FRC Board Diversity and Effectiveness in FTSE 350

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midwest Financial Brian Johnson, RFC 706 Montana Street Glidden, IA 51443 [email protected] 712-659-2156

Midwest Financial Brian Johnson, RFC 706 Montana Street Glidden, IA 51443 www.midwestfinancial.us [email protected] 712-659-2156 The SITREP for the week ending 08/06/2021 ***************************************************** SIT REP: n. a report on the current situation; a military abbreviation; from "situation report". In the markets: U.S. Markets: U.S. stocks recorded solid gains for the week and several indices hit record highs. The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 273 points finishing the week at 35,209, a gain of 0.8%. The NASDAQ retraced all of last week’s decline by rising 1.1% to close at 14,836. By market cap, the large cap S&P 500 rose 0.9%, while the mid cap S&P 400 and small cap Russell 2000 gained 0.5% and 1.0%, respectively. International Markets: Major international markets also finished the week solidly in the green. Canada’s TSX added 0.9%, while the United Kingdom’s FTSE 100 gained 1.3%. France’s CAC 40 and Germany’s DAX rose 3.1% and 1.4%, respectively. China’s Shanghai Composite added 1.8%, while Japan’s Nikkei rallied 2%. As grouped by Morgan Stanley Capital International, developed markets finished up 1.0% and emerging markets gained 0.7%. Commodities: Precious metals had a difficult week. Gold retreated -3.0% to $1763.10 per ounce, while Silver fell a steeper -4.8% to $24.33. West Texas Intermediate crude oil gave up all of the last two week’s gains, declining -7.7% to $68.28 per barrel. The industrial metal copper, viewed by some analysts as a barometer of world economic health due to its wide variety of uses, finished the week down -3%. -

Scanned Image

3130 W 57th St, Suite 105 Sioux Falls, SD 57108 Voice: 605-373-0201 Fax: 605-271-5721 [email protected] www.greatplainsfa.com Securities offered through First Heartland Capital, Inc. Member FINRA & SIPC. Advisory Services offered through First Heartland Consultants, Inc. Great Plains Financial Advisors, LLC is not affiliated with First Heartland Capital, Inc. In this month’s recap: the Federal Reserve eases, stocks reach historic peaks, and face-to-face U.S.-China trade talks formally resume. Monthly Economic Update Presented by Craig Heien with Great Plains Financial Advisors, August 2019 THE MONTH IN BRIEF July was a positive month for stocks and a notable month for news impacting the financial markets. The S&P 500 topped the 3,000 level for the first time. The Federal Reserve cut the country’s benchmark interest rate. Consumer confidence remained strong. Trade representatives from China and the U.S. once again sat down at the negotiating table, as new data showed China’s economy lagging. In Europe, Brexit advocate Boris Johnson was elected as the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and the European Central Bank indicated that it was open to using various options to stimulate economic activity.1 DOMESTIC ECONOMIC HEALTH On July 31, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates for the first time in more than a decade. The Federal Open Market Committee approved a quarter-point reduction to the federal funds rate by a vote of 8-2. Typically, the central bank eases borrowing costs when it senses the business cycle is slowing. As the country has gone ten years without a recession, some analysts viewed this rate cut as a preventative measure. -

2017 Contributing Editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy

GETTING THROUGH THE DEAL Initial Public Offerings Initial Public Offerings Public Initial Contributing editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy 2017 Law Business Research 2017 © Law Business Research 2016 Initial Public Offerings 2017 Contributing editors Joshua Ford Bonnie and Kevin P Kennedy Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP Publisher Law The information provided in this publication is Gideon Roberton general and may not apply in a specific situation. [email protected] Business Legal advice should always be sought before taking Research any legal action based on the information provided. Subscriptions This information is not intended to create, nor does Sophie Pallier Published by receipt of it constitute, a lawyer–client relationship. [email protected] Law Business Research Ltd The publishers and authors accept no responsibility 87 Lancaster Road for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although Senior business development managers London, W11 1QQ, UK the information provided is accurate as of July 2016, Alan Lee Tel: +44 20 3708 4199 be advised that this is a developing area. [email protected] Fax: +44 20 7229 6910 Adam Sargent © Law Business Research Ltd 2016 Printed and distributed by [email protected] No photocopying without a CLA licence. Encompass Print Solutions First published 2015 Tel: 0844 2480 112 Dan White Second edition [email protected] ISSN 2059-5484 © Law Business Research 2016 CONTENTS Global overview 5 Japan 51 Joshua Ford -

Does the Glass Ceiling Exist? a Longitudinal Study of Women's

The Journal of Applied Business Research – May/June 2014 Volume 30, Number 3 Does The Glass Ceiling Exist? A Longitudinal Study Of Women’s Progress On French Corporate Boards Rey Dang, La Rochelle Business School, France Duc Khuong Nguyen, IPAG Business School, France Linh-Chi Vo, EM Normandie, France ABSTRACT In this article, we conduct a longitudinal study of women’s progress on French corporate boards of directors. We particularly focus on the extent to which women directors have circumvented the glass ceiling. Using a sample of SBF 120 companies over a 10-year period from 2000 to 2009, our results provide evidence of a significant increase in the number of women on French corporate boards. However, the corporate glass ceiling hypothesis is consistently rejected whatever the considered measure of female directors; i.e., the number of board seats held by women, the number of firms with a critical mass of female directors, and the number of directorships held by each women director. Keywords: Boards of Directors; Gender; Diversity; Corporate Governance 1. INTRODUCTION ver the period 2000-2009, the average participation rate of women in the labor market increased from 60 to 64 percent across the European Union’s 27 Members States. More specifically, in France, it went up from 60.3 to 64.9 percent.1 However, despite this notable progress, women remain under-represented Oin senior or executive positions (ILO, 2009).2 This lack of female representation on corporate boards of directors, which is commonly referred to as glass ceiling in practice and past academic studies, seems to be a global phenomenon because women on corporate boards (WOCB) represents less than 15% of board members in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and many European countries (Dang & Vo, 2012).3 Morrison et al. -

Examining Drivers of Trading Volume in European Markets

Received: 28 July 2016 Accepted: 19 December 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ijfe.1608 RESEARCH ARTICLE Examining drivers of trading volume in European markets Bogdan Batrinca | Christian W. Hesse | Philip C. Treleaven Department of Computer Science, Abstract University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK This study presents an in‐depth exploration of market dynamics and analyses potential drivers of trading volume. The study considers established facts from Correspondence Bogdan Batrinca, Department of the literature, such as calendar anomalies, the correlation between volume and Computer Science, University College price change, and this relation's asymmetry, while proposing a variety of time London, Gower Street, London WC1E series models. The results identified some key volume predictors, such as the 6BT, UK. Email: [email protected] lagged time series volume data and historical price indicators (e.g. intraday range, intraday return, and overnight return). Moreover, the study provides empirical evi- Funding information dence for the price–volume relation asymmetry, finding an overall price asymme- Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) UK try in over 70% of the analysed stocks, which is observed in the form of a moderate overnight asymmetry and a more salient intraday asymmetry. We conclude that JEL Classification: C32; C52; C58; G12; volatility features, more recent data, and day‐of‐the‐week features, with a notable G15; G17 negative effect on Mondays and Fridays, improve the volume prediction model. KEYWORDS asymmetric models, behavioural finance, European stock market, feature selection, price volume relation, trading volume 1 | INTRODUCTION which was $63tn in 2011 (World Federation of Exchanges, 2012) and $49tn in 2012 (World Federation of Exchanges, This study investigates the drivers affecting the trading 2013). -

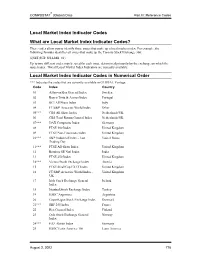

Local Market Index Indicator Codes in Numerical

® COMPUSTAT (Global) Data Part III: Reference Codes Local Market Index Indicator Codes What are Local Market Index Indicator Codes? These codes allow you to identify those issues that make up a local market index. For example, the following formula identifies all issues that make up the Toronto Stock Exchange 300: @SET($GI+$FI,LMII=81) Up to two different codes may be used for each issue, determined primarily by the exchange on which the issue trades. Not all Local Market Index Indicators are currently available. Local Market Index Indicator Codes in Numerical Order *** Indicates the codes that are currently available in GLOBAL Vantage Code Index Country 01 Affarsvarlden General Index Sweden 02 Banco Totta & Acores Index Portugal 03 BCI All Share Index Italy 04 FT/S&P Actuaries World Index Other 05*** CBS All Share Index Netherlands/UK 06 CBS Total Return General Index Netherlands/UK 07*** DAX Composite Index Germany 08 FTSE 100 Index United Kingdom 09 FTSE Non-Financials Index United Kingdom 10*** S&P Industrial Index - Last United States Trading Day 11*** FTSE All-Share Index United Kingdom 12 Bombay SE Natl Index India 13 FTSE 250 Index United Kingdom 14*** Vienna Stock Exchange Index Austria 15 FTSE SmallCap EX IT Index United Kingdom 16 FT/S&P Actuaries World Index - United Kingdom UK 17 Irish Stock Exchange General Ireland Index 18 Istanbul Stock Exchange Index Turkey 19 HSBC Argentina Argentina 20 Copenhagen Stock Exchange Index Denmark 21*** SBF 250 Index France 22 Hex General Index Finland 23 Oslo Stock Exchange General Norway -

Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics

Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics Diethelm Würtz Andrew Ellis Yohan Chalabi Rmetrics Association & Finance Online R/Rmetrics eBook Series R/Rmetrics eBooks is a series of electronic books and user guides aimed at students and practitioner who use R/Rmetrics to analyze financial markets. A Discussion of Time Series Objects for R in Finance (2009) Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2009 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz Basic R for Finance (2010), Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Longhow Lam, Andrew Ellis Chronological Objects with Rmetrics (2010), Diethelm Würtz, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis Portfolio Optimization with R/Rmetrics (2010), Diethelm Würtz, William Chen, Yohan Chalabi, Andrew Ellis Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm W?rtz, Andrew Ellis, Yohan Chalabi Indian Financial Market Data for R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm Würtz, Mahendra Mehta, Andrew Ellis, Yohan Chalabi Asian Option Pricing with R/Rmetrics (2010) Diethelm Würtz R/Rmetrics Singapore 2010 Proceedings of the Singapore Workshop 2010 Editors Diethelm Würtz, Mahendra Mehta, David Scott, Juri Hinz R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2011 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer School and Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz III tinn-R Editor (2010) José Cláudio Faria, Philippe Grosjean, Enio Galinkin Jelihovschi and Ri- cardo Pietrobon R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2011 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer Scholl and Workshop 2011 Editor Diethelm Würtz R/Rmetrics Meielisalp 2012 Proceedings of the Meielisalp Summer Scholl and Workshop 2012 Editor Diethelm Würtz Topics in Empirical Finance with R and Rmetrics (2013), Patrick Hénaff FINANCIAL MARKET DATA FOR R/RMETRICS DIETHELM WÜRTZ ANDREW ELLIS YOHAN CHALABI RMETRICS ASSOCIATION &FINANCE ONLINE Series Editors: Prof. -

UK FTSE 100 PDF Factsheet

FACTSHEET 31 August 2021 Life Fund Halifax UK FTSE 100 Halifax UK FTSE 100 single priced. This document is provided for the purpose of information only. This factsheet is intended for Asset Allocation (as at 30/06/2021) individuals who are familiar with investment UK Equity 98.8% terminology. Please contact your financial adviser if you need an explanation of the terms Money Market 1.1% used. This material should not be relied upon Futures 0.1% as sufficient information to support an investment decision. The portfolio data on this factsheet is updated on a quarterly basis. Fund Aim To match as closely as possible, subject to the effect of charges and regulations in force from time to time, the capital performance and net income yield of the FTSE 100 index. The Halifax FTSE 100 Index Tracking Life and Pension funds invest directly into the Halifax FTSE 100 Index Tracking OEIC. Derivatives Sector Breakdown (as at 30/06/2021) may be used for efficient portfolio management purposes only. Consumer Staples 18.4% Financials 17.8% Basic Fund Information Industrials 11.8% Fund Launch Date 29/02/1996 Basic Materials 11.1% Fund Size £10.1m Consumer Discretionary 10.7% Benchmark FTSE 100 Health Care 10.5% ISIN GB0031020992 Energy 9.0% MEX ID H9FTSP Other 4.9% SEDOL 3102099 Utilities 3.2% Manager Name Quantitative Investment Team Telecommunications 2.7% Manager Since 01/04/2005 Top Ten Holdings (as at 30/06/2021) Regional Breakdown (as at 30/06/2021) ASTRAZENECA PLC GBP0.0025 5.9% UNILEVER PLC GBP0.0311 5.7% HSBC HOLDINGS PLC GBP0.005 4.4% DIAGEO -

A Proposal for Regulatory Oversight of Stock Market Index Providers

Benchmarking the World: A Proposal for Regulatory Oversight of Stock Market Index Providers ABSTRACT Wall Street has recently seen a shift from active management, which involves investors or portfolio managers buying and selling stocks, towards passive management, where investors invest in funds that seek to match the returns of an underlying index. As the popularity of index funds has grown, questions have arisen regarding the role of the index providers that produce the underlying indices. Unlike the funds themselves, these providers are largely unregulated, and have considerable discretion to determine the makeup of indices. This wide discretion allows index providers to exercise control over the global investment community since they have the ability to control investors’ exposure to different countries’ markets. The role of index providers also raises concerns about investor transparency and market manipulation in the wake of the 2012 LIBOR manipulation scandal. Recently, efforts have been made to create regulatory frameworks within Europe and on an international scale. This Note argues that the US investment industry should require index providers to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission and to solicit comments from the public through notice-and-comment periods when the providers add new rules or modify existing rules. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1192 II. THE RISE OF PASSIVE INVESTING AND THE IMPORTANCE OF STOCK MARKET INDICES ........................................................ -

FTSE UK Index Series Family

Benchmark Statement FTSE UK Index Series Family September 2021 v1.6 FTSE Russell An LSEG Business | FTSE UK Index Series Family This benchmark statement is provided by FTSE International Limited as the administrator of the FTSE UK Index Series Family. It is intended to meet the requirements of EU Benchmark Regulation (EU2016/1011) and the supplementary regulatory technical standards and the retained EU law in the UK (The Benchmarks (Amendment and Transitional Provision) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019) that will take effect in the United Kingdom at the end of the EU Exit Transition Period on 31 December 2020. The benchmark statement should be read in conjunction with the FTSE UK Index Series Ground Rules and other associated policies and methodology documents. Those documents are italicised whenever referenced in this benchmark statement and are included as an appendix to this document. They are also available on the FTSE Russell website (www.ftserussell.com). References to “BMR” or “EU BMR” in this benchmark statement refer to Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on indices used as benchmarks in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds. References to “DR” in this benchmark statement refer to Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1643 of 13 July 2018 supplementing Reguorlation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards specifying further the contents of, and cases where updates are required to, the benchmark statement to be published by the administrator of a benchmark. -

Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2008 Q1

6 Quarterly Bulletin 2008 Q1 Markets and operations This article reviews developments in sterling financial markets since the 2007 Q4 Quarterly Bulletin up to the end of February 2008. The article also reviews the Bank’s official operations during this period. Sterling financial markets(1) Chart 1 Changes in UK equity indices since 2 January 2007 Overview FTSE 100 FTSE 250 There were some signs of improvement in sterling money FTSE All-Share FTSE Small Cap Indices: 2 Jan. 2007 = 100 markets in December and early January, including a more 110 Previous Bulletin orderly year-end period than many market participants had 105 feared. But during February, conditions deteriorated again. While banks were reportedly able to raise very short-term 100 funds — up to around one month — longer-maturity funding markets remained impaired. 95 90 Information from market prices and comments by market participants suggested that difficult conditions in bank term 85 funding markets would continue for some time, which would 80 be likely to lead to a reduction in the supply of credit to the 75 economy generally. This could act as a drag on economic Jan. Mar. May July Sep. Nov. Jan. activity, and in turn could prompt further deterioration in the 2007 08 quality of banks’ assets and limit their ability and willingness Sources: Bloomberg and Bank calculations. to lend. Perhaps consistent with perceptions of possible Chart 2 Selected sectoral UK equity indices(a) adverse feedback effects between banks’ balance sheets and the macroeconomy, UK equity markets fell quite sharply in Mining Banks Oil and gas Real estate January (and became more volatile). -

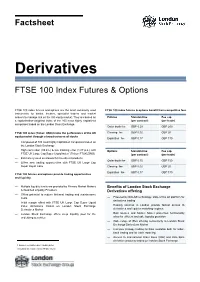

FTSE 100 Index Futures & Options

Factsheet Derivatives FTSE 100 Index Futures & Options FTSE 100 index futures and options are the most commonly used FTSE 100 index futures & options benefit from competitive fees instruments for banks, brokers, specialist traders and market makers to manage risk on the UK equity market. They are based on Futures Standard fee Fee cap a capitalization-weighted index of the 100 most highly capitalized (per contract) (per trade) companies traded on the London Stock Exchange. Order-book fee GBP 0.20 GBP 200 FTSE 100 index (Ticker: UKX) tracks the performance of the UK Clearing fee GBP 0.02 GBP 20 equity market through a broad universe of stocks Expiration fee GBP 0.17 GBP 170 — Composed of 100 most highly capitalized companies traded on the London Stock Exchange — High correlation (99.6%) & low tracking error (1.87 p.a.) with Options Standard fee Fee cap 1 FTSE UK Large Cap Super Liquid index (Ticker: FTUKLSNG) (per contract) (per trade) — Extensively used as a basis for investment products Order-book fee GBP 0.15 GBP 150 — Offers new trading opportunities with FTSE UK Large Cap Super Liquid index Clearing fee GBP 0.02 GBP 20 Expiration fee GBP 0.17 GBP 170 FTSE 100 futures and options provide trading opportunities and liquidity — Multiple liquidity levels are provided by Primary Market Makers Benefits of London Stock Exchange & Qualified Liquidity Providers Derivatives offering — Offers potential to reduce frictional trading and maintenance costs — Powered by SOLA® technology, state of the art platform for derivatives trading — Initial margin