Review of Environmental and Regulatory Processes 2. Review of the Fisheries Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipatshimun 4E Trimestre 2008.Pdf

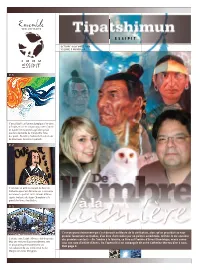

OCTOBRE-NOVEMBRE 2008 VOLUME 5 NUMÉRO 4 P. 5 C’est officiel ! La flamme olympique s’en vient à Essipit, et lors de son passage, notre Conseil de bande livrera un message bien spécial que lui a demandé de transmettre l’une des quatre Premières Nations hôtes des Jeux de Vancouver, la nation Squamish. P. 7 C’est dans un petit restaurant de Baie Ste- Catherine que s’est déroulée une « rencontre au sommet » portant sur la Grande Alliance signée tout près de là par Champlain et le grand chef innu, Anadabijou. P. 3 C’est un grand événement qui s’est déroulé au Musée de la civilisation, alors qu’on procédait au tout premier lancement au Québec, d’un livre d’art réalisé par un peintre autochtone. Intitulé Je me souviens L’entente entre Essipit et Boisaco fait des petits : des premiers contacts – De l’ombre à la lumière, ce livre est l’œuvre d’Ernest Dominique, mieux connu déjà des mesures d’accommodement sont sous son nom d’artiste d’Aness. On l’aperçoit ici en compagnie de notre Catherine Moreau bien à nous. en place prévoyant notamment, une Voir page 6 relocalisation du site traditionnel du lac Maigre vers le lac Mongrain. Tipatshimun ENTENTE AVEC BOISACO ESSIPIT DÉPOSE DES AVIS DE PRÉFAISABILITÉ Nos valeurs sont-elles Deux projets de mini-centrales respectées? en Haute-Côte-Nord ans une lettre datée du 16 octobre communément appelé Les portes de l’enfer. D2008, le chef Denis Ross du Conseil Il aurait une puissance installée de 36 MW et des Innus Essipit, avise le préfet Jean-Ma- une production annuelle de 119 400 MWh. -

Bottin Des Organismes Du Lac-Saint-Jean PREMIÈRE ÉDITION | 2020-2021

Bottin des organismes du Lac-Saint-Jean PREMIÈRE ÉDITION | 2020-2021 Alexis Brunelle-Duceppe Bottin des organismes du Lac-Saint-Jean 1 Première éditionDéputé | 2020-2021 de Lac-Saint-Jean Mot du député Chères citoyennes, Chers citoyens, Ouf! Quelle année mouvementée vivons-nous…! Toutes et tous ont fait des sacrifices pour passer à travers ces temps difficiles et bon nombre de gens dévoués ont pris le temps d’aider leur prochain. Que ce soit en se portant volontaire pour travailler dans les CHSLD, en faisant l’épicerie pour leurs voisins ou tout simplement en restant à la maison, les Jeannois et les Québécois ont montré à quel point ils avaient à cœur leur communauté. Cet engagement envers notre milieu, il est aussi porté au jour le jour par les travailleuses et les travailleurs des organismes communautaires. Ces gens œuvrent pour le bien commun et offrent des services de première ligne à tous les citoyens, quelle que soit leur situation socio-économique. Je suis très fier du livret que vous tenez entre vos mains, car il vous permettra d’entrer en contact avec des personnes qui peuvent vous aider. Cette première édition du Bottin des organismes répertorie donc les nombreux organismes de la circonscription Lac-Saint-Jean. De plus, vous remarquerez que la feuille centrale de ce document est détachable et peut servir à m’écrire gratuitement. Comme toujours, je m’engage à répondre à vos lettres et je suis toujours à l’affût des idées que vous me soumettez. D’ailleurs, je suis heureux de vous présenter les dessins gagnants du concours de la Fête nationale. -

Rapport Annuel 2017-2018

Couverture La couverture du rapport annuel 2017-2018 rappelle le Tshishtekahikan, le calendrier 2018-2019, qui souligne l’Année internationale des droits des peuples autochtones qui sera célébrée en 2019. Il s’agit d’une opportunité pour rappeler le caractère incontournable de la reconnaissance des droits des Premières Nations et pour sensibiliser à l’importance de la Déclaration des Nations Unies sur les droits des peuples autochtones. Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan 1671, rue Ouiatchouan Mashteuiatsh (Québec) G0W 2H0 Téléphone : 418 275-2473 Courriel : [email protected] Internet : www.mashteuiatsh.ca © Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan, 2018 Tous droits réservés. Toute reproduction ou diffusion du présent document, sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit, même partielle, est strictement interdite sans avoir obtenu, au préalable, l’autorisation écrite de Pekuakamiulnuatsh Takuhikan. 2 TABLE DES MATIÈRES Katakuhimatsheta Conseil des élus ........................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Tshitshue Takuhimatsheun Direction générale ...............................................................................................................................................................................................23 Katshipahikanish kamashituepalitakanitsh pakassun Ilnu Tshishe Utshimau Bureau du développement de l'autonomie gourvernementale ..................................................................................................26 -

Tipatshimun Fevrier 2015 Essipit Complet.Pdf

ESSIPIT Page 2 C’est le 20 novembre qu’avait lieu l’évé- nement portes ouvertes de la nouvelle section du Centre administratif de la communauté d’Essipit. Page 3 Lancement du calendrier « ESHE » du Regroupement PETAPAN. Pages 4 et 5 Pascale Chamberland, Mélissa Ross, Annie Ashini et Johanne Bouchard se sont bien amusées. Le Conseil de bande honore certains de ses employés lors de son party de Noël. Page 7 Une belle année qui se termine avec la Une équipe de la Première Nation des Innus Essipit effectue des fouilles archéologiques de sauvetage au venue du père Noël. site « Lavoie » des Bergeronnes. Tipatshimun JOURNÉE PORTES OUVERTES Visite de la nouvelle aile du CentreCentre administratifadministratif À ll’entrée’entrée ddee llaa nnouvelleouvelle ppartie,artie, lleses eemployésmployés aaccueillentccueillent nnosos vvisiteurs.isiteurs. JJean-Françoisean-François BBoulianne,oulianne, UUnn bbuffetuffet a éétété sserviervi ddansans llaa nnouvelleouvelle ssallealle ddee rréunionéunion « UUtatakuntatakun »».. LLucuc CChartré,hartré, FFlorencelorence PParcoretarcoret eett PPierreierre TTremblay.remblay. Plus de 60 personnes ont par- De fond en comble de réunion appelée Utatakun et un étaient conviés à un buffet disposé ticipé à la visite de la nouvelle Dès 15 h 30, des invités se sont poste de service où sont situés une dans la salle Utatakun. Lorsque tous aile du Centre administratif Innu présentés dans le hall d’entrée où ils photocopieuse et une imprimante. furent arrivés, le chef Dufour les a Tshitshe Utshimau qui a eu lieu furent accueillis -

Continuation of the Negotiations with the Innu

QUEBECERS and the INNU CONTINUATION OF THE NEGOTIATIONS WITH THE INNU AGREEMENT-IN-PRINCIPLE WORKING TOGETHER TO ACHIEVE A TREATY Québec Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones Québec HOW TO PARTICIPATE IN THE NEGOTIATIONS The Government of Québec has put in place a participation mechanism that allows the populations of the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean and Côte-Nord regions to make known their opinion at the negotiating table. Québec’s negotiations team includes a representative of the regions who attends all of the negotiation sessions. He is the regions’ spokesperson at the negotiating table. The representative of the regions can count on the assistance of one delegate in each of the regions in question. W HAT IS THE RO L E OF THE REP RES ENTATIV E O F THE REGIO NS AND THE DELEGATES? 1 To keep you informed of the progress made in the work of the negotiating table. 2 To consult you and obtain your comments. 3 To convey your proposals and concerns to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and to the special negotiator for the Government of Québec. WHAT IS THE AGREEM ENT-IN-P RINCIPLE? The agreement-in-principle reached by the Government of Québec, the Government of Canada and the First Nations of Betsiamites, Essipit, Mashteuiatsh and Nutashkuan will serve as a basis for negotiating a final agreement that will compromise a treaty and complementary agreements. In other words, it is a framework that will orient the pursuit of negotiations towards a treaty over the next two years. WHY NEGOTIATE? Quebecers and the Innu have lived together on the same territory for 400 years without ever deciding on the aboriginal rights of the Innu. -

Synthèse De L'entente De Principe Avec Les Innus La

Synthèse de l'entente de principe avec les Innus La © LOUIS GAGNON/TQ 1 nég ciation Pourquoi Parce que l’incertitude juridique entourant les négocier? droits ancestraux des nations autochtones nuit au développement de vastes régions du Québec. Les tribunaux ont en effet établi qu’une nation autochtone a des droits particuliers sur un territoire où elle était présente à l’arrivée des Européens et qu’elle a continué de fréquenter depuis. Le problème, c'est que ces « droits ancestraux » n’ont jamais été définis. Québécois et Innus cohabitent donc sur le même territoire sans jamais avoir clarifié ces droits, ce qui entraîne des poursuites judiciaires et nuit au développement régional ainsi qu’aux bonnes relations entre les deux communautés. Pour remédier à cette situation, les gouvernements et certaines communautés innues ont choisi de négocier. La négociation devrait permettre l'atteinte de quatre objectifs : • reconnaître les droits ancestraux des Innus; • définir les effets et les modalités d'application des droits des Innus afin d'obtenir une certitude quant à leur exercice; • permettre aux Innus d'assumer davantage de responsabilités et de prendre en charge leur propre destinée; • établir un équilibre et un rapport harmonieux entre les droits des Québécois et ceux des Innus. La négociation s’avère la meilleure façon d’établir, dans le respect mutuel, une nouvelle relation entre Québécois et Innus fondée sur le partenariat et la cohabitation. 2 ENSEMBLE VERS UN TRAITÉ © MARCEL GIGNAC/TQ ui négocie et où en est la négociation? Ce sont les premières nations innues, le gouvernement du Canada et le gouvernement du Québec qui sont engagés, Actuellement, sept des neuf communautés innues du Québec sont engagées dans une négociation territoriale depuis 1980, dans une avec les gouvernements du Québec et du Canada. -

Régional Ou Sous-Régional

Régional ou sous-régional Nom Organisme Bureau Fermé au public Services/activités annulés/reportés Ville ACSM Saguenay Chicoutimi AGL - LGBT 1 Roberval Association de la Fibromyalgie SLSJ Chicoutimi Association des Arthritiques SLSJ Chicoutimi Association des personnes handicapées Visuelles-02 Alma Association PANDA Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean Chicoutimi Les services sont suspendus. Télétravail: Kim Association Québecoise de la dysphasie alimente la page FaceBook et Joanie la nouvelle intervenante au Lac poursuit sa Association régionale pour les personnes épileptiques formation en ligne. Jonquière (Région 02) Jonquière Association Renaissance des personnes traumatisées Soutien téléphonique.Bonjour saisonniers crâniennes ARPTC spéciaux. Jonquière Télétravail. Communications par courriel, Autisme Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean 1 page Facebook et services téléphoniques. Roberval Calacs Entre Elles 1 Rejoindre par courriel. Chicoutimi Centre d'assistance et d'accompagnement aux 1 plaintes Chicoutimi Comité Enfaim 1 Jonquière Corporation des métiers d'Art SLSJ Télétravail. Possibilité de joindre par Jonquière courriel, téléphone, messagerie. Rencontre École nationale d'apprentissage par la marionnette sur plateformes virtuelles également (ÉNAM) 1 possibles. Alma Eurêko! Chicoutimi Havre du Fjord Centre de jour fermé. La Baie Information et référence 02 Jonquière Le Miens Chicoutimi Soutien téléphonique. Cessent visites à l'hôpital d'Alma et le sans rendez-vous de Les Habitations partagées du Saguenay mercredi est annulé Alma Maison de l'Espoir Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean 1 Toutes activités mars suspendues Chicoutimi Nom Organisme Bureau Fermé au public Services/activités annulés/reportés Ville Maison d'hébergement SOS Jeunesse Jonquière Moisson Saguenay Lac Saint-Jean Régional Nourri-Source Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean Régional Parkinson Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean Régional Soirée Musicale « pour un geste digne de Saguenéens et Jeannois pour les droits de la personne mémoire » est annulé pour le 21 mars et sera reporté à une date ultérieure Alma AGA reportée. -

Rapport Rectoverso

HOWSE MINERALS LIMITED HOWSE PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT – (APRIL 2016) - SUBMITTED TO THE CEAA 7.5 SOCIOECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT This document presents the results of the biophysical effects assessment in compliance with the federal and provincial guidelines. All results apply to both jurisdictions simultaneously, with the exception of the Air Quality component. For this, unless otherwise noted, the results presented/discussed refer to the federal guidelines. A unique subsection (7.3.2.2.2) is provided which presents the Air Quality results in compliance with the EPR guidelines. 7.5.1 Regional and Historical Context The nearest populations to the Project site are found in the Schefferville and Kawawachikamach areas. The Town of Schefferville and Matimekush-Lac John, an Innu community, are located approximately 25 km from the Howse Property, and 2 km from the Labrador border. The Naskapi community of Kawawachikamach is located about 15 km northeast of Schefferville, by road. In Labrador, the closest cities, Labrador City and Wabush, are located approximately 260 kilometres from the Schefferville area (Figure 7-37). The RSA for all socioeconomic components includes: . Labrador West (Labrador City and Wabush); and . the City of Sept-Îles, and Uashat and Mani-Utenam. As discussed in Chapter 4, however, Uashat and Mani-Utenam are considered within the LSA for land-use and harvesting activities (Section 7.5.2.1). The IN and NCC are also considered to be within the RSA, in particular due to their population and their Aboriginal rights and land-claims, of which an overview is presented. The section below describes in broad terms the socioeconomic and historic context of the region in which the Howse Project will be inserted. -

Benjamin Ross, Pierre Ross-Fortin Et Pierre-Marc Gravel Représentaient Essipit À La Quatrième Édition De La Dictée Innu

MAI-JUIN 2008 VOLUME 5 NUMÉRO 2 P. 8 L’aire de répartition du caribou des bois ne cesse de reculer vers le nord, à tel point que cette espèce n’existe pratiquement plus au sud du St-Laurent, si ce n’est dans le Parc de la Gaspésie. Mais le caribou ne s’en va pas : il meurt! P. 10 Benjamin Ross, Pierre Ross-Fortin et Pierre-Marc Gravel représentaient Essipit à la quatrième Le Centre d’information et de réservations édition de la Dictée innu / Pakunu e mashinaitshenanut qui, comme chaque année, avait lieu à des Entreprises Essipit a remporté l’or, soit un Uashat. Pierre-Marc et Benjamin ont décroché respectivement la première et deuxième place premier prix national dans la catégorie dans la catégorie innue langue seconde. Une fierté qui rejaillit sur toute la Première Nation « services touristiques », à l’occasion des plus récents Grands Prix du tourisme québécois d’Essipit. P. 5 tenus au Palais des congrès de Montréal. Tipatshimun ENSEMBLE VERS UN TRAITÉ Une obligation de résultat serait appelé à trancher à titre C’est à l’occasion de propriétaire foncier. « de rencontres d’échange et d’informa- Autre question : où les tion tenues les 4 et 5 mai municipalités trouveront-elles derniers, que les mem- de meilleurs alliés pour les bres, membres apparen- aider à mettre en place leur tés et employés d’Essipit, propre plan d’aménagement, ont posé une foule de tel que stipulé dans le Livre questions et formulé vert? Essipit y travaille pour leurs commentaires en sa part depuis plus de cinq regard de la conduite ans! Au lieu de s’affronter sur des négociations et plus un sujet aussi vital pour notre particulièrement en ce région, c’est ensemble, Innus qui a trait au régime et Québécois réunis, que nous territorial. -

CANADA PROVINCE DE QUÉBEC DISTRICT DE MONTRÉAL NO. R-3677-2008 RÉGIE DE L'énergie HYDRO-QUÉBEC (Ci-Après Le « DISTRIBUT

RÉGIE DE L’ÉNERGIE CANADA PROVINCE DE QUÉBEC DISTRICT DE MONTRÉAL NO. R-3677-2008 HYDRO-QUÉBEC (Ci-après le « DISTRIBUTEUR») Demanderesse Et CONSEIL DE LA NATION INNU MATIMEKUSH-LAC JOHN, un Conseil de bande reconnu en vertu de la Loi sur les Indiens, ayant son siège dans la réserve de Matimekush, Case postale 1390 à Schefferville (Québec), G0G 2T0 (Ci-après le «CNIMLJ») Intervenant MÉMOIRE DU CONSEIL DE LA NATION INNU MATIMEKUSH-LAC JOHN MÉMOIRE DU CONSEIL DE LA NATION INNU MATIMEKUSH-LAC JOHN Présenté à la Régie de l’Énergie Dans le cadre de la DEMANDE DU DISTRIBUTEUR RELATIVE À L’ÉTABLISSEMENT DES TARIFS D’ÉLECTRICITÉ POUR L’ANNÉE 2009-2010 DOSSIER : R-3677-2008 30 octobre 2008 Mémoire du CNIMLJ, 30 octobre 2008 No dossier : R-3677-2008 AVANT-PROPOS Ce mémoire est présenté par le CNIMLJ à la Régie de l’Énergie dans le cadre de la demande du Distributeur relative à l’établissement des tarifs d’électricité pour l’année 2009-2010. Par conséquent, ce mémoire s’inscrit uniquement dans ce processus et ne limite en aucun cas les droits et recours reconnus par les gouvernements et les tribunaux à la communauté de Matimekush-Lac John. De plus, ce document ne peut être considéré comme le seul et unique moyen pour la communauté d’exprimer son opinion et de faire valoir ses droits et ne constitue pas un appui formel audit projet ni conditionnel au contenu du présent mémoire. Finalement, le contenu et les termes du présent document ne doivent en aucune façon être interprétés de manière à porter atteinte au titre aborigène de la communauté et à ses droits ancestraux ou de porter préjudice aux négociations territoriales en cours. -

Profil Socio-Économique Des Localités De La Mrc Du Domaine-Du-Roy

PROFIL SOCIO-ÉCONOMIQUE DES LOCALITÉS DE LA MRC DU DOMAINE-DU-ROY effectué pour le compte de LA SOCIÉTÉ D'AIDE AU DÉVELOPPEMENT DES COLLECTIVITÉS (SADC) LAC-SAINT-JEAN OUEST INC. présenté par Jean-François Tremblay Baccalauréat en Sciences politiques Maitrise en Sociologie Novembre 2003 Recherchiste: Jean-François Tremblay (Baccalauréat en sciences politiques, maitrise en sociologie) Compilation et rédaction: Jean-François Tremblay (Baccalauréat en sciences politiques, maitrise en sociologie) Sous la direction de: M. Serge Desgagné, Directeur général SADC du Lac-Saint-Jean Ouest inc. M. Steeve Larouche Agent de développement local SADC du Lac-Saint-Jean Ouest inc. Traitement de texte: Mélissa Girard et Véronick Bussière Stagiaires SADC du Lac-Saint-Jean Ouest inc. II REMERCIEMENTS Nous tenons à porter une attention particulière à tous les organismes, ministères ou autres intervenants qui ont collaboré à la réalisation de ce profil socio-économique. Par leur contribution, ces derniers nous ont permis d'améliorer nos connaissances sur les diverses réalités vécues à l'intérieur de chaque municipalité du territoire couvert par la SADC Lac-Saint-Jean Ouest inc., soit les localités de la MRC du Domaine-du-Roy. De ces partenaires, nous remercions plus particulièrement: Institut de la statistique du Québec; Ministère de l’Emploi, de la Solidarité Sociale et de la Famille (Sécurité du revenu); Centre local de développement du Domaine-du-Roy; Pays-des-Bleuets; Développement économique Canada; Développement des ressources humaines Canada (Jonquière); Modules interactifs géographiques (MIG) du Réseau des SADC du Québec; M.R.C. du Domaine-du-Roy; Municipalités et villes de La Doré, Chambord, Sainte-Hedwidge, Saint-François-de- Sales, Lac-Bouchette, Roberval, Saint-Félicien, Mashteuiatsh, Saint-Prime et Saint-André-du-Lac-Saint-Jean; Statistiques Canada; Atlas géographique du Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean; Association touristique régionale du Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. -

Management Plan for Archipelago National Park Reserve of Canada

Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve of Canada Management Plan 2014 Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve of Canada 2014 MANAGEMENT PLAN The Parks Canada Charter OUR MANDATE On behalf of the people of Canada, we protect and present nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage, and foster public understanding, appreciation and enjoyment in ways that ensure the ecological and commemorative integrity of these places for present and future generations. OUR ROLE We are guardians of the national parks, the national historic sites and the national marine conservation areas of Canada. We are guides to visitors the world over, opening doors to places of discovery and learning, reflection and recreation. We are partners, building on the rich traditions of our Aboriginal people, the strength of our diverse cultures and our commitments to the international community. We are storytellers, recounting the history of our land and our people - the stories of Canada. OUR COMMITMENTS To protect, as a first priority, the natural and cultural heritage of our special places and ensure that they remain healthy and whole. To present the beauty and significance of our natural world and to chronicle the human determination and ingenuity which have shaped our nation. To celebrate the legacy of visionary Canadians whose passion and knowledge have inspired the character and values of our country. To serve Canadians, working together to achieve excellence guided by values of competence, respect and fairness. 2 Mingan Archipelago