Singing in ‘The Peg’: the Dynamics of Winnipeg Singing Cultures During the 20Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould's The

“What you intended to say”: Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould’s The Quiet in the Land Doreen Helen Klassen The Quiet in the Land is a radio documentary by Canadian pianist and composer Glenn Gould (1932-82) that features the voices of nine Mennonite musicians and theologians who reflect on their Mennonite identity as a people that are in the world yet separate from it. Like the other radio compositions in his The Solitude Trilogy—“The Idea of North” (1967) and “The Latecomers” (1969)—this work focuses on those who, either through geography, history, or ideology, engage in a “deliberate withdrawal from the world.”1 Based on Gould’s interviews in Winnipeg in July 1971, The Quiet in the Land was released by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) only in 1977, as Gould awaited changes in technology that would allow him to weave together snatches of these interviews thematically. His five primary themes were separateness, dealing with an increasingly urban and cosmopolitan lifestyle, the balance between evangelism and isolation, concern with others’ well-being in relation to the historic peace position, and maintaining Mennonite unity in the midst of fissions.2 He contextualized the documentary ideologically and sonically by placing it within the soundscape of a church service recorded at Waterloo-Kitchener United Mennonite Church in Waterloo, Ontario.3 Knowing that the work had received controversial responses from Mennonites upon its release, I framed my questions to former CBC radio producer Howard Dyck,4 one of Gould’s interviewees and later one of his 1 Bradley Lehman, “Review of Glenn Gould’s ‘The Quiet in the Land,’” www. -

January 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 A . " f ft.S. &. ft. P. deed not Ucende Some Recent Additions Select Your Choruses conceit cuid.iccitzt fotidt&{ to the Catalog of Oliver Ditson Co. NOW PIANO SOLOS—SHEET MUSIC The wide variety of selections listed below, and the complete AND PUBLISHERS in the THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS BMI catalogue of choruses, are especially noted as compo- MYRA ADLER Grade Pr. MAUDE LAFFERTY sitions frequently used by so many nationally famous edu- payment of the performing fee. Christmas Candles .3-4 $0.40 The Ball in the Fountain 4 .40 correspondence below reaffirms its traditional stand regarding ?-3 Happy Summer Day .40 VERNON LANE cators in their Festival Events, Clinics and regular programs. BERENICE BENSON BENTLEY Mexican Poppies 3 .35 The Witching Hour .2-3 .30 CEDRIC W. -

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: a Canadian Inner-City Case

Culturally Relevant Teacher Education: A Canadian Inner-City Case Rick Hesch winnipeg, manitoba This case study of an inner-city teacher education program documents the tensions at work on a social reconstructionist academic staff attempting to produce a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cultural relevance here includes three features: supporting academic achievement, maintaining cultural competence, and developing critical consciousness. All interests converge on the need to produce academically and technically competent teachers. Beyond this, the staff remain mindful of the dominant social and educational context within which they work and at the same time attempt to meet the longer-term interests of their students and culturally different inner-city communities. The possibilities for success have lessened in the political economy of the 1990s, but the study provides concrete instances of developing a culturally relevant teacher education program. Cette étude de cas portant sur un programme de formation à l’enseignement dans des écoles de quartiers défavorisés décrit les tensions au sein du personnel enseignant cher- chant à produire un programme de formation des maîtres culturellement significatif. Trois éléments définissent la pertinence culturelle d’un programme : il doit promouvoir la réussite scolaire, être adapté à la culture et développer une pensée critique. Tous les intervenants s’accordent sur la nécessité de produire des enseignants compétents. Cela dit, le personnel doit garder à l’esprit le contexte éducatif et social dominant dans lequel il travaille tout en essayant de tenir compte des intérêts à long terme des élèves et de diverses communautés culturelles implantées dans des quartiers défavorisés. L’étude fournit des exemples concrets de la marche à suivre pour élaborer un programme de formation à l’enseignement culturellement significatif. -

National Folk Song and Dance Ensemble Mazowsze 2021-10-04, 08:48

National Folk Song and Dance Ensemble Mazowsze https://www.mazowsze.waw.pl/en/news/666,Report-from-the-Family-Picnic-with-Mazowsze.html 2021-10-04, 08:48 Report from the Family Picnic with Mazowsze - thank you that you were with us! The open-air picnic with Mazowsze at Karolin, introducing the summer, is already over. The ensemble presented several shows for to the audience – concerts of various kinds of music: folk, classical, pop, and film music, for example from James Bond movies and Pirates of the Caribbean. The audience saw Mazowsze's soloists, choir, and orchestra, but also several guests. Among them, there were the renowned opera and operetta singers Dorota Laskowiecka and Adam Sobierajski, who sang for example “O mio babbino caro” from the opera Gianni Schicchi, “Nessun dorma” from Turandot, and the operetta fan favorite duet of Silva and Edwin from the operetta Die Csárdásfürstin [The Csardas Princess or The Riviera Girl]. The young, internationally renowned and awarded bass-baritone Łukasz Karauda, also presented opera repertoire on the stage. The singer, who has recently also become Mazowsze's soloist, sang “The Toreador Song” from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen. The concerts were conducted by Jacek Boniecki, Wojciech Gwiszcz, and Klemens Starybrat. It was a very special opportunity to listen to them, as each of them creates his own particular sound with the ensemble's orchestra. Mazowsze however, is not only music and singing – there is also dancing, performed by the ensemble's ballet. The program included pieces that allowed the dancers to show their versatility. There were the Polish national and regional dances Mazowsze is famous for, but also the classic tango (solo by Kamila Borowska and Adam Czechlewski) and waltz (solo by Dorota Rak and Marcos De Lima).Mazowsze 's performance wasn't the only occasion to see dance: there were also presentations prepared by the participants of the “Dancing with Mazowsze” workshops, and the performance prepared by the Folk Dance Ensemble “Pruszkowiacy”. -

Queen's Diamond Jubilee 2012

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee 2012 Background word ‘Yobel’, which refers to the ram or ram’s Queen Elizabeth ll has reigned over the United horn with which jubilee years were proclaimed. Kingdom and her Commonwealth countries for In Leviticus it states that such a horn or trumpet 60 years. 2012 and the Diamond Jubilee brings is to be blown on the tenth day of the seventh about many opportunities to celebrate, focus and month after the lapse of ‘seven Sabbaths of years’ give thanks for her Majesty’s faithful, gracious and (49 years) as a proclamation of liberty through - devoted service to the nations. out the land of the tribes of Israel. The year of jubilee was a consecrated year of ‘Sabbath- The Queen reached her 60th anniversary on the rest’ and liberty. During this year all debts were throne on 6 February 2012. On 12 March the cancelled, lands were restored to their original Queen attended Westminster Abbey to celebrate owners and family members were restored to one Commonwealth Day. Main celebrations will take another. place during an extended Bank Holiday weekend from 2 to 5 June. Coronation Day was on 2 June The year of jubilee was also central to the ministry 1953, and there are many stories of how people of of Jesus. In the Gospel of Luke Jesus makes the all ages remember spending that wonderful day. A claim to the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy in few homes had televisions and the BBC broadcast Isaiah 61:1–2. Jesus states that he has come to the Coronation to over 20 million viewers. -

01-Sargeant-PM

CERI OWEN Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs On Singing and Listening in Vaughan Williams’s Early Songs CERI OWEN I begin with a question not posed amid the singer narrates with ardent urgency their sound- recent and unusually liberal scholarly atten- ing and, apparently, their hearing. But precisely tion devoted to a song cycle by Ralph Vaughan who is engaged in these acts at this, the musi- Williams, the Robert Louis Stevenson settings, cal and emotional heart of the cycle? Songs of Travel, composed between 1901 and The recollected songs are first heard on the 1904.1 My question relates to “Youth and Love,” lips of the speaker in “The Vagabond,” an os- the fourth song of the cycle, in which an unex- tensibly archetypal Romantic wayfarer who in- pectedly impassioned climax erupts with pecu- troduces himself at the cycle’s opening in the liar force amid music of otherwise unparalleled lyric first-person, grimly issuing a characteris- serenity. Here, as strains of songs heard earlier tic demand for the solitary life on the open intrude into the piano’s accompaniment, the road. This lyric voice, its eye fixed squarely on the future, is retained in two subsequent songs, “Let Beauty Awake” and “The Roadside Fire” I thank Byron Adams, Daniel M. Grimley, and Julian (in which life with a beloved is contemplated).2 Johnson for their comments on this research, and espe- cially Benedict Taylor, for his invaluable editorial sugges- With “Youth and Love,” however, Vaughan tions. Thanks also to Clive Wilmer for his discussion of Williams rearranges the order of Stevenson’s Rossetti with me. -

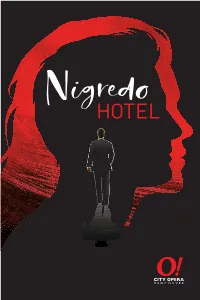

Nigredo Program

HOTEL CITY OPERA VANCOUVER PRESENTS HOTEL A one-act chamber opera by Nic Gotham and Ann-Marie MacDonald, commissioned in 1992 by Tarragon Theatre and Tapestry Opera, Toronto STARRING OCT 7 Tyler Duncan, Raymond • Sarah Vardy, Sophie Alan Corbishley • Stage Director Charles Barber • Music Director John Webber • Set and Lighting Design Barbara Clayden • Costume Design Jayson McLean • Production Manager Janet Lea and Nora Kelly • Producers COASTAL JAZZ PRESENTS Trudy Chalmers • General Manager KANDACE SPRINGS SUNDAY, OCTOBER 7 | 8PM | THE IMPERIAL TICKETS AT COASTALJAZZ.CA OR IN-PERSON AT RED CAT RECORDS @COASTALJAZZ This production is being given on the traditional territories of the Coast Salish peoples of the 1 Xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. 2 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR FROM THE STAGE DIRECTOR Charles Barber Alan Corbishley Welcome to the legendary Nigredo Hotel, In alchemy, nigredo, or blackness, means putrefaction or a bizarre, macabre and astonishing operatic thriller decomposition. Many alchemists believed that as a first step by Nic Gotham and Ann-Marie MacDonald. in the pathway to the philosopher’s stone, all alchemical As you will see, it is the story of an encounter between a beautiful ingredients had to be cleansed and cooked extensively to a but crazed woman who runs a shoddy hotel, and a brain surgeon uniform black matter. In analytical psychology, the term who takes refuge there after he crashes his car. became a metaphor ‘for the dark night of the soul, when Raymond and Sophie are two of the most unusual characters in an individual confronts the shadow within’… 20th C opera: brilliant, dazed, lonely, each possessing great insight into the other but little into themselves, sarcastic and corrosive, ...and this, in relation to the theories of famed psychologist Dr. -

The Politics of Innovation

The Future City, Report No. 2: The Politics of Innovation __________________ By Tom Axworthy 1972 __________________ The Institute of Urban Studies FOR INFORMATION: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg phone: 204.982.1140 fax: 204.943.4695 general email: [email protected] Mailing Address: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 515 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 THE FUTURE CITY, REPORT NO. 2: THE POLITICS OF INNOVATION Published 1972 by the Institute of Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg © THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES Note: The cover page and this information page are new replacements, 2015. The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. ' , I /' HT 169 C32 W585 no.Ol6 c.l E FUTURE .·; . ,... ) JI Report No.2 The Politics of Innovation A Publication of THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES University of Winnipeg THE FUTUKE CITY Report No. 2 'The Politics of Innovation' by Tom Axworthy with editorial assistance from Professor Andrew Quarry and research assistance from Mr. J. Cassidy, Mr. Paul Peterson, and Judy Friedrick. published by Institute of Urban Studies University of Winnipeg FOREWORD This is the second report published by the Institute of Urban Studies on the new city government scheme in Winnipeg. -

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

WINNIPEG DOWNTOWN PROFILE A Special Report on Demographic and Housing Market Factors in Winnipeg’s Downtown IUS SPECIAL REPORT JULY-2017 Institute of Urban Studies 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg P: 204 982-1140 F: 204 943-4695 E: [email protected] Mailing Address: 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 Author: Scott McCullough, Jino Distasio, Ryan Shirtliffe Data & GIS: Ryan Shirtliffe Research: Ryan Shirtliffe, Scott McCullough Supporting Research: Brad Muller, CentreVenture The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. Introduction This study undertakes an analysis of demographic and housing market factors that may influence the need for incentives in the downtown Winnipeg housing market. This report informs CentreVenture’s proposed “10 Year Housing Evaluation” and helps to address the proposed question, “What price do new downtown housing projects need to achieve to encourage more people to move downtown?” To accomplish this, the following have been undertaken: 1. A Demographic Analysis of current downtown Winnipeg residents with a comparison to Winnipeg medians, 2. A Rental Market Analysis comparing downtown rates to Winnipeg averages, as well as changing rental rates in the downtown from Census data, 3. -

Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca". Nam Yeung Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1997 Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca". Nam Yeung Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Yeung, Nam, "Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca"." (1997). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6648. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6648 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................