La Banlieue: Life on the Edge by Marguerite Feitlowitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De La Littérature-Monde a L'identité-Monde

XXI Colloque APFUE - Barcelona-Bellaterra, 23-25 Mai 2012 De la littérature-monde a l’identité-monde: múltiples identidades en pro de una misma literatura María Loreto Cantón Rodríguez Universidad de Almería [email protected] Resumen Proponemos una valorización del movimiento littérature-monde, en su dimensión historiográfíca y autoexplicativa. El concepto, lanzado por un grupo de 44 escritores a través del manifiesto publicado en Le Monde des Livres el 16 de marzo de 2007, dio lugar a la aparición del libro con el mismo título formado por un conjunto de artículos de algunos de los firmantes del manifiesto. Tres años después los editores de esta obra, Michel Le Bris y Jean Rouaud, publicaron un segundo volumen con el título de Je est un autre: Pour une identité-monde. Sus principales novedades radican en la redefinición de conceptos como el de francofonía, identidad, alteridad e incluso el propio concepto de mundo en su relación con la literatura. Palabras-clave Littérature-monde, identidad, francofonía, alteridad, espacio literario. 1 El Manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français: principios y reivindicaciones El interés de un manifiesto literario no es siempre la profundidad, la novedad o la relevancia de sus fundamentos artísticos, sino muchas veces su oportunidad para avivar el debate intelectual sobre el papel de la literatura en cada momento histórico. Los postulados reivindicativos del Manifeste pour une littérature-monde giran en torno a unos temas comunes que ya habían sido planteados años atrás por críticos y escritores. Las teorías lingüísticas no podían dar respuesta a los fenómenos que se planteaban más allá del texto en torno a conceptos de identidad, cultura, nación, etc. -

Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 087 919 CB 001 018 AUTHOR Hayes, Philip TITLE Guide to the Preparation of an Area of Distribution Manual. INSTITUTION Clemson Univ., S.C. Vocational Education Media Center.; South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. Office of Vocational Education. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 100p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$4.20 DESCRIPTORS Business Education; Clothing Design; *Distributive Education; *Guides; High School Curriculum; Manuals; Student Developed Materials; *Student Projects IDENTIFIERS *Career Awareness; South Carolina ABSTRACT This semester-length guide for high school distributive education students is geared to start the student thinking about the vocation he would like to enter by exploring one area of interest in marketing and distribution and then presenting the results in a research paper known as an area of distribution manual. The first 25 pages of this document pertain to procedures to follow in writing a manual, rules for entering manuals in national Distributive Education Clubs of America competition, and some summary sheet examples of State winners that were entered at the 25th National DECA Leadership Conference. The remaining 75 pages are an example of an area of distribution manual on "How Fashion Changes Relate to Fashion Designing As a Career," which was a State winner and also a national finalist. In the example manual, the importance of fashion in the economy, the large role fashion plays in the clothing industry, the fast change as well as the repeating of fashion, qualifications for leadership and entry into the fashion world, and techniques of fabric and color selection are all included to create a comprehensive picture of past, present, and future fashion trends. -

San Marino and Beaver Creek Campuses

SOUTHWESTERN ACADEMY San Marino and Beaver Creek Campuses STUDENT HANDBOOK for 2018 - 2019 STUDENT: _______________________________________________ STUDENT NUMBER: _______________________ EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] GRADE: ________ For initial class placements - subject to change as needed ADVISOR: _______________________________ EXT: _________ ASSEMBLY SEAT: ________________ BOOK LOCKER: _________ FIRST or SECOND LUNCH DINING ROOM: _______ TABLE: _____ GYM LOCKER NUMBER: ___________ PE: ___________ DORMITORY: _______________________________ROOM: _______ ROOMMATE'S NAME: ______________________________ DORM PARENT'S NAME: ___________________ EXT: ________ YOUR TEAM: ____________________________________________ SOUTHWESTERN ACADEMY STUDENT HANDBOOK FOR 2018-2019 A propriety document Not to be reproduced or distributed without permission © 2018 by the Board of Trustees Southwestern Academy San Marino, California 91108 2 Southwestern Academy ACADEMIC GOALS San Marino and Beaver Creek SOUTHWESTERN'S SCHOOLWIDE Campuses LEARNING OBJECTIVES These are the goals you are to accomplish in Student Handbook completing high school with our college-recom- mending diploma. All our classes, activities, and experiences work together to form these results. 2018 - 2019 Upon graduation with a college-recom- SOUTHWESTERN’S 95th YEAR mending diploma from Southwestern's 12th grade, every student will: --be qualified to enter and have the potential to NOTE: This “Red Book” student handbook and succeed at an appropriate college, university, or the assignment pages are important tools for community college; your success. Each student receives a binder and a copy of this handbook at the beginning of the term. You must bring this “Red Book” --be capable of reading, writing, and in its binder to all classes throughout the understanding English and have sufficient English year. proficiency to enter an American college or university; This information will be reviewed in classes on the first day of school. -

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

1 Matt Phillips, 'French Studies: Literature, 2000 to the Present Day

1 Matt Phillips, ‘French Studies: Literature, 2000 to the Present Day’, Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, 80 (2020), 209–260 DOI for published version: https://doi.org/10.1163/22224297-08001010 [TT] Literature, 2000 to the Present Day [A] Matt Phillips, Royal Holloway, University of London This survey covers the years 2017 and 2018 [H2]1. General Alexandre Gefen, Réparer le monde: la littérature française face au XXIe siècle, Corti, 2017, 392 pp., argues that contemporary French literature has undergone a therapeutic turn, with both writing and reading now conceived in terms of healing, helping, and doing good. G. defends this thesis with extraordinary thoroughness as he examines the turn’s various guises: as objects of literature’s care here feature the self and its fractures; trauma, both individual and collective; illness, mental and physical; mourning and forgetfulness, personal and historical; and endangered bonds, with humans and beyond, on local and global scales. This amounts to what G. calls a new ‘paradigme clinique’ and, like any paradigm shift, this one appears replete with contradictions, tensions, and opponents, not least owing to the residual influence of preceding paradigms; G.’s analysis is especially impressive when unpicking the ways in which contemporary writers negotiate their sustained attachments to a formal, intransitive conception of literature, and/or more overtly revolutionary political projects. His thesis is supported by an enviable breadth of reference: G. lays out the diverse intellectual, technological, and socioeconomic histories at work in this development, and touches on close to 200 contemporary writers. Given the broad, synthetic nature of the work’s endeavour, individual writers/works are rarely discussed for longer than a page, and though G.’s commentary is always insightful, specialists on particular authors or social/historical trends will surely find much to work with and against here. -

Cahier De LECTURES - 2004 À 2018

Cahier de LECTURES - 2004 à 2018 Afrique : • « Ébène, aventures africaines» Ryszard Kapuscinski Pocket p 175 Un journaliste, amoureux de l'Afrique nous aide à comprendre ce continent • Africa Trek1 Sonia et Alexandre Poussin p 181 Un couple remonte l'Afrique à pied d'Afrique du sud à Jérusalem le tome 1 rend compte des 7000 km du sud de L'Afrique du Sud au Kilimandjaro (Tanzanie) • Dernières nouvelles de Françafrique vents d'ailleurs 2003 p 3 13 nouvelles d'auteurs africains qui traitent des rapports entre la France et l'Afrique suivi d'un hommage à Mongo Béti (Camerounais) par sa compagne qui parle de ses derniers moments. • Un fusil dans la main, un poème dans la poche Emmanuel Dongala Le serpent à plume 2003 p 3 • Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali Gil Courtemanche Boréal (Québec) p 3 • Petit Pays Gaël Faye Grasset 2016 II p • « Petit précis de remise à niveau sur l'histoire africaine à l'usage du président Sarkozy » sous la direction de Adame Ba Konaré p 108 En 2007, Sarkozy et ses conseillers, remplis des préjugés développés depuis « le temps béni des colonies », fait à Dakar un discours désastreux. Un certain nombre de chercheurs et spécialistes africains et autres cherchent à combler ses lacunes et nous aident à combler les nôtres. • « Togo, de l'esclavage au libéralisme mafieux » Gilles Labarth Agone p 103 • Les cigognes sont immortelles Alain Mabancou Seuil 2018 II p 81 Anarchie : voir commentaires • « L'anarchie, une histoire de révolte » Claude Faber Les Essentielles Milan p 20 Un livret de soixante pages. -

Piece List MARIA - Sophie Murk ACT I ACT II Look 1 - "Maria" Look 2 - "Act II Base" Look 3 - "2Nd FBI Agent" Look 4 - "Chart Hits"

Mr. Burns Piece List MARIA - Sophie Murk ACT I ACT II Look 1 - "Maria" Look 2 - "Act II Base" Look 3 - "2nd FBI Agent" Look 4 - "Chart Hits" Sweater RPT Socks RPT Socks REM Button Up Shirt Leggings RPT Necklace RPT Loafers REM Slacks/Suspenders Socks Dirty Tank Top RPT Tank Top REM Tie Keds Grey Dirty Leggings ADD Button Up Shirt ADD Feathered Hat Necklace Women's Loafers ADD Slacks Grey Dirty Leggings (UNDER) ADD Suspenders Dirty Tank Top (UNDER) ADD Tie Costume Designer: Lauren Rismiller Assistant Designer: Abby Shmidt 1 V. 4 Mr. Burns Piece List MATT - Micheal Ferguson Act I Act II Look 1 - "Matt" Look 2 - "Act II Base" Look 3 - "Chart Hits" Look 4 - "Homer" Flannel Plaid Shirt RPT Necklace ADD Beyonce Wig & Hat ADD OversiZed Polo Graphic T-Shirt RPT Socks ADD Beer Belly Pillow Kahki Shorts RPT Watch ADD Homer Helmet Socks RPT Wedding Band Canvas Sneakers Jeans Surfer Bro Necklace Bro Tank Sports Watch Men's Loafers Wedding Band Jean Jacket Bro Tank (UNDER) Costume Designer: Lauren Rismiller Assistant Designer: Abby Shmidt 2 V. 4 Mr. Burns Piece List SAM - Jacob Cange Act I Act II Look 1 - "Sam" Look 2 - "Act II Base" Look 3 - Chart Hits Look 4 - "Bart" Fitted Orange T-Shirt RPT Dirty Undershirt ADD Gaga Bustier REM Gaga Bustier Zip Up Hoodie RPT Socks ADD Uniform Jacket REM Uniform Jacket Loose Cargo Shorts RPT Watch ADD Gaga Wig REM Gaga Wig Converse Bart Shorts ADD Bart T-Shirt Watch Black Converse ADD Crown Belt Socks Dirty Undershirt (UNDER) Costume Designer: Lauren Rismiller Assistant Designer: Abby Shmidt 3 V. -

De L'autre Coté Du Periph': Les Lieux De L'identité Dans Le Roman Feminin

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France Mame Fatou Niang Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Niang, Mame Fatou, "De l'Autre Coté du Periph': Les Lieux de l'Identité dans le Roman Feminin de Banlieue en France" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1740. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1740 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DE L’AUTRE COTÉ DU PERIPH’ : LES LIEUX DE L’IDENTITÉ DANS LE ROMAN FEMININ DE BANLIEUE EN FRANCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of French Studies by Mame Fatou Niang Licence, Université Lyon 2 – 2005 Master 2, Université Lyon 2 –2008 August 2012 A Lissa ii REMERCIEMENTS Cette thèse n’aurait pu voir le jour sans le soutien de mon directeur de thèse Dr. Pius Ngandu Nkashama. Vos conseils et votre sourire en toute occasion ont été un véritable moteur. Merci pour toutes ces fois où je suis arrivée dans votre bureau sans rendez-vous, en vous demandant si vous aviez « 2 secondes » avant de m’engager dans des questions sans fin. -

Fitting Words Fit These Bingos Into Your Word Wardrobe: CLOTHES, FASHION, WEARABLES, ACCESSORIES Compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club

Fitting Words Fit these bingos into your word wardrobe: CLOTHES, FASHION, WEARABLES, ACCESSORIES compiled by Jacob Cohen, Asheville Scrabble Club A 8s ACOUSTIC ACCIOSTU hearing aid [n -S] AIGRETTE AEEGIRTT tuft of feathers worn as head ornament [n -S] ALGERINE AEEGILNR woolen fabric [n -S] APPLIQUE AEILPPQU to apply as decoration to larger surface [v -D, -ING, -S] APRONING AGINNOPR APRON, to provide with apron (garment worn to protect one's clothing) [v] ARMATURE AAEMRRTU to furnish with armor [v -D, -RING, -S] ARMGUARD ADGMNRRU covering to protect arm [n -S] ARMIGERO AEGIMORR armiger (one who carries armor of knight) [n -S] ARMORING AGIMNORR ARMOR, to furnish with armor (defensive covering) [v] ARMOURED ADEMORRU ARMOUR, to armor (to furnish with armor (defensive covering)) [v] ARMOURER AEMORRRU armorer (one that makes or repairs armor) [n -S] ATTIRING AGIINRTT ATTIRE, to clothe (to provide with clothing) [v] AVENTAIL AAEILNTV ventail (adjustable front of medieval helmet) [n -S] B 8s BABOUCHE ABBCEHOU heelless slipper [n -S] BABUSHKA AABBHKSU woman's scarf [n -S] BABYDOLL ABBDLLOY short sheer pajamas for women [n -S] BACKWRAP AABCKPRW wraparound garment that fastens in back [n -S] BAGGIEST ABEGGIST BAGGY, loose-fitting [adj] BALDRICK ABCDIKLR baldric (shoulder belt) [n -S] BALMORAL AABLLMOR type of shoe (covering for foot) [n -S] BANDANNA AAABDNNN large, colored handkerchief [n -S] BARATHEA AAABEHRT silk fabric [n -S] BAREHEAD AABDEEHR without hat [adv] BARENESS ABEENRSS state of being bare (naked (being without clothing or covering)) -

Cerita Sebuah Hati

Januari 2000 Harga Rp. 5000,00 Cerita Sebuah Hati Apakah aku gay? Bagaimanakah aku bisa kenal gay lain? Di manakah gay berkumpul di kotaku? Bagai manakah aku bisa memberitahu keluarga dan ka wan-kawan? Aku ingin punya pacar-bagaimanakah caranya? Keluargaku mendesak aku kawin-tolong! Pacarku kawin soma ceweq-1alu aku bagaimana? Bagaimanakah supaya aku tidak keno AIDS? Bagai manakah caranya main yang aman? Apakah mengi sap penis dan menelan sperma itu aman? Bagaima nakah cara mernakai kondom yang tepat? TELEPON SAJA HOTLINE G.N. (HO'TLINE GAY NASI01NAL) (031 ) 593 492'4 SENIN DAN JUMAT: PKL 03.00 SORE-09.00 MALAM W.I.B. Kerahasiaan dijamin! Di/ayani sesama gay! BUKU SERI • • ·a NUSANTARA N° 65 - JANUARI 2000 Penerbit: GAYo NUSAMARA (GN). GN terdiri dori: Awon; Dede Oetomo; lbhoed; Rajoso Mohordll<a; ldza/ !wan; Ruddy Mustapha; Suhortono. Alomot re Idoksl don sirkulasi: Jo/an Mulyosari Timur 46, Surabaya, Jo-Tim 60112, a, (03 l) : 593-4924, Fax (037) 599-3559, e-mail: <[email protected]>, homepage: http;// . welcome.to/goya. Horga eceron: Rp5.000,00. Hargo untuk kirimon per pos , (seluruh Indonesia): Rp6.IXXJ, 00. Rekenlng Bank: Bank Bali Cabang Pembontu Sutorejo, Surabaya, No. 29l-414-9323 (u.p, Dede Oetomo). Isl buku seri GA Ya NIJSANTARA belum tentu soma dengon pandongon organisosi GA Ya NUSAMA- · W\. Tercontumnyo noma otau foto seseorang dolam GA Ya NUSAMARA tidak menunjukkon seksualitas tertentu. Penerbit mengharapkan sumbangan tulisan don llustrasi yang bertemakan lesbian, goy don seksualitos alternatif lainnya. Penyumbong memperoleh 2 eksemplor nomor yang memuat sumbongannyo. SUmbongan yang tidak termuat hanyo okon dlkembalikon opabifa disertoi pe rangko baloson secukupnya. -

Disassociation, Co-Habitation, and Intrusion in French Literature’S Corporeal Spaces

EXILE’S SHIFTING NARRATIVE: DISASSOCIATION, CO-HABITATION, AND INTRUSION IN FRENCH LITERATURE’S CORPOREAL SPACES Angela Lynn Ritter A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies (French) in the School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Dominique Fisher Lydie Moudileno Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja Donald Reid Jessica Tanner © 2018 Angela Lynn Ritter ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Angela Lynn Ritter: Exile’s Shifting Narrative: Disassociation, Co-habitation, and Intrusion in French Literature’s Corporeal Spaces (Under the direction of Dominique Fisher) Migration has touched French-speaking countries and has inspired a large body of literature recounting migrant experiences in the francophone world. Much of the scholarship on this literature has focused on questions of exile and foreignness in relation to geographical border-crossing as well as on France’s policies toward immigrants in relation to philosophies of hospitality. Yet, authors are also thinking about “home” in ways that transcend geopolitical borders. My dissertation, “Exile’s Shifting Narrative: Disassociation, Co-habitation, and Intrusion in French Literature’s Corporeal Spaces,” examines a set of creative works that displace and theorize the politics of exile and of welcome in terms of the borders of the human body. Considering contemporary French and francophone literature, performance, and film by authors Claire Denis, Wajdi Mouawad, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Marie NDiaye whose works are linked through their staging of dispossessed bodies, my dissertation offers a reconsideration of what it means to have or own a body, demonstrates the blurred boundaries between the Self and the Other, and reveals the possibility of being exiled from one’s own body or to someone else’s body. -

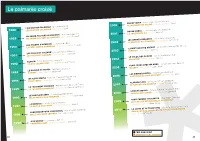

Le Palmarès Croisé

Le palmarès croisé 1988 L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) INGRID CAVEN - Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Gallimard) L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) 2000 ALLAH N’EST PAS OBLIGÉ - Ahmadou Kourouma (Seuil) UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) ROUGE BRÉSIL - Jean-Christophe Rufin (Gallimard) 1989 UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) 2001 LA JOUEUSE DE GO - Shan Sa (Grasset) LES CHAMPS D’HONNEUR - Jean Rouaud (Minuit) LES OMBRES ERRANTES - Pascal Quignard (Grasset) 1990 LE PETIT PRINCE CANNIBALE - Françoise Lefèvre (Actes Sud) 2002 LA MORT DU ROI TSONGOR - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) 1991 LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) LA MAÎTRESSE DE BRECHT - Jacques-Pierre Amette (Albin Michel) LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) 2003 FARRAGO - Yann Apperry (Grasset) TEXACO - Patrick Chamoiseau (Gallimard) 1992 LE SOLEIL DES SCORTA - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) L’ÎLE DU LÉZARD VERT - Edouardo Manet (Flammarion) 2004 UN SECRET - Philippe Grimbert (Grasset) 1993 LE ROCHER DE TANIOS - Amin Maalouf (Grasset) TROIS JOURS CHEZ MA MÈRE - François Weyergans (Grasset) CANINES - Anne Wiazemsky (Gallimard) 2005 MAGNUS - Sylvie Germain (Albin Michel) 1994 UN ALLER SIMPLE - Didier Van Cauwelaert (Albin Michel) LES BIENVEILLANTES - Jonathan Littell (Gallimard) BELLE-MÈRE - Claude Pujade-Renaud (Actes Sud) 2006 CONTOURS DU JOUR QUI VIENT - Léonora Miano (Plon) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS - Andreï Makine (Mercure de France) 1995 ALABAMA SONG - Gilles Leroy (Mercure de France) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS