(Re)Visioning Winnipeg's Chinatown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing a Complete Streets Checklist for Downtown Historic Districts and Character Neighbourhoods

Framing a Complete Streets Checklist for Downtown Historic Districts and Character Neighbourhoods: A Case Study of the Warehouse District, Winnipeg, Manitoba. by Pawanpreet Gill A Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF CITY PLANNING Department of City Planning University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 by Pawanpreet Gill Abstract This Major Degree Project explores the concept of “complete streets” and the framing of an appropriate “complete streets” checklist for historic districts and character neighbourhoods in downtown contexts, attempting to learn especially from the case of Winnipeg’s Warehouse District Neighbourhood. A “complete streets” checklist is considered to include a combination of infrastructure and urban design considerations, such as sidewalks, bike lanes, intersections, transit stops, curb extensions, travel lane widths, and parking needs. It proceeds from the premise that if an individual street or system of streets is ‘complete’, individuals will be more likely to reduce the time spent using automobiles, and increase the time expended on walking, biking, or using other transit alternatives, while making travel on the streets safer and more enjoyable for all users. The MDP examines the current street-related infrastructure and uses within the Warehouse District Neighbourhood of Downtown Winnipeg and discusses the relevance of current or recent City of Winnipeg plans and proposals. Taking the form of a practicum, the research sought to inform and engage local planners, engineers and public officials regarding a “complete streets” approach to their work – primarily in terms of the recommended framing of a complete streets checklist as well as recommendations for future area improvements in the Warehouse District Neighbourhood, demonstrating the usefulness of the checklist. -

Final Report DE Comments

Final Report July 24, 2013 BIKE TO WORK DAY FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2013 FINAL REPORT Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 1 Final Report July 24, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................. page 2 a. Event Background 2 b. 2013 Highlights 4 2. Planning Process......................................... page 5 a. Steering Committee 5 b. Event Coordinator Hours 7 c. Volunteers 8 d. Planning Recommendations 8 3. Events............................................................ page 9 a. Countdown Events 9 b. Pit Stops 12 c. BBQ 15 d. Event Recommendations 17 4. Sponsorship................................................... page 18 a. Financial Sponsorship 18 b. In Kind Sponsorship 20 c. Prizes 23 d. Sponsorship Recommendations 24 5. Budget........................................................... page 25 6. Media & Promotions..................................... page 27 a. Media Conference 27 b. Website-biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 28 c. Enewsletter 28 d. Facebook 28 e. Twitter 29 f. Print & Digital Media 29 g. Media Recommendations 29 7. Design............................................................ page 31 a. Logo 31 b. Posters 31 c. T-shirts 32 d. Banners 32 e. Free Press Ad 33 f. Bus Boards 33 g. Handbills 34 h. Design Recommendations 34 8. T-shirts............................................................ page 35 a. T-shirt Recommendations 36 9. Cycling Counts............................................. page 37 10. Feedback & Recommendations............... page 41 11. Supporting Documents.............................. page 43 a. Critical Path 43 b. Media Release 48 c. Sample Sponsorship Package 50 d. Volunteer List 55 Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 2 Final Report July 24, 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Winnipeg’s 6th Annual Bike to Work Day was held on Friday, June 21st, 2013. The event consisted of countdown events from June 17-21st, online registration, morning pit stops and an after work BBQ with free food and live music. -

Point Douglas (“The North End”) a Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and Their Children

Point Douglas (“The North End”) A Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and their Children North Point Douglas Point Lord Selkirk Park Dufferin Douglas William Whyte Burrows Central St. Johns Neighbourhoods Luxton Inkster-Faraday Robertson Mynarski South Point Douglas This guide is produced and maintained by the WRHA Point Douglas Community Health Office. For editing, revisions or other information regarding content, please contact Vince Sansregret @ 204-(801-7803) or email: [email protected] INDEX Community Leisure and Recreation Centres Page 2 City of Winnipeg Fee Subsidy Program Page 3 Public Computer Access sites Page 3 Licensed Child Care Facilities Page 4-5 Food Banks/Free Community Meal programs Page 6 Cooking Programs – Food Security Page 7 Discount Clothing, Furniture, Household items Page 8 Community Support Programs Page 9-11 Programs for Expecting Parents and Families with infants Page 12 Libraries / Family Literacy Page 13 Parent and Child/Parenting Support Programs Page 14-15 City of Winnipeg Priceless Fun FREE Programming Page 16 FREE Child/Youth Recreation/‘drop-in’ Programs Page 17-19 Adult Ed.-Career Preparation Programs Page 20-21 Community, Leisure and Recreation Centres Luxton Community Centre 210 St. Cross St. Win Gardner-North End Wellness Phone: 204- 582-8249 Center - YMCA 363 McGregor St. Norquay Community Centre Phone: 204-293-3910 65 Granville St. Phone: 204-943-6897 Turtle Island Neighbourhood Centre 510 King St Sinclair Park Community Phone: 204-986-8346 Centre 490 Sinclair Ave. William Whyte Neighbourhood Phone: 204-582-8257 Association – Pritchard Park Recreation Centre Ralph Brown Community 295 Pritchard Ave. Centre Phone: 204-582 – 0988 460 Andrews Street Phone: 204-586-3149 Sgt. -

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: a Canadian Inner-City Case

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: A Canadian Inner-City Case Rick Hesch winnipeg, manitoba This case study of an inner-city teacher education program documents the tensions at work on a social reconstructionist academic staff attempting to produce a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cultural relevance here includes three features: supporting academic achievement, maintaining cultural competence, and developing critical consciousness. All interests converge on the need to produce academically and technically competent teachers. Beyond this, the staff remain mindful of the dominant social and educational context within which they work and at the same time attempt to meet the longer-term interests of their students and culturally different inner-city communities. The possibilities for success have lessened in the political economy of the 1990s, but the study provides concrete instances of developing a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cette étude de cas portant sur un programme de formation à l’enseignement dans des écoles de quartiers défavorisés décrit les tensions au sein du personnel enseignant cher- chant à produire un programme de formation des maîtres culturellement significatif. Trois éléments définissent la pertinence culturelle d’un programme : il doit promouvoir la réussite scolaire, être adapté à la culture et développer une pensée critique. Tous les intervenants s’accordent sur la nécessité de produire des enseignants compétents. Cela dit, le personnel doit garder à l’esprit le contexte éducatif et social dominant dans lequel il travaille tout en essayant de tenir compte des intérêts à long terme des élèves et de diverses communautés culturelles implantées dans des quartiers défavorisés. L’étude fournit des exemples concrets de la marche à suivre pour élaborer un programme de formation à l’enseignement culturellement significatif. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

The Forks the Forks East Exchange District West

Rover Dike Isabel St. Princess St.King St. Red River Red River 26 16 N College Campus Main St. 30 8 EAST Whittier Park 15 22 24 12 EXCHANGE Notre Dame Ave. 18 DISTRICT 10 4 Homestead Park 13 1 23 11 7 19 3 Cumberland Ave. 31 WEST THEATRE Lagimodiére-Gaboury Park 2 EXCHANGE 5 DISTRICT Central DISTRICT Stephen Park Ellen St. Balmoral St. Balmoral Juba Park 6 Shaw Park Parc Elzéar Stadium Goulet P Pioneer Ave. Seine River William Stephenson Way Parkway Ellice Ave. 17 Parc Joseph 20 Colony St. Royal MTS PORTAGE AVE.CentrCentree Provencher 33 Canadian Museum Park of Human Rights University of 21 Winnipeg SHED Tache 25 HARGRAVE ST. Smith St. Main St. Promenade 28 Donald St. 32 THE Winnipeg FORKS Art Gallery Saint-Boniface Cathedral Memorial Blvd. Université de Osborne St. Osborne 9 Saint-Boniface 14 Broadway 29 Trans-Canada Hwy. Verendrye Park Manitoba South Point Legislative Park Building McFayden er Saint-Boniface Playground iv e R General Hospital oin inib Ass 4. Blüfish 14. Espresso Junction 24. Peasant Cookery enjoy the // 179 Bannatyne Avenue // 115-25 Forks Market Road // 283 Bannatyne Avenue Blüfish is a popular Japanese Located in the Johnston Terminal at This hip restaurant in the West bright lights of restaurant with excellently reviewed The Forks, Espresso Junction is a Exchange is a bustling place with food and a bright welcoming interior. quaint coffee shop serving their own hearty fresh dishes that keep patrons the big city blufish.ca in-house roasted coffee beans. returning time and time again. espressojunction.com peasantcookery.com ACCESS RESTAURANTS, CAFÉS 5. -

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

WINNIPEG DOWNTOWN PROFILE A Special Report on Demographic and Housing Market Factors in Winnipeg’s Downtown IUS SPECIAL REPORT JULY-2017 Institute of Urban Studies 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg P: 204 982-1140 F: 204 943-4695 E: [email protected] Mailing Address: 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 Author: Scott McCullough, Jino Distasio, Ryan Shirtliffe Data & GIS: Ryan Shirtliffe Research: Ryan Shirtliffe, Scott McCullough Supporting Research: Brad Muller, CentreVenture The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. Introduction This study undertakes an analysis of demographic and housing market factors that may influence the need for incentives in the downtown Winnipeg housing market. This report informs CentreVenture’s proposed “10 Year Housing Evaluation” and helps to address the proposed question, “What price do new downtown housing projects need to achieve to encourage more people to move downtown?” To accomplish this, the following have been undertaken: 1. A Demographic Analysis of current downtown Winnipeg residents with a comparison to Winnipeg medians, 2. A Rental Market Analysis comparing downtown rates to Winnipeg averages, as well as changing rental rates in the downtown from Census data, 3. -

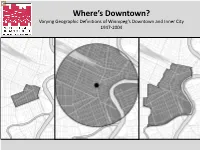

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization: CentreVenture’s Involvement in the Redevelopment of Downtown Winnipeg by Elisabeth Saftiuk A practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of City Planning Department of City Planning University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 Elisabeth Saftiuk Abstract Downtowns contribute significantly to the economy of cities and as a result, decision makers are increasingly recognizing the fundamental value and importance of maintaining viable downtown cores. Following the post-war era of urban decay and suburban expansion, there have been widespread attempts nationwide to reverse trends and to revitalize downtowns. In the Winnipeg context, urban renewal was practiced throughout the 1960s and 1970s; tripartite agreements were utilized during the 1980s; and development corporations were introduced throughout the 1980s and 1990s as a way to encourage private sector investment with targeted public sector investments. This practicum investigates the relationship between planning and development in the downtown revitalization context. In particular, this research aims to discover the extent to which a downtown development agency may have facilitated the better integration of planning and development in a city’s downtown, where revitalization has been very much on the public agenda. Winnipeg’s CentreVenture Development Corporation was used as a case study to explore this relationship. It was established in 1999 and continues to operate today. This paper attempts to determine the extent of its involvement, and the manner by which this arms-length government agency has aided and influenced tangible development in Winnipeg’s downtown. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 the Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (Pages 12-43 from Highlights from the Winnipeg Foundation’S 2020 Year)

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 The Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (pages 12-43 from Highlights from The Winnipeg Foundation’s 2020 year) Note: If you’d like to search this document for a specific fund, please follow these instructions: 1. Press Ctrl+F OR click on the magnifying glass icon (). 2. Enter all or a portion of the fund name. 3. Click Next. ENDOWMENT FUNDS 1921 - 2020 Celebrating the generous donors who give through The Winnipeg Foundation As we start our centennial year we want to sincerely thank and acknowledge the decades of donors from all walks of life who have invested in our community through The Winnipeg Foundation. It is only because of their foresight, commitment, and love of community that we can pursue our vision of “a Winnipeg where community life flourishes for all.” The pages ahead contain a list of endowment funds created at The Winnipeg Foundation since we began back in 1921. The list is organized alphabetically, with some sub-fund listings combined with the main funds they are connected to. We’ve made every effort to ensure the list is accurate and complete as of fiscal year-end 2020 (Sept. 30, 2020). Please advise The Foundation of any errors or omissions. Thank you to all our donors who generously support our community by creating endowed funds, supporting these funds through gifts, and to those who have remembered The Foundation in their estate plans. For Good. Forever. Mr. W.F. Alloway - Founder’s First Gift Maurice Louis Achet Fund The Widow’s Mite Robert and Agnes Ackland Memorial Fund Mr.