Light and the Phenology of Tropical Trees S. Joseph Wright; Carel P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographicsurvey

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 186 Anthropological Papers, No. 65 THE WARIHIO INDIANS OF SONORA-CHIHUAHUA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY By Howard Scott Gentry 61 623-738—63- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 65 Introduction 69 Informants and acknowledgments 69 Nominal note 71 Peoples of the Rio Mayo and Warihio distribution 73 Habitat 78 Arroyos 78 Canyon features 79 Hills 79 Cliffs 80 Sierra features - 80 Plants utilized 82 Cultivated plants 82 Wild plants 89 Root and herbage foods 89 Seed foods 92 Fruits 94 Construction and fuel 96 Medicinal and miscellaneous uses 99 Use of animals 105 Domestic animals 105 Wild animals and methods of capture 106 Division of labor 108 Shelter 109 Granaries 110 Storage caves 111 Elevated structures 112 Substructures 112 Furnishings and tools 112 Handiwork 113 Pottery 113 The oUa 114 The small bowl 115 Firing 115 Weaving 115 Woodwork 116 Rope work 117 Petroglyphs 117 Transportation 118 Dress and ornament 119 Games 120 Social institutions 120 Marriage 120 The selyeme 121 Birth 122 Warihio names 123 Burial 124 63 64 CONTENTS PAGE Ceremony 125 Tuwuri 128 Pascola 131 The concluding ceremony 132 Myths 133 Creation myth 133 Myth of San Jose 134 The cross myth 134 Tales of his fathers 135 Fighting days 135 History of Tu\\njri 135 Songs of Juan Campa 136 Song of Emiliano Bourbon 136 Metamorphosis in animals 136 The Carbunco 136 Story of Juan Antonio Chapapoa 136 Social customs, ceremonial groups, and extraneous influences 137 Summary and conclusions 141 References cited 143 ILLUSTEATIONS PLATES (All plates follow p. 144) 28. a, Juan Campa and Warihio boy. -

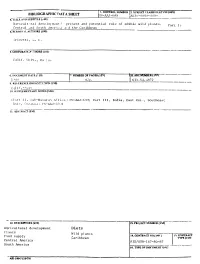

CONTROL NUMBER 27. W ' Cu-.1.SSJT:ON(€S)

m ,. CONTROL NUMBER 27.SU' W' cu-.1.SSJT:ON(€S) BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET AL-3L(-UM0F00UIEC-T00J: 9 i IE AN) SUBTIT"LE (.40) - Airicult !ral development : present and potential role of edible wild plants. Part I Central .nd So,ith :Amnerica a: ( the Caribbean 4af.RSON \1. AUrI'hORS (100) 'rivetti, L. E. 5. CORPORATE At-TH1ORS (A01) Calif. Uiliv., 1)' is. 6. nOX:U1E.N7 DATE 0)0' 1. NUMBER 3F PAGES j12*1) RLACtNUMER ([Wr I icio 8 2 p. J631.54.,G872 9. REI F.RENCE OR(GA,-?A- ION (1SO) C,I i f. -- :v., 10. SIt J'PPNIENTA.RY NOTES (500) (Part II, Suh-Sanarai Africa PN-AAJ-639; Part III, India, East Asi.., Southeast Asi cearnia PAJ6)) 11. NBS'RACT (950) 12. DESCRIPTORS (920) I. PROJECT NUMBER (I) Agricultural development Diets Plants Wild plants 14. CONTRATr NO.(I. ) i.CONTRACT Food supply Caribbean TYE(140) Central America AID/OTR-147-80-87 South America 16. TYPE OF DOCI M.NT ic: AED 590-7 (10-79) IL AGRICULTURAL DEVELOP.MMT: PRESENT AND POTENI.AL ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS PART I CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN November 1980 REPORT TO THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Alb/mr-lq - 6 _ 7- AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: PRESENT AND POTENTIAL ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS PART 1 CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN by Louis Evan Grivetti Departments of Nutrition and Geography University of California Davis, California 95616 With the Research Assistance of: Christina J. Frentzel Karen E. Ginsberg Kristine L. -

1. Introduction

AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics Raphael Manlay AgroParisTech GEEFT, Montpellier, France UMR Eco&Sol, Montpellier, France 14.12.2015 2 1. Introduction . Some terminology 3 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. Manlay AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Bioclimatic approach Holdridge (1967, cited by House and Hall, 2001): extension area of tropical and subtropical dry forests and woodlands = No freezing Mean annual temperature > 17°C Mean annual rainfall (MAR): 250-2000 mm PET/MAR > 1 PET: potential evapotranspiration 4 Physiognomic approach of the Forest Resource Assessment (FAO, 2010) A forest area> 0.5 ha recovery of the canopy> 10% Height of mature population> 5m Other woodland = cover of the stratum by trees able to reach 5 m high: 5-10% or by all trees: > 10% 5 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. Manlay AgroParisTech - Formations GEEFT et BioGET 2015-2016 Physiognomic approach A savanna (Frost et al. 1986, in House and Hall, 2001) tropical ecosystem with a more or less continuous grass cover a variable and discontinuous shrub or tree cover A tropical dry forest (Mooney et al., 1995, in Milne et al. 2006) Strong rainfall seasonality Several month-long annual drought 6 Physiognomic approach: a typology for Africa (Mayaux et al., 2004) Structural category Grass cover Shrub Tree Canopy (%) cover cover height (%) (%) (m) Grasslands sparse 1-5 none none open 5-15 none none open with sparse shrubs 15-40 <20 none closed > 40 <20 none Deciduous woodlands and shrublands shrublands > 15 1-5 shrublands with sparse trees > 15 5-15 1-5 open woodlands 15-40 > 40 1-5 Closed deciduous woodland 15-40 > 40 > 5 7 Some features of tree ecosystems in the dry tropics - R. -

ÁRBOLES Listado Alfabético Por Nombre Común De Especies De La

Listado alfabético por nombre común de especies de la Paleta Vegetal ÁRBOLES Nombre común Common name Nombre científico Familia Alejo, arellano, palo colorado, Cascalote Caesalpinia platyloba Fabaceae hueilaqui Amapa, pata de león, roble Tabebuia chrysantha Golden trumpet tree Bignoniaceae serrano, cortez blanco (Handroanthus chrysanthus) Amole, pipe, jaboncillo, Soapberry Sapindus saponaria Sapindaceae chumbimbo Ayal, chookari, cirian, cuatecomate, árbol de tocomate, comate, cuate, Jícaro Crescentia alata Bignoniaceae jícara, morro del llano, guajito sírial, guiro Cacaloxochitl, cacalosuchil, plumeria, frangipani, flor de Frangipani Plumeria rubra Apocynaceae mazapán Cascalote Thorness cascalote Caesalpinia cacalaco Fabaceae Ciruelo mexicano, yoyomo Purple mombin Spondias purpurea Anacardiaceae Clavellina, coquito Shaving brush tree Pseudobombax ellipticum Malvaceae Cuajiote, torote colorado, Elephant tree Bursera microphylla Burseraceae torote blanco, copal, jarilla Acacia cochliacantha Cucharito, cubata, chírahui Cubata Fabaceae (Vachellia campeachiana) Ébano de Texas Texas ebony Ebenopsis ebano Fabaceae 1 ÁRBOLES Nombre común Common name Nombre científico Familia Ébano, palo freno, tubchi Ebony Caesalpinia sclerocarpa Fabaceae Guaje, liliaque, peladera, huachi White leadtree Leucaena leucocephala Mimosaceae Guamúchil Monkeypod Pithecellobium dulce Mimosaceae Guayacán, árbol santo, palo Pockwood Guaiacum coulteri Zygophyllaceae santo, matlaquahuit Huanacaxtle, árbol de las Ear pod tree Enterolobium cyclocarpum Fabaceae orejas, guanacaste -

Gavin Ballantyne Phd Thesis

ANTS AS FLOWER VISITORS: FLORAL ANT-REPELLENCE AND THE IMPACT OF ANT SCENT-MARKS ON POLLINATOR BEHAVIOUR Gavin Ballantyne A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2535 This item is protected by original copyright Ants as flower visitors: floral ant-repellence and the impact of ant scent-marks on pollinator behaviour Gavin Ballantyne University of St Andrews 2011 Supervisor: Prof Pat Willmer - This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents, the half that are here and the half that have gone, and to taking photos of random things. - “Look in the mirror, and don't be tempted to equate transient domination with either intrinsic superiority or prospects for extended survival.” - Stephen Jay Gould “I am comforted and consoled in finding it immeasurably remote in time, gloriously lacking in any relevance for our day.” - Umberto Eco i Declarations Candidate's declarations I, Gavin Ballantyne, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 59,600 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in June, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in Biology; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2011. -

How Will Bark Contribute to Plant Survival Under Climate Change? a Comparison of Plant Communities in Wet and Dry Environments

How will bark contribute to plant survival under climate change? A comparison of plant communities in wet and dry environments. Julieta Rosell, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [email protected] INTRODUCTION Climate change and the effect on vegetation structure and function Climate change is bringing new conditions of temperature, rainfall, and fire regime in most of the world (Ipcc, 2014). These new conditions are affecting ecosystems worldwide, including forests. Forests in general, and tropical forests in particular, have a very strong role in the regulation of climate (Bonan, 2008) and are crucial to the provision of multiple ecosystem services (Brandon, 2014). Because of this importance, there is an ever- increasing interest in understanding how tropical forests respond to these new climate conditions (Cavaleri et al., 2015). Understanding the mechanistic causes of these responses is crucial to manage the effect of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems. Several studies have addressed the effect of new climate conditions on plant traits and performance (Corlett & Westcott, 2013; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2013; Law, 2014; Tausz & Grulke, 2014). These studies have indicated that, for example, plants have started to produce flowers and leaves earlier in spring (Cleland et al., 2012), and that higher net primary productivity will increase as a result of climate change in certain areas (Nemani et al., 2003), whereas increased tree mortality will be expected in others (Anderegg et al., 2013). Most studies have mainly focused on well known organs such as leaves (Li et al., 2015) and wood (Choat et al., 2012). Despite being so important for plant function and representing a significant amount of biomass, the role of bark in the response to climate change and in plant survival in general is unclear. -

Regeneration Dynamics in Response to Slash-And-Burn Agriculture in a Tropical

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Daniela Roth for the degree of Master of Science in Rangeland Resources presented on January 5, 1996. Title: Regeneration Dynamics in Response to Slash-and-Burn Agriculture in a Tropical Deciduous Forest in Western Mexico. Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Patricia M. Miller Few studies have focused on the response of woody vegetation and seed banks to slash-and-burn agriculture in tropical deciduous forest ecosystems. To bridge this gap in knowledge, the following research project was undertaken. Pasture conversion fires killed 87% of the sampled woody plants that had sprouted following slashing of a tropical deciduous forest. Species richness was reduced by 40%. Prior to burning 96% of all sampled plants sprouted from above-ground tissues. Post-burn 98% of the survivors sprouted from below-ground tissues. During the first year following pasture conversion, survival of sprouting plants was high, 91%. Average height, elliptical crown area, and total area covered by sprouting plants tripled, average crown volume increased over 500% within a year. To document impacts on species composition, density, and structure prior to and following pasture conversion, transects were established in the intact forest in 1992 and following pasture conversion in 1994. Additional transects were established in an adjacent 10-year old pasture. The intact forest had an average density of 3115 ± 137 (3T± 1 SE) woody plants/ha (DBH z 2.5 cm), containing 59 species. Following pasture conversion the average density of woody plants/ha (stump diameter 1.0 cm) was 1338 ± 133. Thirty-six species were identified. The ten year old pasture had an average density of 1592 ± 105 woody plants/ha, containing 32 species. -

1 Seasonal Changes in Light Availability Determine the Inverse Leafing Phenology of Jacquinia Nervosa (Theophrastaceae), a Neotr

Seasonal changes in light availability determine the inverse leafing phenology of Jacquinia nervosa (Theophrastaceae), a neotropical dry forest understory shrub Óscar M. Chaves1 and Gerardo Avalos2 1Escuela de Biología Universidad de Costa Rica 2060 San Pedro San José Costa Rica FAX: (506) 207-4216 2 The School for Field Studies Center for Sustainable Development Studies 16 Broadway Beverly MA 01915-4435 USA ABSTRACT. The leafing phenology of tropical plants has been primarily associated with seasonal changes in the availability of water and light. In Tropical Dry Forests most plants are deciduous during the dry season and flush new leaves at the onset of the rains. In contrast to this pattern, a small group of species present an inverse strategy of leaf production, being deciduous during the wet season and flushing new leaves during the dry season. In Costa Rica, the only species with such behavior is the phreatophytic understory shrub Jacquinia nervosa (Theoprastaceae). In this study, we determined how seasonal changes in light availability (photon flux density, PFD) influence the leafing and reproductive phenology of this species. We monitored leaf production, leaf survival and leaf life span in 36 adult plants (1.2-5.5 m in height) during 16 months (April 2000 through October 2001) in Santa Rosa National Park. Leaf censuses, as well as flower and fruit counts (when available), were done every two weeks. Changes in PFD were monitored using canopy photos to measure the direct and indirect radiation reaching each plant from December 2000 to February 2001. We also analyzed how leaf structure matched dry season conditions by inspecting changes in leaf specific mass, leaf expansion rates, and internal leaf anatomy. -

TESIS: Fenología Invertida En Jacquinia Nervosa: Un Mecanismo De Escape De La Herbivoría En Una Selva Estacional

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO POSGRADO EN CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS INSTITUTO DE ECOLOGÍA Fenología invertida en Jacquinia nervosa: Un mecanismo de escape de la herbivoría en una selva estacional T E S I S QUE PARA OBTENER EL GRADO ACADÉMICO DE MAESTRO EN CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS (BIOLOGÍA AMBIENTAL) P R E S E N T A LUIS OCTAVIO SÁNCHEZ LIEJA DIRECTOR DE TESIS: DR. RODOLFO DIRZO MÉXICO, D. F. MAYO, 2006 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. COORDINACIÓN lng. Le::ipoldo Sil\la GIJliérrez )i,e-::t:,r General de Admini$tl'i:lci~n Escoa,, ur-.:..•.t =rcs~n1é Por r.•edilJ de la ¡:;resenll:; ni:i J;:t!nnito :"lfcrmar a ust.¡,;! o.~~·· :z- -eu:-,ón ordinaria del Com,:e A~r.1ioo ,:le Posgradc 1.11 Ciffl1cia$ 6iol0gicas. oo~hra:111 el d:a 21 de ,v.,v1l!mbre del 2·J:>S, ss ~unJc·> pone• a sJ 1:011sQeración el S;QJieinta .iur..1:J::i para el exar:i,n de 9111do de tAacst,ia &'! C erx;i~s BiclCg1cos (Bic.l~ia .~n•bienta) cel alurroo Sanchez Lieja Luis Octavio con nllroo10 de cu11ntc 504008821 :on 'a to.3is htul~a; "Fonofogí.1 Invertida en Jacqulnla nervO\a: Un nioeanlsmo de esc3pe de la he,bivorí.e e11 una selva ..st.acional", b:Ajo ,a dif'9oc1l:n .ja.,I Dr. -

Phylogenetic Distribution and Evolution of Mycorrhizas in Land Plants

Mycorrhiza (2006) 16: 299–363 DOI 10.1007/s00572-005-0033-6 REVIEW B. Wang . Y.-L. Qiu Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of mycorrhizas in land plants Received: 22 June 2005 / Accepted: 15 December 2005 / Published online: 6 May 2006 # Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract A survey of 659 papers mostly published since plants (Pirozynski and Malloch 1975; Malloch et al. 1980; 1987 was conducted to compile a checklist of mycorrhizal Harley and Harley 1987; Trappe 1987; Selosse and Le Tacon occurrence among 3,617 species (263 families) of land 1998;Readetal.2000; Brundrett 2002). Since Nägeli first plants. A plant phylogeny was then used to map the my- described them in 1842 (see Koide and Mosse 2004), only a corrhizal information to examine evolutionary patterns. Sev- few major surveys have been conducted on their phyloge- eral findings from this survey enhance our understanding of netic distribution in various groups of land plants either by the roles of mycorrhizas in the origin and subsequent diver- retrieving information from literature or through direct ob- sification of land plants. First, 80 and 92% of surveyed land servation (Trappe 1987; Harley and Harley 1987;Newman plant species and families are mycorrhizal. Second, arbus- and Reddell 1987). Trappe (1987) gathered information on cular mycorrhiza (AM) is the predominant and ancestral type the presence and absence of mycorrhizas in 6,507 species of of mycorrhiza in land plants. Its occurrence in a vast majority angiosperms investigated in previous studies and mapped the of land plants and early-diverging lineages of liverworts phylogenetic distribution of mycorrhizas using the classifi- suggests that the origin of AM probably coincided with the cation system by Cronquist (1981). -

Is the Inverse Leafing Phenology of the Dry Forest Understory Shrub Jacquinia Nervosa (Theophrastaceae) a Strategy to Escape Herbivory?

Is the inverse leafing phenology of the dry forest understory shrub Jacquinia nervosa (Theophrastaceae) a strategy to escape herbivory? Óscar M. Chaves1 & Gerardo Avalos1,2 1 Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] 2 The School for Field Studies, Center for Sustainable Development Studies, 10 Federal St., Salem, MA 01970 USA; [email protected] Received 03-VIII-2005. Corrected 25-I-2006. Accepted 23-V-2006. Abstract: In the dry forest of Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica, the understory shrub Jacquinia nervosa presents an inverse pattern of phenology that concentrates vegetative growth and reproduction during the dry season. In this study, we tested the “escape from herbivory” hypothesis as a potential explanation for the inverse phenological pattern of J. nervosa. We monitored leaf, flower and fruit production in 36 adult plants from October 2000 to August 2001. Leaves of six randomly selected branches per plant were marked and monitored every two weeks to measure the cumulative loss in leaf area. To analyze pre-dispersal seed predation we col- lected 15 fruits per plant and counted the total number of healthy and damaged seeds, as well as the number and type of seed predators found within the fruits. Leaf, flower, and fruit production occurred during the first part of the dry season (end of November to February). The cumulative herbivory levels were similar to those observed in other tropical dry forest tree species that concentrate leaf production during the wet season, and were concen- trated on young leaves, which lost an average of 36.77 % of their area (SD= 34.35 %, N= 195). -

Cultural Change and Loss of Ethnoecological Knowledge Among

Saynes-Vásquez et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2013, 9:40 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/9/1/40 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Cultural change and loss of ethnoecological knowledge among the Isthmus Zapotecs of Mexico Alfredo Saynes-Vásquez1, Javier Caballero1*, Jorge A Meave2 and Fernando Chiang3 Abstract Background: Global changes that affect local societies may cause the loss of ecological knowledge. The process of cultural change in Zapotec communities of the Oaxacan Isthmus intensified during the first years of the 20th century due to industrial and agro-industrial modernization projects and an increase in the level of formal schooling. Based on the case of the Oaxacan Isthmus, this study assesses the relationship between cultural change and the loss of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). Methods: Three hundred male heads of family were interviewed from three municipalities in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, Mexico selected to span a wide range of cultural change. Each participant was shown herbarium specimens and photographs of a sample of 30 species drawn from a pool of 94 representing local plant diversity. Visual recognition of each species, knowledge of plant form, generic name, specific name, and local uses were scored. The sum of the five scores provided an index of global knowledge which we used as a proxy for TEK. Analysis of variance revealed differences between groups of economic activities. We collected socio-demographic data from the interviewees such as age, level of schooling, and competency in the local language. With these data we ran a principal component analysis and took the first axis as an index of cultural change, and correlated it with the scores obtained each respondent.