada

FINDING AID 499 FONDS 499 UNITED CHURCH OF CANADA OFFICE OF THE MODERATOR AND GENERAL SECRETARY FONDS UNITED CHURCH OF CANADA Accession Number 1982.002C Accession Number 2004.060C Accession Number 2017.091C Accession Number 1983.069C Accession Number 2004.104C Accession Number 2017.111C Accession Number 1988.123C Accession Number 2004.104C Accession Number 2017.149C Accession Number 1989.161C Accession Number 2005.129C Accession Number 2018.047C Accession Number 1991.163C Accession Number 2006.001C/TR Accession Number 2018.060C/TR Accession Number 1991.196C Accession Number 2007.002C Accession Number 2018.062C Accession Number 1992.074C Accession Number 2007.017C Accession Number 2018.070C Accession Number 1992.082C Accession Number 2007.024C Accession Number 2018.083C Accession Number 1992.085C Accession Number 2007.034C Accession Number 2018.085C Accession Number 1993.076C Accession Number 2008.059C Accession Number 2018.104C/TR Accession Number 1993.144C Accession Number 2009.007C Accession Number 2018.114C Accession Number 1994.045C Accession Number 2009.008C Accession Number 2018.120C Accession Number 1994.162C Accession Number 2009.101C Accession Number 2018.128C Accession Number 1994.172C/TR Accession Number 2009.110C/TR Accession Number 2018.134C/TR Accession Number 1996.026C Accession Number 2010.034C/TR Accession Number 2018.157C Accession Number 1998.167C/TR Accession Number 2012.139C Accession Number 2018.199C Accession Number 2000.100C Accession Number 2014.003C/TR Accession Number 2018.249C/TR Accession Number 2000.117C