ORGANISATIONAL CHANGE in the AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE: TOWARDS a UNIQUE SOLUTION Brigadier Peter J. Dunn, AM Master of Defence S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3: Australian Force Structure, Interoperability and Intelligence

3 Australian force structure, interoperability and intelligence Introduction 3.1 The Australian Defence Force (ADF) remains primarily structured for operations in defence of Australia1, yet it is increasingly involved in coalition operations with US forces, supporting Australia’s wider interests and objectives beyond our immediate neighbourhood. An ongoing challenge for the ADF is to determine the most effective way it can contribute both to potential operations in Defence of Australia, and the increasingly more demanding operations beyond our immediate neighbourhood. 3.2 The moderate levels of conventional threat in Australia’s immediate region, linked with the low likelihood of a conventional attack on Australia, compared to the high threats faced by the ADF when deployed to locations like Iraq and Afghanistan raises questions about the suitability of Australia’s force structure. Evidence to the inquiry is divided over whether adjustments to force structure, as a result of coalition operations a long way from Australia, are justified. 3.3 A number of force structure determinants are emerging from Australia’s recent involvement in coalition operations. The key determinant for conducting coalition operations remains, however, the ability to be interoperable with our allies in a range of key areas. The importance of interoperability to ADF operations will be examined and the key issues raised in evidence will be discussed. 1 Australian Government, Defence 2000 – Our Future Defence Force, p. XI. 24 AUSTRALIA’S DEFENCE RELATIONS WITH THE US 3.4 The final section of the chapter examines the significance of intelligence sharing between Australia and the US. The discussion will explore the key benefits and disadvantages of our intelligence sharing arrangements. -

Periodicals and Recurring Documents

PERIODICALS AND RECURRING DOCUMENTS May 2012 Legend A ANNUAL S-M SEMI-MONTHLY D DAILY BI-M BI-MONTHLY W WEEKLY Q QUARTERLY BI-W BI-WEEKLY TRI-A TRI-ANNUAL M MONTHLY IRR IRREGULAR S-A SEMI-ANNUAL A ACADEME. (BI-M) 1985-1989 ACADEMY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE. PROCEEDINGS. (IRR) 1960-1991 (MFILM 1975-1980) (MFICHE 1981-1982) ACQUISITION REVIEW QUARTERLY. (Q) 1994-2003 CONTINUED BY DEFENSE ACQUISITION REVIEW JOURNAL. AD ASTRA-TO THE STARS. (M) 1989-1992 ADA. (Q) 1991-1997 FORMERLY AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY. ADF: AFRICA DEFENSE FORUM. (Q) 2008- ADVANCE. (A) 1986-1994 ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. SEE S.A.M. ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. ADVISOR. (Q) 1974-1978 FORMERLY JOURNAL OF NAVY CIVILIAN MANPOWER MANAGEMENT. ADVOCATE. (BI-M) 1982-1984 - 1 - AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1977-1978 CONTINUED BY AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1979-1986 FORMERLY AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. AEROSPACE. (Q) 1963-1987 AEROSPACE AMERICA. (M) 1984-1998 FORMERLY ASTRONAUTICS & AERONAUTICS. AEROSPACE AND DEFENSE SCIENCE. (Q) 1990-1991 FORMERLY DEFENSE SCIENCE. AEROSPACE HISTORIAN. (Q) 1965-1988 FORMERLY AIRPOWER HISTORIAN. CONTINUED BY AIR POWER HISTORY. AEROSPACE INTERNATIONAL. (BI-M) 1967-1981 FORMERLY AIR FORCE SPACE DIGEST INTERNATIONAL. AEROSPACE MEDICINE. (M) 1973-1974 CONTINUED BY AVIATION SPACE AND EVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE. AEROSPACE POWER JOURNAL. (Q) 1999-2002 FORMERLY AIRPOWER JOURNAL. CONTINUED BY AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL. AEROSPACE SAFETY. (M) 1976-1980 AFRICA REPORT. (BI-M) 1967-1995 (MFICHE 1979-1994) AFRICA TODAY. (Q) 1963-1990; (MFICHE 1979-1990) 1999-2007 AFRICAN SECURITY. (Q) 2010- AGENDA. (M) 1978-1982 AGORA. -

Indigenous Australians Brochure

SEE YOURSELF IN A REWARDING ROLE CHOOSE A JOB IN A DIVERSE AND SUPPORTIVE WORKPLACE A CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR COUNTRY’S DEFENCE THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE (ADF) IS AN EMPLOYER OF CHOICE FOR HUNDREDS OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS. Help maintain a proud tradition of service by joining the thousands of Indigenous men and women who for over 100 years, have contributed to the protection of our country and its interests as members of the ADF. In the Navy, Army or Air Force, you’ll work alongside Indigenous Australians from across the ranks, enjoying opportunities rarely found in civilian employment. As you serve your country and community, your abilities will be nurtured and given focus. You’ll receive world-class training and be given the opportunity to earn qualifications that will give you the skills, knowledge and experience to reach your full potential in a fulfilling role. 01 FEATURED 04 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE 08 RECEIVE WORLD-CLASS TRAINING INSIDE AND EDUCATION 09 CHOOSE YOUR IDEAL ROLE 10 ENTER THE WAY YOU WANT TO 14 ACHIEVE YOUR POTENTIAL 16 INDIGENOUS PRE-RECRUIT PROGRAM 18 NAVY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 20 ARMY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 22 AIR FORCE INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES 26 ACCESS FLEXIBLE ENTRY PATHWAYS 28 HOW TO JOIN 32 CONTACT US 02 03 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE REWARDING, WELL-PAID WORK IS JUST THE START. AS A FULL-TIME MEMBER OF THE ADF YOU’LL ENJOY: A friendly and supportive team environment that embraces cultural, social and workforce diversity A competitive salary and superannuation Equal pay regardless -

Person Name - Prefix a Table of Salutations That May Precede an Individual’S Name to Identify Social Status

Person Name - Prefix A table of salutations that may precede an individual’s name to identify social status. Accurate and uniform information is key to exchanging data. The table below is the recommended format for an individuals name prefix. Note: Military abbreviations are provided in Non Department of National Defence writing format as per "The Canadian Style, A Guide to Writing and Editing" published in 1997. Prefix Abbreviation Second Lieutenant 2nd Lieut. Acting Sub-Lieutenant Acting Sub-Lieutenant Able Seaman A.B. Abbot Ab. Archbishop Abp. Admiral Admiral Brigadier-General Brig.-Gen Brother Bro. Base Chief Petty Officer BsCPO Captain Capt. Commander Cmdr. Chief Chief Commodore Commodore Colonel Col. Constable Const. Corporal Cpl. Chief Petty Officer 1st class Chief Petty Officer, 1st class Chief Petty Officer 2nd class Chief Petty Officer, 2nd class Constable Cst. Chief Warrant Officer Chief Warrant Officer Doctor Dr. Bishop (Episcopus) Episc Your Excellency Exc. Father Fr. General Gen. Her Worship Her Worship Her Excellency HerEx His Worship His Worship His Excellency HisEx Honourable Hon. Lieutenant-Commander Lt.-Cmdr Lieutenant-Colonel Lt.-Col Lieutenant-General Lt.-Gen Leading Seaman L.S. Lieutenant Lieut. Monsieur M. Person Name - Prefix Prefix Abbreviation Master Ma. Madam Madam Major Maj. Mayor Mayor Master Corporal Master Corporal Major-General Maj.-Gen Miss Miss Mademoiselle Mlle. Madame Mme. Mister Mr. Mistress Mrs. Ms Ms. Master Seaman M.S. Monsignor Msgr. Monsieur Mssr. Master Mstr Master Warrant Officer Master Warrant Officer Naval Cadet Naval Cadet Officer Cadet Officer Cadet Ordinary Seaman O.S. Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 2nd class Petty Officer, 2nd class Professor Prof. -

Initial Layout 31 KH.Indd

hidden assets contents 4 evolution of the submarine 8 submarines in australia 10 collins class project 14 collins class submarines 16 submarine construction 18 role of submarines 20 relative complexity of submarines 22 submarines of the future 3 While it is widely considered that William Borne designed the first submarine in 1578, it was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) who initially developed the idea of a military vessel evolution that could submerge under water to attack enemy ships. However, it wasn’t until 1776 that the first submarine to make an attack on an enemy ship was built. Named the Turtle, it was designed by David Bushnell and was built with the intention of breaking the British of the submarine naval blockade in New York Harbor during the American Revolution. Operated by Sergeant Ezra Lee, the Turtle made an unsuccessful attack on a British ship on 7 September 1776. Several more submarines were attempted over the years, but it wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th century that modern day submarine warfare was born. At the start of World War I, submarines were still in their infancy. Considered to be ‘unethical’ and not fitting into the conventional rules of war, few foresaw the watershed in naval warfare that submarines were to bring about. Once their true capabilities were realised, submarines had a substantial impact on World War I: sinking ships, laying mines, blockading ports and providing escorts to trans-Atlantic convoys. During World War II, submarine technology advanced significantly. The Germans, who were operating U-Boats in the Atlantic Ocean, developed the ‘snorkel’ (allowing the boat to recharge its batteries while staying submerged). -

Management of Operations at Pine Gap

The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability Management of Operations at Pine Gap Desmond Ball, Bill Robinson and Richard Tanter Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability Special Report 24 November 2015 Summary The management of operations at the Pine Gap facility has become increasingly complex as the functions of the station have expanded, the number of agencies involved has grown, and the demands of a wider range of ‘users’ or ‘customers’ for the provision of ‘actionable intelligence’ in near real-time have increased markedly. Operations at Pine Gap are now completely integrated, in terms of American and Australian, civilian and military, and contractor personnel working together in the Operations Room; the organisational structure for managing operations, which embodies concerted collaboration of multiple US agencies, including the National Reconnaissance Office, Central Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, Service Cryptologic Agencies and the National Geospatial- Intelligence Agency (NGA); and functionally with respect to signals intelligence (SIGINT) collected by the geosynchronous SIGINT satellites controlled by Pine Gap, communications intelligence collected by foreign satellite/communications satellite (FORNSAT/COMSAT) interception systems at Pine Gap, and imagery and geospatial intelligence produced by the NGA, as well as missile launch detection and tracking data. Conceptualising the extraordinary growth and expansion of operations at Pine Gap is not easy – by the nature of the facility. Externally, it is evident in the increase in size of the two main operations buildings within the high security compound – areas quite distinct from the separate part of the facility that deals with administration matters. The total area of floor space in the Operations Buildings has increased five-fold since 1970 to more than 20,000 m2. -

Terms of Reference a the Reasons Why Australian Veterans Are Committing Suicide at Such High Rates

1 SENATE FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND TRADE COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO SUICIDE BY VETERANS AND EX-SERVICE PERSONNEL Submitted by: Name withheld Terms of reference A The Reasons why Australian Veterans are Committing Suicide at Such High Rates. This term of reference acknowledges that Australian veterans are committing suicide at high rates, but provides no figures on the actual numbers of suicides. This is because neither the ADF nor DVA record actual suicides of veterans. This is a matter of serious concern for veterans, their families and in fact the Australian nation. If the US can record accurate data on suicides of its veterans, then so too can Australia. Perhaps the ADF and DVA have taken a conscious decision not to record these figures. I feel the following excerpts from an article by David Ellery in the Sydney Morning Herald, 7 June 2015, titled Alarming' rise in suicide deaths by former military personnel, are very relevant to this Inquiry, Refer: http://www.smh.com.au/national/alarming-rise-in-suicide-deaths-by-former-military- personnel-20150605-ghhfut.html Despite Defence's multibillion-dollar resources, Vice Chief of Defence Force, Vice Admiral Ray Griggs said: "What is the suicide rate amongst the ex-serving community? We just don't know ... People get very energetic and say `you should know'. Well, we'd love to know." The ADF was scrambling to plug the information black hole by working with a wide range of stakeholders, including a grassroots suicide register whose founder said his job was "speaking for the dead". Admiral Griggs, said “he did not believe claims held up that as many as 200 Afghan war veterans had committed suicide”. -

Albert J. Baciocco, Jr. Vice Admiral, US Navy (Retired)

Albert J. Baciocco, Jr. Vice Admiral, U. S. Navy (Retired) - - - - Vice Admiral Baciocco was born in San Francisco, California, on March 4, 1931. He graduated from Lowell High School and was accepted into Stanford University prior to entering the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, in June 1949. He graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1953 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Engineering, and completed graduate level studies in the field of nuclear engineering in 1958 as part of his training for the naval nuclear propulsion program. Admiral Baciocco served initially in the heavy cruiser USS SAINT PAUL (CA73) during the final days of the Korean War, and then in the diesel submarine USS WAHOO (SS565) until April of 1957 when he became one of the early officer selectees for the Navy's nuclear submarine program. After completion of his nuclear training, he served in the commissioning crews of three nuclear attack submarines: USS SCORPION (SSN589), as Main Propulsion Assistant (1959-1961); USS BARB (SSN596), as Engineer Officer (1961-1962), then as Executive Officer (1963- 1965); and USS GATO (SSN615), as Commanding Officer (1965-1969). Subsequent at-sea assignments, all headquartered in Charleston, South Carolina, included COMMANDER SUBMARINE DIVISION FORTY-TWO (1969-1971), where he was responsible for the operational training readiness of six SSNs; COMMANDER SUBMARINE SQUADRON FOUR (1974-1976), where he was responsible for the operational and material readiness of fifteen SSNs; and COMMANDER SUBMARINE GROUP SIX (1981-1983), where, during the height of the Cold War, he was accountable for the overall readiness of a major portion of the Atlantic Fleet submarine force, including forty SSNs, 20 SSBNs, and various other submarine force commands totaling approximately 20,000 military personnel, among which numbered some forty strategic submarine crews. -

Australia's Joint Approach Past, Present and Future

Australia’s Joint Approach Past, Present and Future Joint Studies Paper Series No. 1 Tim McKenna & Tim McKay This page is intentionally blank AUSTRALIA’S JOINT APPROACH PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE by Tim McKenna & Tim McKay Foreword Welcome to Defence’s Joint Studies Paper Series, launched as we continue the strategic shift towards the Australian Defence Force (ADF) being a more integrated joint force. This series aims to broaden and deepen our ideas about joint and focus our vision through a single warfighting lens. The ADF’s activities have not existed this coherently in the joint context for quite some time. With the innovative ideas presented in these pages and those of future submissions, we are aiming to provoke debate on strategy-led and evidence-based ideas for the potent, agile and capable joint future force. The simple nature of ‘joint’—‘shared, held, or made by two or more together’—means it cannot occur in splendid isolation. We need to draw on experts and information sources both from within the Department of Defence and beyond; from Core Agencies, academia, industry and our allied partners. You are the experts within your domains; we respect that, and need your engagement to tell a full story. We encourage the submission of detailed research papers examining the elements of Australian Defence ‘jointness’—officially defined as ‘activities, operations and organisations in which elements of at least two Services participate’, and which is reliant upon support from the Australian Public Service, industry and other government agencies. This series expands on the success of the three Services, which have each published research papers that have enhanced ADF understanding and practice in the sea, land, air and space domains. -

Understanding the First AIF: a Brief Guide

Last updated August 2021 Understanding the First AIF: A Brief Guide This document has been prepared as part of the Royal Australian Historical Society’s Researching Soldiers in Your Local Community project. It is intended as a brief guide to understanding the history and structure of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I, so you may place your local soldier’s service in a more detailed context. A glossary of military terminology and abbreviations is provided on page 25 of the downloadable research guide for this project. The First AIF The Australian Imperial Force was first raised in 1914 in response to the outbreak of global war. By the end of the conflict, it was one of only three belligerent armies that remained an all-volunteer force, alongside India and South Africa. Though known at the time as the AIF, today it is referred to as the First AIF—just like the Great War is now known as World War I. The first enlistees with the AIF made up one and a half divisions. They were sent to Egypt for training and combined with the New Zealand brigades to form the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). It was these men who served on Gallipoli, between April and December 1915. The 3rd Division of the AIF was raised in February 1916 and quickly moved to Britain for training. After the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula, 4th and 5th Divisions were created from the existing 1st and 2nd, before being sent to France in 1916. -

How Did Indigenous Australians Contribute to the Defence Of

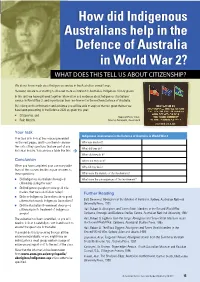

How did Indigenous Australians help in the Defence of Australia in World War 2? WHAT DOES THIS TELL US ABOUT CITIZENSHIP? We do not know much about Indigenous service in the Australian armed forces. However, we are now starting to discover more as interest in Australia’s Indigenous history grows. In this unit we have gathered together information and evidence about Indigenous Australians’ service in World War 2, and in particular their involvement in the northern Defence of Australia. By looking at this information and evidence you will be able to explore the two great themes we have been presenting in the Defence 2020 program this year: Citizenship, and Plaque at Rocky Creek, Role Models. Atherton Tablelands, Queensland Your task Indigenous involvement in the Defence of Australia in World War 2 Your task is to look at the sources presented on the next pages, and to use them to answer Who was involved? the sorts of key questions that are part of any What did they do? historical inquiry. You can use a table like this: When did they do it? Conclusion Where did they do it? When you have completed your summary table Why did they do it? from all the sources decide on your answers to these questions: What were the impacts of the involvement? Did Indigenous Australians show good What were the consequences of the involvement? citizenship during the war? Did Indigenous people provide good role models that we could follow today? Further Reading Did non-Indigenous Australians show good citizenship towards Indigenous Australians? Ball, Desmond. Aborigines in the defence of Australia. -

Defgram 182/2018 Incoming Defence Senior Leadership Team Announced

UNCONTROLLED IF PRINTED UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defence Active DEFGRAM 182/2018 Issue date: 16 April 2018 Expiry date: 13 July 2018 INCOMING DEFENCE SENIOR LEADERSHIP TEAM ANNOUNCED Incoming Chief of the Defence Force, Vice Chief of the Defence Force, Chief of Navy, Chief of Army and Chief Joint Operations Announced 1. Further to the Prime Minister's press conference, the incoming Defence Senior Leadership Team has now been announced. 2. Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, AO, DSC on promotion to General, will be appointed as the Chief of the Defence Force. Lieutenant General Campbell will be reaching this milestone after 32 years of service with the Australian Regular Army. His extensive military career has included a number of senior roles, such as Head Military Strategic Commitments, Deputy Chief of Army and Commander Joint Agency Task Force. In his current appointment, as Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Campbell has been a driving force in cultural reform, with a specific focus on achieving equal opportunities and addressing domestic violence. His well-respected military career, in addition to his experience working in National Security, for the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, make him ideally suited to lead the organisation in further reform and in embedding One Defence. 3. Vice Admiral David Johnston, AO, RAN will be appointed as the Vice Chief of the Defence Force. Vice Admiral Johnston has been serving with the Royal Australian Navy since 1978 and has recently been awarded his Federation Star. His highly esteemed military career has seen him in a number of senior appointments, including Deputy Chief Joint Operations, Commander Border Protection Command and most recently, Chief Joint Operations.