LCD-76-214 Review of the Military Airlift Command's Use of Chartered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

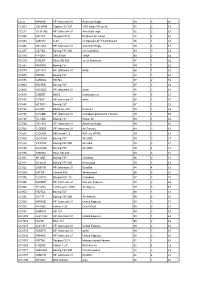

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON October 31, 197 5 MEMORANDUM TO: JACK MARSH FROM: RUSS ROURKE I discussed the Ft. Dix situation with Rep. Ed Forsythe again. As you may know, I reviewed the matter with Marty Hoffman at noon yesterday, and with Col. Kenneth Bailey several days ago. Actually, I exchanged intelligence information with him. Hoffman and Bailey advised me that no firm decision has as yet been made with regard to the retention of the training function at Dix. On Novem ber 5, Marty Hotfman will receive a briefing by Army staff on pos sible "back fill'' organizations that may be available to go to Dix in the event the training function moves out. -

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

July/August 2000 Volume 26, No

Irfc/I0 vfa£ /1 \ 4* Limited Edition Collectables/Role Model Calendars at home or in the office - these photo montages make a statement about who we are and what we can be... 2000 1999 Cmdr. Patricia L. Beckman Willa Brown Marcia Buckingham Jerrie Cobb Lt. Col. Eileen M. Collins Amelia Earhart Wally Funk julie Mikula Maj. lacquelyn S. Parker Harriet Quimby Bobbi Trout Captain Emily Howell Warner Lt. Col. Betty Jane Williams, Ret. 2000 Barbara McConnell Barrett Colonel Eileen M. Collins Jacqueline "lackie" Cochran Vicky Doering Anne Morrow Lindbergh Elizabeth Matarese Col. Sally D. Woolfolk Murphy Terry London Rinehart Jacqueline L. “lacque" Smith Patty Wagstaff Florene Miller Watson Fay Cillis Wells While They Last! Ship to: QUANTITY Name _ Women in Aviation 1999 ($12.50 each) ___________ Address Women in Aviation 2000 $12.50 each) ___________ Tax (CA Residents add 8.25%) ___________ Shipping/Handling ($4 each) ___________ City ________________________________________________ T O TA L ___________ S ta te ___________________________________________ Zip Make Checks Payable to: Aviation Archives Phone _______________________________Email_______ 2464 El Camino Real, #99, Santa Clara, CA 95051 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL WOMEN PILOTS (ISSN 0273-608X) 99 NEWS INTERNATIONAL Published by THE NINETV-NINES* INC. International Organization of Women Pilots A Delaware Nonprofit Corporation Organized November 2, 1929 WOMEN PILOTS INTERNATIONAL HEADQUARTERS Box 965, 7100 Terminal Drive OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFTHE NINETY-NINES® INC. Oklahoma City, -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Theater Airlift Lessons from Kosovo

Theater Airlift Lessons from Kosovo by Lt Col Rowayne A. Schatz, USAF This basic doctrine presents the guiding principles of our Service and our view of the opportunities of the future… As airmen, we must understand these ideas, we must cultivate them and, importantly, we must debate and refine these ideas for the future.1 General Michael E. Ryan Chief of Staff, USAF Operation Allied Force, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military operation to compel Serbia to cease hostilities against ethnic Albanians in Kosovo and allow a peacekeeping presence on the ground, was the first major war in history fought exclusively with air power. NATO air forces flew over 38,000 sorties from 24 March through 9 June 1999 to allow NATO to achieve its political objectives in Kosovo.2 Although you may not have heard or read much about them, air mobility forces were key to the success of the air war over Serbia. The air mobility team moved enough airmen and equipment to increase the number of air expeditionary wings in Europe from three to ten, provided aid directly to thousands of Kosovar refugees, and deployed a large US Army contingent to Albania—all at the same time. In the words of Colonel Scott Gray, the USAFE Assistant Director of Operations during Operation Allied Force, "This was a phenomenal success, enabling the forces which forced Milosevic to back down while sustaining the refugees he created until they were able to go home.3 According to AFDD1, "Air and space doctrine is an accumulation of knowledge gained primarily from the study and analysis of experience, which may include actual combat or contingency operations as well as equipment tests or exercises."4 I am a firm believer that doctrine is key to warfighting. -

The Usaf C-17 Fleet: a Strategic Airlift Shortfall?

AU/ACSC/0265/97-03 THE USAF C-17 FLEET: A STRATEGIC AIRLIFT SHORTFALL? A Research Paper Presented To The Research Department Air Command and Staff College In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements of ACSC by Maj. Randall L. Long March 1997 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government or the Department of Defense. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................iv LIST OF TABLES ..........................................................................................................v PREFACE......................................................................................................................vi ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................. vii STRATEGIC AIRLIFT TODAY.....................................................................................1 Introduction and Problem Definition............................................................................1 Thesis Statement.........................................................................................................3 Overview ....................................................................................................................3 STRATEGIC AIRLIFT -

MG Patterson's

U N I T E D S T A T E S A I R F O R C E MAJOR GENERAL ROBERT B. PATTERSON Retired Oct. 1, 1989. Major General Robert B. Patterson is commander of Military Airlift Command's 23rd Air Force, Hurlburt Field, Fla., and commander of Air Force Special Operations Command. General Patterson was born in Mebane, N.C. He attended public schools in Chapel Hill, N.C., and graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1956. The general received a master's degree in business administration from Webster College and is a graduate of Columbia University's executive program in business administration. He completed Armed Forces Staff College in 1971 and Air War College in 1976. He entered the Air Force in August 1956 and received his pilot wings at Vance Air Force Base, Okla., in October 1957. His first operational assignment was to the 31st Air Rescue Squadron at Clark Air Base, Philippines. In 1960 he transferred to Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, as aide-de-camp to the Military Training Center commander. From 1963 to 1966 he served as special assistant to the air deputy of Allied Forces Northern Europe in Oslo, Norway. Returning to the United States, General Patterson joined the 39th Tactical Airlift Squadron of the 317th Tactical Airlift Wing, Lockbourne (now Rickenbacker) Air Force Base, Ohio. He departed Lockbourne in March 1970 to serve at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, as an AC-130 gunship pilot in the 16th Special Operations Squadron of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing. -

A Brief History of Air Mobility Command's Air Mobility Rodeo, 1989-2011

Cover Design and Layout by Ms. Ginger Hickey 375th Air Mobility Wing Public Affairs Base Multimedia Center Scott Air Force Base, Illinois Front Cover: A rider carries the American flag for the opening ceremonies for Air Mobility Command’s Rodeo 2009 at McChord AFB, Washington. (US Air Force photo/TSgt Scott T. Sturkol) The Best of the Best: A Brief History of Air Mobility Command’s Air Mobility Rodeo, 1989-2011 Aungelic L. Nelson with Kathryn A. Wilcoxson Office of History Air Mobility Command Scott Air Force Base, Illinois April 2012 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: To Gather Around ................................................................................................1 SECTION I: An Overview of the Early Years ...........................................................................3 Air Refueling Component in the Strategic Air Command Bombing and Navigation Competition: 1948-1986 ...................................................................4 A Signature Event ............................................................................................................5 The Last Military Airlift Command Rodeo, 1990 ...........................................................5 Roundup ................................................................................................................8 SECTION II: Rodeo Goes Air Mobility Command ..................................................................11 Rodeo 1992 ......................................................................................................................13 -

Federal Aviation Agency

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 30 • NUMBER 57 Thursday, March 25, 196S • Washington, D.C. Pages 3851-3921 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Comptroller of the Currency Consumer and Marketing Service Economic Opportunity Office Engineers Corps Federal Aviation Agency Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Immigration and Naturalization Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau National Shipping Authority Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Veterans Administration Wage and Hour Division Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Subscriptions Now Being Accepted S L I P L A W S 89th Congress, 1st Session 1965 Separate prints of Public Laws, published immediately after enactment, with marginal annotations and legislative history references. Subscription Price: / $12.00 per Session Published by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 20402 i & S A Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on^ on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Regi . ^ ay0Iiai FEDERAL®REGISTER LI address Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail adore ^ th0 Area Code 202 Phone 963-3261 fcy containe< -vwiTEo-WilTED’ nrcmvesArchives jsuuamg,Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to tnethe authority coni Admin- Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935' (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C., ch. 8B b under regulations prescribedIbed by thetne ent istrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (1 CFR Ch. -

The Appearance of Local Business Names Does NOT Imply Federal Endorsements. All Information to Include Addresses and Telephone Numbers Are Subject to Change

The appearance of local business names does NOT imply federal endorsements. All information to include addresses and telephone numbers are subject to change. Please call the business to confirm their operation hours. Please do not remove this directory from your room. General Information A Letter From The General Manager Air Force Inns Promise Safety & Security Bomb Threat Force Protection Hurricane & Tornado Information Beach Flag Warnings Wild Life Off-Limits Restriction Listing Lodging Information Guest Responsibilities Room Rates Service Fees Guest Services and Information Energy Conservation Telephone Information Telephone Dialing Instructions High Speed Internet Information Quick Reference Base Facilities Base Community Activities Base Chapel Information Laundry and Dry Cleaning Information Kennel Listing On and Off Base Hospital Information Dining Information On-Base Dining Establishments Off-Base Dining Establishments www.myhurlburt.com Maps FSS Map Building 90502 Building 90507 Building 90918 TLFs DVQs Area Attractions Area Attractions TV/Radio Information Television Services & Channel Guide Emerald Coast Radio Directory Transportation Base Taxi Commercial Taxi Services Biographies Hurlburt Field Biographies www.myhurlburt.com WELCOME LODGING GUESTS Dear Valued Guest, We are pleased you have chosen to stay at the Commando Inn on Hurlburt Field as our guest and we look forward to making your stay comfortable, safe and pleasant. On behalf of the 1st Special Operations Wing commander, 1st Special Operations Mission Support Group commander, 1st Special Operations Force Support Squadron commander, and the lodging staff, we welcome you to Hurlburt Field and the Commando Inn. This directory has been created to assist you in discovering what Hurlburt Field and the surrounding areas have to offer. -

Mcchord AFB Rental Car: Mr

The Honorable Philip Coyle,DCN: 5886BRAC Commissioner @ The Honorable James Bilbray, BRAC Commissioner \A? 25 May 2005 "1 4cqp 11~ Wednesday, 25 May 2005 DRESS: UOD 0730 Depart lod~ingen route to McChord AFB Rental Car: Mr. Coyle Mr. Bilbray Ms. Schmidt 0815 Arrive DV Loun~e(greet side) for Wing Mission Brief Escorted by: Capt Adam Digger DiGerolamo, 62 AWICCP Met by: TSgt Donald Don Kusky, 62 AWICCP TSgt Mariah Tiedeman, 62 AWICCP Attendees: Col Frederick Rick Martin, 62 AWICV Col Eric Crabtree, 446 AWICC Col Steven Steve Arcpiette, 62 AWIDS Col Thomas Tim McCauley, 62 MSGICC Col Joseph JC Crowinover, 62 MSGICC Lt Col John S~hmed~ake,62 AWIXP Mr. Coyle Mr. Bilbray Ms. Schmidt 0900 DV Lounge to DV-1 for static display Briefers: Maj Richard Rich Fields - Pilot TSgt Chris Beckwithi - Loadmaster 1Lt Claudia Gortva - Base Ops SMSgt James Jim Robson - Tower p. 1 Mr. Coyle The Honorab'le Philip Coyle, BRAC Commissioner The Honorabk James Bilbray, BRAC Commissioner 25 May 2005 0945 Depart DV-1 for Windshield Tour Surrey Bus: Col Martin Col Arquiette Mr. Coyle Mr. Bilbray Ms. Schmidt Col Joseph Joe Bradbury, WADSIDS Col Rebecca Becky Garcia, 62 MXGICC Col Crownover Col McCauley Lt Col Schmedake Lt Col Van Fuller, 6:2 CESICC Driver: A 1 C Randy Henson, 62 LRSILGRVO Driving; bv: Tour of flight line, Home Station Check (Hangar 1 & 2), Building 100, STS 1000 Arrive CE for briefing; on Mission and Deployments Met by: ? ? ? Briefer: Lt Col Fuller 1015 Depart CE to continue windshield tour Driving by: WADS, Golf Course, Community Center 1025 Arrive Medical Grolup for briefing in Hansen Suite Met By: Col Lori Heim, 62 MDGICD Briefer: Col McCauley 1125 Depart Medical Group en route to Northwest Connection, Fireside Lounge p.