The Self-Reliant Defence of Australia: the History of an Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicals and Recurring Documents

PERIODICALS AND RECURRING DOCUMENTS May 2012 Legend A ANNUAL S-M SEMI-MONTHLY D DAILY BI-M BI-MONTHLY W WEEKLY Q QUARTERLY BI-W BI-WEEKLY TRI-A TRI-ANNUAL M MONTHLY IRR IRREGULAR S-A SEMI-ANNUAL A ACADEME. (BI-M) 1985-1989 ACADEMY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE. PROCEEDINGS. (IRR) 1960-1991 (MFILM 1975-1980) (MFICHE 1981-1982) ACQUISITION REVIEW QUARTERLY. (Q) 1994-2003 CONTINUED BY DEFENSE ACQUISITION REVIEW JOURNAL. AD ASTRA-TO THE STARS. (M) 1989-1992 ADA. (Q) 1991-1997 FORMERLY AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY. ADF: AFRICA DEFENSE FORUM. (Q) 2008- ADVANCE. (A) 1986-1994 ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. SEE S.A.M. ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. ADVISOR. (Q) 1974-1978 FORMERLY JOURNAL OF NAVY CIVILIAN MANPOWER MANAGEMENT. ADVOCATE. (BI-M) 1982-1984 - 1 - AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1977-1978 CONTINUED BY AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1979-1986 FORMERLY AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. AEROSPACE. (Q) 1963-1987 AEROSPACE AMERICA. (M) 1984-1998 FORMERLY ASTRONAUTICS & AERONAUTICS. AEROSPACE AND DEFENSE SCIENCE. (Q) 1990-1991 FORMERLY DEFENSE SCIENCE. AEROSPACE HISTORIAN. (Q) 1965-1988 FORMERLY AIRPOWER HISTORIAN. CONTINUED BY AIR POWER HISTORY. AEROSPACE INTERNATIONAL. (BI-M) 1967-1981 FORMERLY AIR FORCE SPACE DIGEST INTERNATIONAL. AEROSPACE MEDICINE. (M) 1973-1974 CONTINUED BY AVIATION SPACE AND EVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE. AEROSPACE POWER JOURNAL. (Q) 1999-2002 FORMERLY AIRPOWER JOURNAL. CONTINUED BY AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL. AEROSPACE SAFETY. (M) 1976-1980 AFRICA REPORT. (BI-M) 1967-1995 (MFICHE 1979-1994) AFRICA TODAY. (Q) 1963-1990; (MFICHE 1979-1990) 1999-2007 AFRICAN SECURITY. (Q) 2010- AGENDA. (M) 1978-1982 AGORA. -

Australia's Strategic Culture and Constraints in Defence

International Studies Association – Annual Convention 2013 Australia’s Strategic Culture and Constraints in Defence and National Security Policymaking Alex Burns, PhD Candidate, Monash University ([email protected]) Ben Eltham, PhD Candidate, University of Western Sydney ([email protected]) Abstract Scholars have advanced different conceptualisations of Australia’s strategic culture. Collectively, this work contends Australia is a ‘middle power’ nation with a realist defence policy, elite discourse, entrenched military services, and a regional focus. This paper contends that Australia’s strategic culture has unresolved tensions due to the lack of an overarching national security framework, and policymaking constraints at two interlocking levels: cultural worldviews and institutional design that affects strategy formulation and resource allocation. The cultural constraints include confusion over national security policy, the prevalence of neorealist strategic studies, the Defence Department’s dominant role in formulating strategic doctrines, and problematic experiences with Asian ‘regional engagement’ and the Pacific Islands. The institutional constraints include resourcing, inter-departmental coordination, a narrow approach to government white papers, and barriers to long-term strategic planning. In this paper, we examine possibilities for continuity and change, including the Gillard Government’s Asian Century White Paper, National Security Strategy and the forthcoming 2013 Defence White Paper. Introduction Digging Up Silos in Australia’s National Security Community On 23rd January 2013, the Gillard Government released Australia’s first National Security Strategy (NSS): Strong and Secure: A Strategy for Australia’s National Security.1 Amongst the NSS initiatives was a new Australian Cyber Security Centre that would coordinate Australian Federal Government expertise to combat cyber-attacks and cybercrime, provide cybersecurity and to strengthen the National Broadband Network’s rollout. -

Indigenous Australians Brochure

SEE YOURSELF IN A REWARDING ROLE CHOOSE A JOB IN A DIVERSE AND SUPPORTIVE WORKPLACE A CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR COUNTRY’S DEFENCE THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE (ADF) IS AN EMPLOYER OF CHOICE FOR HUNDREDS OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS. Help maintain a proud tradition of service by joining the thousands of Indigenous men and women who for over 100 years, have contributed to the protection of our country and its interests as members of the ADF. In the Navy, Army or Air Force, you’ll work alongside Indigenous Australians from across the ranks, enjoying opportunities rarely found in civilian employment. As you serve your country and community, your abilities will be nurtured and given focus. You’ll receive world-class training and be given the opportunity to earn qualifications that will give you the skills, knowledge and experience to reach your full potential in a fulfilling role. 01 FEATURED 04 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE 08 RECEIVE WORLD-CLASS TRAINING INSIDE AND EDUCATION 09 CHOOSE YOUR IDEAL ROLE 10 ENTER THE WAY YOU WANT TO 14 ACHIEVE YOUR POTENTIAL 16 INDIGENOUS PRE-RECRUIT PROGRAM 18 NAVY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 20 ARMY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 22 AIR FORCE INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES 26 ACCESS FLEXIBLE ENTRY PATHWAYS 28 HOW TO JOIN 32 CONTACT US 02 03 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE REWARDING, WELL-PAID WORK IS JUST THE START. AS A FULL-TIME MEMBER OF THE ADF YOU’LL ENJOY: A friendly and supportive team environment that embraces cultural, social and workforce diversity A competitive salary and superannuation Equal pay regardless -

History As Policy

The Strategic and Defence Studies Centre’s 40th anniversary seminar series The Strategic and Defence Studies Centre is a research centre within the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies in the College of Asia and the Pacific at The Australian National University in Canberra, the country's capital. In the second half of 2006, the Centre marked the fortieth anniversary of its founding in 1966 with a series of three seminars (and a dinner) under the theme of History as Policy. Held on 8 August 2006 at the Boat House by the Lake in Canberra (<http://www.boathousebythelake.com.au/>), the dinner was addressed by Professor Wang Gungwu, who gave a masterly sketch of the strategic implications of the rise of China, drawing on his deep knowledge of China's history. Guests included the current Chief of the Defence Force, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, the then Secretary of Defence, Ric Smith, and other key figures from the policy world, the intelligence community, and the media. Also in attendance were colleagues from The Australian National University, including the Convenor of the College of Asia and the Pacific, Professor Robin Jeffrey. Boeing Holdings Australia Ltd continued a long tradition of support to the Centre by generously sponsoring the seminar series and the dinner (which was attended by Paul Gargette, its Vice President of Operations and Business Integration). The three anniversary seminars were held on 15 August, 14 September and 10 October 2007 at University House on the grounds of The Australian National University (<http://www.anu.edu.au/unihouse/>). Speakers at the first seminar on Global Strategic Issues were Robert O'Neill (`Changing concepts of the nature of security and the role of armed force'), Hugh White (`Predictions and policy'), Coral Bell (`The evolution of the international system'), and Ron Huisken (`Whither the United States?'). -

How Did Indigenous Australians Contribute to the Defence Of

How did Indigenous Australians help in the Defence of Australia in World War 2? WHAT DOES THIS TELL US ABOUT CITIZENSHIP? We do not know much about Indigenous service in the Australian armed forces. However, we are now starting to discover more as interest in Australia’s Indigenous history grows. In this unit we have gathered together information and evidence about Indigenous Australians’ service in World War 2, and in particular their involvement in the northern Defence of Australia. By looking at this information and evidence you will be able to explore the two great themes we have been presenting in the Defence 2020 program this year: Citizenship, and Plaque at Rocky Creek, Role Models. Atherton Tablelands, Queensland Your task Indigenous involvement in the Defence of Australia in World War 2 Your task is to look at the sources presented on the next pages, and to use them to answer Who was involved? the sorts of key questions that are part of any What did they do? historical inquiry. You can use a table like this: When did they do it? Conclusion Where did they do it? When you have completed your summary table Why did they do it? from all the sources decide on your answers to these questions: What were the impacts of the involvement? Did Indigenous Australians show good What were the consequences of the involvement? citizenship during the war? Did Indigenous people provide good role models that we could follow today? Further Reading Did non-Indigenous Australians show good citizenship towards Indigenous Australians? Ball, Desmond. Aborigines in the defence of Australia. -

Australian Defence Force's Approach for the Protection of Civilian (POC): Perspectives of Guidelines, Training and WPS Introd

Australian Defence Force’s Approach for the Protection of Civilian (POC): Perspectives of Guidelines, Training and WPS CDR Takashi Kawashima, Japan Peacekeeping Training and Research Center *This document is the translation of research paper in Japanese produced as part of the outreach effort of Japan Peacekeeping Training and Research Center (JPC). Contents Introduction: The Protection of Civilian as the Operational Challenge of Military Force ............... 1 1. The Overview and the Background of Australia’s efforts for POC ............................................. 4 (1) Military Aspect: ADF’s Operational Experiences of POC in East Timor ............................... 4 (2) Policy Aspect-1: Contribution to the POC in International Community ................................. 8 (3) Policy Aspect-2: Promotion of POC in the context of Women, Peace and Security (WPS) 9 2. Specific measures of ADF for promoting the POC ................................................................... 14 (1) Defining Australia’s unified concept of POC: development of the POC Guidelines ........... 14 (2) Development of POC Training Modules .............................................................................. 18 3. POC as the essential element of WPS ..................................................................................... 21 (1) Female Engagement Team (FET) and Gender Advisor (GA) ............................................ 22 (2) Integration of WPS into multilateral joint exercise: Talisman Sabre .................................. -

ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE in the AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE: TOWARDS a UNIQUE SOLUTION Brigadier Peter J. Dunn, AM Master of Defence S

ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE IN THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE: TOWARDS A UNIQUE SOLUTION Brigadier Peter J. Dunn, AM Master of Defence Studies Sub-Thesis University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1994 CONTENTS PARTS 1 PRINCIPAL CHANGES IN AUSTRALIA'S MILITARY COMMAND STRUCTURE SINCE THE 1950s 1 2 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE THEORY AND REVIEWS OF THE ADF 16 3 A CHANGING ORGANISATIONAL ENVIRONMENT FOR THE ADF- THE NEED TO FOCUS ON "CORE BUSINESS" 27 4 ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE FOR MORE EFFECTIVE ADF OPERATIONS 45 5 CONCLUSIONS 68 BIBLIOGR.\PHY 74 FIGURES 1 LOCBI IN THE PRE-BAKER STUDY ADF 32 2 LOCBI IN THE POST- BAKER STUDY ADF 33 3 OPERATIONAL FLEXIBILITY IN THE ADF STRUCTURE 42 4 MODEL ONE ADF ORGANISATION 53 5 MODEL TWO ADF ORGANISATION 57 6 MODEL THREE ADF ORGANISATION 66 Ill ABSTR.4CT The Australian Defence organisation has been the subject of almost constant review since the 1950s. The first of these major reviews, the Morshead Review was initiated in 1957. This review coincided with the growing realisation that Australia had to become more self reliant in defence matters. The experience of World War Two had shown that total reliance on "great and powerful friends" was a dangerous practice and self reliance dictated that Australia's military forces would have to act together in a joint environment. Australia's system of military command had to be capable of producing effective policies and planning guidance to met the new demands of independent joint operations. Successive reviews aimed at moving the Australian Defence Forces toward a more joint organisation have resulted in major changes to the higher defence machinery. -

The Potential Benefits to the Australian Defence Force Educational Curricula of the Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge Systems

The Potential Benefits to the Australian Defence Force Educational Curricula of the Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge Systems Debbie Fiona Hohaia, Master Professional Studies (Aboriginal Studies) Bachelor Education, Diploma Teaching, Diploma Management, Diploma Human Resources, Diploma of Government This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Indigenous Knowledges and Public Policy, Charles Darwin University 18 January 2016 Declaration I hereby declare that the work herein, now submitted as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Charles Darwin University, is the result of my own investigations and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Australian Defence Force, the New Zealand Defence Force or any extant policy. All reference to ideas and the work of other researchers have been specifically acknowledged. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis has not already been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not being submitted in candidature for any other degree. I acknowledge that the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council and the Australian Vice Chancellors Committee, March 2007) has been adhered to. The work in this thesis was undertaken between the dates of December 2012 to December 2014 and in no way reflects the advancements that have been made by various elements of the Australian Defence Force and the cultural diversity initiatives, which have been embedded within the last 18 months. Full name: Debbie Fiona Hohaia Signed: Date: 18 January 2016 Page I Acknowledgements There are many people who have contributed and participated in this research. -

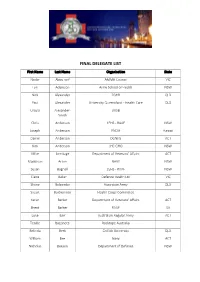

Final Delegate List

FINAL DELEGATE LIST First Name Last Name Organisation State Nader Abou-seif AMMA Council VIC Lyn Adamson Army School of Health NSW Nick Alexander 2GHB QLD Paul Alexander University Queensland - Health Care QLD Ursula Alexander- 3HSB Smith Chris Anderson 1EHS - RAAF NSW Joseph Anderson PACAF Hawaii Daniel Anderson DGNHS ACT Kim Anderson JHC GHO NSW Mike Armitage Department of Veterans' Affairs ACT Maddison Arton NAVY NSW Susan Bagnall 2EHS - RAAF NSW Claire Baker Defence Health Ltd VIC Shane Balcombe Australian Army QLD Stuart Baldwinson Health Corps Committee Karen Barker Department of Veterans' Affairs ACT Brent Barker RAAF SA Luke Barr Australian Regular Army ACT Tenille Bazzinotti Rocktape Australia Belinda Beck Griffith University QLD William Bee Navy ACT Nicholas Beeson Department of Defence NSW Bevan Begeda Philips QLD Daniel Belanszky Army QLD Alan Bell Aware Medical NSW Helen Benassi Department of Defence ACT Clare Bennett New Zealand Defence Force New Zealand Victoria Bensley 3HSB Cecilia Berryman Directorate Navy Health Julie Blackburn Defence Health Foundation ACT Julie Blogg Stirling Health Centre WA Amy Bowden HOCU - RAAF QLD Mark Brazier Department of Defence ACT Jordan Breed RAAF VIC Mackay Brendan Australian Regular Army NSW Leonard Brennan Joint Health Command ACT Di Bridger RAAF NSW Matt Briffa Zoll NSW Jamie Briskey Australian Army Adrian Brooks OPSWO Army School of Health Adam Bryant University of Melbourne VIC Emma Bucknell JHC GHO ACT David Bullock Army QLD Jessica Burton Department of Defence QLD Toni Bushby Australian -

Australia and US-China Relations

43 Australia and U.S.-China Relations: Bandwagoned and Unbalancing Malcolm Cook 44 | Joint U.S.-Korea Academic Studies “We know Communist China is there; we want to live with it, and we are willing to explore new ways of doing so; but we are not prepared to fall flat on our face before it.” Foreign Minister Paul Hasluck, August 18, 19661 Since Kevin Rudd and the Australian Labor Party ended Prime Minister John Howard’s 11 1/2 years in office in late 2007, each new government in Canberra has faced a very similar and rather narrow foreign policy fixation. Australia’s relations with China, and Australian policies or pronouncements that may affect China, have become the main focus of foreign policy commentary both inside and outside the country. Increasingly, Australia’s own defense and foreign policy pronouncements and long-standing and deep relations with the United States and Japan are being reinterpreted through this China lens. This mostly critical commentary has tried to divine new directions in Australian foreign and security policy and reasons why these perceived new directions are harmful to Australia’s relations with China. From their very first baby steps, the Abbott administration and Prime Minister Tony Abbott himself have been subject to this increasingly singular China-centered focus and its set of questionable underlying assumptions. The Australian case, as this book, is both animated by and significantly questions two systemic assumptions about the emergence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as Asia’s leading economic power and U.S.-China relations. The first systemic assumption at the core of the realist tradition of thought is that the rise of a new power destabilizes the affected security order and consequently states in that order will change policies to respond to this rise and associated destabilization. -

A New Flank: Fresh Perspectives for the Next Defence White Paper April 2013

THE CENTRE OF GRAVITY SERIES A NEW FLANK: FRESH PERSPECTIVES FOR THE NEXT DEFENCE WHITE PAPER April 2013 Strategic & Defence Studies Centre ANU College of Asia & the Pacific The Australian National University ABOUT THE SERIES The Centre of Gravity series is the flagship publication of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre (SDSC) based at The Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific. The series aspires to provide high quality analysis and to generate debate on strategic policy issues of direct relevance to Australia. Centre of Gravity papers are 1,500-2,000 words in length and are written for a policy audience. Consistent with this, each Centre of Gravity paper includes at least one policy recommendation. Papers are commissioned by SDSC and appearance in the series is by invitation only. SDSC commissions up to 10 papers in any given year. Further information is available from the Centre of Gravity series editor Dr Andrew Carr ([email protected]). Centre of Gravity series paper #6 Cover photo of Signalman Kit Drury on tower guard duty as part of Operation Catalyst, Iraq. Cover photo courtesy of the Australian Department of Defence. © 2013 ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. All rights reserved. The Australian National University does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University, its staff, or its trustees. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the ANU Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. -

ANU Strategic & Defence Studies Centre's Golden Anniversary

New Directions in Strategic Thinking 2.0 ANU STRATEGIC & DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE’S GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS New Directions in Strategic Thinking 2.0 ANU STRATEGIC & DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE’S GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS EDITED BY DR RUSSELL W. GLENN Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760462222 ISBN (online): 9781760462239 WorldCat (print): 1042559418 WorldCat (online): 1042559355 DOI: 10.22459/NDST.07.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents Foreword . vii Preface . xi Contributors . xiii Acronyms and abbreviations . xxiii 1 . Introduction . 1 Russell W . Glenn 2 . The decline of the classical model of military strategy . 9 Lawrence Freedman 3 . Economics and security . 23 Amy King 4 . A bias for action? The military as an element of national power . 37 John J . Frewen 5 . The prospects for a Great Power ‘grand bargain’ in East Asia . 51 Evelyn Goh 6 . Old wine in new bottles? The continued relevance of Cold War strategic concepts . 63 Robert Ayson 7 . Beyond ‘hangovers’: The new parameters of post–Cold War nuclear strategy . 77 Nicola Leveringhaus 8 . The return of geography . 91 Paul Dibb 9 . Strategic studies in practice: An Australian perspective . 105 Hugh White 10 . Strategic studies in practice: A South-East Asian perspective .