Does the Glass Ceiling Exist? a Longitudinal Study of Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Contributing Editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy

GETTING THROUGH THE DEAL Initial Public Offerings Initial Public Offerings Public Initial Contributing editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy 2017 Law Business Research 2017 © Law Business Research 2016 Initial Public Offerings 2017 Contributing editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP Publisher Law The information provided in this publication is Gideon Roberton general and may not apply in a specific situation. [email protected] Business Legal advice should always be sought before taking Research any legal action based on the information provided. Subscriptions This information is not intended to create, nor does Sophie Pallier Published by receipt of it constitute, a lawyer–client relationship. [email protected] Law Business Research Ltd The publishers and authors accept no responsibility 87 Lancaster Road for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although Senior business development managers London, W11 1QQ, UK the information provided is accurate as of July 2016, Alan Lee Tel: +44 20 3708 4199 be advised that this is a developing area. [email protected] Fax: +44 20 7229 6910 Adam Sargent © Law Business Research Ltd 2016 Printed and distributed by [email protected] No photocopying without a CLA licence. Encompass Print Solutions First published 2015 Tel: 0844 2480 112 Dan White Second edition [email protected] ISSN 2059-5484 © Law Business Research 2016 CONTENTS Global overview 5 Japan 51 Joshua Ford -

FRC Board Diversity and Effectiveness in FTSE 350

Leadership Institute Board Diversity and Effectiveness in FTSE 350 Companies July 2021 Acknowledgements Report written by: Mary Akimoto, Osman Anwar, Molly Broome, Dragos Diac, Dr Randall S Peterson, Dr Sergei Plekhanov, Simon Osborne and Vyla Rollins We thank the following individuals on the joint LBSLI/SQW research team for their contributions to this research: • Ruth Cluness, LBSLI • Tom Gosling, LBSLI • Brent Hamerla, LBSLI • Letitia Joseph, LBSLI • Barbara Moorer, LBSLI • Andrei Visiteu, LBSLI • Desi Zlatanova, LBSLI We also give a special thank you to our team of research interviewers: • Eva Beazley • Helen Beedham • Christine de Largy • Kathryn Gordon • Dr JoEllyn Prouty McLaren The London Business School Leadership Institute expresses its thanks to all of our stakeholder and collaborators, who supported our research efforts. We would like to express our specific gratitude to the following individuals, for their invaluable guidance, comments, suggestions and support throughout this project: Kit Bingham, Charlie Brown, Gerry Brown, Sue Clark, Louis Cooper, John Dore, Lisa Duke, Roshy Dwyer, Farrer & Co (Anisha Birk, Natalie Rimmer, Peter Wienand), Louise Fowler, Dr Julian Franks, Dr Karl George MBE, Dr Tom Gosling, Dr Byron Grote, Fiona Hathorn, Jonathan Hayward, Susan Hooper, Dr Ioannis Ioannou, Bernhard Kerres, LBS Accounts department (Akposeba Mukoro, Janet Nippard), LBS Advancement department (Luke Ashby, Susie Balch, Nina Bohn, Ian Frith, Sarah Jeffs, Maria Menicou), LBS Executive Education, LBS Research & Faculty Office and -

Examining Drivers of Trading Volume in European Markets

Received: 28 July 2016 Accepted: 19 December 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ijfe.1608 RESEARCH ARTICLE Examining drivers of trading volume in European markets Bogdan Batrinca | Christian W. Hesse | Philip C. Treleaven Department of Computer Science, Abstract University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK This study presents an in‐depth exploration of market dynamics and analyses potential drivers of trading volume. The study considers established facts from Correspondence Bogdan Batrinca, Department of the literature, such as calendar anomalies, the correlation between volume and Computer Science, University College price change, and this relation's asymmetry, while proposing a variety of time London, Gower Street, London WC1E series models. The results identified some key volume predictors, such as the 6BT, UK. Email: [email protected] lagged time series volume data and historical price indicators (e.g. intraday range, intraday return, and overnight return). Moreover, the study provides empirical evi- Funding information dence for the price–volume relation asymmetry, finding an overall price asymme- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) UK try in over 70% of the analysed stocks, which is observed in the form of a moderate overnight asymmetry and a more salient intraday asymmetry. We conclude that JEL Classification: C32; C52; C58; G12; volatility features, more recent data, and day‐of‐the‐week features, with a notable G15; G17 negative effect on Mondays and Fridays, improve the volume prediction model. KEYWORDS asymmetric models, behavioural finance, European stock market, feature selection, price volume relation, trading volume 1 | INTRODUCTION which was $63tn in 2011 (World Federation of Exchanges, 2012) and $49tn in 2012 (World Federation of Exchanges, This study investigates the drivers affecting the trading 2013). -

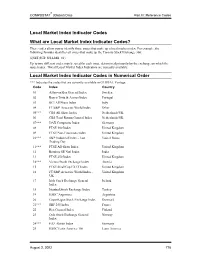

Local Market Index Indicator Codes in Numerical

® COMPUSTAT (Global) Data Part III: Reference Codes Local Market Index Indicator Codes What are Local Market Index Indicator Codes? These codes allow you to identify those issues that make up a local market index. For example, the following formula identifies all issues that make up the Toronto Stock Exchange 300: @SET($GI+$FI,LMII=81) Up to two different codes may be used for each issue, determined primarily by the exchange on which the issue trades. Not all Local Market Index Indicators are currently available. Local Market Index Indicator Codes in Numerical Order *** Indicates the codes that are currently available in GLOBAL Vantage Code Index Country 01 Affarsvarlden General Index Sweden 02 Banco Totta & Acores Index Portugal 03 BCI All Share Index Italy 04 FT/S&P Actuaries World Index Other 05*** CBS All Share Index Netherlands/UK 06 CBS Total Return General Index Netherlands/UK 07*** DAX Composite Index Germany 08 FTSE 100 Index United Kingdom 09 FTSE Non-Financials Index United Kingdom 10*** S&P Industrial Index - Last United States Trading Day 11*** FTSE All-Share Index United Kingdom 12 Bombay SE Natl Index India 13 FTSE 250 Index United Kingdom 14*** Vienna Stock Exchange Index Austria 15 FTSE SmallCap EX IT Index United Kingdom 16 FT/S&P Actuaries World Index - United Kingdom UK 17 Irish Stock Exchange General Ireland Index 18 Istanbul Stock Exchange Index Turkey 19 HSBC Argentina Argentina 20 Copenhagen Stock Exchange Index Denmark 21*** SBF 250 Index France 22 Hex General Index Finland 23 Oslo Stock Exchange General Norway -

Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics

Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics Diethelm Würtz Andrew Ellis Yohan Chalabi Rmetrics Association & Finance Online R/Rmetrics eBook Series R/Rmetrics eBooks is a series of electronic books and user guides aimed at students and practitioner who use R/Rmetrics to analyze financial markets. A Discussion of Time Series Objects for R in Finance (2009) Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2009 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz Basic R for Finance (2010), Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Longhow Lam, Andrew Ellis Chronological Objects with Rmetrics (2010), Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis Portfolio Optimization with R/Rmetrics (2010), Diethelm Würtz, William Chen, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm W?rtz, Andrew Ellis, Yohan Chalabi Indian Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm Würtz, Mahendra Mehta, Andrew Ellis, Yohan Chalabi Asian Option Pricing with R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm Würtz R/Rmetrics Singapore 2010 Proceedings of the Singapore Workshop 2010 Editors Diethelm Würtz, Mahendra Mehta, David Scott, Juri Hinz R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2011 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer School and Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz III tinn-R Editor (2010) José Cláudio Faria, Philippe Grosjean, Enio Galinkin Jelihovschi and Ri- cardo Pietrobon R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2011 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer Scholl and Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2012 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer Scholl and Workshop 2012 Editor Diethelm Würtz Topics in Empirical Finance with R and Rmetrics (2013), Patrick Hénaff FINANCIAL MARKET DATA FOR R/RMETRICS DIETHELM WÜRTZ ANDREW ELLIS YOHAN CHALABI RMETRICS ASSOCIATION &FINANCE ONLINE Series Editors: Prof. -

FTSE UK Index Series Family

Benchmark Statement FTSE UK Index Series Family September 2021 v1.6 FTSE Russell An LSEG Business | FTSE UK Index Series Family This benchmark statement is provided by FTSE International Limited as the administrator of the FTSE UK Index Series Family. It is intended to meet the requirements of EU Benchmark Regulation (EU2016/1011) and the supplementary regulatory technical standards and the retained EU law in the UK (The Benchmarks (Amendment and Transitional Provision) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019) that will take effect in the United Kingdom at the end of the EU Exit Transition Period on 31 December 2020. The benchmark statement should be read in conjunction with the FTSE UK Index Series Ground Rules and other associated policies and methodology documents. Those documents are italicised whenever referenced in this benchmark statement and are included as an appendix to this document. They are also available on the FTSE Russell website (www.ftserussell.com). References to “BMR” or “EU BMR” in this benchmark statement refer to Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on indices used as benchmarks in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds. References to “DR” in this benchmark statement refer to Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1643 of 13 July 2018 supplementing Reguorlation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards specifying further the contents of, and cases where updates are required to, the benchmark statement to be published by the administrator of a benchmark. -

FTSE 350 Climate Change Report 2013

01 Are UK companies prepared for the international impacts of climate change? FTSE 350 Climate Change Report 2013 9 October 2013 Report writer and global advisor 02 03 The evolution of CDP Contents With great pleasure, CDP announced an exciting change this year. CEO Foreword 4 Executive Summary 6 Over ten years ago CDP pioneered the only global disclosure system for companies to report their environmental impacts and strategies to investors. In that time, 2013 Climate Performance and Disclosure Leaders 8 and with your support, CDP has accelerated climate change and natural resource 2013 Leadership Criteria 10 issues to the boardroom and has moved beyond the corporate world to engage Investor insight - the “Aiming for A” coalition 11 with cities and governments. FTSE 350 companies have a global footprint 12 The CDP platform has evolved significantly, supporting multinational purchasers Companies’ focus on climate change risks and opportunities needs broadening 12 to build more sustainable supply chains. It enables cities around the world to exchange information, take best practice action and build climate resilience. We Scientific Insight - Professor Sir Brian Hoskins 17 assess the climate performance of companies and drive improvements through Companies’ understanding of their value chain is limited 20 shareholder engagement. Corporate insight - Reckitt Benckiser 22 Our offering to the global marketplace has expanded to cover a wider spectrum of FTSE 100 companies have a more sophisticated response the earth’s natural capital, specifically water and forests, alongside carbon, energy to climate change than FTSE 250 companies 23 and climate. Preparing for climate change: Comparing FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 companies 26 For these reasons, we have outgrown our former name of the Carbon Disclosure PwC commentary – Celine Herweijer 28 Project and rebranded to CDP. -

Lowland Investment Company

Lowland Investment Company plc Registered as an investment company in England and Wales Registration number: 670489 Registered office: 201 Bishopsgate, London EC2M 3AE. SEDOL/ISIN number: 0536806/GB00 053680 62 London Stock Exchange (TDIM) Code: LWI Global Intermediary Identification Number (GIIN): 2KBHLK.99999.SL826 Legal Entity Identifier (LEI): 2138008RHG5363FEHV19 Telephone: 0800 832 832 Email: [email protected] www.lowlandinvestment.com Lowland Investment Company plc – Annual Report for the year ended 30 September 2018 Lowland Investment Company plc Shareholder Shareholder Communication Communication Awards Awards 2017 2018 WINNER WINNER Winner UK Equity Income Fund of the Year This report is printed on cocoon silk 60% recycled, a recycled paper containing 60% recycled waste and 40% virgin fibre and manufactured at a mill certified with ISO 14001 environmental management standard. The pulp used in this product is bleached using an Elemental Chlorine Free process (ECF). The FSC® logo identifies products which contain wood from well managed forests certified in JHI9222/2018 accordance with the rules of the Forest Stewardship Council®. Annual Report 2018 Typeset by 2112 Communications, London. Printed by PurePrint JHI9222/2018 Lowland Investment Company plc Annual Report 2018 Contents Strategic Report Corporate Report Key Data 3 Report of the Directors 26 Historical Performance 4 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 27 Chairman’s Statement 5-6 Directors’ Remuneration Report 28-29 Performance 5 Corporate Governance Statement -

Analysis of Key Drivers of Trading Performance

Analysis of Key Drivers of Trading Performance Bogdan Batrinca A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University College London Department of Computer Science University College London 2016 2 Declaration I, Bogdan Batrinca, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. …………………………………………… Bogdan Batrinca 3 Abstract This thesis is an applied study for understanding the key factors of trading volume, providing an in-depth investigation of liquidity demand and market impact. This research was conducted in collaboration with Deutsche Bank and presents a series of empirical studies, which examine several underlying factors affecting trading volume when executing orders algorithmically in the European equity markets, which ultimately translates into trading performance and liquidity modelling. This addresses several aspects: the size of the liquidity demand relative to the predicted or actual volumes traded in the market; the choice of execution strategy given the liquidity properties of the stock; and the timing of the trade, given the market circumstances and released or anticipated company news. All of these reflect the investment skill of the portfolio manager and the execution skill of the trader, and to some extent the quality of the execution algorithm being used. The motivation is to investigate various factors that adversely affect the trading performance of algorithms, causing them to have excessive market impact or to under-participate when the market experiences periods of higher volatility. Although measuring the market fairness and efficiency is a crucial component for understanding the execution style and improving trading performance, the research into how to model and decompose trading performance requires further investigation. -

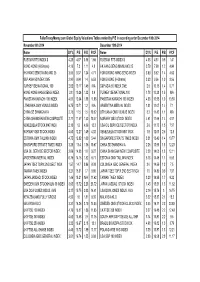

Link to the Full List

FullerTreacyMoney.com Global Equity Valuations Tables ranked by P/E in ascending order December 10th 2014 November 6th 2014 December 10th 2014 Name DY% P/E P/B P/CF Name DY% P/E P/B P/CF RUSSIAN RTS INDEX $ 4.28 4.87 0.56 1.66 RUSSIAN RTS INDEX $ 4.08 4.81 0.5 1.41 HONG KONG (H-Shares) 4.16 7.3 1.11 4.8 HK HANG SENG MAINLAND 25 3.79 7.98 1.2 4.94 HK HANG SENG MAINLAND 25 3.95 8.37 1.34 4.71 HONG KONG HANG SENG INDEX 3.89 8.62 1.4 4.63 S&P ASIA 50 INDEX CME 2.92 9.94 1.4 6.53 HONG KONG (H-Shares) 3.83 9.96 1.3 8.56 TURKEY ISE NATIONAL 100 2.02 10.17 1.45 N/A S&P ASIA 50 INDEX CME 2.9 10.15 1.4 6.77 HONG KONG HANG SENG INDEX 3.8 10.24 1.33 8.9 TURKEY ISE NATIONAL 100 1.78 10.28 1.5 N/A PAKISTAN KARACHI 100 INDEX 4.81 10.64 1.88 11.86 PAKISTAN KARACHI 100 INDEX 4.66 10.95 1.9 10.38 LITHUANIA OMX VILNIUS INDEX 6.75 10.71 1.2 N/A ARGENTINA MERVAL INDEX 1.01 11.07 1.4 7.1 CHINA SE SHANGHAI A 2.75 11.5 1.5 10.52 LITHUANIA OMX VILNIUS INDEX 8.3 11.42 1.1 N/A CHINA SHANGHAI NEW COMPOSITE 2.77 11.57 1.52 10.47 NORWAY OBX STOCK INDEX 4.61 11.66 1.4 4.07 VENEZUELA STOCK MKT INDX 2.15 12 4.56 13.3 USA OIL SERVICE SECTOR INDEX 2.6 11.70 1.5 7.57 NORWAY OBX STOCK INDEX 4.53 12.27 1.49 4.32 VENEZUELA STOCK MKT INDX 1.8 12.60 2.5 12.8 ESTONIA OMX TALLINN INDEX 4.75 12.82 1.09 5.44 SINGAPORE STRAITS TIMES INDEX 3.31 13.49 1.4 10.77 SINGAPORE STRAITS TIMES INDEX 3.29 13.4 1.36 10.67 CHINA SE SHANGHAI A 2.26 13.98 1.8 12.23 USA OIL SERVICE SECTOR INDEX 2.06 14.03 1.8 9.27 CHINA SHANGHAI NEW COMPOSITE 2.28 14.03 1.8 12.11 ARGENTINA MERVAL INDEX 0.79 14.15 1.82 9.71 ESTONIA OMX TALLINN INDEX 5.18 14.49 1.1 5.58 JAPAN TSE2 TOPIX 2ND SECT INDX 1.57 14.7 0.86 8.28 COLOMBIA IGBC GENERAL INDEX 3.6 14.55 1.3 7.5 TAIWAN TAIEX INDEX 3.21 15.01 1.7 9.85 JAPAN TSE2 TOPIX 2ND SECT INDX 1.5 14.89 0.9 7.97 JAPAN JASDAQ: STOCK INDEX 1.46 15.21 N/A 11.62 TAIWAN TAIEX INDEX 3.23 14.95 1.7 9.22 SWEDEN OMX STOCKHOLM 30 INDEX 3.65 15.72 2.23 23.72 JAPAN JASDAQ: STOCK INDEX 1.45 15.51 1.3 11.62 USA DOW JONES INDUS. -

FTSE UK Index Series Ground Rules Following the March Quarterly Review and Will Become Effective from the June Annual Review

Ground Rules FTSE UK Index Series v15.1 ftserussell.com An LSEG Business June 2021 Contents 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Management Responsibilities ..................................................................... 5 3.0 FTSE Russell Index Policies ........................................................................ 7 4.0 Security Inclusion Criteria ........................................................................... 9 5.0 Nationality ....................................................................................................11 6.0 Screens Applied to Eligible Securities.......................................................13 7.0 Index Qualification Criteria .........................................................................15 8.0 Periodic Review of Constituents ................................................................17 9.0 Corporate Actions and Events ...................................................................22 10.0 Treatment of Dividends ...............................................................................25 11.0 Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) ..................................................26 12.0 Announcing Changes ..................................................................................27 Appendix A: Index Opening and Closing Hours .................................................28 Appendix B: Status of Indices ..............................................................................29 -

Weekly Advisor Alert by U.S. Global Investors, Inc

USFunds.com • October 28, 2016 Table of Contents Index Summary • Domestic Equity Market • Economy and Bond Market • Gold Market Energy and Natural Resources Market • Emerging Europe • China Region • Leaders and Laggards If you would like more information on our funds, feel free to contact our Institutional Services Team: Jerry Reed, Institutional Sales Specialist • 210.308.1250 • [email protected] Press Release: U.S. Global Investors Announces First Quarter 2017 Results Webcast Forget Everything You Know About Presidential Elections By Frank Holmes CEO and Chief Investment Officer U.S. Global Investors So here we are, 11 days before America picks its poison, with most national polls showing a win for Hillary Clinton. If she pulls it off, she’ll become not only the first woman and first first lady to rise to the country’s highest office but also the first Democrat to succeed another two-term Democrat since Martin Van Buren succeeded Andrew Jackson in 1837. She’ll also become the first to be under FBI investigation. Today we learned that the bureau is reopening her email case, mere days after WikiLeaks released even more damning files on the nominee. I find it interesting that back in July, eccentric internet entrepreneur Kim Dotcom predicted that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange would turn out to be Hillary’s “worst nightmare”—a prediction that has largely come true. Meanwhile, if Donald Trump manages an upset, he will become the oldest person ever to take the oath of office and the first to transition directly from the business world to the presidency without any past experience as a high-ranking government official (like William Howard Taft and Herbert Hoover) or military officer (like Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S.