Duras and Indochina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De La Littérature-Monde a L'identité-Monde

XXI Colloque APFUE - Barcelona-Bellaterra, 23-25 Mai 2012 De la littérature-monde a l’identité-monde: múltiples identidades en pro de una misma literatura María Loreto Cantón Rodríguez Universidad de Almería [email protected] Resumen Proponemos una valorización del movimiento littérature-monde, en su dimensión historiográfíca y autoexplicativa. El concepto, lanzado por un grupo de 44 escritores a través del manifiesto publicado en Le Monde des Livres el 16 de marzo de 2007, dio lugar a la aparición del libro con el mismo título formado por un conjunto de artículos de algunos de los firmantes del manifiesto. Tres años después los editores de esta obra, Michel Le Bris y Jean Rouaud, publicaron un segundo volumen con el título de Je est un autre: Pour une identité-monde. Sus principales novedades radican en la redefinición de conceptos como el de francofonía, identidad, alteridad e incluso el propio concepto de mundo en su relación con la literatura. Palabras-clave Littérature-monde, identidad, francofonía, alteridad, espacio literario. 1 El Manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français: principios y reivindicaciones El interés de un manifiesto literario no es siempre la profundidad, la novedad o la relevancia de sus fundamentos artísticos, sino muchas veces su oportunidad para avivar el debate intelectual sobre el papel de la literatura en cada momento histórico. Los postulados reivindicativos del Manifeste pour une littérature-monde giran en torno a unos temas comunes que ya habían sido planteados años atrás por críticos y escritores. Las teorías lingüísticas no podían dar respuesta a los fenómenos que se planteaban más allá del texto en torno a conceptos de identidad, cultura, nación, etc. -

Litterature Francaise Contemporaine

MASTER ’S PROGRAMME ETUDES FRANCOPHONES 2DYEAR OF STUDY, 1ST SEMESTER COURSE TITLE LITTERATURE FRANCAISE CONTEMPORAINE COURSE CODE COURSE TYPE full attendance COURSE LEVEL 2nd cycle (master’sdegree) YEAR OF STUDY, SEMESTER 2dyear of study,1stsemester NUMBER OF ECTS CREDITS NUMBER OF HOURS PER WEEK 2 lecture hours+ 1 seminar hour NAME OF LECTURE HOLDER Simona MODREANU NAME OF SEMINAR HOLDER ………….. PREREQUISITES Advanced level of French A GENERAL AND COURSE-SPECIFIC COMPETENCES General competences: → Identification of the marks of critical discourse on French literature, as opposed to literary discourse; → Identification of the main moments of European and especially French culture that reflect the idea of modernity; → Indentification of the marks of the modern and contemporary dramatic discourse, as opposed to the literary discourse in prose and poetry; → Identification of the stakes of critical and theoretical discourse, as well as of the modern dramatic one, according to the historical and cultural context in which the main studied currents appear; → Interpretative competences in reading the studied texts and competence of cultural analysis in context. Course-specific competences: → Skills of interpretation of texts; → Skills to identify the cultural models present in the studied texts; → Cultural expression skills and competences; B LEARNING OUTCOMES → Reading and interpretation skills of theoretical texts that is the main argument for the existence of a literary French metadiscourse → Understanding the interaction between literature and culture in modern and contemporary society and the possibility of applying this in connection with other types of cultural content; C LECTURE CONTENT Introduction; preliminary considerations Characteristics; evolutions of contemporary French literature. The novel - the dominant genre. -

Cahier De LECTURES - 2004 À 2018

Cahier de LECTURES - 2004 à 2018 Afrique : • « Ébène, aventures africaines» Ryszard Kapuscinski Pocket p 175 Un journaliste, amoureux de l'Afrique nous aide à comprendre ce continent • Africa Trek1 Sonia et Alexandre Poussin p 181 Un couple remonte l'Afrique à pied d'Afrique du sud à Jérusalem le tome 1 rend compte des 7000 km du sud de L'Afrique du Sud au Kilimandjaro (Tanzanie) • Dernières nouvelles de Françafrique vents d'ailleurs 2003 p 3 13 nouvelles d'auteurs africains qui traitent des rapports entre la France et l'Afrique suivi d'un hommage à Mongo Béti (Camerounais) par sa compagne qui parle de ses derniers moments. • Un fusil dans la main, un poème dans la poche Emmanuel Dongala Le serpent à plume 2003 p 3 • Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali Gil Courtemanche Boréal (Québec) p 3 • Petit Pays Gaël Faye Grasset 2016 II p • « Petit précis de remise à niveau sur l'histoire africaine à l'usage du président Sarkozy » sous la direction de Adame Ba Konaré p 108 En 2007, Sarkozy et ses conseillers, remplis des préjugés développés depuis « le temps béni des colonies », fait à Dakar un discours désastreux. Un certain nombre de chercheurs et spécialistes africains et autres cherchent à combler ses lacunes et nous aident à combler les nôtres. • « Togo, de l'esclavage au libéralisme mafieux » Gilles Labarth Agone p 103 • Les cigognes sont immortelles Alain Mabancou Seuil 2018 II p 81 Anarchie : voir commentaires • « L'anarchie, une histoire de révolte » Claude Faber Les Essentielles Milan p 20 Un livret de soixante pages. -

De L'autre Coté Du Periph': Les Lieux De L'identité Dans Le Roman Feminin

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France Mame Fatou Niang Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Niang, Mame Fatou, "De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1740. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1740 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DE L’AUTRE COTÉ DU PERIPH’ : LES LIEUX DE L’IDENTITÉ DANS LE ROMAN FEMININ DE BANLIEUE EN FRANCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Mame Fatou Niang Licence, Université Lyon 2 – 2005 Master 2, Université Lyon 2 –2008 August 2012 A Lissa ii REMERCIEMENTS Cette thèse n’aurait pu voir le jour sans le soutien de mon directeur de thèse Dr. Pius Ngandu Nkashama. Vos conseils et votre sourire en toute occasion ont été un véritable moteur. Merci pour toutes ces fois où je suis arrivée dans votre bureau sans rendez-vous, en vous demandant si vous aviez « 2 secondes » avant de m’engager dans des questions sans fin. -

Écrire Sa Vie, Vivre Son Écriture

NETTA NAKARI Écrire sa vie, vivre son écriture The Autobiographical Self-Reflection of Annie Ernaux and Marguerite Duras ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of the School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Auditorium Pinni B 1096, Kanslerinrinne 1, Tampere, on September 27th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE NETTA NAKARI Écrire sa vie, vivre son écriture The Autobiographical Self-Reflection of Annie Ernaux and Marguerite Duras Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1966 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies Finland The originality of this thesis has been checked using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service in accordance with the quality management system of the University of Tampere. Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1966 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1451 ISBN 978-951-44-9547-2 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9548-9 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Acknowledgments There is a tremendous amount of people who have made this project possible. Here, I hope to express my gratitude to at least a fraction of them. First and foremost I would like to thank my supervisors, both current and past. Pekka Tammi’s determination, encouragement and razor-sharp observations on the smallest details of the countless versions of my text have seizelessly pushed me to always do better and better. -

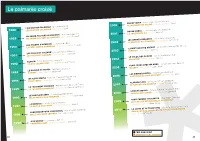

Le Palmarès Croisé

Le palmarès croisé 1988 L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) INGRID CAVEN - Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Gallimard) L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) 2000 ALLAH N’EST PAS OBLIGÉ - Ahmadou Kourouma (Seuil) UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) ROUGE BRÉSIL - Jean-Christophe Rufin (Gallimard) 1989 UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) 2001 LA JOUEUSE DE GO - Shan Sa (Grasset) LES CHAMPS D’HONNEUR - Jean Rouaud (Minuit) LES OMBRES ERRANTES - Pascal Quignard (Grasset) 1990 LE PETIT PRINCE CANNIBALE - Françoise Lefèvre (Actes Sud) 2002 LA MORT DU ROI TSONGOR - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) 1991 LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) LA MAÎTRESSE DE BRECHT - Jacques-Pierre Amette (Albin Michel) LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) 2003 FARRAGO - Yann Apperry (Grasset) TEXACO - Patrick Chamoiseau (Gallimard) 1992 LE SOLEIL DES SCORTA - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) L’ÎLE DU LÉZARD VERT - Edouardo Manet (Flammarion) 2004 UN SECRET - Philippe Grimbert (Grasset) 1993 LE ROCHER DE TANIOS - Amin Maalouf (Grasset) TROIS JOURS CHEZ MA MÈRE - François Weyergans (Grasset) CANINES - Anne Wiazemsky (Gallimard) 2005 MAGNUS - Sylvie Germain (Albin Michel) 1994 UN ALLER SIMPLE - Didier Van Cauwelaert (Albin Michel) LES BIENVEILLANTES - Jonathan Littell (Gallimard) BELLE-MÈRE - Claude Pujade-Renaud (Actes Sud) 2006 CONTOURS DU JOUR QUI VIENT - Léonora Miano (Plon) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS - Andreï Makine (Mercure de France) 1995 ALABAMA SONG - Gilles Leroy (Mercure de France) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS -

And the Author in Modern French Autobiography Marguerite Duras and Annie Ernaux

Vol. 1, 259-270 ISSN: 0210-7287 THE «I» AND THE AUTHOR IN MODERN FRENCH AUTOBIOGRAPHY MARGUERITE DURAS AND ANNIE ERNAUX El «yo» y el autor en la autobiografía francesa moderna de Marguerite Duras y Annie Ernaux Netta NAKARI University of Tampere [email protected] Recibido: marzo de 2013; Aceptado: mayo de 2013; Publicado: diciembre de 2013 BIBLID [0210-7287 (2013) 3; 259-270] Ref. Bibl. NETTA NAKARI. THE «I» AND THE AUTHOR IN MODERN FRENCH AUTOBIOGRAPHY MARGUERITE DURAS AND ANNIE ERNAUX. 1616: Anuario de Literatura Comparada, 3 (2013), 259-270 RESUMEN: La emergencia de lo individual ha dominado durante algún tiempo la esfera pública francesa. Esto es especialmente notable cuando se trata de la escritura autobiográfica. Las obras de Marguerite Duras y Annie Ernaux se centran en el individuo y la relación entre el «yo» y la figura del autor en términos generales, y nos proporcionan diversas claves sobre la importancia de la escritura autobiográfica en relación con sus vidas y personalidades. En el análisis de lo individual en su obra son especialmente relevantes los múltiples estratos de autoconsciencia. Palabras clave: Marguerite Duras, Annie Ernaux, Autobiografía Francesa, Lo Individual, Autoconsciencia. © Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca 1616: Anuario de Literatura Comparada, 3, 2013, pp. 259-270 260 NETTA NAKARI THE «I» AND THE AUTHOR IN MODERN FRENCH ABSTRACT: The emergence of the individual has for some time now domi- nated the public field in France. This is especially visible when it comes to autobiographical writing. Marguerite Duras’s and Annie Ernaux’s works address the focus on the individual and the relationship between the «I» and the author in general, and also hold various clues to the importance of autobiographical writing to their lives and personalities. -

WARREN F. MOTTE JR. Department of French and Italian 3374 16Th

WARREN F. MOTTE JR. Department of French and Italian 3374 16th Street University of Colorado Boulder Boulder, Colorado 80309-0238 Colorado 80304 Tel: 303-492-6993 Tel: 303-440-4323 [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania French Literature 1981 A.M. University of Pennsylvania French Literature 1979 Maîtrise Université de Bordeaux Anglo-American Literature 1976 A.B. University of Pennsylvania English Literature 1974 INTERESTS Contemporary French Literature Comparative Literature Theory of Literature Literary Experimentalism POSITIONS HELD DISTINGUISHED PROFESSOR, University of Colorado, 2018- COLLEGE PROFESSOR OF DISTINCTION, University of Colorado, 2016- PROFESSOR, University of Colorado, 1991- ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, University of Colorado, 1987-91 ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, University of Nebraska, 1986-87 ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, University of Nebraska, 1982-86 LECTEUR, Université de Bordeaux, 1975-77 TEACHING FELLOW, University of Pennsylvania, 1974-75; 1977-82 Motte 2 PUBLICATIONS BOOKS The Poetics of Experiment: A Study of the Work of Georges Perec (Lexington: French Forum Monographs, 1984). Questioning Edmond Jabès (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990). Playtexts: Ludics in Contemporary Literature (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995). Small Worlds: Minimalism in Contemporary French Literature (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999). Fables of the Novel: French Fiction Since 1990 (Normal: Dalkey Archive Press, 2003). Fiction Now: The French Novel in the Twenty-First Century (Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, 2008). Mirror Gazing (Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, 2014). French Fiction Today (Victoria: Dalkey Archive Press, 2017). EDITED VOLUMES Oulipo: A Primer of Potential Literature (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986). Translated and edited. Rev. ed. Normal: Dalkey Archive Press, 1998; rpt. 2007. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The expressed and the inexpressible in the theatre of Jean-Jacques Bernard and Henry Rene Lenormand between 1919 and 1945 Winnett, Prudence J. How to cite: Winnett, Prudence J. (1996) The expressed and the inexpressible in the theatre of Jean-Jacques Bernard and Henry Rene Lenormand between 1919 and 1945, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5102/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE EXPRESSED AND THE INEXPRESSIBLE IN THE THEATRE OF JEAN-JACQUES BERNARD AND HENRY-RENE LENORMAND BETWEEN 1919 AND 1945 ' PRUDENCE J. WINNETT, M.A. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of French, School of Modern European Languages, University of Durham The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Le Printemps Du Livre De Cassis La MEVA Hôtel Martin Sauveur - 4 Rue Séverin Icard -13260 Cassis Tél

Printemps du livre Cassis du 30 mai au 2 juin avec la participation de nombreux écrivains : Tahar Ben Jelloun Serge Joncour Régis Wargnier Alexandre Jardin Vanessa Schneider Pierre Palmade Cali Arnaud Le Guerne Pierre Ducrozet Elizabeth Tchoungui Eric Emmanuel Schmitt Laurent Seksik Jean-Jacques Annaud Olivier Pourriol Serge Moati Luciano Melis Rudy Ricciotti Rencontres Littéraires conçues et animées par Patrick POIVRE D’ARVOR et Marc Fourny VENDREDI 31 MAI À 11H30 Cour d’Honneur de la Mairie de Cassis INAUGURATION par Danielle Milon, Maire de Cassis Officier de la Légion d’Honneur Vice-Présidente de la Métropole Aix-Marseille-Provence Vice-Présidente du Conseil Départemental En présence des écrivains invités et de nombreuses personnalités. 11h30 à 12h00 : Jazz avec «Le Trio Tenderly» EXPOSITION D’UNE COLLECTION PRIVÉE DE PEINTURES aux Salles Voûtées de la Mairie des œuvres de Jean Peter TRIPP «Au commencement était le verbe...» du 30 Mai au 10 Juin 2019 inclus Printemps du livre Cassis du 30 mai au 2 juin Le Printemps du Livre de Cassis, créé en 1986 par Danielle Milon, fête ses trente et un ans cette année. Il conjugue littérature, musique, arts plastiques, photographie et cinéma. Cette véritable fête de l’écriture se déclinera cette année encore sur un week-end de quatre jours, pour le week-end de l’Ascension, dans le cadre magique de l’amphithéâtre de la Fondation Camargo. A l’occasion du Printemps du Livre de Cassis, création d’une étiquette spéciale par Nicolas Bontoux Bodin, Château de Fontblanche. Retour en images sur l’édition -

Pratiques Durassiennes Sous Pastiche Oulipien

Pratiques durassiennes sous pastiche oulipien Joël JULY CIELAM, EA 4235 Université d'Aix Marseille (AMU) Résumé : A partir d'un court texte de l'auteur oulipien Hervé Le Tellier, et en confrontant son travail à d'autres imitations moins réussies du style durassien, nous tenterons de dégager ce qui relève de la parodie (thème du regard et notamment du regard biaisé, mention ironique) et ce qui relève du pastiche (temps verbaux, pronoms, parataxe). L'habileté de cette contrefaçon repose surtout sur le point de vue paradoxal, cher à Duras, à travers lequel dans une syntaxe limpide l'évidence devient mystère. Examiner comment tel ou tel pasticheur imite tel modèle permet de poser (seule façon d’un jour les résoudre) tous les problèmes de la description d’un style singulier – en particulier, question épineuse, la définition du « stylème ». Il n’y a de texte que lu et si le pastiche n’est jamais qu’une lecture écrite, alors il est particulièrement prometteur d’aborder la question dite du « style individuel » à travers une comparaison la plus serrée possible des divers pastiches auxquels l’œuvre a donné lieu ( Daniel BILOUS, « Sur la mimécriture. Essai de typologie », in Du pastiche, de la parodie et de quelques notions connexes, Editions Nota bene, 2004, p. 130). Hervé Le Tellier, né en 1957, a été coopté à l'OuLiPo en 1992 et a écrit une thèse sur ce mouvement en 20021. C'est dire si sa production abondante et variée [peux-tu rappeler brièvement rappeler en quoi sa production consiste, nombre de livres et genres ?] reste pétrie de considérations techniques. -

Références D'articles Ou De Textes Courts Classées Par Périodiques Ou Recueils

Interrogation de la banque de données Limag le samedi 7 juillet 2001 Références d'articles ou de textes courts classées par périodiques ou recueils N.B.: Lorsque des articles sont accompagnés d'un lien vers Internet, en caractères bruns, il suffit de cliquer sur ce lien pour accéder au texte de l'article ou à un complément d'information sur Internet. (Cette fonction n'est cependant accessible que sur le site Internet, en format Acrobat) Copyright Charles Bonn & CICLIM 24 heures. Lausanne, Périodique 1994 8 février FREY, Pascale. Tahar Ben Jelloun s'attaque à la corruption... et à l'amitié. CR de "L'Homme rompu" & de "La Soudure fraternelle". Même article et même mise en page dans "La Tribune de Genève" du 9 février. A.D.I.S.E.M. Kateb Yacine et la modernité textuelle. Alger, O.P.U., Actes de colloque. 1992 HIMEUR, Ouarda. p. 41-55. Le traitement de l'oralité: de Kateb à Ben Jelloun. BONN, Charles. p. 106-119. Variations katébiennes de la modernité littéraire maghrébine: l'ombre du père et la séduction interlinguistique. ACHOUR, Christiane. http://www.limag.com/Pagespersonnes/Achour.htm (Dir.). Cahiers Jamel Eddine Bencheikh. Savoir et imaginaire. Paris, L'Harmattan/Université Paris 13, Recueil de textes. 1998 , BONN, Charles. p. 103-109. Ecriture romanesque, lectures idéologiques et discours d'identité au Maghreb: une parole problématique. (Dir.) MORSLY, Dalila. (Dir.). Voyager en langues et littératures. Alger, OPU, Ed. 2667. Essai 1990 GONTARD, Marc. p. 87-96. L'itinéraire comme forme romanesque chez Tahar Ben Jelloun et Abdelwahab Meddeb. ADAMSON, Ginette. & GOUANVIC, Jean-Marc.