Oesterheld's Iconic and Ironic Eternautas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desarrollo Del Campo De La Historieta Argentina: Entre La Dependencia Y

REVISTA ACADÉMICA DE LA FEDERACIÓN LATINOAMERICANA DE FACULTADES DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL ISSN: 1995 - 6630 Desarrollo del campo de la historieta argentina. Entre la dependencia y la autonomía Roberto von Sprecher Argentina [email protected] Roberto von Sprecher (Allen, Argentina, 1951). Doctor en Ciencias de la Información. Docente en la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba: Teorías Sociológicas I (Los clásicos), Sociología de la Historieta Realista, Teoría Social Contemporánea, Comunicaci ón y Trabajo Social. Director del Proyecto de Investigación Historietas realistas argentinas: estudios y estado del campo. Dirige la revista digital Estudios y Crítica de la Historieta Argentina (http://historietasargentinas.wordpress.com/). Libros: La Red Comunicacional, El Eternauta: la Sociedad como Imposible, en colaboración dos volúmenes sobre Teorías Sociológicas, etc Resumen: Analizamos el campo de la historieta realista argentina. Esto implica prestar atención a los factores estructurales, considerando que la historieta nace como parte de la industria cultural y dependiente del campo del mercado. Pero también damos importancia a las prácticas de construcción de los actores que forman parte del campo y que, en determinadas situaciones históricas, introducen modificaciones importantes y momentos de alta autonomía de lo económico. Destacamos el período de la segunda mitad los cincuentas con la aparición de la historieta de autor, la dictadura y la apertura democrática y, desde los noventa, la historieta independiente. Abstract: we analyze the field of the realistic Argentine comics. This implies to attend the structural factors, considering that comics were born as part of the cultural industry and subordinated to the market field. But also we give importance to the actors construction practices, as a part of the field, who, in certain historical situations, introduce important modifications and moments of high autonomy of the economic field. -

War Comics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

War comics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia War comics is a genre of comic books that gained popularity in English-speaking countries following War comics World War II. Contents 1 History 1.1 American war comics 1.2 End of the Silver Age 1.3 British war comics 2 Reprints 3 See also 4 References 5 Further reading 6 External links History American war comics Battlefield Action #67 (March 1981). Cover at by Pat Masulli and Rocco Mastroserio[1] Shortly after the birth of the modern comic book in the mid- to late 1930s, comics publishers began including stories of wartime adventures in the multi-genre This topic covers comics that fall under the military omnibus titles then popular as a format. Even prior to the fiction genre. U.S. involvement in World War II, comic books such as Publishers Quality Comics Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941) depicted DC Comics superheroes fighting Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Marvel Comics Golden Age publisher Quality Comics debuted its title Charlton Comics Blackhawk in 1944; the title was published more or less Publications Blackhawk continuously until the mid-1980s. Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos In the post-World War II era, comic books devoted Sgt. Rock solely to war stories began appearing, and gained G.I. Combat popularity the United States and Canada through the 1950s and even during the Vietnam War. The titles Commando Comics tended to concentrate on US military depictions, Creators Harvey Kurtzman generally in World War II, the Korean War or the Robert Kanigher Vietnam War. Most publishers produced anthologies; Joe Kubert industry giant DC Comics' war comics included such John Severin long-running titles as All-American Men of War, Our Russ Heath Army at War, Our Fighting Forces, and Star Spangled War Stories. -

Foreign Rights Guide Bologna 2019

ROCHETTE LE LOUP FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE BOLOGNA 2019 FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE BOLOGNE 2019 CONTENTS MASTERS OF COMICS GRAPHIC NOVELS BIOPICS • NON FICTION ADVENTURE • HISTORY SCIENCE FICTION • FANTASY HUMOUR LOUVRE ALL-AGES COMICS TINTIN ET LA LUNE – OBJECTIF LUNE ET ON A MARCHÉ SUR LA LUNE HERGÉ On the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Tintin and the 50th anniversary of the first step on the Moon, Tintin’s two iconic volumes combined in a double album. In Syldavia, Professor Calculus develops its motor atomic lunar rocket and is preparing to leave for the Moon. But mysterious incidents undermine this project: the test rocket is diverted, an attempt to steal plans occurs... Who is hiding behind this ? And will the rocket be able to take off ? We find our heroes aboard the first lunar rocket. But the flight is far from easy: besides the involuntary presence of Thompson and Thomson (which seriously limits the oxygen reserves), saboteurs are also on board. Will the rocket be back on Earth in time ? 240 x 320 • 128 pages • Colours • 19,90 € Publication : May 2019 90 YEARS OF ADVENTURES! Also Available MASTERS OF COMICS COMPLETE SERIES OF TINTIN HERGÉ MASTERS OF COMICS CORTO MALTESE – VOL. 14 EQUATORIA CANALES / PELLEJERO / PRATT Aft er a bestselling relaunch, the next adventure from Canales and Pellejero is here… It is 1911 and Corto Maltese is in Venice, accompanied by the National Geographic journalist Aïda Treat, who is hoping to write a profi le of him. Attempting to track down a mysterious mirror once owned by Prester John, Corto soon fi nds himself heading for Alexandria. -

The Secrets of Venice

Corto Maltese® & Hugo Pratt™ the secrets are © Cong SA. of venice... All rights reserved. the AdVENTURE! © Cong SA / Casterman THE SECRETS OF VENICE from “Fable of Venice” THE QUEST ON THIS ADVENTURE ADVENTURE Fable of Venice takes place in 1921 and is divided into four chapters. The background of the story Some places in Venice can reveal hidden CARDS is the rise of facism in Italy in the aftermath of the First World War. In this book, Hugo Pratt treasures… • 13 “character” cards shares some of his childhood memories and, as he often does, takes the reader into a true When the game is over, each “character” card • 3 “object” cards adventure novel. • 1 “advantage” card placed on a space with gold coins is worth that Under the watchful eyes of the god Abraxas, the masonic lodges and the facist militias, • 2 “Corto” cards much gold to the player controlling it. Corto Maltese, who came to Venice to solve a riddle given to him by his friend Baron Corvo, is • 1 “Rasputin” card tracking down the “Clavicle of Solomon”, a legendary emerald. In this story, full of suspens and unexpected events and which will eventually end in a dream, Corto will let us discover mysterious women, fallen aristocrats, “Blackshirts”, and magical places of Venice. In this example, the blue player gains 3 gold, green and yellow gain nothing. Bepi Faliero TEONE Louise Umberto Astronomer, astrologer and Brookszowyc Stevani mathematician, this master Better known as “the Beauty A young facist, member of of the occult sciences is also of Milano”, this friend of the Blackshirts of Venice. -

LOS ROSTROS DE LA VIOLENCIA. HISTORIETAS EN LA ARGENTINA EN PEDAZOS University of Texas at El Paso Con Estas Palabras, Ricardo P

Revista Iberoamericana, Vol. LXXVII, Núm. 234, Enero-Marzo 2011, 59-86 LOS ROSTROS DE LA VIOLENCIA. HISTORIETAS EN LA ARGENTINA EN PEDAZOS POR PEDRO PÉREZ DEL SOLAR University of Texas at El Paso La Argentina en pedazos. Una historia de la violencia argentina a través de la fi cción. ¿Qué historia es esa? La reconstrucción de una trama donde se pueden descifrar o imaginar los rastros que dejan en la literatura las relaciones de poder, las formas de la violencia. Marcas en el cuerpo y en el lenguaje, antes que nada, que permiten reconstruir la fi gura del país que alucinan los escritores. La Argentina en pedazos 8 Con estas palabras, Ricardo Piglia abre la primera entrega de la serie La Argentina en pedazos,1 publicada en el número inicial de la revista Fierro, en setiembre de 1984. Cada capítulo de esta serie consistirá de dos partes: un ensayo de Piglia y una historieta, ambos, cada uno a su manera, girando alrededor de un relato: cuento, novela, pieza teatral, letra de tango. No es casual que este replanteamiento de la historia argentina aparezca a sólo un año del fi n de la brutal dictadura militar. Los largos años de autoritarismo obligan a buscar nuevas lecturas de esta historia. El título de la serie, en este sentido, es revelador. “Pedazos” (fragmentos, ruinas) son el material con el que cuenta el crítico para su labor de reconstrucción. “Pedazos” también, hilados en narraciones, son las viñetas de las historietas. Los ensayos y las historietas de esta serie, ambos por igual, le seguirán la pista a esa violencia que recorre la literatura argentina. -

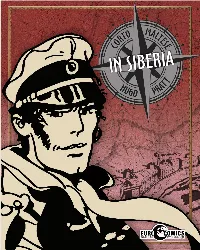

C O R T O M a L T E

HUGO PRATT HUGO Praise for HUGO PRATT and CORTO ALTESE h HARVEY AWARD WINNER and EISNER AWARD NOMINEE h Best U.S. Edition of International Material “An absolute treasure, containing outstanding work by an acknowledged master creator, one who has long been out of reach of comic book fans…. I recommend this to any true fan C of comic book storytelling. It’s that good.” O Project-Nerd R “Classic adventure comics for adults, enjoyable but with depth. Strongly recommended.” Library Journal T “Pratt’s tales are like coming home to an entire oeuvre of fables you’ve never known existed but O have always been waiting to read…I can guarantee that Corto Maltese will quickly become one of your most beloved protagonists.” M Alex Mangles, tor.com A “Classic adventure literature of the highest order.” L The New York Journal of Books T “The wordly magic of Hugo Pratt…an Italian masterpiece is coming to America.” Publishers Weekly E S “IDW’s collection brings Pratt’s iconic work to the U.S. without losing any of its heart and soul, and readers should quickly seize this opportunity to experience one of the medium’s great works.” E A.V. Club “These are the lines of a master, bringing you far-flung escapist adventures that take place in the early part of the 20th Century, a romantic world of rogues and scoundrels.” Dan Greenfield, 13th Dimension IN SIBERIA IN “There’s a reason that the EuroComics editions of Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese have been nominated for both the Eisner and Harvey Awards…. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña ISSN: 1659-4223 Universidad de Costa Rica Martín López, David; Jiménez Nievas, Antonio Hugo Pratt y la estética masónica: Corto Maltés, ¿el último romántico masón? Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 10, núm. 2, 2018, pp. 120-138 Universidad de Costa Rica DOI: 10.15517/rehmlac.v10i2.34965 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369562139008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, vol. 10, no. 2, diciembre 2018-mayo 2019/120-138 120 Hugo Pratt y la estética masónica: Corto Maltés, ¿el último romántico masón? Hugo Pratt and the Freemasonic Aesthetic: Corto Maltese, The Last Romantic Mason? David Martín López Universidad de Granada, España [email protected] Antonio Jiménez Nievas Universidad de Granada, España [email protected] Recepción: 23 de octubre de 2018/Aceptación: 18 de noviembre de 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.15517/rehmlac.v10i2.34965 Palabras clave Hugo Pratt; Corto Maltés; cómic; estética masónica; simbolismo; esoterismo; sociedades secretas. Keywords Hugo Pratt; Corto Maltese; comics; masonic aesthetics; symbolism; esoterism; secret societies. Resumen: Este artículo, con un marcado componente multidisciplinar, aborda la manera que ha tenido el cómic de plasmar el hecho masónico, principalmente centrándose en la obra paradigmática del artista francmasón italiano Hugo Pratt (1927-1995) y, especialmente, en su personaje Corto Maltés (1967-1992). -

Hugo Pratt Y Corto Maltés: Itinerarios Cruzados

HUGO PRATT Y CORTO MALTÉS: ITINERARIOS CRUZADOS Paco Linares Micó Seu Universitaria Ciutat d’Alacant Universitat d’Alacant 18.11.2015 - 28.01.2016 Hugo Pratt. © Cong S.A. Suiza CRÉDITS / CRÉDITOS COODINADOR I COMIssaRI / COORDINADOR Y COMIsaRIO: Paco Linares Micó PRODUCCIÓ / PRODUCCIÓN: Universitat d’Alacant DISSENY / DISEÑO: Bernabé Gómez Moreno XARXES SOCIALS / REDES SOCIALES: Manuel Pérez García ISBN: 978-84-943169-9-9 © Cong S.A. Suiza - www.cong-pratt.com © Corto Maltés publicado en español por Norma Editorial © Paco Linares Micó. Textos © Jordi Ojeda. Valores y tradiciones de la gente del mar en Corto Maltés HUGO PRATT Y CORTO MALTÉS: ITINERARIOS CRUZADOS Seu Universitaria Ciutat d’Alacant Universitat d’Alacant 18.11.2015 - 28.01.2016 HUGO PRATT, MESTRE Paco Linares Micó. Coordinador i comissari de la mostra Pocs autors han estat tan prop d’unir en un de sol aquests tres conceptes: autor, vida i obra. Aquest és el cas d’Hugo Pratt, a qui Umberto Eco va definir com un dels grans ar- tistes del segle XX, capaç de fer literatura amb el dibuix i dibuixar amb les paraules. Definint a grans trets l’obra de l’autor de Corto Maltés, es podria dir que va realitzar cò- mics que podria llegir el públic adolescent i ser apreciats al mateix temps per un professor universitari. I ho feia amb di- buixos d’una bellesa i tècnica narrativa exuberant, explicant histories cultes, però alhora apassionants i entretingudes. El 1967, abans de crear aquesta joia de la historieta mundial en què s’ha convertit Corto Maltés, Hugo Pratt ja comptava amb tot un món de viatges, aventures i filosofia.I tot aquest bagatge el va utilitzar per a donar vida al marí que es con- vertiria en el seu alter ego. -

Dossier De Presse Munoz / Breccia

Palais des Beaux-Arts | CHARLEROI | 30.nov.02 >>> 17.fev.03 3 Sommaire L’exposition Muñoz-/-Breccia : L'Argentine en Noir & Blanc confronte, à travers u n choix représentatif de près de 200 documents originaux, l'œuvre de d eux maîtres de la bande dessinée, dont l’importance est unanimement r econnue par la critique internationale. 4 | Argentine, terre de bandes dessinées 5 | Une exposition en ombres et lumières 6 | La bande dessinée comme œuvre de résistance 8 | Une esthétique du noir et blanc est une exposition organisée 10 | José Muñoz, une vie en exil par l'ASBL Charleroi Image de la Ville de Charleroi 12 | Entretien avec Muñoz et l'ASBL SAMARA 18 | Alberto Breccia, une vie en Argentine 20 | Breccia par Breccia Maître d’œuvre | A.S.B.L. Charleroi Imaginaire Jacques de Noore, président 22 | Bibliographie de Muñoz et Breccia Christian Renard, échevin de la culture Secrétariat général : Luc Daussaint 24 | En marge de l’exposition Coordination générale | Eric Verhoest Muñoz, Jeu de lumière Comité d’organisation | Christian Renard Erwin Dejasse Eric Verhoest Didier Pasamonik Irma Breccia José Muñoz Commissaire de l’exposition | Erwin Dejasse Scénographe & graphiste | Enzo Turco En couverture | Muñoz, portrait de Muñoz et Breccia Les dessins de Breccia sont © les héritiers de Breccia, les dessins de Muñoz sont © Muñoz et Sampayo 4 Argentine, terre de bandes dessinées 5 Une exposition en ombres et lumières Didier Pasamonik L’Argentine est un des grands pays produc- Mais l’école argentine n’en est pas moins teurs de la bande dessinée. Il est frappant riche : un premier groupe constitué autour de constater que ce territoire du bout du de Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia et Solano monde a accueilli sur ses terres des gens Lopez, puis José Muñoz, animé par Hector aussi différents que René Goscinny, le père Oesterheld, définit une grammaire graphique d’Astérix, qui y vécut toute son enfance, Hugo qui influencera jusqu’Art Spiegelman ou Pratt, le créateur de Corto Maltese, qui y créa Frédéric Bézian. -

El Corazón Delator De Alberto Breccia O Sobre Cómo Una Historieta Puede Subvertir La Violencia De La Mercancía. Pablo

TUMP! El Corazón Delator de Alberto Breccia o sobre cómo una historieta puede subvertir la violencia de la mercancía. Pablo Turnes RESUMEN A partir de 1974, Alberto Breccia comenzó una serie de adaptaciones historietísticas de algunos cuentos de Edgar Allan Poe. Para ello, hizo uso de recursos plásticos innovadores en el medio de la historieta entre los que se destacó la utilización de la puesta en página en base a la repetición exacerbada del esquema iterativo. De esta manera, Breccia dio cuenta de las posibilidades del lenguaje historietístico como específico de un medio particular, en diálogo con el relato cinematográfico y el literario, en lo que puede ser interpretado como una serie de trasvasamientos interactivos antes que una cualidad parasitaria de la historieta. Como ejemplo, analizaremos la primera de en la serie del ciclo de Poe: El Corazón Delator, y su construcción de una relación ideológica entre la forma de construcción del relato y una lectura de la violencia política argentina de mediados de la década de 1970. PALABRAS CLAVE: Género, Esquematismo, Memoria, Medios, Historieta. Profesor en Historia por la Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (UNMDP), Magíster en Historia del Arte por el Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales - Universidad Nacional de San Martín (IDAES/UNSAM), Becario Doctoral de CONICET, Doctorando en Ciencias Sociales en la Universidad de Buenos Aires (FSOC-UBA). 1 INTRODUCCIÓN A partir de 1974, Alberto Breccia (Montevideo, 1919 – Buenos Aires, 1993) comenzó una serie de adaptaciones historietísticas de algunos cuentos de Edgar Allan Poe1 (Boston, 1809 – Baltimore, 1849). Para ello, hizo uso de recursos plásticos innovadores en el medio de la historieta entre los que se destacó la utilización de la puesta en página en base a la repetición exacerbada del esquema iterativo. -

Dialogues Between Media

Dialogues between Media The Many Languages of Comparative Literature / La littérature comparée: multiples langues, multiples langages / Die vielen Sprachen der Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft Collected Papers of the 21st Congress of the ICLA Edited by Achim Hölter Volume 5 Dialogues between Media Edited by Paul Ferstl ISBN 978-3-11-064153-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-064205-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-064188-2 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110642056 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943602 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Paul Ferstl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com Cover: Andreas Homann, www.andreashomann.de Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Paul Ferstl Introduction: Dialogues between Media 1 1 Unsettled Narratives: Graphic Novel and Comics Studies in the Twenty-first Century Stefan Buchenberger, Kai Mikkonen The ICLA Research Committee on Comics Studies and Graphic Narrative: Introduction 13 Angelo Piepoli, Lisa DeTora, Umberto Rossi Unsettled Narratives: Graphic Novel and Comics -

NOTAS BIOGRÁFICAS SOBRE OESTERHELD Amaury Fernandes

NOTAS BIOGRÁFICAS SOBRE OESTERHELD Amaury Fernandes Escola de Comunicação, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil RESUMO Em nosso continente as histórias em quadrinhos com viés político devem muito da sua existência e importância à obra de Héctor Germán Oesterheld (1919 - desaparecido entre 1977 e 1978). O presente ensaio propõe a construção de um esboço biográfico, o estabelecimento de uma linha cronológica que alinhe o grau de engajamento político do roteirista à transformação dos aspectos ideológicos expostos em sua obra, em paralelo com o desdobramento da vida política da Argentina. Através da descrição e da análise de aspectos das narrativas das principais produções de Oesterheld, o objetivo central é evidenciar como seu envolvimento com movimentos políticos influencia na escolha de temas, cenários, discursos e no caráter dos personagens. Através de autores como Franco Ferraroti, Pierre Bourdieu e Leonor Arfuch buscamos construir uma breve biografia e, através do ferramental teórico da análise do discurso e da semiologia, descrever, detalhar e analisar as diversas séries de HQs, as biografias de personagens políticos da Argentina e demais trabalhos, para demonstrar o paralelismo existente entre a sua progressivamente maior participação na luta política da Argentina e a inclusão de aspectos profundamente ideológicos em seus trabalhos, vinculados aos grupos aos quais se filia. Assim podemos compreender parte de seu processo criativo, e construir um quadro com certa abrangência de sua obra, que circunscreva desde as suas primeiras produções na década de 1940 até as últimas, na segunda metade dos anos 1970, quando ocorrem seu sequestro e desaparecimento. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Héctor Germán Oesterheld; Biografia; Política na Argentina; Quadrinhos.