CONTROL NUMBER 27. W ' Cu-.1.SSJT:ON(€S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZAPOTE the Popular Name Represents Many Diverse Edible Fruits of Guatemala

Sacred Animals and Exotic Tropical Plants monzón sofía photo: by Dr. Nicholas M. Hellmuth and Daniela Da’Costa Franco, FLAAR Reports ZAPOTE The popular name represents many diverse edible fruits of Guatemala ne of the tree fruits raised by the Most zapotes have a soft fruit inside and Maya long ago that is still enjoyed a “zapote brown” covering outside (except today is the zapote. Although for a few that have other external colors). It Othere are several fruits of the same name, the is typical for Spanish nomenclature of fruits popular nomenclature is pure chaos. Some of and flowers to be totally confusing. Zapote is the “zapote” fruits belong to the sapotaceae a vestige of the Nahuatl (Aztec) word tzapotl. family and all are native to Mesoamerica. The first plant on our list, Manilkara But other botanically unrelated fruits are also zapote, is commonly named chicozapote. called zapote/sapote; some are barely edible This is one of the most appreciated edible (such as the zapotón). There are probably species because of its commercial value. It even other zapote-named fruits that are not is distributed from the southeast of Mexico, all native to Mesoamerica. especially the Yucatán Peninsula into Belize 60 Dining ❬ ANTIGUA and the Petén area, where it is occasionally now collecting pertinent information related an abundant tree in the forest. The principal to the eating habits of Maya people, and all products of these trees are the fruit; the the plants they used and how they used them latex, which is used as the basis of natural for food. -

Method to Estimate Dry-Kiln Schedules and Species Groupings: Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Method to Estimate Forest Service Forest Dry-Kiln Schedules Products Laboratory Research and Species Groupings Paper FPL–RP–548 Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods William T. Simpson Abstract Contents Dry-kiln schedules have been developed for many wood Page species. However, one problem is that many, especially tropical species, have no recommended schedule. Another Introduction................................................................1 problem in drying tropical species is the lack of a way to Estimation of Kiln Schedules.........................................1 group them when it is impractical to fill a kiln with a single Background .............................................................1 species. This report investigates the possibility of estimating kiln schedules and grouping species for drying using basic Related Research...................................................1 specific gravity as the primary variable for prediction and grouping. In this study, kiln schedules were estimated by Current Kiln Schedules ..........................................1 establishing least squares relationships between schedule Method of Schedule Estimation...................................2 parameters and basic specific gravity. These relationships were then applied to estimate schedules for 3,237 species Estimation of Initial Conditions ..............................2 from Africa, Asia and Oceana, and Latin America. Nine drying groups were established, based on intervals of specific Estimation -

An Ethnographicsurvey

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 186 Anthropological Papers, No. 65 THE WARIHIO INDIANS OF SONORA-CHIHUAHUA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY By Howard Scott Gentry 61 623-738—63- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 65 Introduction 69 Informants and acknowledgments 69 Nominal note 71 Peoples of the Rio Mayo and Warihio distribution 73 Habitat 78 Arroyos 78 Canyon features 79 Hills 79 Cliffs 80 Sierra features - 80 Plants utilized 82 Cultivated plants 82 Wild plants 89 Root and herbage foods 89 Seed foods 92 Fruits 94 Construction and fuel 96 Medicinal and miscellaneous uses 99 Use of animals 105 Domestic animals 105 Wild animals and methods of capture 106 Division of labor 108 Shelter 109 Granaries 110 Storage caves 111 Elevated structures 112 Substructures 112 Furnishings and tools 112 Handiwork 113 Pottery 113 The oUa 114 The small bowl 115 Firing 115 Weaving 115 Woodwork 116 Rope work 117 Petroglyphs 117 Transportation 118 Dress and ornament 119 Games 120 Social institutions 120 Marriage 120 The selyeme 121 Birth 122 Warihio names 123 Burial 124 63 64 CONTENTS PAGE Ceremony 125 Tuwuri 128 Pascola 131 The concluding ceremony 132 Myths 133 Creation myth 133 Myth of San Jose 134 The cross myth 134 Tales of his fathers 135 Fighting days 135 History of Tu\\njri 135 Songs of Juan Campa 136 Song of Emiliano Bourbon 136 Metamorphosis in animals 136 The Carbunco 136 Story of Juan Antonio Chapapoa 136 Social customs, ceremonial groups, and extraneous influences 137 Summary and conclusions 141 References cited 143 ILLUSTEATIONS PLATES (All plates follow p. 144) 28. a, Juan Campa and Warihio boy. -

422 Part 180—Tolerances and Ex- Emptions for Pesticide

Pt. 180 40 CFR Ch. I (7–1–16 Edition) at any time before the filing of the ini- 180.124 Methyl bromide; tolerances for resi- tial decision. dues. 180.127 Piperonyl butoxide; tolerances for [55 FR 50293, Dec. 5, 1990, as amended at 70 residues. FR 33360, June 8, 2005] 180.128 Pyrethrins; tolerances for residues. 180.129 o-Phenylphenol and its sodium salt; PART 180—TOLERANCES AND EX- tolerances for residues. 180.130 Hydrogen Cyanide; tolerances for EMPTIONS FOR PESTICIDE CHEM- residues. ICAL RESIDUES IN FOOD 180.132 Thiram; tolerances for residues. 180.142 2,4-D; tolerances for residues. Subpart A—Definitions and Interpretative 180.145 Fluorine compounds; tolerances for Regulations residues. 180.151 Ethylene oxide; tolerances for resi- Sec. dues. 180.1 Definitions and interpretations. 180.153 Diazinon; tolerances for residues. 180.3 Tolerances for related pesticide chemi- 180.154 Azinphos-methyl; tolerances for resi- cals. dues. 180.4 Exceptions. 180.155 1-Naphthaleneacetic acid; tolerances 180.5 Zero tolerances. for residues. 180.6 Pesticide tolerances regarding milk, 180.163 Dicofol; tolerances for residues. eggs, meat, and/or poultry; statement of 180.169 Carbaryl; tolerances for residues. policy. 180.172 Dodine; tolerances for residues. 180.175 Maleic hydrazide; tolerances for resi- Subpart B—Procedural Regulations dues. 180.176 Mancozeb; tolerances for residues. 180.7 Petitions proposing tolerances or ex- 180.178 Ethoxyquin; tolerances for residues. emptions for pesticide residues in or on 180.181 Chlorpropham; tolerances for resi- raw agricultural commodities or proc- dues. essed foods. 180.182 Endosulfan; tolerances for residues. 180.8 Withdrawal of petitions without preju- 180.183 Disulfoton; tolerances for residues. -

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Phan American Indians in Texas Conflict and Survival

American Indians in Texas: Conflict and Survival Texas: American Indians in AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Phan Sandy Phan AMERICAN INDIANS IN TEXAS Conflict and Survival Sandy Phan Consultant Devia Cearlock K–12 Social Studies Specialist Amarillo Independent School District Table of Contents Publishing Credits Dona Herweck Rice, Editor-in-Chief Lee Aucoin, Creative Director American Indians in Texas ........................................... 4–5 Marcus McArthur, Ph.D., Associate Education Editor Neri Garcia, Senior Designer Stephanie Reid, Photo Editor The First People in Texas ............................................6–11 Rachelle Cracchiolo, M.S.Ed., Publisher Contact with Europeans ...........................................12–15 Image Credits Westward Expansion ................................................16–19 Cover LOC[LC–USZ62–98166] & The Granger Collection; p.1 Library of Congress; pp.2–3, 4, 5 Northwind Picture Archives; p.6 Getty Images; p.7 (top) Thinkstock; p.7 (bottom) Alamy; p.8 Photo Removal and Resistance ...........................................20–23 Researchers Inc.; p.9 (top) National Geographic Stock; p.9 (bottom) The Granger Collection; p.11 (top left) Bob Daemmrich/PhotoEdit Inc.; p.11 (top right) Calhoun County Museum; pp.12–13 The Granger Breaking Up Tribal Land ..........................................24–25 Collection; p.13 (sidebar) Library of Congress; p.14 akg-images/Newscom; p.15 Getty Images; p.16 Bridgeman Art Library; p.17 Library of Congress, (sidebar) Associated Press; p.18 Bridgeman Art Library; American Indians in Texas Today .............................26–29 p.19 The Granger Collection; p.19 (sidebar) Bridgeman Art Library; p.20 Library of Congress; p.21 Getty Images; p.22 Northwind Picture Archives; p.23 LOC [LC-USZ62–98166]; p.23 (sidebar) Nativestock Pictures; Glossary........................................................................ -

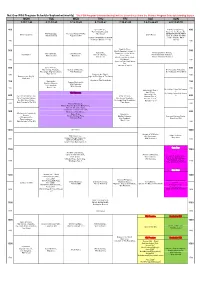

Nat Geo Wild Program Schedule September(Weekly)

Nat Geo Wild Program Schedule September(weekly) *The FOX Program Schedule(weekly) will be discontinued from the October Program Schedule(starting Septem MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 3.10.17.24 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 400 Game Of Lions、 And Man Created Dog、 400 Man Among Cheetahs、 Cesar To The Rescue III、 Wild Mississippi、 America's National Parks、 Tiger Queen SEARCH FOR THE FIRST World's Deadliest Shark Men 2 Wild Scotland II Expedition Wild DOG: A QUEST TO FIND [20th]NO TRANSMISSION DUE OUR ORIGINAL BEST TO MAINTENANCE(~7:00) FRIEND 430 430 Dead Or Alive、 500 World's Deadliest Animals 3、 500 Superpride、 World's Deadliest Animals、 Wild Cambodia、 Safari Brothers、 Symphony For Our World、 Shark Men 2 Big Cat Odyssey、 World's Deadliest Animals 2、 Wild Colombia Mygrations Shark Eden、 Man V. Lion Life On The Barrier Reef、 World's Deadliest Animals 3 530 Wild Hawaii、 530 Secrets of the Giant Manta Ray、 Moment of Impact 600 Game Of Lions、 600 Man Among Cheetahs、 Secrets of Wild India、 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER、 The Jungle King Compilation、 Wild Mississippi Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER 2 Tiger Queen 630 Snakes in the City II、 630 Snakes in the City II、 Light At The Edge of The World Earth Live 2、 Superpride、 Kingdom of The Blue Whale 700 Amazon Underworld、 700 Big Cat Odyssey、 Wild Cambodia、 Lion Gangland、 Wild Colombia Man V. Lion 730 730 Dr. -

Ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León, México

Estrada-Castillón et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2014, 10:62 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/10/1/62 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León, México Eduardo Estrada-Castillón1*, Miriam Garza-López1, José Ángel Villarreal-Quintanilla2, María Magdalena Salinas-Rodríguez1, Brianda Elizabeth Soto-Mata1, Humberto González-Rodríguez1, Dino Ulises González-Uribe2, Israel Cantú-Silva1, Artemio Carrillo-Parra1 and César Cantú-Ayala1 Abstract Background: Trough collections of plants and interviews with 110 individuals, an ethnobotanical study was conducted in order to determine the knowledge and use plant species in Rayones, Nuevo Leon, Mexico. The aim of this study was to record all useful plants and their uses, to know whether differences exist in the knowledge about the number of species and uses between women and men, and to know if there is a correlation between the age of individuals and knowledge of species and their uses. Methods: A total of 110 persons were interviewed (56 men, 56 women). Semistructured interviews were carried out. The data were analyzed by means of Student t test and the Pearson Correlation Coeficient. Results: A total of 252 species, 228 genera and 91 families of vascular plants were recorded. Astraceae, Fabaceae and are the most important families with useful species and Agave and Opuntia are the genera with the highest number of useful species. One hundred and thirty six species are considered as medicinal. Agave, Acacia and Citrus are the genera with the highest number of medicinal species. Other uses includes edible, spiritual rituals, construction and ornamentals. There was a non-significant correlation between the person’s age and number of species, but a significant very low negative correlation between the person’s age and number of uses was found. -

The Texas Band of Kickapoo Indians: an Opportunity for Progressive Congressional Action

National Indian Law Library NILL No. 010017/1981 THE INDIAN LAW SUPPORT CENTER: Federal Budget Cuts Threaten Ten-Year NARF Program Since 1972 the Native American Rights Fund has entirely, However, the protest that arose against this soon operated the Indian Law Support Center which provides forced Congress to consider legislation to continue the backup legal assistance to legal services programs serving program, although there will still be drastic cuts in the LSC's Indians on reservations, in rural communities and in urban budget for 1982. areas throughout the country. During these ten years, literally hundreds of requests for assistance in all areas of Indian law and general law have been answered annually. LSC Funding For 1982 The Support Center program has enabled NARF to reach When Congress adjourned in August, not to reconvene out and help more Indians and Native Alaskans than any until after Labor Day, there were various appropriation bills other program could possibly do. for LSC pending in the House and Senate, During 1981 the Unfortunately, this program will almost certainly come to Legal Services Corporation was funded for $321 million for .. end at the close of this year, for the Support Center is its entire national program.. The proposed House I bill, funded by the Legal Services Corporation (LSC) , which is however, cut this back to $240 million for 1982, while the itself fighting to survive the new Administration's budget Senate !Version provided for only $100 million" Where they cuts Initially, the Administration wanted to eliminate LSC will compromise on next year's appropriation for LSC is uncertain But whatever the new budget is for 1982, LSC Contents (Vol. -

Belize, March 1987

THE BLADEN BRANCH WILDERNESS Report and Recommendations of the Manomet Bird Observatory - Missouri Botanical Garden Investigation of the Upper Bladen Branch Watershed, Maya Mountains, Belize, March 1987 Nicholas V 1. Brokaw and Trevor 1. Lloyd-Evans Photographs by David C. Twichell Manomet Bird Observatory P.O, Box 936 Manomet, Massachusetts 02345 USA Many people and institutions figured importantly in our expedition to Bladen Branch and in the production of this report. We thank the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Belize, for permission to work in Bladen, especially the Honorable Dean Undo, Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. We are grateful to Chief Forest Officer Henry Flowers and Principal Forest Officer Oscar Rosada, of the Belize Forestry Department, for their assistance. Mrs. Dora Weyer inspired this investigation, and her aid with preparations in Belize was critical. We greatly appreciated Mr. Tony Zabaneh's assistance with obtaning porters and guides. The expert woodsmen Andres Logan and Arturo Rubio taught and helped us much during our exploration of Bladen. Fred and Mary Jo Prost made our stay pleasant and our business ef- ficient in Belize City. The W. W. Brehm Fund, of the Vogelpark Walsrode, West Germany funded the bulk of this project. The Brehm Fund paid for the time, transportation, special equipment, sup- plies, and services needed by expedition members from the Manomet Bird Observatory to investigate Bladen and prepare this report. Mr. Charles Luthin, Conservation Director of the Brehm Fund, helped conceive and guide the project. The Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, USA, supported plant collecting by Dr. Gerrit Davidseand Alan Brandt in Bladen. -

1. Introduction

AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics Raphael Manlay AgroParisTech GEEFT, Montpellier, France UMR Eco&Sol, Montpellier, France 14.12.2015 2 1. Introduction . Some terminology 3 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. Manlay AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Bioclimatic approach Holdridge (1967, cited by House and Hall, 2001): extension area of tropical and subtropical dry forests and woodlands = No freezing Mean annual temperature > 17°C Mean annual rainfall (MAR): 250-2000 mm PET/MAR > 1 PET: potential evapotranspiration 4 Physiognomic approach of the Forest Resource Assessment (FAO, 2010) A forest area> 0.5 ha recovery of the canopy> 10% Height of mature population> 5m Other woodland = cover of the stratum by trees able to reach 5 m high: 5-10% or by all trees: > 10% 5 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. Manlay AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Physiognomic approach A savanna (Frost et al. 1986, in House and Hall, 2001) tropical ecosystem with a more or less continuous grass cover a variable and discontinuous shrub or tree cover A tropical dry forest (Mooney et al., 1995, in Milne et al. 2006) Strong rainfall seasonality Several month-long annual drought 6 Physiognomic approach: a typology for Africa (Mayaux et al., 2004) Structural category Grass cover Shrub Tree Canopy (%) cover cover height (%) (%) (m) Grasslands sparse 1-5 none none open 5-15 none none open with sparse shrubs 15-40 <20 none closed > 40 <20 none Deciduous woodlands and shrublands shrublands > 15 1-5 shrublands with sparse trees > 15 5-15 1-5 open woodlands 15-40 > 40 1-5 Closed deciduous woodland 15-40 > 40 > 5 7 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. -

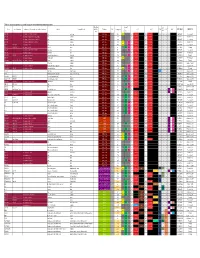

Table S1 V4.Xlsx

Table S1. Strains and genomes used in this study and relevant information pertaining to them. Clime Zone 2 Regions BIO1 Strain Other designations Original species designation (correspondent type strain) Substrate Geographic location (wild /feral Phylogeny Clade Heterozygosity1 AQY13 AQY23 RTM14 STA16 MEL7 GENOME DATA REFERENCE BIO65 pop.) ABC CBS 1175 Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. orsati Wine Switzerland WINE - Main 1 3522 15/15 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 1194 Saccharomyces ellipsoideus var. thermophilus Wine Unknown WINE - Main 1 1597 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 1479 Saccharomyces ellipsoideus var. montibensis Wine Unknown WINE - Main 1 1083 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 1192 Saccharomyces ellipsoideus var. alpinus Wine Unknown WINE - Main 1 1183 15/15 18/19 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 423 PYCC 2607 Saccharomyces chodati Wine Switzerland WINE - Main 1 4813 15/15 18/19 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 436 PYCC 8195 Saccharomyces yedo Sake moto Japan WINE - Main 1 n.d. 5/5 18/19 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x PRJEB36095 This study CBS 457 Saccharomyces ellipsoideus var. umbra Grape must Italy WINE - Main 1 5501 18/19 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. 2018 CBS 459 Saccharomyces italicus Grape must Italy WINE - Main 1 1095 NF A881del NF 11bp del x x x x ERP014555 Peter et al. -

Tersteege 1..10

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Estimating the global conservation status of more than 15,000 Amazonian tree species AUTHORS ter Steege, H; Pitman, Nigel C.A.; Killeen, TJ; et al. JOURNAL Science Advances DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 January 2016 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/19212 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication RESEARCH ARTICLE ECOLOGY 2015 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed Estimating the global conservation status of under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). more than 15,000 Amazonian tree species 10.1126/sciadv.1500936 Hans ter Steege,1,2* Nigel C. A. Pitman,3,4 Timothy J. Killeen,5 William F. Laurance,6 Carlos A. Peres,7 Juan Ernesto Guevara,8,9 Rafael P. Salomão,10 Carolina V. Castilho,11 Iêda Leão Amaral,12 FranciscaDioníziadeAlmeidaMatos,12 Luiz de Souza Coelho,12 William E. Magnusson,13 Oliver L. Phillips,14 Diogenes de Andrade Lima Filho,12 Marcelo de Jesus Veiga Carim,15 Mariana Victória Irume,12 Maria Pires Martins,12 Jean-François Molino,16 Daniel Sabatier,16 Florian Wittmann,17 Dairon Cárdenas López,18 José Renan da Silva Guimarães,15 Abel Monteagudo Mendoza,19 Percy Núñez Vargas,20 Angelo Gilberto Manzatto,21 Neidiane Farias Costa Reis,22 John Terborgh,4 Katia Regina Casula,22 Juan Carlos Montero,12,23 Ted R.