Chapter 1. Before Our Founding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANA and Japan Airlines Formulate New Accessibility Guidelines to Ensure a Safe and Comfortable Journey for All Passengers During COVID-19 Crisis

ANA and Japan Airlines Formulate New Accessibility Guidelines to Ensure a Safe and Comfortable Journey for All Passengers during COVID-19 crisis Airlines jointly introduce new measures in providing assistance involving physical contact; strengthen initiatives to ensure hand disinfection and sterilization and approaching diagonally or from the side to prevent direct transmission. New measures strengthen the ability to provide timely information for those with visual and/or hearing impairment. Carriers are committed to improving communication measures, and while masks are essential in protecting one’s health, the carriers will provide visual aids at the airport to overcome the difficulties that masks create for the hearing impaired. TOKYO, October 26, 2020 – All Nippon Airways (ANA) and Japan Airlines (JAL), under the direct supervision of The Nippon Care-Fit Education Institute, today announced a new accessibility guideline for customers requesting special assistance at the airport and during flights and airline employees to ensure a safe and accessible journey when traveling by air during COVID-19 crisis. The guideline follows the International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) “Guidance on Accessible Air Travel in Response to COVID-19”, which lays out the basic principles for airlines to follow on special assistance requests, and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) of Japan’s guideline on measures of communication-based assistance for customers need special assistance. Based on the jointly announced new accessibility guidelines, ANA and JAL will act responsibly and respond to the needs of the traveling public, while strengthening efforts to prevent the spread of COVID- 19. Both carriers seek to provide a safe, secure and accessible travel experience. -

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

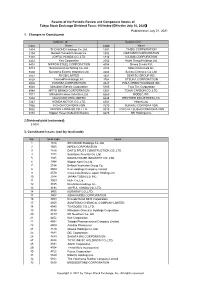

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

4Th Quarter 2016 Report

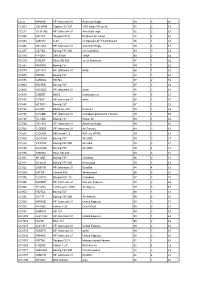

4th Quarter 2016 Report Fly Quiet Program Chicago O’Hare International Airport Visit the O’Hare Noise Webpage on the Internet at www.flychicago.com/ORDNoise th 4 Quarter 2016 Report Background On June 17, 1997, the City of Chicago announced that airlines operating at O’Hare International Airport had agreed to use designated noise abatement flight procedures in accordance with the Fly Quiet Program. The Fly Quiet Program was implemented in an effort to further reduce the impacts of aircraft noise on the surrounding neighborhoods. The Fly Quiet Program is a voluntary program that encourages pilots and air traffic controllers to use designated nighttime preferential runways and flight tracks developed by the Chicago Department of Aviation in cooperation with the O'Hare Noise Compatibility Commission, the airlines, and the air traffic controllers. These preferred routes direct aircraft over less-populated areas, such as forest preserves, highways, as well as commercial and industrial areas. As part of the Fly Quiet Program, the Chicago Department of Aviation prepares a Quarterly Fly Quiet Report. This report is shared with Chicago Department of Aviation officials, the O'Hare Noise Compatibility Commission, the airlines, and the general public. The Fly Quiet Report contains detailed information regarding nighttime runway use, flight operations, flight tracks, and noise complaints and 24-hour tracking of ground run-ups. The data presented in this report is compiled from the Airport Noise Management System (ANMS) and airport operation logs. Operations O’Hare has seven runways that are all utilized at different times depending on a number of conditions including weather, airfield pavement and construction activities and air traffic demand. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE Japan ESG Low Carbon Select Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country Constituent Index weight (%) Country ABC-Mart 0.01 JAPAN Ebara 0.17 JAPAN JFE Holdings 0.04 JAPAN Acom 0.02 JAPAN Eisai 1.03 JAPAN JGC Corp 0.02 JAPAN Activia Properties 0.01 JAPAN Eneos Holdings 0.05 JAPAN JSR Corp 0.11 JAPAN Advance Residence Investment 0.01 JAPAN Ezaki Glico 0.01 JAPAN JTEKT 0.07 JAPAN Advantest Corp 0.53 JAPAN Fancl Corp 0.03 JAPAN Justsystems 0.01 JAPAN Aeon 0.61 JAPAN Fanuc 0.87 JAPAN Kagome 0.02 JAPAN AEON Financial Service 0.01 JAPAN Fast Retailing 3.13 JAPAN Kajima Corp 0.1 JAPAN Aeon Mall 0.01 JAPAN FP Corporation 0.04 JAPAN Kakaku.com Inc. 0.05 JAPAN AGC 0.06 JAPAN Fuji Electric 0.18 JAPAN Kaken Pharmaceutical 0.01 JAPAN Aica Kogyo 0.07 JAPAN Fuji Oil Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Kamigumi 0.01 JAPAN Ain Pharmaciez <0.005 JAPAN FUJIFILM Holdings 1.05 JAPAN Kaneka Corp 0.01 JAPAN Air Water 0.01 JAPAN Fujitsu 2.04 JAPAN Kansai Paint 0.05 JAPAN Aisin Seiki Co 0.31 JAPAN Fujitsu General 0.01 JAPAN Kao 1.38 JAPAN Ajinomoto Co 0.27 JAPAN Fukuoka Financial Group 0.01 JAPAN KDDI Corp 2.22 JAPAN Alfresa Holdings 0.01 JAPAN Fukuyama Transporting 0.01 JAPAN Keihan Holdings 0.02 JAPAN Alps Alpine 0.04 JAPAN Furukawa Electric 0.03 JAPAN Keikyu Corporation 0.02 JAPAN Amada 0.01 JAPAN Fuyo General Lease 0.08 JAPAN Keio Corp 0.04 JAPAN Amano Corp 0.01 JAPAN GLP J-REIT 0.02 JAPAN Keisei Electric Railway 0.03 JAPAN ANA Holdings 0.02 JAPAN GMO Internet 0.01 JAPAN Kenedix Office Investment Corporation 0.01 JAPAN Anritsu 0.15 JAPAN GMO Payment Gateway 0.01 JAPAN KEWPIE Corporation 0.03 JAPAN Aozora Bank 0.02 JAPAN Goldwin 0.01 JAPAN Keyence Corp 0.42 JAPAN As One 0.01 JAPAN GS Yuasa Corp 0.03 JAPAN Kikkoman 0.25 JAPAN Asahi Group Holdings 0.5 JAPAN GungHo Online Entertainment 0.01 JAPAN Kinden <0.005 JAPAN Asahi Intecc 0.01 JAPAN Gunma Bank 0.01 JAPAN Kintetsu 0.03 JAPAN Asahi Kasei Corporation 0.26 JAPAN H.U. -

Factset-Top Ten-0521.Xlsm

Pax International Sustainable Economy Fund USD 7/31/2021 Port. Ending Market Value Portfolio Weight ASML Holding NV 34,391,879.94 4.3 Roche Holding Ltd 28,162,840.25 3.5 Novo Nordisk A/S Class B 17,719,993.74 2.2 SAP SE 17,154,858.23 2.1 AstraZeneca PLC 15,759,939.73 2.0 Unilever PLC 13,234,315.16 1.7 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,046,820.57 1.6 L'Oreal SA 10,415,009.32 1.3 Schneider Electric SE 10,269,506.68 1.3 GlaxoSmithKline plc 9,942,271.59 1.2 Allianz SE 9,890,811.85 1.2 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd. 9,477,680.83 1.2 Lonza Group AG 9,369,993.95 1.2 RELX PLC 9,269,729.12 1.2 BNP Paribas SA Class A 8,824,299.39 1.1 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. 8,557,780.88 1.1 Air Liquide SA 8,445,618.28 1.1 KDDI Corporation 7,560,223.63 0.9 Recruit Holdings Co., Ltd. 7,424,282.72 0.9 HOYA CORPORATION 7,295,471.27 0.9 ABB Ltd. 7,293,350.84 0.9 BASF SE 7,257,816.71 0.9 Tokyo Electron Ltd. 7,049,583.59 0.9 Munich Reinsurance Company 7,019,776.96 0.9 ASSA ABLOY AB Class B 6,982,707.69 0.9 Vestas Wind Systems A/S 6,965,518.08 0.9 Merck KGaA 6,868,081.50 0.9 Iberdrola SA 6,581,084.07 0.8 Compagnie Generale des Etablissements Michelin SCA 6,555,056.14 0.8 Straumann Holding AG 6,480,282.66 0.8 Atlas Copco AB Class B 6,194,910.19 0.8 Deutsche Boerse AG 6,186,305.10 0.8 UPM-Kymmene Oyj 5,956,283.07 0.7 Deutsche Post AG 5,851,177.11 0.7 Enel SpA 5,808,234.13 0.7 AXA SA 5,790,969.55 0.7 Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

ANA and NCA Agree to a Strategic Business Partnership ~To Continue Contributing to Japan’S Economic Development ~

ANA and NCA Agree to a Strategic Business Partnership ~To continue contributing to Japan’s economic development ~ TOKYO, March 1, 2018 – All Nippon Airways (ANA) and Nippon Cargo Airlines (NCA) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to enhance both, the service and the corporate value of the two airlines by building a strategic business partnership. The three key elements of this partnership which will give added value to ANA’s and NCA’s customers, and will provide them with seamless logistics experiences are: 1. Code Share Within the first half of the fiscal year 2018, ANA and NCA plan to add codeshares to each other’s flights(*). The codeshares will offer a broad network of flights and a wider range of choices to the partner’s customers, allowing seamless and convenient connections with outstanding Japan-quality service, and especially leveraging the synergy effect of ANA’s Boeing 767 operation to China and Asia, and NCA’s Boeing 747 freighter operation to North America and Europe. ANA’s plans to introduce Boeing 777 freighters will further increase the customer choice. 2. Block Space Through this partnership, the two airlines plan to expand the existing interline and block space agreement, with the aim to effectively utilize each other’s cargo space and provide a reliable and convenient connection service. 3. Maintenance Support Finally, the MOU includes a maintenance support agreement, by which ANA will allocate maintenance resources to support NCA’s operation. The agreement will enable active sharing of knowledge and enhancement of the technical abilities of both carriers. With this new partnership, ANA and NCA hope to provide their customers access to a large global freight network, highest quality of service, and convenient and flexible choices, responding to the growing demand. -

New Expanded Joint Venture

Press Release The Power of Choice for Cargo Customers as Air France-KLM, Delta and Virgin Atlantic launch trans-Atlantic Joint Venture AMSTERDAM/PARIS, ATLANTA and LONDON: February 3rd, 2020 – Air France-KLM Cargo, Delta Air Lines Cargo and Virgin Atlantic Cargo are promising cargo customers more connections, greater shipment routing flexibility, improved trucking options, aligned services and innovative digital solutions with the launch of their expanded trans-Atlantic Joint Venture (JV). The new partnership, which represents 23% of total trans-Atlantic cargo capacity or more than 600,000 tonnes annually, will enable the airlines to offer the best-ever customer experience, and a combined network of up to 341 peak daily trans-Atlantic services – a choice of 110 nonstop routes with onward connections to 238 cities in North America, 98 in Continental Europe and 16 in the U.K. More choice and convenience for customers Customers will be able to leverage an enhanced network built around the airlines’ hubs in Amsterdam, Atlanta, Boston, Detroit, London Heathrow, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York-JFK, Paris, Seattle and Salt Lake City. It creates convenient nonstop or one-stop connections to every corner of North America, Europe and the U.K., giving customers the added confidence of delivery schedules being met by a wide choice of options. The expanded JV enables greater co-operation between the airlines, focused on delivering world class customer service and reliability on both sides of the Atlantic achieved through co-located facilities, joint trucking options as well as seamless bookings and connected service recovery. The airlines already co-locate at warehouses in key U.S., U.K. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Oneworld, Codeshare and Other Partner Airlines

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT ONEWORLD, CODESHARE AND OTHER PARTNER AIRLINES 1. What will happen to AA’s participation in the oneworld Alliance and its relationships with its codeshare partners or other partner airlines? We expect our participation in oneworld and our relationships with our other partners to remain unchanged. 2. Can I still accrue miles and redeem mileage awards through oneworld and American's frequent flyer air partners? Yes, we expect our partnerships with airlines such as British Airways, Cathay Pacific, Finnair, Iberia, Japan Airlines (JAL), LAN, Malév, Qantas, Royal Jordanian and S7 Airlines and others remain unchanged as a result of the Chapter 11 filing. 3. Will my elite status with AAdvantage still be recognized by oneworld Alliance partners? Yes, we expect that your elite status with AAdvantage will continue to be recognized by our oneworld partners, and that the benefits you receive when flying with them will not change as a result of the Chapter 11 filing. 4. Will there be a reduction of routes that AA currently offers through oneworld and its codeshare partners? We remain deeply committed to meeting your travel needs with the same standards of safe, secure and reliable service, and intend to maintain a strong presence in domestic and international markets. As we and all airlines routinely do, we will continue to evaluate our operations and service, assuring that our network is as efficient and productive as possible. 5. Will AA’s airline partners continue to honor their ticket reservation and baggage transfer commitments? Yes. We expect that all benefits with partner airlines will remain intact. -

Skyteam Global Airline Alliance

Annual Report 2005 2005 Aeroflot made rapid progress towards membership of the SkyTeam global airline alliance Aeroflot became the first Russian airline to pass the IATA (IOSA) operational safety audit Aeroflot annual report 2005 Contents KEY FIGURES > 3 CEO’S ADDRESS TO SHAREHOLDERS> 4 MAIN EVENTS IN 2005 > 6 IMPLEMENTING COMPANY STRATEGY: RESULTS IN 2005 AND PRIORITY TASKS FOR 2006 Strengthening market positions > 10 Creating conditions for long-term growth > 10 Guaranteeing a competitive product > 11 Raising operating efficiency > 11 Developing the personnel management system > 11 Tasks for 2006 > 11 AIR TRAFFIC MARKET Global air traffic market > 14 The passenger traffic market in Russia > 14 Russian airlines: main events in 2005 > 15 Market position of Aeroflot Group > 15 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Governing bodies > 18 Financial and business control > 23 Information disclosure > 25 BUSINESS IN 2005 Safety > 28 Passenger traffic > 30 Cargo traffic > 35 Cooperation with other air companies > 38 Joining the SkyTeam alliance > 38 Construction of the new terminal complex, Sheremetyevo-3 > 40 Business of Aeroflot subsidiaries > 41 Aircraft fleet > 43 IT development > 44 Quality management > 45 RISK MANAGEMENT Sector risks > 48 Financial risks > 49 Insurance programs > 49 Flight safety risk management > 49 PERSONNEL AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Personnel > 52 Charity activities > 54 Environment > 55 SHAREHOLDERS AND INVESTORS Share capital > 58 Securities > 59 Dividend history > 61 Important events since December 31, 2005 > 61 FINANCIAL REPORT Statement