Appendix V4b: Community Building Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oahu Processing Centers Kauai Processing Centers

State of Hawaii Processing Centers Office Hours: 7:45 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Oahu Processing Centers Kauai Processing Centers Kapolei Processing Center (250) Kauai Processing Center East 601 Kamokila Boulevard, Room 117 Former Lihue Courthouse Building Kapolei, HI 96707 3059 Umi Street, Room A110 Phone: 692-8384 Fax: 692-7783 Lihue, HI 96766 Phone: 808-274-3371 Koolau Processing Center (306) & Fax: 808-335-8446 (390) Waikalua (306) Maui County Processing Centers 45-260 Waikalua Road Kaneohe, HI 96744 Maui Public Assistance (777) Phone: 233-3621 Fax: 233-3620 State Building 54 High St. #125 Luluku (390) Wailuku, HI 96793 45-513 Luluku Road Phone: 808-984-8300 Kaneohe, HI 96744 Fax: 808-984-8333 Phone: 233-5325 Fax: 233-5358 Molokai Unit (852) KPT Processing Center (160) 55 Makaena Pl. Rm. 1 1485 Linapuni Street, Suite 122 Kaunakakai, HI 96748 Honolulu, HI 96819 Phone: 808-553-1715 Phone: 832-3800 Fax: 832-3392 Fax: 808-553-1720 OR&L Processing Center (170) Mailing Address: 333 North King Street, Room 200 PO Box 70, Honolulu, HI 96817 Kaunakakai, HI 96748 Phone: 586-8047 Fax: 586-8138 Lanai Sub-Unit (853) Pohulani Processing Center (370) 730 Lanai Avenue 677 Queen Street, Suite 400B Lanai City, HI 96763 Honolulu, HI 96813 Phone: 808-565-7102 Phone: 587-5283 Fax: 587-5297 Fax: 808-565-6460 Wahiawa Processing Center (290) Mailing Address: 929 Center Street PO Box 631374 Wahiawa, HI 96786 Lanai City, HI 96763 Phone: 622-6315 Fax: 622-6484 Waianae Processing Center (270) 86-120 Farrington Highway, Suite A103 Waianae, HI 96792 Phone: 697-7881 Fax: 697-7184 Waipahu Processing Center (190) 94-275 Mokuola Street, Room 303A Waipahu, HI 96797 Phone: 675-0052 Fax: 675-0038 03/2018 State of Hawaii Processing Centers Office Hours: 7:45 a.m. -

Hale Ho′Ola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy

Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy June 2013 Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy Prepared by: Gerald A. Doeksen, Director Email: [email protected] and Cheryl St. Clair, Associate Director Email: [email protected] National Center for Rural Health Works Oklahoma State University Phone: 405-744-6083 R. Scott Daniels, Performance Improvement/Flex Coordinator Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-961-9460 and Gregg Kishaba, Rural Health Coordinator Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-586-5446 Hawaii State Department of Health State Office of Primary Care & Rural Health Deborah Birkmire-Peters, Program Director Pacific Basin Telehealth Resource Center John A. Burns School of Medicine University of Hawaii at Manoa Email: [email protected] Phone: 808-692-1090 June 2013 Hale Hoola Hamakua Community Health Needs Assessment Summary and Implementation Strategy Table of Contents I. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. Overview of Process ......................................................................................................... 2 III. Participants, Facilitators, and Medical Service Area ........................................................ 3 IV. About Hale Hoola Hamakua ............................................................................................ 7 V. Community Input Summary ............................................................................................ -

Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015

STATEWIDE COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2015 Department of Land & Natural Resources ii Hawai‘i Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015 Update PREFACE The Hawai‘i State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2015 Update is prepared in conformance with a basic requirement to qualify for continuous receipt of federal grants for outdoor recreation projects under the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act, Public Law 88-758, as amended. Through this program, the State of Hawai‘i and its four counties have received more than $38 million in federal grants since inception of the program in 1964. The Department of Land and Natural Resources has the authority to represent and act for the State in dealing with the Secretary of the Interior for purposes of the LWCF Act of 1965, as amended, and has taken the lead in preparing this SCORP document with the participation of other state, federal, and county agencies, and members of the public. The SCORP represents a balanced program of acquiring, developing, conserving, using, and managing Hawai‘i’s recreation resources. This document employs Hawaiian words in lieu of English in those instances where the Hawaiian words are the predominant vernacular or when there is no English substitute. Upon a Hawaiian word’s first appearance in this plan, an explanation is provided. Every effort was made to correctly spell Hawaiian words and place names. As such, two diacritical marks, ‘okina (a glottal stop) and kahakō (macron) are used throughout this plan. The primary references for Hawaiian place names in this plan are the book Place Names of Hawai‘i (Pukui, 1974) and the Hawai‘i Board on Geographic Names (State of Hawai‘i Office of Planning, 2014). -

Inventory and Initial Screening Report

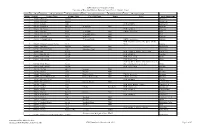

COUNTY OF HAWAII MASS TRANSIT AGENCY BUS STOP LOCATION STUDY INVENTORY AND INITIAL SCREENING REPORT Prepared by: SSFM International, Inc. 501 Sumner Street, Suite 620 Honolulu, HI 96817 Prepared for: County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency 630 E. Lanikaula Street Hilo, HI 96720 June 2010 Bus Stop Location Project for County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency Inventory and Initial Screening Report Introduction County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency Bus Stop Location Project Inventory and Initial Screening Report I. Introduction The County of Hawaii Mass Transit Agency (MTA) currently operates on a flagstop basis. With increased usage and traffic, MTA is moving into a designated bus stop program. SSFM International, Inc. (SSFM) was contracted to identify locations for bus stops islandwide and to determine if locations warrant an official bus stop listed in the Hawaii County Code. Official bus stops will need to be Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant. This Inventory and Initial Screening Report constitutes the deliverable for Task One of the work program for this study. Based on field work conducted and meetings held with bus drivers, SSFM developed a complete inventory of bus stops islandwide. The inventory, consisting of approximately 575 stops, was then divided into priority and non-priority stops for the remainder of the work tasks in this study. Priority stops, totaling approximately 100 stops, were recommended based on surrounding land use, frequency, and local knowledge. The list of priority stops is shown in (Appendix 1). These stops handle the bulk of the ridership and are in close vicinity to schools, resorts, medical facilities, and urban centers. -

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island Status Key: 1 = Not Hawaiian; 2 = Not Reviewed; 3 = More Research Needed; 4 = HBGN Corrected; 5 = Already Correct in GNIS; 6 = Name Change Status Feat ID Feature Name Feature Class Corrected Name Source Notes USGS Quad Name 1 365008 1940 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 1 365009 1949 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 3 358404 Aa Falls Falls PNH: not listed Kukuihaele 5 358406 ʻAʻahuwela Summit ‘A‘ahuwela PNH Puaakala 3 358412 Aale Stream Stream PNH: not listed Piihonua 4 358413 Aamakao Civil ‘A‘amakāō PNH HBGN: associative Hawi 4 358414 Aamakao Gulch Valley ‘A‘amakāō Gulch PNH Hawi 5 358415 ʻĀʻāmanu Civil ‘Ā‘āmanu PNH Kukaiau 5 358416 ʻĀʻāmanu Gulch Valley ‘Ā‘āmanu Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Kukaiau PNH: Ahalanui, not listed, Laepao‘o; Oneloa, 3 358430 Ahalanui Laepaoo Oneloa Civil Maui Kapoho 4 358433 Ahinahena Summit ‘Āhinahina PNH Puuanahulu 5 1905282 ʻĀhinahina Point Cape ‘Āhinahina Point PNH Honaunau 3 365044 Ahiu Valley PNH: not listed; HBGN: ‘Āhiu in HD Kau Desert 3 358434 Ahoa Stream Stream PNH: not listed Papaaloa 3 365063 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Pahala 3 1905283 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Milolii PNH: not listed; HBGN: Āholehōlua if it is the 3 1905284 ʻĀhole Holua Locale slide, Āholeholua if not the slide Milolii 3 358436 Āhole Stream Stream PNH: Āhole, Maui Papaaloa 4 358438 Ahu Noa Summit Ahumoa PNH Hawi 4 358442 Ahualoa Civil Āhualoa PNH Honokaa 4 358443 Ahualoa Gulch Valley Āhualoa Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Honokaa -

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, Died Feb. 8, 1993. He

SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Survived by wife, Lourdes S.; daughters, Mrs. Domi (Rose) Timbresa and Mrs. Robert (Carmen) McDonald; six grandchildren; sister, Teresa of the Philippines; nieces and nephews. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortaury; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. [Honolulu Advertiser 16 February 1993] SABADO, VENTURA NONEZA, 83, of Honolulu, died Feb. 8, 1993. He was born in Luna, La Union, Philippines, and was formerly employed as a tailor at Andrade’s and Ross Sutherland. Friends may call from 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortuary; service 7 p.m. Mass 9:45 a.m. Saturday at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Burial at Diamond Head Memorial Park. Aloha attire. A recent obituary was incomplete. [Honolulu Advertiser 17 February 1993] Saballus, Doriel L., of Honolulu died last Thursday in St. Francis Hospital. Saballus, 46, was born in Berkeley, Calif. She is survived by husband Klaus; daughter Stephanie; parents Leo and Charlene Dwyer; and sister Leslie Dwyer. Services: 3 p.m. Saturday at Borthwick Mortuary. Calla after 2:30 p.m. Casual attire. No flowers. Memorial donations suggested to St. Francis Hospice. [Honolulu Star-Bulletin 7 January 1993] SABALLUS, DORIEL LEA, 46, of Honolulu, died Dec. 31, 1992. She was born in Berkeley, Calif. Survived by husband, Klaus; daughter, Stephanie; parents, Leo and Charlene Dwyer; sister, Leslie Dwyer; a nephew; au aunt. -

General Plan for the County of Hawai'i

COUNTY OF HAWAI‘I GENERAL PLAN February 2005 Pursuant Ord. No. 05-025 (Amended December 2006 by Ord. No. 06-153, May 2007 by Ord. No. 07-070, December 2009 by Ord. No. 09-150 and 09-161, June 2012 by Ord. No. 12-089, and June 2014 by Ord. No. 14-087) Supp. 1 (Ord. No. 06-153) CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose Of The General Plan . 1-1 1.2. History Of The Plan . 1-1 1.3. General Plan Program . 1-3 1.4. The Current General Plan Comprehensive Review Program. 1-4 1.5. County Profile. 1-7 1.6. Statement Of Assumptions. 1-11 1.7. Employment And Population Projections . 1-12 1.7.1. Series A . 1-13 1.7.2. Series B . 1-14 1.7.3. Series C . 1-15 1.8. Population Distribution . 1-17 2: ECONOMIC 2.1. Introduction And Analysis. 2-1 2.2. Goals . .. 2-12 2.3. Policies . .. 2-13 2.4. Districts. 2-15 2.4.1. Puna . 2-15 2.4.2. South Hilo . 2-17 2.4.3. North Hilo. 2-19 2.4.4. Hamakua . 2-20 2.4.5. North Kohala . 2-22 2.4.6. South Kohala . 2-23 2.4.7. North Kona . 2-25 2.4.8. South Kona. 2-28 2.4.9. Ka'u. 2-29 3: ENERGY 3.1. Introduction And Analysis. 3-1 3.2. Goals . 3-8 3.3. Policies . 3-9 3.4. Standards . 3-9 4: ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4.1. Introduction And Analysis. -

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30,1955

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 395 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 395 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII By E. G. Bailey Washington, D. C., 1956 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 HAWAII By E. G. Bailey EXPLANATION This Index lists the streamflow and reservoir stations In Hawaii for which records have been or are to be published In reports of the Geological Survey for periods prior to September 30, 1955. The stations are listed In the downstream order. Starting at the headwater of each stream all stations are listed In a downstream direction. Tributary streams are Indicated by Indention and are Inserted between main-stem stations In the order In which they enter the main stream. To indicate the rank of any tributary on which a record is available and the stream to which it is immediately tributary, each indention in the listing of stations represents one rank. A stream name only is inserted where necessary for the purpose of showing the proper rank or order of tributaries. Station names are given in their most recently published forms. Parentheses around part of a station name indicate that the enclosed word or words were used in an earlier published name of the station or in a name under which records were published by some agency other than the Geological Survey. -

General Plan for the County of Hawai'i

COUNTY OF HAWAI‘I GENERAL PLAN February 2005 Pursuant Ord. No. 05-025 (Amended December 2006 by Ord. No. 06-153, May 2007 by Ord. No. 07-070, December 2009 by Ord. No. 09-150 and 09-161, and June 2012 by Ord. No. 12-089) Supp. 1 (Ord. No. 06-153) CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1. Purpose Of The General Plan . 1-1 1.2. History Of The Plan . 1-1 1.3. General Plan Program . 1-3 1.4. The Current General Plan Comprehensive Review Program. 1-4 1.5. County Profile. 1-7 1.6. Statement Of Assumptions. 1-11 1.7. Employment And Population Projections . 1-12 1.7.1. Series A . 1-13 1.7.2. Series B . 1-14 1.7.3. Series C . 1-15 1.8. Population Distribution . 1-17 2: ECONOMIC 2.1. Introduction And Analysis. 2-1 2.2. Goals . .. 2-12 2.3. Policies . .. 2-13 2.4. Districts. 2-15 2.4.1. Puna . 2-15 2.4.2. South Hilo . 2-17 2.4.3. North Hilo. 2-19 2.4.4. Hamakua . 2-20 2.4.5. North Kohala . 2-22 2.4.6. South Kohala . 2-23 2.4.7. North Kona . 2-25 2.4.8. South Kona. 2-28 2.4.9. Ka'u. 2-29 3: ENERGY 3.1. Introduction And Analysis. 3-1 3.2. Goals . 3-8 3.3. Policies . 3-9 3.4. Standards . 3-9 4: ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY 4.1. Introduction And Analysis. 4-1 4.2. Goals . -

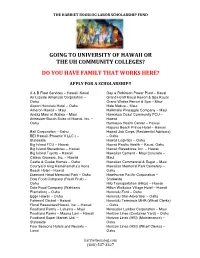

Going to University of Hawaii Or the Uh Community Colleges?

THE HARRIET BOUSLOG LABOR SCHOLARSHIP FUND GOING TO UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII OR THE UH COMMUNITY COLLEGES? DO YOU HAVE FAMILY THAT WORKS HERE? APPLY FOR A SCHOLARSHIP!! A & B Fleet Services – Hawaii, Kauai Gay & Robinson Power Plant – Kauai Air Liquide American Corporation – Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort & Spa Kauai Oahu Grand Wailea Resort & Spa – Maui Airport Honolulu Hotel – Oahu Hale Makua – Maui Ameron Hawaii – Maui Haliimaile Pineapple Company – Maui Andaz Maui at Wailea – Maui Hamakua Coast Community FCU – Anheuser-Busch Sales of Hawaii, Inc. – Hawaii Oahu Hamakua Health Center – Hawaii Hapuna Beach Prince Hotel – Hawaii Ball Corporation – Oahu Hawaii Job Corps (Residential Advisors) BEI Hawaii (Phoenix V LLC.) – – Oahu Statewide Hawaii Logistics – Oahu Big Island FCU – Hawaii Hawaii Pacific Health – Kauai, Oahu Big Island Stevedores – Hawaii Hawaii Stevedores, Inc. – Hawaii Big Island Toyota – Hawaii Hawaiian Cement – Maui Concrete – Calavo Growers, Inc. – Hawaii Maui Castle & Cooke Homes – Oahu Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar – Maui Courtyard King Kamehameha’s Kona Hawaiian Memorial Park Cemetery – Beach Hotel – Hawaii Oahu Diamond Head Memorial Park – Oahu Hawthorne Pacific Corporation – Dole Food Company (Fresh Fruit) – Statewide Oahu Hilo Transportation (Hitco) – Hawaii Dole Food Company (Wahiawa Hilton Waikoloa Village Hotel – Hawaii Plantation) – Oahu Honolulu Ford – Oahu Eggs Hawaii – Oahu Honolulu Star-Advertiser – Oahu Fairmont Orchid – Hawaii Honolulu Terminals MHR (Wharf Clerks) Floral Resources/Hawaii, Inc. – Hawaii – Oahu Foodland -

Entomological Society

ISSN 0073-134X PROCEEDINGS of the HAWAIIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY This Issue Dedicated to Edwin H. Bryan, Jr. Vol. 26 March 1,1986 PROCEEDINGS of the Hawaiian Entomological Society VOLUME 26 FOR THE YEAR 1984 MARCH 1, 1986 The following minutes, notes and exhibitions were recorded by the Secretary on the months indicated during the calandar year 1984. The minutes as they appear here contain only the highlights in abbreviated form with attendance totals only. Complete minutes can be obtained from the Secretary's files. The Editor. JANUARY The 937 th meeting of the Hawaiian Entomological Society was called to order by Pres. Barry Brennan at 2:05 p.m., January 9, 1984 in the Conference room of the Bishop Museum. Fourteen members were present. Old Business: Brennan read a letter from Elwood Zimmerman as a reply to a congratulatory letter from the HES, on the occasion of Zimmerman's receiving of the Jordan Medal. In the letter he noted that the Insects of Hawaii Volumes that he had been working on could not be completed. A lively discussion followed. New Business: JoAnn Tenorio brought some old photos of Entomological Society members as a supplement to her presidential address in December. No notes or exhibitions were submitted. Announcements: Pres. Brennan announced that rather than voting on amend ments suggested by the previous constitution committee, a new committee will be appointed and the recommendations of both committees will be considered simul taneously in the future. Wallace Mitchell announced a public meeting to be held Jan. 17th and 18th to discuss the tri-fly eradication program. -

Appendix V4c: Local Economic Development Analysis

1 APPENDIX V4C: LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ANALYSIS 2 Introduction 3 Purpose 4 This appendix summarizes the background information that informs consideration of alternative 5 strategies for building a robust local economy. Those strategies that are best aligned with Hāmākua’s 6 Community Objectives and most feasible will be included in CDP Chapter IV3: “Build a Robust Local 7 Economy.” 8 Importantly, this appendix is NOT the Hāmākua CDP – it does not establish policy or identify plans of 9 action. Instead, for issues related to local economic development, including agriculture, renewable 10 energy, ecosystem services, the health care industry, the education field, the visitor industry, retail, this 11 appendix does four things: 12 . Outlines existing policy, especially County policy established in the General Plan; 13 . Summarizes related, past planning and studies; 14 . Introduces alternative strategies available to achieve Hāmākua’s community objectives; 15 . Preliminarily identifies feasible strategy directions. 16 In other words, this appendix sets the context for identifying preferred CDP strategies. Existing policy 17 provides the framework in which the CDP is operating, related plans identify complementary initiatives, 18 and alternative strategies introduce the “tool box” from which the CDP can choose the best tools for the 19 CDP Planning Area. 20 This appendix complements Appendices V4A and V4B, which focus on natural and cultural resource 21 management and community building, respectively. In those appendices, issues related to but distinct 22 from economic development are discussed in greater detail, including the preservation of open space 23 and agricultural land, historic preservation, watershed and coastal management, access and trails, 24 cultural centers, land use regulations, infrastructure, housing, human services, schools, parks, and 25 community-based, collaborative action.