Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2008 Q1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midwest Financial Brian Johnson, RFC 706 Montana Street Glidden, IA 51443 [email protected] 712-659-2156

Midwest Financial Brian Johnson, RFC 706 Montana Street Glidden, IA 51443 www.midwestfinancial.us [email protected] 712-659-2156 The SITREP for the week ending 08/06/2021 ***************************************************** SIT REP: n. a report on the current situation; a military abbreviation; from "situation report". In the markets: U.S. Markets: U.S. stocks recorded solid gains for the week and several indices hit record highs. The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 273 points finishing the week at 35,209, a gain of 0.8%. The NASDAQ retraced all of last week’s decline by rising 1.1% to close at 14,836. By market cap, the large cap S&P 500 rose 0.9%, while the mid cap S&P 400 and small cap Russell 2000 gained 0.5% and 1.0%, respectively. International Markets: Major international markets also finished the week solidly in the green. Canada’s TSX added 0.9%, while the United Kingdom’s FTSE 100 gained 1.3%. France’s CAC 40 and Germany’s DAX rose 3.1% and 1.4%, respectively. China’s Shanghai Composite added 1.8%, while Japan’s Nikkei rallied 2%. As grouped by Morgan Stanley Capital International, developed markets finished up 1.0% and emerging markets gained 0.7%. Commodities: Precious metals had a difficult week. Gold retreated -3.0% to $1763.10 per ounce, while Silver fell a steeper -4.8% to $24.33. West Texas Intermediate crude oil gave up all of the last two week’s gains, declining -7.7% to $68.28 per barrel. The industrial metal copper, viewed by some analysts as a barometer of world economic health due to its wide variety of uses, finished the week down -3%. -

Scanned Image

3130 W 57th St, Suite 105 Sioux Falls, SD 57108 Voice: 605-373-0201 Fax: 605-271-5721 [email protected] www.greatplainsfa.com Securities offered through First Heartland Capital, Inc. Member FINRA & SIPC. Advisory Services offered through First Heartland Consultants, Inc. Great Plains Financial Advisors, LLC is not affiliated with First Heartland Capital, Inc. In this month’s recap: the Federal Reserve eases, stocks reach historic peaks, and face-to-face U.S.-China trade talks formally resume. Monthly Economic Update Presented by Craig Heien with Great Plains Financial Advisors, August 2019 THE MONTH IN BRIEF July was a positive month for stocks and a notable month for news impacting the financial markets. The S&P 500 topped the 3,000 level for the first time. The Federal Reserve cut the country’s benchmark interest rate. Consumer confidence remained strong. Trade representatives from China and the U.S. once again sat down at the negotiating table, as new data showed China’s economy lagging. In Europe, Brexit advocate Boris Johnson was elected as the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and the European Central Bank indicated that it was open to using various options to stimulate economic activity.1 DOMESTIC ECONOMIC HEALTH On July 31, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates for the first time in more than a decade. The Federal Open Market Committee approved a quarter-point reduction to the federal funds rate by a vote of 8-2. Typically, the central bank eases borrowing costs when it senses the business cycle is slowing. As the country has gone ten years without a recession, some analysts viewed this rate cut as a preventative measure. -

FRC Board Diversity and Effectiveness in FTSE 350

Leadership Institute Board Diversity and Effectiveness in FTSE 350 Companies July 2021 Acknowledgements Report written by: Mary Akimoto, Osman Anwar, Molly Broome, Dragos Diac, Dr Randall S Peterson, Dr Sergei Plekhanov, Simon Osborne and Vyla Rollins We thank the following individuals on the joint LBSLI/SQW research team for their contributions to this research: • Ruth Cluness, LBSLI • Tom Gosling, LBSLI • Brent Hamerla, LBSLI • Letitia Joseph, LBSLI • Barbara Moorer, LBSLI • Andrei Visiteu, LBSLI • Desi Zlatanova, LBSLI We also give a special thank you to our team of research interviewers: • Eva Beazley • Helen Beedham • Christine de Largy • Kathryn Gordon • Dr JoEllyn Prouty McLaren The London Business School Leadership Institute expresses its thanks to all of our stakeholder and collaborators, who supported our research efforts. We would like to express our specific gratitude to the following individuals, for their invaluable guidance, comments, suggestions and support throughout this project: Kit Bingham, Charlie Brown, Gerry Brown, Sue Clark, Louis Cooper, John Dore, Lisa Duke, Roshy Dwyer, Farrer & Co (Anisha Birk, Natalie Rimmer, Peter Wienand), Louise Fowler, Dr Julian Franks, Dr Karl George MBE, Dr Tom Gosling, Dr Byron Grote, Fiona Hathorn, Jonathan Hayward, Susan Hooper, Dr Ioannis Ioannou, Bernhard Kerres, LBS Accounts department (Akposeba Mukoro, Janet Nippard), LBS Advancement department (Luke Ashby, Susie Balch, Nina Bohn, Ian Frith, Sarah Jeffs, Maria Menicou), LBS Executive Education, LBS Research & Faculty Office and -

UK FTSE 100 PDF Factsheet

FACTSHEET 31 August 2021 Life Fund Halifax UK FTSE 100 Halifax UK FTSE 100 single priced. This document is provided for the purpose of information only. This factsheet is intended for Asset Allocation (as at 30/06/2021) individuals who are familiar with investment UK Equity 98.8% terminology. Please contact your financial adviser if you need an explanation of the terms Money Market 1.1% used. This material should not be relied upon Futures 0.1% as sufficient information to support an investment decision. The portfolio data on this factsheet is updated on a quarterly basis. Fund Aim To match as closely as possible, subject to the effect of charges and regulations in force from time to time, the capital performance and net income yield of the FTSE 100 index. The Halifax FTSE 100 Index Tracking Life and Pension funds invest directly into the Halifax FTSE 100 Index Tracking OEIC. Derivatives Sector Breakdown (as at 30/06/2021) may be used for efficient portfolio management purposes only. Consumer Staples 18.4% Financials 17.8% Basic Fund Information Industrials 11.8% Fund Launch Date 29/02/1996 Basic Materials 11.1% Fund Size £10.1m Consumer Discretionary 10.7% Benchmark FTSE 100 Health Care 10.5% ISIN GB0031020992 Energy 9.0% MEX ID H9FTSP Other 4.9% SEDOL 3102099 Utilities 3.2% Manager Name Quantitative Investment Team Telecommunications 2.7% Manager Since 01/04/2005 Top Ten Holdings (as at 30/06/2021) Regional Breakdown (as at 30/06/2021) ASTRAZENECA PLC GBP0.0025 5.9% UNILEVER PLC GBP0.0311 5.7% HSBC HOLDINGS PLC GBP0.005 4.4% DIAGEO -

A Proposal for Regulatory Oversight of Stock Market Index Providers

Benchmarking the World: A Proposal for Regulatory Oversight of Stock Market Index Providers ABSTRACT Wall Street has recently seen a shift from active management, which involves investors or portfolio managers buying and selling stocks, towards passive management, where investors invest in funds that seek to match the returns of an underlying index. As the popularity of index funds has grown, questions have arisen regarding the role of the index providers that produce the underlying indices. Unlike the funds themselves, these providers are largely unregulated, and have considerable discretion to determine the makeup of indices. This wide discretion allows index providers to exercise control over the global investment community since they have the ability to control investors’ exposure to different countries’ markets. The role of index providers also raises concerns about investor transparency and market manipulation in the wake of the 2012 LIBOR manipulation scandal. Recently, efforts have been made to create regulatory frameworks within Europe and on an international scale. This Note argues that the US investment industry should require index providers to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission and to solicit comments from the public through notice-and-comment periods when the providers add new rules or modify existing rules. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1192 II. THE RISE OF PASSIVE INVESTING AND THE IMPORTANCE OF STOCK MARKET INDICES ........................................................ -

FTSE UK Index Series Family

Benchmark Statement FTSE UK Index Series Family September 2021 v1.6 FTSE Russell An LSEG Business | FTSE UK Index Series Family This benchmark statement is provided by FTSE International Limited as the administrator of the FTSE UK Index Series Family. It is intended to meet the requirements of EU Benchmark Regulation (EU2016/1011) and the supplementary regulatory technical standards and the retained EU law in the UK (The Benchmarks (Amendment and Transitional Provision) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019) that will take effect in the United Kingdom at the end of the EU Exit Transition Period on 31 December 2020. The benchmark statement should be read in conjunction with the FTSE UK Index Series Ground Rules and other associated policies and methodology documents. Those documents are italicised whenever referenced in this benchmark statement and are included as an appendix to this document. They are also available on the FTSE Russell website (www.ftserussell.com). References to “BMR” or “EU BMR” in this benchmark statement refer to Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on indices used as benchmarks in financial instruments and financial contracts or to measure the performance of investment funds. References to “DR” in this benchmark statement refer to Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1643 of 13 July 2018 supplementing Reguorlation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to regulatory technical standards specifying further the contents of, and cases where updates are required to, the benchmark statement to be published by the administrator of a benchmark. -

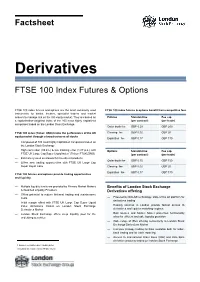

FTSE 100 Index Futures & Options

Factsheet Derivatives FTSE 100 Index Futures & Options FTSE 100 index futures and options are the most commonly used FTSE 100 index futures & options benefit from competitive fees instruments for banks, brokers, specialist traders and market makers to manage risk on the UK equity market. They are based on Futures Standard fee Fee cap a capitalization-weighted index of the 100 most highly capitalized (per contract) (per trade) companies traded on the London Stock Exchange. Order-book fee GBP 0.20 GBP 200 FTSE 100 index (Ticker: UKX) tracks the performance of the UK Clearing fee GBP 0.02 GBP 20 equity market through a broad universe of stocks Expiration fee GBP 0.17 GBP 170 — Composed of 100 most highly capitalized companies traded on the London Stock Exchange — High correlation (99.6%) & low tracking error (1.87 p.a.) with Options Standard fee Fee cap 1 FTSE UK Large Cap Super Liquid index (Ticker: FTUKLSNG) (per contract) (per trade) — Extensively used as a basis for investment products Order-book fee GBP 0.15 GBP 150 — Offers new trading opportunities with FTSE UK Large Cap Super Liquid index Clearing fee GBP 0.02 GBP 20 Expiration fee GBP 0.17 GBP 170 FTSE 100 futures and options provide trading opportunities and liquidity — Multiple liquidity levels are provided by Primary Market Makers Benefits of London Stock Exchange & Qualified Liquidity Providers Derivatives offering — Offers potential to reduce frictional trading and maintenance costs — Powered by SOLA® technology, state of the art platform for derivatives trading — Initial margin -

Amir Receives a Warm Welcome

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, MARCH 15, 2014 JAMADA ALAWWAL 14, 1435 AH No: 16105 Lebanese President Suleiman optimistic 4 150 Fils Amir receives a Egyptian fugitive a warm welcome teacher in Kuwait? Mystery surrounds Qabouti’s visa KUWAIT: An alleged Muslim Brotherhood mem- Jarida daily said that Qabouti entered Kuwait ber arrested in Kuwait recently has been living in with a ‘commercial visit visa’ issued by a private the Gulf state since October last year, and was in school “which matches his occupation as a the process of obtaining a work visa as a teacher, teacher (as stated in his passport)”. “The school according to security sources. The Egyptian recently launched preparations to transfer his national, Mohammed El-Qabouti was reportedly visa to a work permit after renewing it more than detained in Mangaf last week after local authori- five times,” said security sources quoted in the ties received information from the Interpol of his report. whereabouts and an arrest warrant issued in his The man was able to enter Kuwait without home country. problems until he was listed as a fugitive a week The circumstances behind his arrival in before his arrest based on the Interpol’s letter. Kuwait remain a mystery, but sources quoted by “Qabouti remains in Kuwait authority’s custody Al-Qabas daily yesterday hinted that he had as he awaits Egyptian security operatives who entered legally with a visa issued with help of an will take him to Egypt,” the sources added. official in the Islamic Constitutional Movement - Meanwhile, Al-Rai daily reported that the man the Muslim Brotherhood’s tacit political arm in was not likely to be a senior Muslim Brotherhood Kuwait. -

The Merchants Trust

The Merchants Trust Benefits from announced debt refinancing Investment trusts 3 November 2017 The Merchants Trust (MRCH) adopts a long-term approach to investing in UK equities, aiming to generate an above-average level of income along Price 490.0p with long-term capital and income growth. The trust has announced a Market cap £533m refinancing of its first tranche of high-cost debt, which will bring its AUM £692m effective cost of borrowing down from 8.5% to 6.1%, saving £2.8m in annual interest costs and locking in low-cost funding for the next 35 years. NAV* 507.6p Discount to NAV 3.5% The board adopts a progressive dividend policy; annual dividends have NAV** 517.6p increased for the last 35 consecutive years and the current 5.0% yield Discount to NAV 5.3% compares favourably with the average of MRCH’s peers in the AIC UK *Excluding income. **Including income. As at 1 November. Equity Income sector. Yield 5.0% Ordinary shares in issue 108.7m 12 months Share price NAV* Blended FTSE All-Share FTSE 100 Code MRCH ending (%) (%) benchmark** (%) (%) (%) Primary exchange LSE 31/10/13 45.2 36.0 20.7 22.8 20.7 AIC sector UK Equity Income 31/10/14 (3.1) (2.6) 0.7 1.0 0.7 Benchmark FTSE All-Share 31/10/15 (2.0) 2.6 0.8 3.0 0.8 31/10/16 1.1 9.3 13.7 12.2 13.7 Share price/discount performance 31/10/17 21.5 15.5 13.2 13.4 12.1 500 0 Source: Thomson Datastream. -

FTSE 350 Climate Change Report 2013

01 Are UK companies prepared for the international impacts of climate change? FTSE 350 Climate Change Report 2013 9 October 2013 Report writer and global advisor 02 03 The evolution of CDP Contents With great pleasure, CDP announced an exciting change this year. CEO Foreword 4 Executive Summary 6 Over ten years ago CDP pioneered the only global disclosure system for companies to report their environmental impacts and strategies to investors. In that time, 2013 Climate Performance and Disclosure Leaders 8 and with your support, CDP has accelerated climate change and natural resource 2013 Leadership Criteria 10 issues to the boardroom and has moved beyond the corporate world to engage Investor insight - the “Aiming for A” coalition 11 with cities and governments. FTSE 350 companies have a global footprint 12 The CDP platform has evolved significantly, supporting multinational purchasers Companies’ focus on climate change risks and opportunities needs broadening 12 to build more sustainable supply chains. It enables cities around the world to exchange information, take best practice action and build climate resilience. We Scientific Insight - Professor Sir Brian Hoskins 17 assess the climate performance of companies and drive improvements through Companies’ understanding of their value chain is limited 20 shareholder engagement. Corporate insight - Reckitt Benckiser 22 Our offering to the global marketplace has expanded to cover a wider spectrum of FTSE 100 companies have a more sophisticated response the earth’s natural capital, specifically water and forests, alongside carbon, energy to climate change than FTSE 250 companies 23 and climate. Preparing for climate change: Comparing FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 companies 26 For these reasons, we have outgrown our former name of the Carbon Disclosure PwC commentary – Celine Herweijer 28 Project and rebranded to CDP. -

International Football Results Lead to Irrationality in the German Stock Market?

International football results lead to irrationality in the German stock market? ERASMUS UNIVERSITY ROTTERDAM ERASMUS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Bachelor Thesis Financial Economics Hamid Samadi 416255 Supervisor: Dr. Jing Zhao Date final thesis: 23-08-2017 Abstract This study intends to find a possible relationship between the football match outcomes of the German national team and the German stock market. This will be done by using daily data from the DAX index in the period of 1 June 1990 to 15 July 2016. During this period, all matches played by the German national team in the World Cup and the Euro Cup will be taken into investigation. The method that is applied to test for a possible relationship between the index returns and the match outcomes is an Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) statistical regression model. After conducting the research with the statistical model, no statistical significant relationship was found between the index returns and the match outcomes. This finding indicates that the German stock market is unaffected by the outcomes of the football matches in major football events. This conclusion is not in line with the findings of major studies in this field, examples are studies of Ashton, Gerard and Hudson (2003) and Edmans, Garcia and Norli (2007), in both which there was documented a significant relationship between football results and particular stock markets. Table of contents Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 -

Vanguard FTSE International Index Funds Annual

Annual Report | October 31, 2020 Vanguard FTSE International Index Funds Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Index Fund Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small-Cap Index Fund See the inside front cover for important information about access to your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports. Important information about access to shareholder reports Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of your fund’s annual and semiannual shareholder reports will no longer be sent to you by mail, unless you specifically request them. Instead, you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted on the website and will be provided with a link to access the report. If you have already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and do not need to take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the fund electronically by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker-dealer or bank) or, if you invest directly with the fund, by calling Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or by logging on to vanguard.com. You may elect to receive paper copies of all future shareholder reports free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact the intermediary to request that you continue to receive paper copies. If you invest directly with the fund, you can call Vanguard at one of the phone numbers on the back cover of this report or log on to vanguard.com.