Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Point Douglas (“The North End”) a Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and Their Children

Point Douglas (“The North End”) A Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and their Children North Point Douglas Point Lord Selkirk Park Dufferin Douglas William Whyte Burrows Central St. Johns Neighbourhoods Luxton Inkster-Faraday Robertson Mynarski South Point Douglas This guide is produced and maintained by the WRHA Point Douglas Community Health Office. For editing, revisions or other information regarding content, please contact Vince Sansregret @ 204-(801-7803) or email: [email protected] INDEX Community Leisure and Recreation Centres Page 2 City of Winnipeg Fee Subsidy Program Page 3 Public Computer Access sites Page 3 Licensed Child Care Facilities Page 4-5 Food Banks/Free Community Meal programs Page 6 Cooking Programs – Food Security Page 7 Discount Clothing, Furniture, Household items Page 8 Community Support Programs Page 9-11 Programs for Expecting Parents and Families with infants Page 12 Libraries / Family Literacy Page 13 Parent and Child/Parenting Support Programs Page 14-15 City of Winnipeg Priceless Fun FREE Programming Page 16 FREE Child/Youth Recreation/‘drop-in’ Programs Page 17-19 Adult Ed.-Career Preparation Programs Page 20-21 Community, Leisure and Recreation Centres Luxton Community Centre 210 St. Cross St. Win Gardner-North End Wellness Phone: 204- 582-8249 Center - YMCA 363 McGregor St. Norquay Community Centre Phone: 204-293-3910 65 Granville St. Phone: 204-943-6897 Turtle Island Neighbourhood Centre 510 King St Sinclair Park Community Phone: 204-986-8346 Centre 490 Sinclair Ave. William Whyte Neighbourhood Phone: 204-582-8257 Association – Pritchard Park Recreation Centre Ralph Brown Community 295 Pritchard Ave. Centre Phone: 204-582 – 0988 460 Andrews Street Phone: 204-586-3149 Sgt. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

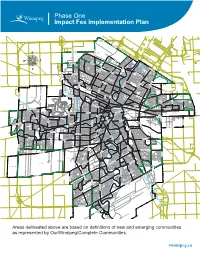

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

West Kildonan Committee Was Held This Day at 4:02 P.M

West Committee Room Council Building, Winnipeg June 8, 2010 A Meeting of the Lord Selkirk - West Kildonan Committee was held this day at 4:02 p.m. Members of the Committee: Councillor O’Shaughnessy, Chairperson Councillor Pagtakhan Winnipeg Public Service: Ms I. Skundberg, Clerk, City Clerk’s Department Mr. B. Buyachok, Real Property Officer, Planning, Property and Development Department Mr. S. Chapman, Traffic Studies Engineer, Public Works Department Mr. G. Doney, Senior Planner, Planning, Property and Development Department Ms S. Matile, Land Development Engineer, Planning, Property and Development Department Mr. K. Nixon, Active Transportation Coordinator, Public Works Department MOTIONS Moved by Councillor Pagtakhan, That Councillor Lazarenko be granted a leave of absence from today’s meeting due to a personal family matter. Carried Moved by Councillor Pagtakhan, That the minutes of the meeting held on May 11, 2010, be taken as read and confirmed. Carried Minutes - Lord Selkirk - West Kildonan Community Committee – June 8, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS DELEGATIONS 219. Wayne Conover, 817 Main North Point Douglas, Manor Tenant Advisory Committee (See Minute 230) 220. Anders Swanson, Co-Chair, W.R.E.N.C.H. (See Minute 237) 221. Richard Dudek, Vice-Presidemt. North Winnipeg Nomads Football Club Inc. (See Minute 239) REPORTS 222. Seven Oaks House Museum Board – Minutes 223. Applications for Citizen Member Appointments- Seven Oaks House Museum Board 224. Additional Appropriation – Western Canada Aviation Museum Inc. 225. Per Capita Grant - Luxton Playcentre Inc 226. Per Capita Grant – Edmund Partridge School Band Program 227. Per Capita Grant – 470 Pacific Tenant Association 228. Per Capita Grant – Dufferin School 229. -

Lead Concentrations in Soil in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods

Summary of Findings: Lead Concentrations in Soil in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods The Province of Manitoba, as represented by the Ministers of Health, Seniors and Active Living and Sustainable Development, commissioned an independent review of the potential health risks associated with lead in soils throughout the City of Winnipeg. This review was completed by a team led by Intrinsik Corp., in association with Habitat Health Impact Consulting, which included certified toxicologists, risk assessors, and a medical doctor. It included an evaluation of the benefits of conducting further investigations and provided recommendations regarding risk management and communication related to lead in soils. The work was completed between May and November 2019 and was divided into five tasks: • Task 1: Review of available soil data for Winnipeg neighbourhoods. • Task 2: Review of current and historical sources of lead in Winnipeg. • Task 3: Review of approaches used by Canadian and Western jurisdictions for assessing and managing lead in soil. • Task 4: Assessment of health risks associated with the lead concentrations measured in Winnipeg soils. • Task 5: Recommendations for further assessment of risks and possible risk management options. Summaries of the activities completed under each Task along with the key findings are presented below. Task 1: Review of Available Soil Data for Winnipeg Neighbourhoods Since the mid-1970s, the Province of Manitoba has completed several studies to measure the level of lead in Winnipeg soils. The focus was on the most recent studies completed by the Province, as well as a study conducted by the University of Manitoba for the neighbourhood of St. Boniface. All of the reported soil results were compared with the current health-based guideline for residential soils available from the Canadian Council for Ministers of the Environment. -

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc. 2021 Provincial Music & Arts Festival $12,000 Camerata Nova Inc. Performance of Medieval Inuit $15,000 Canzona Inc Performance of Cori Spezzati $3,750 Contemporary Verse 2 Inc. Technical upgrades and costs related to transi- $9,000 tioning to online programming Crescent Fort Rouge United Church Community Activities Manager $7,500 Dancer Transition Resource Centre DRTC's Manitoba-based programming $5,000 Folk Arts Council of Winnipeg, Inc. Priority short-term operating costs $45,000 Friends of Dalnavert Museum Inc. Storytelling program at Dalnavert Museum $5,000 Gas Station Arts Centre Priority feasibility study costs $20,000 Graffiti Art Programming Inc. Free arts mentorship and after-school program- $25,000 ming to young artists in an adapted format Green Kids Inc Bike and Circuses summer 2021 performances $5,000 Manitoba Band Association Inc. 2021 Manitoba Band, Solo, & Ensemble Festival $30,000 Manitoba Chamber Orchestra Inc. Costs related to producing an online 2021 con- $20,000 cert season Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library Digital collections project $10,000 Inc. Manitoba Genealogical Society Inc. Priority costs related to website improvements $7,000 and developing a social media strategy Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Short-term operating costs $45,000 Centre Inc. One Trunk Theatre Inc. Priority aspects of the Transformation project $10,000 Plug-In Inc Priority project costs related to Stages 2021 $20,000 Prairie Fire Press Inc. Costs related to coordinating Prairie Fire Univer- $7,000 sity Royal Aviation Museum of Western Priority costs related to public and oral history $5,000 Canada Inc. -

Adult Nuisance Mosquito Fogging Program Starts Tonight

Adult Nuisance Mosquito Fogging Program starts tonight Winnipeg, MB – The City of Winnipeg will start its adult nuisance mosquito fogging program tonight at 9:30 p.m. Crews will treat in Insect Management Areas 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, and 51. This includes the following neighbourhoods: Insect Management Area Neighbourhoods 34 Assiniboia Downs, Buchanan, Kirkfield, Glendale, Westwood 35 Crestview, Heritage Park, Saskatchewan North, Sturgeon Creek Birchwood, Booth, Jameswood, Murray Industrial Park, Silver Heights, 36 Woodhaven 37 Airport 38 Bruce Park, Deer Lodge, King Edward 39 Brooklands, Sargent Park, St. James Industrial 40 Kensington, Minto, Polo Park, St. Matthews, West Wolseley Armstrong Point, Broadway - Assiniboine, Legislature, Portage & Main, 41 South Portage, The Forks, West Broadway, Wolseley Central Park, Colony, Daniel McIntyre, Portage - Ellice, Spence, West 42 Alexander North Inkster Industrial, Oakpoint Highway, Omand's Creek Industrial, 43 Tyndall Park Burrows - Keewatin, Inkster Industrial Park, Mynarski, Pacific Industrial, 44 Shaughnessy Park, Weston, Weston Shops 45 Burrows Central, Robertson, William Whyte Centennial, China Town, Civic Centre, Dufferin, Dufferin Industrial, 46 Exchange District, Logan C.P.R., Lord Selkirk Park, North Point Douglas, South Point Douglas 47 Inkster - Faraday, Luxton, St. John's, St. John's Park 48 Inkster Gardens, Mandalay West, The Maples Garden City, Leila - McPhillips Triangle, Margaret Park, Templeton - 49 Sinclair 50 Jefferson, Kildonan Park, Seven Oaks Amber Trails, Leila North, Riverbend, Rivergrove, Rosser - Old Kildonan, 51 West Kildonan Industrial Fogging will take place until 6:30 a.m. tomorrow. Daily public service announcements Public Service Announcements (PSAs) will be released daily at least eight hours in advance of planned fogging. -

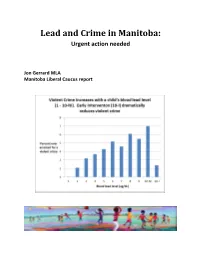

Lead and Crime in Manitoba: Urgent Action Needed

Lead and Crime in Manitoba: Urgent action needed Jon Gerrard MLA Manitoba Liberal Caucus report “Lead poisoning is the most significant and prevalent disease of environmental origin in US children” -Silbergeld 1997 Lead exposure contributing to violence and crime is, “a public health crisis with serious social justice implications” -Emer et al 2020 “mounting evidence [supports] that preschool lead exposure affects the risk of criminal behavior later in life. … especially affects juvenile offending and related trends in index crime (mainly property crime rates and burglary)… Violent crime trends and shifts to higher adult arrest rates suggest blood lead also affects violent and repeat offending.” -Nevin 2007 “The hypothesis that murder rates are especially affected by severe lead poisoning is consistent with international and racial contrasts and a cross-sectional analysis of average 1985-1994 USA city murder rates.” -Nevin 2007 “1941-1975 gasoline lead use explained 90% of the 1964-1998 variation in USA violent crime.” - Economist Rick Nevin, from a study published in 2000, and reported by CTV news March 7, 2013 “We can either attack crime at its root by getting rid of the remaining lead in our environment, or we can continue our current policy of waiting 20 years and then locking up all the lead-poisoned kids who have turned into criminals.” -Drum 2016 “Cleaning up the rest of the lead that remains in our environment could turn out to be the cheapest, most effective crime prevention tool we have.” -Drum 2016 “Children found to have a blood lead level higher than 5 ug/dL (0.24 umol/L) should be investigated thoroughly and any identified exposure sources should be mitigated as soon as possible.” - Canadian Pediatric Society 2019 “The impact of lead is intergenerational. -

City of Winnipeg Comprehensive Housing Needs Assessment

CITY OF W INNIPEG C OMPREHENSIVE H OUSING N EEDS A SSESSMENT JAN-2020 Institute of Urban Studies 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg P: 204 982-1140 E: [email protected] Mailing Address: 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 © The City of Winnipeg Authors (alphabetically): Dr. Tom Carter Institute of Urban Studies (ret.) Tom Janzen Scatliff + Miller + Murray Scott McCullough Institute of Urban Studies Ryan Shirtliffe Institute of Urban Studies Evan Sinclair Scatliff + Miller + Murray Contributing Authors: Elliott Hannam BW Ferguson & Associates Ltd. Brett Ferguson BW Ferguson & Associates Ltd. Data Assembly, Database, and GIS mapping: Ryan Shirtliffe Institute of Urban Studies Reviewers: Noah Yauk PP&D, City of Winnipeg Jessica Lam PP&D, City of Winnipeg Tyler Kroeker Corporate Finance, City of Winnipeg Tyler Markowsky Corporate Finance, City of Winnipeg Suggested Citation: Carter, Tom, Tom Janzen, Scott McCullough, Ryan Shitliffe, Evan Sinclair (2020). City of Winnipeg Comprehensive Housing Needs Assessment. Institute of Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg. Front Cover Photo: Ryan Sharpe. (2017) “An aerial photograph of the meandering Red River in Winnipeg, Manitoba.” Wikipedia Commons. Used with permission. The photo shows the neighbourhoods of Riverview, Lord Roberts and Earl Grey in the foreground; McMillan, Osborne Village, part of Downtown, Norwood and St. Boniface in the mid-ground; and Point Douglas, with East Kildonan stretching to the horizon in the background. City of Winnipeg Comprehensive Housing Needs Assessment Contents -

Property Taxes and Built Form: Mapping the City of Winnipeg By: Felipe A

Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg$ X.xx - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - -

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED in 2018 (Winnipeg

ORGANIZATIONS FUNDED IN 2018 (Winnipeg - sorted by area) ORGANISATIONS FINANCÉES EN 2018 (Winnipeg - classées par secteur) Charleswood-Tuxedo Archers & Bowhunters Assoc of MB Assiniboine Park Conservancy Canadian Mennonite University Family Dynamics of Winnipeg Fort Whyte Alive Friends of the Harte Trail Grace Community Church Manitoba Cycling Association Manitoba Sailing Assoc. Nature Manitoba Oasis Community Church Purple Loosestrife Project of Manitoba Rotary Club of Winnipeg - Charleswood Varsity View Community Centre Winnipeg Military Family Resource Centre Winnipeg South Minor Baseball Association Daniel McIntyre Daniel McIntyre / St. Matthew's Comm. Assoc. Emmanuel Mission Church Ethio-Canadian Cultural Academy Girls with Pride and Dignity Foundation Living Bible Explorers (Winnipeg) Mission Baptist Church Monyjang Society of Manitoba Mood Disorders Association of Manitoba Robert A. Steen Memorial Community Centre Sargent Park Lawn Bowling Club Spence Neighbourhood Assoc. Valour Community Centre West Central Community Program West Central Women's Resource Centre West End BIZ Wii Chii Waakanak Learning Centre Winnipeg Art Gallery Winnipeg School Division (special needs project) Elmwood-East Kildonan Bronx Park Community Centre Chalmers Community Centre Chalmers Neighbourhood Renewal Corp. Congo Canada Charity Foundation East Elmwood Community Centre Elmwood Community Resource Centre Elmwood Giants Baseball Club Elmwood Mennonite Brethren Church Frontier College Hope Centre Ministries One Hope Min. of Canada-Adventure Day Camp River -

There Is an Alternative

Fast FACTSCANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES - MANITOBA June 12, 2017 The Pallister Government and the Path to Reconciliation Act First published in the Winnipeg Free Press June 8, 2017 On Friday May 26, I attended an impromptu develop a strategy for reconciliation that alternative. event organized by supporters of the North “builds upon meaningful engagement Point Douglas Women’s Centre. The event with Indigenous nations and Indigenous was held to show support for the Centre, peoples…” which was reeling from the news that it I wondered, what the strategy was? Did would not receive an expected $120,000 Minister Clarke consult with Indigenous required for its operations. This represents women in North Point Douglas before one third of the Centre’s budget and losing cutting funding to their Centre? Did it means that North Point Douglas Women’s the Minister consult with the many Centre will be forced to cut important Indigenous women who use the services programs that are serving the community of the North End Women’s Centre, well. It got me thinking about reconciliation. which has also been informed that it Indigenous women spoke passionately will receive less funding this year? And about the important role the Centre plays in what about the many other services their lives. They spoke about the culturally that have lost funding, or are waiting to there is an based programs that are helping them to hear of their fate, but are too nervous heal from intergenerational trauma caused to talk about it? Most if not all of these by government policies and programs like organizations employ Indigenous people residential schools.