Winnipeg Downtown Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: a Canadian Inner-City Case

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: A Canadian Inner-City Case Rick Hesch winnipeg, manitoba This case study of an inner-city teacher education program documents the tensions at work on a social reconstructionist academic staff attempting to produce a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cultural relevance here includes three features: supporting academic achievement, maintaining cultural competence, and developing critical consciousness. All interests converge on the need to produce academically and technically competent teachers. Beyond this, the staff remain mindful of the dominant social and educational context within which they work and at the same time attempt to meet the longer-term interests of their students and culturally different inner-city communities. The possibilities for success have lessened in the political economy of the 1990s, but the study provides concrete instances of developing a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cette étude de cas portant sur un programme de formation à l’enseignement dans des écoles de quartiers défavorisés décrit les tensions au sein du personnel enseignant cher- chant à produire un programme de formation des maîtres culturellement significatif. Trois éléments définissent la pertinence culturelle d’un programme : il doit promouvoir la réussite scolaire, être adapté à la culture et développer une pensée critique. Tous les intervenants s’accordent sur la nécessité de produire des enseignants compétents. Cela dit, le personnel doit garder à l’esprit le contexte éducatif et social dominant dans lequel il travaille tout en essayant de tenir compte des intérêts à long terme des élèves et de diverses communautés culturelles implantées dans des quartiers défavorisés. L’étude fournit des exemples concrets de la marche à suivre pour élaborer un programme de formation à l’enseignement culturellement significatif. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

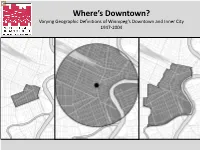

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Manitoba Rainbow Directory

Manitoba Rainbow Directory Welcome to the Manitoba Rainbow Directory, an up-to-date, comprehensive LGBT2SQ+ directory of organizations, businesses, services and individuals in Manitoba. There is no cost to be listed in the directory, which is intended to facilitate outreach, fundraising and marketing within the Manitoba LGBT2SQ+ community. If you would like to be added to the directory, could you please send your contact information to [email protected]. Please use the template below. Name of Individual/Business/Organization: Description (one line): Address: Name(s) and position: Phone: Email address: Website: Where you would like to be listed in the directory Listings in the Directory are in the following format: Community Organizations Education Individuals Organizations Health Counselling and Therapy Groups and Organizations Hospitality Cafes and Restaurants Hotels Organizations Retail Businesses Adult Products Other businesses Service providers Entertainment Home Renovations Legal Marriage Commissioners Massage Realtors Training Web design and Publishing Other services Social Activities: Culture, Entertainment, Recreation, and Sports Spiritual Affirming Ministries of the United Church of Canada Other Congregations Unaffiliated Individuals United Way Winnipeg Community Organizations Team-building fun, inspiration-sparking experiences, pulling together for a better Manitoba LGBT* Chamber of Commerce Winnipeg. 100% of your donation stays in The Manitoba LGBT* Chamber of Commerce exists Winnipeg. to help build a strong Manitoba economy 580 Main Street supported by, and supportive of, diverse Joanne Patenaude – Senior Manager New Business communities. Our mission is to cultivate, Development contribute to and promote a thriving community of (204)924-4232 LGBT* owned and allied businesses, professionals [email protected] and business students in Manitoba. -

River @ Osborne Osborne St

Context Map World Health Organization’s Eight Initiatives for Age-Friendly Cities 80000.00 0.90 70000.00 0.80 1) Outdoor spaces and built environment INTRODUCTION 60000.00 0.70 0.60 50000.00 2) Community support and health services 0.50 40000.00 0.40 30000.00 3) Transportation 0.30 Employment Rate 20000.00 0.20 Income 10000.00 0.10 4) Housing 0.00 0.00 80000.00 0.90 70000.00 0.80 Roslyn 5) Social participation 60000.00 0.70 McMillan 0.60 50000.00 River-‐Osborne 0.50 40000.00 6) Respect and inclusion 0.40 30000.00 0.30 Employment Rate 7) Civic participation and employment20000.00 0.20 Income 10000.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 8) Communication and information Roslyn McMillan This chart shows a unique Osborne Village is a rare urban environment structure that focuses on the aboveRiver-‐Osborne eight with a variety of local shops and businesses, key features that are fundamental in demographic situation historic homes and acclaimed restaurants. developing age-friendly cities, because all in Osborne Village. The It is identified as the City of Winnipeg’s people should be able to participate in the Roslyn area has the lowest Complete Communities as a Mixed Use urban environment, including those with employment rate but the highest Corridor. disabilities and the aged. income. Paired with the age characteristics, this shows that The Village is one of the highest density This presentation focuses on Osborne many retired older adults live in urban neighbourhoods in Western Canada Village through an age-friendly framework, the Roslyn area, whereas many with approximately 9,700 people per square noting the positives and negatives of the students and younger adults live kilometre. -

Winnipeg Heritage Conservation Districts

Winnipeg Heritage Conservation Districts PHASE 2: Case Study - Armstrong's Point May 2014 In Association With: SPAR Planning Services Historyworks Winnipeg Heritage Conservation Districts PHASE 2: Case Study - Armstrong's Point Prepared For: City of Winnipeg Urban Design Division Planning, Property & Development Department 15-30 Fort Street Winnipeg, MB R3C 4X5 Prepared By: HTFC Planning & Design 500 – 115 Bannatyne Avenue East Winnipeg, MB R3B OR3 In Association With: SPAR Planning Services Historyworks May, 2014 Acknowledgements Technical Experts Committee Neil Einarson Manager, Heritage Building Conservation Services, Manitoba Tourism, Culture, Heritage, Sport and Consumer Protection Cindy Tugwell Executive Director, Heritage Winnipeg Michael Robinson Senior Planner, Planning & Land Use Division, City of Winnipeg Martin Grady Zoning Administrator, Development & Inspections Division, City of Winnipeg Rick Derksen Building Plan Examination Architect, Plan Examination Branch, City of Winnipeg Armstrong’s Point neighbourhood property owners City of Winnipeg Staff, Urban Design Division Thank you to the volunteers who assisted in this process. TABLE OF CONTENTS PHASE 2: Case Study - Armstrong's Point 1.0 Introduction 03 2.0 Armstrong’s Point Neighbourhood as a Case Study 04 Determining Historic Significance & Integrity 05 Identification fo Natural & Built Historic Resources 05 Statement of Significance 08 Heritage Conservation District Boundaries 10 3.0 Community Engagement 10 Community Consultation Process 10 Workshop #1 11 Workshop #2 -

April 2019 Availability Report

APRIL 2019 AVAILABILITY REPORT INDUSTRIAL OFFICE RETAIL LAND & INVESTMENT FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE www.cwstevenson.ca Independently Owned and Operated / A Member of the Cushman & Wakefield Alliance ©2018 Cushman & Wakefield. All rights reserved. The information contained in this communication is strictly confidential. This information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been verified. NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE CONDITION OF THE PROPERTY (OR PROPERTIES) REFERENCED HEREIN OR AS TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO ERRORS, OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITIONS, WITHDRAWAL WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY SPECIAL LISTING CONDITIONS IMPOSED BY THE PROPERTY OWNER(S). ANY PROJECTIONS, OPINIONS OR ESTIMATES ARE SUBJECT TO UNCERTAINTY AND DO NOT SIGNIFY CURRENT OR FUTURE PROPERTY PERFORMANCE. INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE www.cwstevenson.ca CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE APRIL 2019 *Please click the property image for more details. CAM RENTAL & CONTACT ADDRESS ZONING UNIT/SUITE AREA AVAILABLE LOADING MAX CLR HT RATE TAX COMMENTS (SF +/-) GRADE DOCK (+/-) (PSF) (PSF) 26 BUNTING STREET TYSON PREISENTANZ M2 8,283 1 3 16' $7.50 $3.00 • Located in the heart of Inkster Industrial 204 928 5002 Park close to major trucking routes and many amenities • (+/-) 1,000 sf office build out • Great parking BROOKSIDE LOT 4 CHRIS MACSYMIC I2 6,750 - 39,875 24’ TBD TBD NEW STATE OF THE ART 204 928 5019 INDUSTRIAL BUILDING • Strategically located within CentrePort Canada TYSON PREISENTANZ • No city of Winnipeg business taxes 204 928 5002 • Direct access to CentrePort Canada Way and Route 90 in close proximity to the Winnipeg RYAN MUNT James A. -

Divided Prairie City Summary

summary the divided prairie city Income Inequality Among Winnipeg’s Neighbourhoods, 1970–2010 Edited by Jino Distasio and Andrew Kaufman Tom Carter, Robert Galston, Sarah Leeson-Klym, Christopher Leo, Brian Lorch, Mike Maunder, Evelyn Peters, Brendan Reimer, Martin Sandhurst, and Gina Sylvestre. This handout summarizes findings from The Divided Prairie City released by the Institute of Urban Studies Incomes are growing less (IUS) at The University of Winnipeg. 4 equal in Winnipeg. The IUS is part of a Neighbourhood Change Research Partner- ship (NCRP) funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities From 1970 to 2010, income inequality in Winnipeg grew by 20%. Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Led by the Cities Cen- • 40% of Winnipeg’s neighbourhoods experienced declining tre at the University of Toronto, this study examines income incomes from 1980 to 2010—only 16% of Winnipeg’s neigh- inequality in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Hamilton, Winnipeg, bourhoods experienced increasing incomes. Calgary, and Vancouver. • Income inequality has not grown in Winnipeg to the same extent that it has in Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver. Instead, Winnipeg resembles cities like Edmonton and Halifax because Income inequality is of lower concentrations of ultra high-income individuals. growing in Canada. Middle-income neighbour- 1 hoods are disappearing. Canadians believe that we live in a middle-class country, yet research 5 points to a growing income gap bet ween rich and poor neighbour- • From 1980 to 2010, one quarter of Winnipeg’s middle and up- hoods while the middle-income group shrinks. per middle-income neighbourhoods saw incomes decline to below average amounts. Incomes grew in only 13% of mid- Fourteen per cent of all income in Canada is now received by dle-income areas to above-average levels. -

2020 Downtown Snapshot Our Misson

2020 DOWNTOWN SNAPSHOT OUR MISSON Covid-19 has posed a challenge We promote, care and to local businesses like no other. But our community is resilient, advocate for a vibrant and and the Downtown Winnipeg BIZ is working to help downtown inclusive downtown where businesses come back stronger than ever before. business thrives and people Despite an incredibly challenging year, the future of downtown are drawn to work, live, remains bright. This snapshot offers a high-level view of our downtown right now – shop and explore. and reasons to feel more optimistic than ever about where we’re going. WORK Where do we work downtown? The top five employment fields in downtown Winnipeg: Health care and social assistance 14% Accommodation and food services 11% Retail trade 10% Professional, scientific and technical services 8% Manufacturing 8% DOWNTOWN WINNIPEG BIZ 2020 DOWNTOWN SNAPSHOT 3 “ The downtown community is incredible. Downtown Winnipeg is both charming and safe, WORK and the people who live, work and visit downtown are super friendly. We’re a new business and there’s no place we’d rather be.” Lily Zhao –POKÉ MONO DID YOU KNOW? • Over 70,000 Winnipeggers work downtown. • Our downtown makes up just 3.5% of Winnipeg by area, but nearly 40% of Winnipeg’s top employers are located downtown. • Despite an incredibly challenging year, 19 new businesses opened their doors in downtown Winnipeg in 2020. DOWNTOWN WINNIPEG BIZ 2020 DOWNTOWN SNAPSHOT 4 WORK “ Thousands of hungry workers, ample foot traffic and easy loading for vehicles – the decision to open downtown was a no-brainer. -

Volume 3: Population Groups and Ethnic Origins

Ethnicity SEriES A Demographic Portrait of Manitoba Volume 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins Sources: Statistics Canada. 2001 and 2006 Censuses – 20% Sample Data Publication developed by: Statistics Canada information is used with the permission of Statistics Canada. Manitoba Immigration and Users are forbidden to copy the data and redisseminate them, in an original or Multiculturalism modified form, for commercial purposes, without permission from Statistics And supported by: Canada. Information on the availability of the wide range of data from Statistics Canada can be obtained from Statistics Canada’s Regional Offices, its World Wide Citizenship and Immigration Canada Web site at www.statcan.gc.ca, and its toll-free access number 1-800-263-1136. Contents Introduction 2 Canada’s Population Groups 3 manitoba’s Population Groups 4 ethnic origins 5 manitoba Regions 8 Central Region 10 Eastern Region 13 Interlake Region 16 Norman Region 19 Parklands Region 22 Western Region 25 Winnipeg Region 28 Winnipeg Community Areas 32 Assiniboine South 34 Downtown 36 Fort Garry 38 Inkster 40 Point Douglas 42 River East 44 River Heights 46 Seven Oaks 48 St. Boniface 50 St. James 52 St. Vital 54 Transcona 56 Vol. 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins 1 Introduction Throughout history, generations of The ethnicity series is made up of three volumes: immigrants have arrived in Manitoba to start a new life. Their presence is 1. Foreign-born Population celebrated in our communities. Many This volume presents the population by country of birth. It focuses on the new immigrants, and a large number foreign-born population and its recent regional distribution across Manitoba.