Hope in the Future: the Experiences of Youth Under Communism, the Transition to Democracy, and the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VI. L'esprit Scout

250 réponses à vos questions sur le scoutisme Bruno RONDET, François-Xavier NÈVE, Hervé TABOURIN Sommaire p.3 Q.1. Invitation : venez et voyez — un secret partagé ? p.11 Q.2. L’esprit scout, ne le voit-on pas venir de loin ? p.12 I. Les récits fondateurs Q.3. Baden-Powell, un officier impérialiste ? p.13 Q.4. Le siège de Mafeking (Afrique du sud) en 1899-1900 : légende ou Histoire ? p.14 Q.5. Brownsea, le premier camp scout : germe prophétique ? p.15 Q.6. Quel fut le programme de ce premier camp ? p.15 Q.7. BP s’est-il marié ? p.16 Q.8. « éclaireurs » ou « Boy-Scouts » : d’où vient ce nom ? p.17 Q.9. Le scout est-il pacifiste ou militariste ? Que voulait BP ? p.18 Q.10. Qu’entendait BP par fraternité scoute ? p.18 Q.11. Comment cette fraternité scoute pouvait-elle se développer à travers les frontières ? p.19 Q.12. Jamboree, jamboree ? ! 20 Q.13. Y a-t-il eu d’autres jamborees depuis celui de 1920 ? p.21 Q.14. Qu’est-ce qu’un Eurojam ? p.22 Q.15. Qui était Roland Philipps, l’adjoint de BP ? p.22 Q.16. Que doit le louvetisme à Vera Barclay ? p.23 Q.17. Que vient faire chez les scouts Pierre de Coubertin, l’inventeur des Jeux olympiques modernes ? p.24 Q.18. Le maréchal Lyautey était-il scout ? p.25 Q.19. Jean Corbisier (1869-1928), « chef scout » catholique belge : un sanglier pionnier ? p.26 Q.20. Gilwell, la Mecque des scouts ? p.26 Q.21. -

International Catholic Conference of Scouting Celebrates 100 Years of Service to the Worldwide Scouting Movement

VOLUME 29 NO. 4— WINTER 2020 International Catholic Conference of Scouting celebrates 100 years of service to the worldwide Scouting Movement and became a Jesuit novice in By Phil Krajec 1900. While preparing for his NCCS International Committee ordination, he became interested Chair in the Scouting movement that was gaining strength in When the founder of the the United Kingdom. However, worldwide Scout Movement many in religious circles were Lord Robert Baden-Powell was critical of Scouting, and he ob- asked where religion came into tained permission from his supe- Scouting, he replied, “It does not riors to investigate the move- come in at all. It is already ment. He attended a scout rally there.” in London in September 1913, Almost from the beginning of where he met Baden-Powell him- Scouting in 1907, there were self. responsibility, dedication, educa- Catholic Scout troops. By the After meeting Baden-Powell, tion, and the natural world but also time Baden-Powell visited South Father Sevin wrote his classic included a spiritual component. America in 1909, Scouting had ocumentary study called Le Father Sevin was able to already started in Argentina and demonstrate to skeptics that Scout- Chile. In 1910, the Boy Scouts ing could meld Baden- of America was incorporated Powell’s model and the Chris- and the first known Catholic tian Gospel. Baden-Powell said Scout Troop in the BSA was that no one turned his thoughts into formed in St. Paul, Minnesota. reality better than Jacques Sevin. Catholic troops formed in Bel- Father Sevin met Jean Corbisier gium in 1910 and in Austria in of Belgium and Count Mario Ga- 1912. -

The Explorer Vol. 3 – Lent 2016

LENT 2016 THE EXPLORER Volume 3 A PERIODICAL OF THE FEDERATION OF NORTH-AMERICAN LENTEN PENANCE FALLACY OF THE EXPLORERS. LETTER TO THE FNE FOR EXPLORERS WEEK: SCOUTING IS LENT 2016 FR. LAWRENCE LEW, BR. ANDRE-MARIE UN-CATHOLIC O.P M.I.C.M MOUNT DAVID SMITH, DEPUTY MONADNOCK FNE GROUP LEADER, NORTH STAR FNE THE EXPLORER them. A few months later, God sent four French Dear brothers and sisters, my Explorers to our student parish and one of them fellow Explorers, asked me if he could start a Wayfarer Explorers group. I agreed to support and help him and from God’s Providence leads us in there began an adventure in what Ven. Fr. Jacques Ways that are so wonderful Sevin SJ called ‘Scoutisme’: Baden-Powell’s that if we trust Him we will be traditional Exploring animated with power of the led to places that surpass all Gospel of salvation. our dreams and desires and imaginings.Because Christ is The summer of 2014 I was invited to Eurojam in our Way and, following the Normandy (France) as a Chaplain to a Truth that He Camp of about 200 boys, and I was so teaches us Our life in the FNE amazed by what I saw: independent through His Movement as boys and girls who were Holy Church, capable of so much more than society we will be led to Explorers is a told us children and teenagers could eternal Life, to “that Camp of rest and preparation for that do. They were full of life – the joy where Christ has pitched His tent sublime Camp which “abundant life” that Jesus came to give and ours for all Eternity”. -

Inventario Archivio Asci

cop-controcop-costa ASCI 34x24 def8 conv:copertina ASCI 05/01/2011 19.34 Pagina 1 CENTRO DOCUMENTAZIONE AGESCI catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 pag int def6 conv:catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 04/01/2011 20.06 Pagina 2 catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 pag int def6 conv:catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 04/01/2011 20.06 Pagina 3 catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 pag int def6 conv:catalogo ASCI CD 17X24 04/01/2011 20.06 Pagina 4 SOMMARIO Una memoria ritrovata per la storia dello scautismo e del guidismo cattolici italiani, di Michele Pandolfelli 5 Il valore degli archivi di un’associazione come l’Agesci per la ricerca e la cultura del Paese, di Donato Tamblé 11 INVENTARIO Nota storico-archivistica 15 PRIMA ASCI Serie 1. Statuti, circa 1922-1923 23 Serie 2. Verbali, 1916-1924 24 Serie 3. Registri di protocollo, 1919-1921 25 Serie 4. Formazione capi, 1922 26 Serie 5. Internazionale, 1920-1928 27 Serie 6. Censimenti, registrazioni unità, soci, 1916-1928 29 sottoserie 1. Riepiloghi annuali, 1923-1928 29 sottoserie 2. Regioni, province, città, 1916-1928 30 1. Emilia-Romagna, 1918-1928 30 2. Friuli-Venezia Giulia, 1919-1928 37 3. Lazio, 1916-1928 38 4. Liguria, 1919-1927 43 5. Lombardia, 1916-1928 45 6. Marche, 1916-1928 55 7. Sardegna, 1917-1927 58 8. Sicilia, 1919-1927 63 9. Toscana, 1921-1928 68 10. Trentino-Alto Adige, 1922-1927 77 11. Umbria, 1923-1925 78 12. Veneto, 1920-1928 79 13. Colonie, 1922-1926 83 Serie 7. Stampa, 1922-1926 84 Serie 8. Amministrazione, 1918-1922 85 2 Archivio dell'Associazione scautistica cattolica italiana (Asci) SECONDA ASCI Sezione 1. -

A History of Youth Work

youthwork.book Page 3 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM A century of youth work policy youthwork.book Page 4 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM youthwork.book Page 5 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM A century of youth work policy Filip COUSSÉE youthwork.book Page 6 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia bvba Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be Filip Coussée A century of youth work policy Gent, Academia Press, 2008, ### pp. Opmaak: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 #### # D/2008/4804/### NUR ### U #### Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of vermenigvuldigd door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. youthwork.book Page 1 Wednesday, May 7, 2008 2:43 PM Table of Contents Chapter 1. The youth work paradox . 3 1.1. The identity crisis of youth work. 3 1.2. An international perspective . 8 1.3. A historical perspective. 13 1.4. An empirical perspective . 15 Chapter 2. That is youth work! . 17 2.1. New paths to social integration . 17 2.2. Emancipation of young people . 23 2.3. The youth movement becomes a youth work method. 28 2.4. Youth Movement incorporated by the Catholic Action. 37 2.5. From differentiated to inaccessible youth work . -

SPRINGFIELD LEADER • VAILSBURG LEADER 10-Tfi

!•>•- Thursday, June 13, 1974 .#•> Med School project gives jobs Greek convention to unskille^elfare mothers S^S^d <•*"•* Strir^^ ' • "* • "** Margaret D., mother of eight, is earning' headed the training program for the college. $5,800 a year.' |: ^ _ " > .''And you sense tilt difference it has made in /j S?T? Maritza R., mother of a three-year-old son. is^ hem, too, in their manner, and attitudes and in case of emergency The Zip Code earning $8,700 a year. The Eureka Chapter 52 of Newark will host the 43rd Fifth District convention of the _ __ camm Dolores M.. mother of a boy, is earning $5,500 A "tymiber of the women, who .had no American Hellenic Educational Progressive 376-0400 for Police Department for Springfield is •••--. • ••• •*-•'" .^"i^/^ a year. - '• t .-•• • diplomas>sace taking high school equivalency or First Aid Squed > s 1 Association this weekend. There wl|l be dtn- *• *• •..y.trfW-"'... *^ -".--" ^" :-. Ms. "D7, Ms. R_and Ms. M. are three of 32' tests, TysoiiNsaid. Others are already in ad- ' cing, sightseeing, swimming and a fashion" 376-7670 for Fire Department formerly untrained, unskilled and rarely vanced job thilning. One has completed' show, ending with the grand banquet, 07081 • emp'oyed welfare clients now holding down sociology courses at Kssex County College^ ; • tomorrow through Sunday at the Gateway . fulllime jobs at the College of Medicine and Downtowner Motor. Inn and the Robert Treat Publl.h.d Ev.-y Tkiuidoyby T>umof PublUhlng Co/p. Dentistry of flew Jersey (CMDNJ). 'Hotel.. Convention headquarters will be the 41 Mounlqln Ova., Sp.lngtl.lt), H.J. -

Inventaire Des Affiches Du CHBS Situation Au 1Er Novembre 2008 N

Inventaire des affiches du CHBS Situation au 1er novembre 2008 N° Origines Taille (hxl) Date Couleur Dessins-Textes-Photos Thème Divers 00001 FSC 120*84 sd C D-T Projet pédagogique Editeur resp. Joan Lismont 00002 FCS-GCB 90*60 sd NB P Activités Unité Ste Etienne et Unité guide Epheta 00003 OMMS 100*72 1975 C P-D-T Carte scoutisme mondial Photos de scouts, emblèmes et carte 00004 Jamboree 83*59 1991 C D-T Logo Jamboree 17th World Jamboree 00005 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Rangers : les trappeurs 00006 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France- Louveteau : la cuisine au camp, signé L. Vicomte 00007 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France- Pionniers : tours deux roues (vélo) 00008 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Louveteau : nature, forêt 00009 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Pionniers : code de la nature, signé L. Vicomte 00010 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Rangers : nature, eau, signé : sino id 00011 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Louveteau : secourisme 00012 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Pionniers : hygiène au camp, signé Michel Depons 00013 GSB 83*59 2007 C P-T Centenaire Invitation Jambe GSB 00014 FSC 83*60 2002 C P-T 90ème Invitation 90ème Les Scouts, biface, texte au verso 00015 France 80*60 1976 C D-T Techniques Scouts de France - Rangers : techniques de cirque 00016 SGP 85*62 1949 C D-T Fancy-fair BSB et GGB : fête breughelienne, Cre régional : P. -

1916-2016 Il Nostro Album Di Famiglia

PIERO GAVINELLI Piero Gavinelli L’autore ha pronunciato la Promessa il 10 aprile 1966 ed è stato capo di unità e di Gruppo, in ASCI e AGESCI, ESTRATTO DEL VOLUME dal 1970 al 1999. Ha ricoperto numerosi incarichi ai diversi livelli associativi ed è stato Capo campo nei corsi di formazione per capi per oltre venti anni. Dal 2002 al 2005 ha ricoperto il ruolo di Capo Scout d’Italia e attualmente è componente della redazione IL NOSTRO ALBUM DI FAMIGLIA della rivista scout per educatori “RS Servire” e del Comitato scientico del Centro Studi e Documentazione Scout “Mario Mazza”. 1916-2016 1916-2016 il nostro album PIERO GAVINELLI PIERO GAVINELLI di famiglia CENTO ANNI DI SCAUTISMO CATTOLICO IN ITALIA 100ASCI_copertina_DEF_STAMPA.indd 1 13/09/2016 21:26:46 Cento anni fa aveva inizio l’avventura dello scautismo cattolico in Italia che oggi è, numericamente, il maggiore presente nel Paese. È stata un’avventura che si è sviluppata, principalmente, attraverso una continuità ufficiale e storica incarnata prima nell’Asci, “ poi nell’Agi e, infine, nell’Agesci, con una presenza viva nel tessuto sociale ed ecclesiale che ha sempre espresso idee significative e, talvolta, profetiche. È stata l’avventura di molte persone ed è la storia di una coerenza fedele agli ideali della Legge scout. Questo non esaustivo “album di famiglia” racconta questi uomini e queste donne, momenti, situazioni e accadimenti che hanno caratterizzato questo secolo di vita e che ci rende orgogliosi di fare parte della “grande famiglia degli scout”. pag. 23 / foto 1 - uscita di esploratori appartenenti all’associazione Ragazzi Esploratori Cattolici Italiani (R.E.C.I.) / “Gioiosi” di Genova sulle alture circostanti la città pag. -

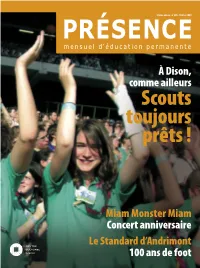

PRÉSENCE M E N S U E L D’ É D U C a T I O N P E R M a N E N T E

31ème année • n°305 • février 2009 PRÉSENCE m e n s u e l d’ é d u c a t i o n p e r m a n e n t e À Dison, comme ailleurs Scouts toujours prêts ! Miam Monster Miam Concert anniversaire Le Standard d’Andrimont centre culturel dison 100 ans de foot Sommaire 3 En ouverture | Jacky Lacroix PRÉSENCE 4 LE THÈME Les mouvements de jeunesse m e n s u e l d’ é d u c a t i o n p e r m a n e n t e 8 ACTU CULTURE Tiré à 6200 exemplaires, distribution toutes boîtes 11 Les Amis d’Adolphe Hardy • Rédaction et coordination : Jérôme Wyn 12 L’artiste du mois | Gilbert Zeyen • Mise en Page : Jean-Marc Daele • Photos : Pierre-Vincent « Pivi » Molinghen 15 Dans nos associations • Publicité : Evelyne Rouvroi 19 Agenda et coin du wallon Editeur responsable : Centre Culturel de Dison asbl 20 Informations communales Rue des Ecoles, 2 - 4820 Dison Tél. : 087/33 41 81 Fax : 087/35 24 84 e-mail : [email protected] www.ccdison.be Ce samedi 14 février, offrez à votre élu(e) votre coeur... en gâteau Rue Léopold 66/68 - 4820 DISON Bonne St-Valentin à Ouvert tous les jours de 12 à 15 h et de 18 à 23 h • Fermé le mercredi Rue de Rechain, 11 - 4820 Dison Tél./Fax : 087 39 88 90 Tél. : 087/33 39 21 - Fax : 087/33 39 22 tous les amoureux ! GSM : 0476 63 88 88 Heures d’ouverture : À midi : Lundi, mercredi, jeudi et vendredi de 7 h 30 à 18 h. -

The Word of the Federal Commissioner

CONTACT – KONTAKT - CONTATTO U.I.G.S.E. – F.S.E. 1 /2016 THE WORD OF THE FEDERAL COMMISSIONER Dear Sisters and Brothers in Scouting! It is a great joy for me that you just received the first edition of the new FSE journal CONTACT. To be honest, it is not completely new. Attilio Grieco who was the Federal President of our brotherhood agreed together with an international network of famous authors of our movement to revive this journal which has already served as an important means of communication from the year 1980 to 1984. The CONTACT journal brings us in touch – temporally, horizontally, and vertically. Temporally, because scouting is living from its traditions. Tradition is not a matter of keeping the ashes of former times, but keeping the initial fire burning. CONTACT brings you in touch with those who lighted the FSE fire, who let it grow, who carried its torch around Europe and recently to more and more countries across the ocean. Horizontally, because we are united among sisters and brothers living here and now through one Law and one Promise. For us brotherhood is not a matter of travelling and meeting breathlessly, but to share one method teaching ten thousands of girls and boys how to live together in truth and love. CONTACT lets you deepen our greatest pedagogical insights. Vertically, because our movement is consecrated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin Mary. There are no sisters and brothers if there is not a common father. Jesus Christ, the eternal Son of the Father, is the true head of our brotherhood. -

Scouting Round the World

SCOUTING ROUND THE WORLD SCOUTING ROUND THE WORLD JOHN S. WILSON BLANDFORD PRESS • LONDON First published 1959 Blandford Press Ltd 16 West Central St, London WC I SECOND IMPRESSION FEBRUARY 1960 The Author’s Royalties on this book are to be devoted to THE B.-P. CENTENARY FUND of the Boy Scouts International Bureau. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY TONBRIDGE PRINTERS LTD., PEACH HALL WORKS, TONBRIDGE, KENT Page 1 SCOUTING ROUND THE WORLD Downloaded from: “The Dump” at Scoutscan.com http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/ Editor’s Note: The reader is reminded that these texts have been written a long time ago. Consequently, they may use some terms or express sentiments which were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them at the beginning of the 21st century. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been preserved in their original form. If you find them offensive, we ask you to please delete this file from your system. This and other traditional Scouting texts may be downloaded from The Dump. CONTENTS Chapter Author’s Note Foreword 1 Fifty Years of Scouting 2 Early Personal Connections 3 How Scouting Spread 4 The First World War and its Aftermath 5 International Scout Centres – Gilwell Park, Kandersteg, Roland House 6 Scouting Grows Up 7 Coming-of-Age 8 The 1930’s – I 9 The I930’s – II 10 The Second World War 11 Linking Up Again 12 The International Bureau Goes on the Road 13 On to the ‘Jambores de la Paix’ 14 Absent Friends 15 Boy Scouts of America 16 1948-1950 – I 17 1948-1950 – II 18 The World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts 19 1951-1952 20 Latin America 21 The Far East and the Pacific 22 On to a New Phase and New Horizons 23 The Centenary and Golden Jubilee 24 Tradition Appendix Page 2 SCOUTING ROUND THE WORLD PHOTOGRAPHS (at end of book) B.-P. -

Mannelijkheid in Vlaamse Katholieke Scoutstroepen Tijdens Het Interbellum

Mannelijkheid in Vlaamse katholieke scoutstroepen tijdens het interbellum Pieter Henderix Promotor: Dr. Julie Carlier Masterproef voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het behalen van de graad Master in de Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2012 - 2013 Verklaring De auteur en de promotor(en) geven de toelating deze studie als geheel voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting de bron uitdrukkelijk te vermelden bij het aanhalen van gegevens uit deze studie. Het auteursrecht betreffende de gegevens vermeld in deze studie berust bij de promotor(en). Het auteursrecht beperkt zich tot de wijze waarop de auteur de problematiek van het onderwerp heeft benaderd en neergeschreven. De auteur respecteert daarbij het oorspronkelijke auteursrecht van de individueel geciteerde studies en eventueel bijhorende documentatie, zoals tabellen en figuren. De auteur en de promotor(en) zijn niet verantwoordelijk voor de behandelingen en eventuele doseringen die in deze studie geciteerd en beschreven zijn. Voorwoord Toen ik drie jaar geleden de beslissing nam om na mijn lerarenopleiding nog aan een schakelprogramma geschiedenis te beginnen, had ik eigenlijk geen flauw idee van wat mij te wachten stond. Ondertussen zijn we drie jaar verder en heb ik nog geen moment spijt van deze beslissing gehad. Persoonlijk vond ik de kennismaking met een academische opleiding een verrijkende ervaring. Niettemin begon ik toch steeds meer te voelen dat het tijd werd om het studentenleven achter mij te laten. Het schrijven van deze masterscriptie betekende voor mij dan ook in belangrijke mate het afsluiten van dit hoofdstuk.