Transatlantic Charter Policy - a Study in Airline Regulation Jack M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

LCD-76-214 Review of the Military Airlift Command's Use of Chartered

UNITED STATES GENERALAcC~UNTM OFFICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20548 LOGISTICS AND COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION B-133025 ’ P’ Th.e Honor able The Secretary of Defense Dear Mr. Secretary: As a follow-on to our review of fuel savings and other benefits by diverting passengers from chartered to scheduled overseas flights, we reviewed the Military Airlift Command’s L’1;,(MAC’s) use of c.hartered cargo aircraft. In examining an 8-month period l/ we found 42 instances in which it appeared MAC could, have used the carrier’s regularly scheduled com- mercial service instead of chartered aircraft. We estimate the Department of Defense (DOD) could have saved as much as $425,000 by shipping this cargo on scheduled flights. In addition, the airlines would have saved about $172,000 in operating costs, including about one million gallons of jet fuel. BACKGROUND MAC contracts with commercial air carriers as needed for supplemental airlift of cargo from MAC’s domestic aerial ports to overseas military terminals. Rates for this serv- ice are established by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). I”- 3 MAC contracts move cargo in planeload lots on a charter ba- sis and, in some instances, in less .than planeload lots in blocked space on scheduled flights. Cargo moving on scheduled flights is palletized at the MAC aerial port by Air Force personnel and then turned over to the contract carrier. The contract carrier is respon- sible for draying the cargo to the commercial air terminal at origin and for delivering the cargo from the commercial terminal to the appropriate military terminal in the over- seas area. -

Federal Aviation Agency

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 30 • NUMBER 57 Thursday, March 25, 196S • Washington, D.C. Pages 3851-3921 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Comptroller of the Currency Consumer and Marketing Service Economic Opportunity Office Engineers Corps Federal Aviation Agency Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Immigration and Naturalization Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau National Shipping Authority Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Veterans Administration Wage and Hour Division Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Subscriptions Now Being Accepted S L I P L A W S 89th Congress, 1st Session 1965 Separate prints of Public Laws, published immediately after enactment, with marginal annotations and legislative history references. Subscription Price: / $12.00 per Session Published by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 20402 i & S A Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on^ on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Regi . ^ ay0Iiai FEDERAL®REGISTER LI address Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail adore ^ th0 Area Code 202 Phone 963-3261 fcy containe< -vwiTEo-WilTED’ nrcmvesArchives jsuuamg,Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to tnethe authority coni Admin- Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935' (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C., ch. 8B b under regulations prescribedIbed by thetne ent istrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (1 CFR Ch. -

Mr. Elgen M. Long 8 May 2001 Brian Shoemaker Interviewer (Begin

Mr. Elgen M. Long 8 May 2001 Brian Shoemaker Interviewer (Begin Tape 1 - Side A) (000) BS: This is an oral interview with Mr. Elgen Long, taken as part of the Polar Oral History Project, conducted by the American Polar Society and the Byrd Archival Program of The Ohio State University on a grant provided by the National Science Foundation. The interview was conducted by Brian Shoemaker in Mr. Shoemaker's home on the 8th of May, 2001. Mr. Long . Elgen. EL: Brian. BS: You have a very distinguished flying career with the Flying Tiger Airlines and privately as well. We're interested in your polar flying in the Arctic and the Antarctic, but you just didn't materialize in the polar regions. You were an experienced pilot before you went. And backing up further, something prompted you to fly and before that someone or some event inspired you to get going and you wound up with a whole repertoire of things that you were capable of and made you successful as a polar flyer. So, take it back as far 2 as you like and feel free to fill in between your polar flying experiences and your experiences, certainly, on studying Amelia Earhart. EL: Well, thank you, Brian, for inferring that I had a brilliant career with the Flying Tiger Line. It was no more brilliant than your flying career with the United States Navy. But, I started with the Navy, too, actually, and as you suggested, life is a number of choices along the way and opportunities that present themselves that you either take advantage of or don't. -

March/April – 2006 1 PERPETUAL CALENDAR 2006 JULY 5-9 International Ninety-Nines Conference, APRIL Washington, D.C., Marriott Hotel

99 News – March/April – 2006 1 PERPETUAL CALENDAR 2006 JULY 5-9 International Ninety-Nines Conference, APRIL Washington, D.C., Marriott Hotel. 99 News 1 Deadline for the May/June issue of 6-23 National Cross Country Air Races. Handi- 99 News. capped speed racing open to all pilots and all piston aircraft. July 16-18, Hutchinson To list your 99s events 4-10 Sun ’n Fun, Lakeland, Florida. Stop by The 300, Hutchinson, Kansas; July 19-21, 1800 on this calendar page, Ninety-Nines building and visit with Mile Marion Jayne Air Race, Hutchinson, send information to: WASP. Contact www.sun-n-fun.org. KS-HUT, Akron, CO-AKO, Rapid City, SD- The 99 News 23-24 New York/New Jersey Spring Section RAP, Wolf Point, MT-OLF, Devils Lake, ND- DVL, Orr, MN-ORR, Stevens Point, WI-STE; 4300 Amelia Earhart Rd. Meeting, Newark, NJ. Hosted by the West- ern New York Chapter. July 21-23, Wisconsin 300, Stevens Point, Oklahoma City, OK Wisconsin. Free entry kit on line at 73159-1140 28-29 North Central Spring Section Meeting, www.us-airrace.org. Kansas City, MO. Email: 19-21 Marion Jayne Air Race, Hutchinson, KS- [email protected] 28-30 Southeast Spring Section Meeting, HUT, Akron, CO-AKO, Rapid City, SD-RAP, Online Form: Fayetteville, NC. Contact Stephanie Hahn, Wolf Point, MT-OLF, Devils Lake, ND-DVL, www.ninety-nines.org/ 913-980-1590. Orr, MN-ORR, Stevens Point, WI-STE. In- 99newsreports.html 28-30 Mid-Atlantic Section Meeting, Holiday formation: [email protected]. Please indicate the Inn, Greenfield Road, Lancaster, PA. -

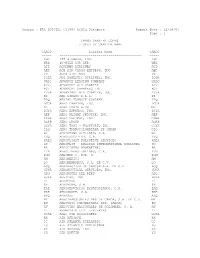

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC. -

Flying Tiger Line, Inc. V. Los Angeles County Roger J

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Opinions The onorH able Roger J. Traynor Collection 12-16-1958 Flying Tiger Line, Inc. v. Los Angeles County Roger J. Traynor Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/traynor_opinions Recommended Citation Roger J. Traynor, Flying Tiger Line, Inc. v. Los Angeles County 51 Cal.2d 314 (1958). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/traynor_opinions/409 This Opinion is brought to you for free and open access by the The onorH able Roger J. Traynor Collection at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Opinions by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 314 FLYING TIGER LINE, INC. tJ. COUNTY OF L. A. [51 C.2d [L. A. No. 24532. In Bank. Dec. 16, 1958.] THE FLYING TIGER LINE, INC. (a Corporation), Re spondent, v. THE COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES et al., Appellants. [1] Commerce-Taxation.-A county does not have power to assess an ad valorem property tax on the full value of aircraft that are regularly flown in interstate and foreign commerce and physically present in the county only during part of the period for which the tax is collected. [2] Id.-Taxation.-The rule permitting taxation of aircraft by two or more states on an apportioned basis precludes taxation on all the property by the state of domicile. [8] Id.-Taxation.-A taxpayer resisting an ad valorem tax on personal property based on an unapportioned assessment does not have the burden of showing that other states have actually imposed a tax on such property; he is entitled to an assess ment on an apportionment basis if the record shows that he was, during a tax year, receiving substantial benefits and protection in more than one state. -

(Josress) Volume: 3 Issue: 2 ISSN: 2459-0029

Journal of Strategic Research in Social Science Year: 2017 (JoSReSS) Volume: 3 www.josress.com Issue: 2 ISSN: 2459-0029 The History of Human Factors in the Airplane Accidents Mukadder İĞDİ ŞEN1 Keywords Abstract Human factors, aircraft Training on human factors in aviation is mandated by national and crashes, psychology, international Civil Aviation Organizations and Authorities. Human factors are aviation, education. the basic elements of all activities of cockpit and cabin crew and the aircraft maintenance technical team. For this purpose, human factors subject are Article History discussed in detail in terms of social psychology, factors affecting Received performance, physical environment, tasks, communication, human error, 15 May, 2017 hazards in the workplace. In order to minimize the risks that sector Accepted employees may cause in aircraft crashes, the authorities have been made a 18 Jun, 2017 legal obligation to train human factors in detail every two years. Uçak Kazalarında İnsan Faktörlerinin Dünü ve Bugünü Anahtar Kelimeler Özet İnsan faktörleri, uçak Ulusal ve uluslararası Sivil Havacılık Organizasyonları ve Otoriteleri kazaları, psikoloji, havacılık, tarafından, havacılıkta insan faktörleri ile ilgili eğitim, zorunlu tutulmuştur. eğitim. İnsan faktörleri; kokpit ve kabin ekibinin, uçak bakım teknik ekibinin bütün faaliyetlerinin temel unsurudur. Bu maksatla insan faktörleri konusu sosyal Makale Geçmişi psikoloji, performansa etki eden faktörler, fiziksel çevre, görevler, iletişim, Alınan Tarih insan hatası, işyerindeki tehlikeler açılarından detaylı olarak ele alınmaktadır. 15 May, 2017 Sektör çalışanlarının uçak kazalarına sebep olabilecekleri riskleri minimuma Kabul Tarihi indirmek için her iki yılda bir detaylı olarak insan faktörleri eğitimine tabii 18 Jun, 2017 tutulması otoritelerce yasal bir zorunluluk haline getirilmiştir. 1. Giriş Türk Dil Kurumuna göre “can veya mal kaybına, zararına neden olan kötü olay” kaza olarak tanımlanır. -

AIR AMERICA - COOPERATION with OTHER AIRLINES by Dr

AIR AMERICA - COOPERATION WITH OTHER AIRLINES by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 23 August 2010, last updated on 24 August 2015 1) Within the family: The Pacific Corporation and its parts In a file called “Air America - cooperation with other airlines”, one might first think of Civil Air Transport Co Ltd or Air Asia Co Ltd. These were not really other airlines, however, but part of the family that had been created in 1955, when the old CAT Inc. had received a new corporate structure. On 28 February 55, CAT Inc transferred the Chinese airline services to Civil Air Transport Company Limited (CATCL), which had been formed on 20 January 55, and on 1 March 55, CAT Inc officially transferred the ownership of all but 3 of the Chinese registered aircraft to Asiatic Aeronautical Company Limited, selling them to Asiatic Aeronautical (AACL) for one US Dollar per aircraft.1 The 3 aircraft not transferred to AACL were to be owned by and registered to CATCL – one of the conditions under which the Government of the Republic of China had approved the two-company structure.2 So, from March 1955 onwards, we have 2 official owners of the fleet: Most aircraft were officially owned by Asiatic Aeronautical Co Ltd, which changed its name to Air Asia Co Ltd on 1 April 59, but three aircraft – mostly 3 C-46s – were always owned by Civil Air Transport Co Ltd. US registered aircraft of the family like C-54 N2168 were officially owned by the holding company – the Airdale Corporation, which changed its name to The Pacific Corporation on 7 October 57 – or by CAT Inc., which changed its name to Air America on 3 31 March 59, as the organizational chart of the Pacific Corporation given below shows. -

Aircraft Accident Report, Near Collision of Delta Air Lines, Inc

Aircraft Accident Report, Near Collision of Delta Air Lines, Inc. Boeing 727-200, N467DA, and Flying Tiger, Inc. Boeing 747-F, N804FT, O'Hare International Airport, Chicago, Illinois, February 15, 1979 Micro-summary: This Boeing 727 entered a runway being used by a landing Boeing 747. Event Date: 1979-02-15 at 0911 CST Investigative Body: National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), USA Investigative Body's Web Site: http://www.ntsb.gov/ Cautions: 1. Accident reports can be and sometimes are revised. Be sure to consult the investigative agency for the latest version before basing anything significant on content (e.g., thesis, research, etc). 2. Readers are advised that each report is a glimpse of events at specific points in time. While broad themes permeate the causal events leading up to crashes, and we can learn from those, the specific regulatory and technological environments can and do change. Your company's flight operations manual is the final authority as to the safe operation of your aircraft! 3. Reports may or may not represent reality. Many many non-scientific factors go into an investigation, including the magnitude of the event, the experience of the investigator, the political climate, relationship with the regulatory authority, technological and recovery capabilities, etc. It is recommended that the reader review all reports analytically. Even a "bad" report can be a very useful launching point for learning. 4. Contact us before reproducing or redistributing a report from this anthology. Individual countries have very differing views on copyright! We can advise you on the steps to follow. Aircraft Accident Reports on DVD, Copyright © 2006 by Flight Simulation Systems, LLC All rights reserved.