University of Hradec Králové Philosophical Faculty Department of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Brigid Guides Our Way Through the Light and Darkness of Our Time

y ISSUE 27 VOLUME 2 Proudly Serving Celts in North America Since 1991 FEBRUARY 2018 Brigid Guides our Way Through the Light and Darkness of our Time By CYNTHIA WALLENTINE HETHER we are ready or not, no season W arrives without AS BREXIT ‘cliff-edge’ fears grow, a forecast prepared for the change of some kind. The British Government and leaked by news website BuzzFeed re- portedly says the economy will be worse off after the country real question is whether leaves the European Union, regardless of what trade deal is the change is welcomed as struck with the bloc. It is scheduled to depart at 11 PM UK time growth or blunt require- on Friday, March, 29, 2019. [Read more inside on page 8] ment. With the passage of the Festi- val of Imbolg in early Febru- ary, we are now in the season of light, the territory of the great Celtic goddess Brigid. With a legacy that stretches from the prehistoric tribes of Europe to refined Christian cathedrals cen- turies later, the goddess withstands time. In his work, The Festival of Brigit, Irish author Seamus O’ Cathain writes “that Brigit, whose very name embod- ies the concept of growth, should have remained such a constant icon of ven- IMAGE: Brigid by tattereddreams on DeviantArt. eration for heathen and Christian Celt March 1 is St. David’s Day, the national day of Wales, and alike.” way, others turn to the vague leanings new energy. Whether your tool is a pen, celebrated by Welsh around the world. [Read more page 6] At Imbolg, the load of winter lightens. -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Party Organisation and Party Adaptation: Western European Communist and Successor Parties Daniel James Keith UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April, 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature :……………………………………… iii Acknowledgements My colleagues at the Sussex European Institute (SEI) and the Department of Politics and Contemporary European Studies have contributed a wealth of ideas that contributed to this study of Communist parties in Western Europe. Their support, generosity, assistance and wealth of knowledge about political parties made the SEI a fantastic place to conduct my doctoral research. I would like to thank all those at SEI who have given me so many opportunities and who helped to make this research possible including: Paul Webb, Paul Taggart, Aleks Szczerbiak, Francis McGowan, James Hampshire, Lucia Quaglia, Pontus Odmalm and Sally Marthaler. -

Supply of the Register of Electors 2021 (Pdf 138KB)

Supply of the Register of Electors 2021 The full list of all persons and organisations supplied with a copy of the Register of Electors between 01 December 2020 - 30 November 2021. L ondon Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham If you have any comments or questions please contact: Clancy Connolly Electoral Services Officer [email protected] 02 August 2021 Version of Area(s) Party/Organisation Register Price Register/Updates Requested 01 December 2020 Hammersmith & Fulham Free Statutory Register & monthly Councillor's Ward Councillors Full Register Requirement updates. Only 01 December 2020 Hammersmith & Fulham Free Statutory Register & monthly Libraries Open Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Free Statutory Register & monthly Liberal Democrats Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Register, Overseas voters list, postal Free Statutory voters list & monthly Labour Party Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Register, Overseas voters list, postal Free Statutory voters list & monthly Conservative Party Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Register, Overseas Free Statutory voters list & monthly Greg Hands MP Full Register Requirement updates. Fulham Wards 01 December 2020 Register, Overseas Free Statutory voters list & monthly Hammersmith Andrew Slaughter MP Full Register Requirement updates. Wards 01 December 2020 Free Statutory Register & monthly Hammersmith Labour Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Register, Overseas Free Statutory voters list & monthly H&F Liberal Democrats Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Free Statutory Register & monthly Women's Equality Party Full Register Requirement updates. Whole Borough 01 December 2020 Free Statutory Register & monthly Green Party Full Register Requirement updates. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2013

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set, 1960-2013 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET 1960-2013 Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2013 (CPDS) is a collection of political and institu- tional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Hand- lungsspielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” directed by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member coun- tries for the period of 1960 to 2013. In all countries, political data were collected only for the democratic periods.1 The data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time- series analyses. The present data set combines and replaces the earlier versions “Comparative Political Data Set I” (data for 23 OECD countries from 1960 onwards) and the “Comparative Political Data Set III” (data for 36 OECD and/or EU member states from 1990 onwards). A variable has been added to identify former CPDS I countries. For additional detailed information on the composition of government in the 36 countries, please consult the “Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Com- position 1960-2013”, available on the CPDS website. The Comparative Political Data Set contains some additional demographic, socio- and eco- nomic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD, Eurostat or AMECO. -

The Czech Republic Is a Landlocked State Located in Central Europe Covering an Area of 30,450 Square Miles (78,866 Square Kilometres)

CZECH REPUBLIC COUNTRY ASSESSMENT APRIL 2002 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM CONTENTS I. Scope of document 1.1 - 1.5 II. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 Economy 2.3 - 2.6 III. History 3.1 - 3.14 IV. State Structures The Constitution 4.1 Political System 4.2 - 4.12 Judiciary 4.13 - 4.14 Military 4.15 - 4.17 Internal Security 4.18 - 4.19 Legal Rights/Detention 4.20 - 4.24 Prison 4.25 Medical Service 4.26 - 4.28 Education System 4.29 V. Human Rights V.A. Human Rights Issues Overview 5.1 - 5.16 Freedom of Speech 5.17 - 5.26 Freedom of Religion 5.27 - 5.30 Freedom of Assembly & Association 5.31 - 5.34 Employment Rights 5.35 - 5.37 People Trafficking 5.38 - 5.40 Freedom of Movement 5.41 - 5.44 V.B. Human Rights - Specific Groups Women 5.45 - 5.51 Children 5.52 - 5.54 Roma 5.55 - 5.161 Conscientious Objectors & Deserters 5.162 Homosexuals 5.163. - 5.169 Political Activists 5.170 Journalists 5.171 Prison Conditions 5.172 V.C. Human Rights - Other Issues Citizenship 5.173 People with Disabilities 5.174 Annexes ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX C: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS BIBLIOGRAPHY I. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. -

Journals Muni Cz

Středoevropské politické studie / Central European Political Studies Review, ISSN 1212-7817 Ročník XVI, Číslo 1, s. 75–92 / Volume XVI, Issue 1, pp. 75–92 DOI: 10.5817/CEPSR.2014.1.75 (c) Mezinárodní politologický ústav / International Institute of Political Science Strana svobodných občanů – čeští monotematičtí euroskeptici?1 Petr Kaniok Abstract: The Party of Free Citizens: A Czech Single Issue Eurosceptic Party? When, in the beginning of 2009, the Party of Free Citizens was founded, it was believed that the main impulse for establishing a new political party was the generally positive approach towards the Lisbon Treaty adopted by the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) a couple of months before. Thus, since its foundation, the media, commentators and political analysts have labelled the Party of Free Citizens as a single issue Eurosceptic party. This article challenges this prevailing evaluation of the Party of Free Citizens and subsequently confronts the party´s programs and press releases with three concepts – the concept of Euroscepticism connected with the work of Taggart and Szczerbiak, the concept of a single issue party developed by Mudde, and the concept of a niche party brought into political science by Meguide. The article concludes that while the Party of Free Citizens is undoubtedly a Eurosceptic party, both in terms of its soft and hard versions, its overall performance as a political entity does not meet the criteria of Mudde´s concept of a single issue party. As the Party of Free Citizens puts a strong emphasis on European issues (compared to other mainstream Czech political parties), it can, at most, be described as a niche party. -

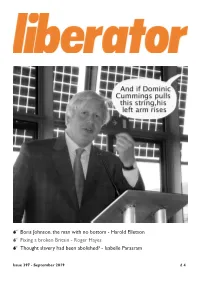

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

International Conference Education and Language Edition

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE EDUCATION AND LANGUAGE EDITION 19 AUGUST 2019 Novotel, Athens, Greece CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS BOOK 1 | VOLUME 2 EDUCATION AND EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS DISCLAIMER This book contains abstracts, keywords and full papers, which has gone under double blind peer-review by NORDSCI Review Committee. Authors of the articles are responsible for the content and accuracy. The book covers the scientific sections Education and Educational research, Language and Linguistics. Opinions expressed might not necessary affect the position of NORDSCI Committee Members and Scientific Council. Information in the NORDSCI 2019 Conference proceedings is subject to change without any prior notice. No parts of this book can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any mean without the written confirmation of the Scientific Council of NORDSCI. Copyright © NORDSCI 2019 All right reserved by NORDSCI International Conference Published by SAIMA CONSULT LTD, Sofia, Bulgaria Total print 60 ISSN 2603-4107 ISBN 978-619-7495-05-8 DOI 10.32008/NORDSCI2019/B1/V2 NORDSCI CONFERENCE Contact person: Maria Nikolcheva e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nordsci.org SCIENTIFIC PARTNERS OF NORDSCI INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE EUROPEAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, ARTS AND LETTERS SLOVAK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES CZECH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF UKRAINE BULGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF HUNGARY SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES TURKISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA ISLAMIC WORLD ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LATVIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ABAY KAIRZHANOV, RUSSIA LAURA PRICOP, ROMANIA ALEXANDER IVANOV, RUSSIA DOROTA ORTENBURGER, POLAND CHIRCU SORINA, ROMANIA JONAS JAKAITIS, LITHUANIA ELENI HADJIKAKOU, GREECE MAGDALENA BALICA, ROMANIA JANA WALDNEROVA, SLOVAKIA TABLE OF CONTENTS Section EDUCATION AND EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH | 1. -

Of European and National Election Results Update: September 2018

REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2018 A Public Opinion Monitoring Publication REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2018 Directorate-General for Communication Public Opinion Monitoring Unit September 2018 - PE 625.195 TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 1. COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 5 DISTRIBUTION OF SEATS EE2019 6 OVERVIEW 1979 - 2014 7 COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LAST UPDATE (10/09/2018) 8 CONSTITUTIVE SESSION (01/07/2014) 9 PROPORTION OF WOMEN AND MEN PROPORTION - LAST UPDATE 10 PROPORTIONS IN POLITICAL GROUPS - LAST UPDATE 11 PROPORTION OF WOMEN IN POLITICAL GROUPS - SINCE 1979 12 2. NUMBER OF NATIONAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 13 3. TURNOUT: EE2014 15 TURNOUT IN THE LAST EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTIONS 16 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 18 TURNOUT COMPARISON: 2009 (2013) - 2014 19 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 - BREAKDOWN BY GENDER 20 TURNOUT IN THE EE2014 - BREAKDOWN BY AGE 21 TURNOUT OVERVIEW SINCE 1979 22 TURNOUT OVERVIEW SINCE 1979 - BY MEMBER STATE 23 4. NATIONAL RESULTS BY MEMBER STATE 27-301 GOVERNMENTS AND OPPOSITION IN MEMBER STATES 28 COMPOSITION OF THE EP: 2014 AND LATEST UPDATE POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE EP MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT - BY MEMBER STATE EE2014 TOTAL RESULTS EE2014 ELECTORAL LISTS - BY MEMBER STATE RESULTS OF TWO LAST NATIONAL ELECTIONS AND THE EE 2014 DIRECT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS SOURCES EDITORIAL First published in November 2014, the Review of European and National Elections offers a comprehensive, detailed and up-to-date overview on the composition of the European Parliament, national elections in all EU Member States as well as a historical overview on the now nearly forty years of direct elections to the European Parliament since 1979. -

This Document Does Not Meet the Current Format Guidelines of The

DISCLAIMER: This document does not meet current format guidelines Graduate School at the The University of Texas at Austin. of the It has been published for informational use only. Copyright by Kathryn Quinn O’Dowd 2017 The Thesis committee for Kathryn Quinn O’Dowd Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Beyond the Spectrum: Understanding Czech Euroscepticism Outside Left- Right Classification APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: ______________________________________ Rachel Wellhausen, Supervisor __________________________________________ Mary Neuburger Beyond the Spectrum: Understanding Czech Euroscepticism Outside Left- Right Classification By Kathryn Quinn O’Dowd, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2017 Acknowledgements There are so many people who have aided in the thesis writing process. First, thank you to all of the professors that I have had over the years, whose courses have either directly or indirectly influenced the development of this work. The office staff at the Center for Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies- especially Roy Flores, Jenica Jones, and Agnes Sekowski- have been an enormous support. Christian Hilchey, thank you for your Czech instruction over the last two years. Martin thank you for your advice on how to conduct research in the Czech Republic, as well as connecting me with many of the researched parties. Mary Neuburger, thank you for reading my drafts and providing feedback throughout the process. Most importantly I need to thank my advisor Rachel Wellhausen, without whose guidance this project would have failed miserably.