An Ethnographicsurvey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reorganization of the Huichol Ceremonial Precinct (Tukipa) of Guadalupe Ocotán, Nayarit, México Translation of the Spanish by Eduardo Williams

FAMSI © 2007: Víctor Manuel Téllez Lozano The Reorganization of the Huichol Ceremonial Precinct (Tukipa) of Guadalupe Ocotán, Nayarit, México Translation of the Spanish by Eduardo Williams Research Year : 2005 Culture : Huichol Chronology : Modern Location : Nayarit, México Site : Guadalupe Ocotán Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Linguistic Note Introduction Architectural Influences The Tukipa District of Xatsitsarie The Revolutionary Period and the Reorganization of the Community The Fragmentation of the Community The Tukipa Precinct of Xatsitsarie Conclusions Acknowledgements Appendix: Ceremonial precincts derived from Xatsitsarie’s Tuki List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract This report summarizes the results of research undertaken in Guadalupe Ocotán, a dependency and agrarian community located in the municipality of La Yesca, Nayarit. This study explores in greater depth the political and ceremonial relations that existed between the ceremonial district of Xatsitsarie and San Andrés Cohamiata , one of three Wixaritari (Huichol) communities in the area of the Chapalagana River, in the northern area of the state of Jalisco ( Figure 1 , shown below). Moreover, it analyzes how the destruction of the Temple ( Tuki ) of Guadalupe Ocotán, together with the modification of the community's territory, determined the collapse of these ceremonial links in the second half of the 20th century. The ceremonial reorganization of this district is analyzed using a diachronic perspective, in which the ethnographic record, which begins with Lumholtz' work in the late 19th century, is contrasted with reports by missionaries and oral history. Similarly, on the basis of ethnographic data and information provided by archaeological studies, this study offers a reinterpretation of certain ethnohistorical sources related to the antecedents of these ceremonial centers. -

Frecker's Saddlery

Frecker’s Saddlery Frecker’s 13654 N 115 E Idaho Falls, Idaho 83401 addlery (208) 538-7393 S [email protected] Kent and Dave’s Price List SADDLES FULL TOOLED Base Price 3850.00 5X 2100.00 Padded Seat 350.00 7X 3800.00 Swelled Forks 100.00 9X 5000.00 Crupper Ring 30.00 Dyed Background add 40% to tooling cost Breeching Rings 20.00 Rawhide Braided Hobble Ring 60.00 PARTIAL TOOLED Leather Braided Hobble Ring 50.00 3 Panel 600.00 5 Panel 950.00 7 Panel 1600.00 STIRRUPS Galvanized Plain 75.00 PARTIAL TOOLED/BASKET Heavy Monel Plain 175.00 3 Panel 500.00 Heavy Brass Plain 185.00 5 Panel 700.00 Leather Lined add 55.00 7 Panel 800.00 Heel Blocks add 15.00 Plain Half Cap add 75.00 FULL BASKET STAMP Stamped Half Cap add 95.00 #7 Stamp 1850.00 Tooled Half Cap add 165.00 #12 Stamp 1200.00 Bulldog Tapadero Plain 290.00 Bulldog Tapadero Stamped 350.00 PARTIAL BASKET STAMP Bulldog Tapadero Tooled 550.00 3 Panel #7 550.00 Parade Tapadero Plain 450.00 5 Panel #7 700.00 Parade Tapadero Stamped (outside) 500.00 7 Panel #7 950.00 Parade Tapadero Tooled (outside) 950.00 3 Panel #12 300.00 Eagle Beak Tapaderos Tooled (outside) 1300.00 5 Panel #12 350.00 7 Panel #12 550.00 BREAST COLLARS FULL BASKET/TOOLED Brannaman Martingale Plain 125.00 #7 Basket/Floral Pattern 2300.00 Brannaman Martingale Stamped 155.00 #12 Basket/Floral 1500.00 Brannaman Martingale Basket/Tooled 195.00 Brannaman Martingale Tooled 325.00 BORDER STAMPS 3 Piece Martingale Plain 135.00 Bead 150.00 3 Piece Martingale Stamped 160.00 ½” Wide 250.00 3 Piece Martingale Basket/Tooled 265.00 -

Public Auction

PUBLIC AUCTION Mary Sellon Estate • Location & Auction Site: 9424 Leversee Road • Janesville, Iowa 50647 Sale on July 10th, 2021 • Starts at 9:00 AM Preview All Day on July 9th, 2021 or by appointment. SELLING WITH 2 AUCTION RINGS ALL DAY , SO BRING A FRIEND! LUNCH STAND ON GROUNDS! Mary was an avid collector and antique dealer her entire adult life. She always said she collected the There are collections of toys, banks, bookends, inkwells, doorstops, many items of furniture that were odd and unusual. We started with old horse equipment when nobody else wanted it and branched out used to display other items as well as actual old wood and glass display cases both large and small. into many other things, saddles, bits, spurs, stirrups, rosettes and just about anything that ever touched This will be one of the largest offerings of US Army horse equipment this year. Look the list over and a horse. Just about every collector of antiques will hopefully find something of interest at this sale. inspect the actual offering July 9th, and July 10th before the sale. Hope to see you there! SADDLES HORSE BITS STIRRUPS (S.P.) SPURS 1. U.S. Army Pack Saddle with both 39. Australian saddle 97. U.S. civil War- severe 117. US Calvary bits All Model 136. Professor Beery double 1 P.R. - Smaller iron 19th 1 P.R. - Side saddle S.P. 1 P.R. - Scott’s safety 1 P.R. - Unusual iron spurs 1 P.R. - Brass spurs canvas panniers good condition 40. U.S. 1904- Very good condition bit- No.3- No Lip Bar No 1909 - all stamped US size rein curb bit - iron century S.P. -

Wrote in Cucurpe, on 30Th April 1689, to His Aunt Francisca Adlmann in Škofja Loka, Slovenia

UDK 929 Kappus M. A. A LETTER OF MARCUS ANTONIUS KAPPUS TO EUSEBIUS FRANCISCUS KINO (SONORA IN1690) Tomaž Nabergoj INTRODUCTION The life and work of the Slovene Jesuit, Marcus Antonius Kappus (1657 -1717) who, three centuries ago, worked as a missionary in Sonora, north-west Mexico, has, in recent years, been the subject of several short studies in Slovenia. In this journal, Professor Janez Stanonik has, so far, published five letters which Kappus sent home to his relatives and friends, and one letter which he sent to hi s friend in Vienna, 1 as well as a study on the collection of poems (276 chronograms) in Latin, which Kappus published in Mexico City, in 1708, entitled IHS. Enthusiasmus sive solemnes !udi poe tici. 2 Prompted by the above publications, the author of this paper spent a month in Sonora while journeying in Mexico in 1991. In Archivo General de la Naci6n (the general Mexican archives) in Mexico City, he happened to find another letter written by Marcus Antonius Kappus. The letter comprises two A4 pages and is kept in Archivo Hist6rico de la Hacienda, legajo 279, expediente 19.3 This, hitherto unpublished document, was written by Kappus on 25th November 1690, in Cucurpe, and is addressed to Eusebius Franciscus Kino, his superior. Chronologically, it is one of his earliest preserved letters. Among those so far published, as far as we know, it is the only one preserved in original. At the same time this is Kappus' second earliest preserved letter written in Sonora. The first he wrote in Cucurpe, on 30th April 1689, to his aunt Francisca Adlmann in Škofja Loka, Slovenia. -

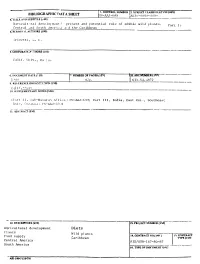

CONTROL NUMBER 27. W ' Cu-.1.SSJT:ON(€S)

m ,. CONTROL NUMBER 27.SU' W' cu-.1.SSJT:ON(€S) BIBLIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET AL-3L(-UM0F00UIEC-T00J: 9 i IE AN) SUBTIT"LE (.40) - Airicult !ral development : present and potential role of edible wild plants. Part I Central .nd So,ith :Amnerica a: ( the Caribbean 4af.RSON \1. AUrI'hORS (100) 'rivetti, L. E. 5. CORPORATE At-TH1ORS (A01) Calif. Uiliv., 1)' is. 6. nOX:U1E.N7 DATE 0)0' 1. NUMBER 3F PAGES j12*1) RLACtNUMER ([Wr I icio 8 2 p. J631.54.,G872 9. REI F.RENCE OR(GA,-?A- ION (1SO) C,I i f. -- :v., 10. SIt J'PPNIENTA.RY NOTES (500) (Part II, Suh-Sanarai Africa PN-AAJ-639; Part III, India, East Asi.., Southeast Asi cearnia PAJ6)) 11. NBS'RACT (950) 12. DESCRIPTORS (920) I. PROJECT NUMBER (I) Agricultural development Diets Plants Wild plants 14. CONTRATr NO.(I. ) i.CONTRACT Food supply Caribbean TYE(140) Central America AID/OTR-147-80-87 South America 16. TYPE OF DOCI M.NT ic: AED 590-7 (10-79) IL AGRICULTURAL DEVELOP.MMT: PRESENT AND POTENI.AL ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS PART I CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN November 1980 REPORT TO THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT Alb/mr-lq - 6 _ 7- AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT: PRESENT AND POTENTIAL ROLE OF EDIBLE WILD PLANTS PART 1 CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN by Louis Evan Grivetti Departments of Nutrition and Geography University of California Davis, California 95616 With the Research Assistance of: Christina J. Frentzel Karen E. Ginsberg Kristine L. -

Edible Leafy Plants from Mexico As Sources of Antioxidant Compounds, and Their Nutritional, Nutraceutical and Antimicrobial Potential: a Review

antioxidants Review Edible Leafy Plants from Mexico as Sources of Antioxidant Compounds, and Their Nutritional, Nutraceutical and Antimicrobial Potential: A Review Lourdes Mateos-Maces 1, José Luis Chávez-Servia 2,* , Araceli Minerva Vera-Guzmán 2 , Elia Nora Aquino-Bolaños 3 , Jimena E. Alba-Jiménez 4 and Bethsabe Belem Villagómez-González 2 1 Recursos Genéticos y Productividad-Genética, Colegio de Posgraduados, Carr. México-Texcoco Km. 36.5, Montecillo, Texcoco 56230, Mexico; [email protected] 2 CIIDIR-Oaxaca, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Ciudad de México 07738, Mexico; [email protected] (A.M.V.-G.); [email protected] (B.B.V.-G.) 3 Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo de Alimentos, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa-Enríquez 1090, Mexico; [email protected] 4 CONACyT-Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo de Alimentos, Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa-Enríquez 1090, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 May 2020; Accepted: 13 June 2020; Published: 20 June 2020 Abstract: A review of indigenous Mexican plants with edible stems and leaves and their nutritional and nutraceutical potential was conducted, complemented by the authors’ experiences. In Mexico, more than 250 species with edible stems, leaves, vines and flowers, known as “quelites,” are collected or are cultivated and consumed. The assessment of the quelite composition depends on the chemical characteristics of the compounds being evaluated; the protein quality is a direct function of the amino acid content, which is evaluated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the contribution of minerals is evaluated by atomic absorption spectrometry, inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) or ICP mass spectrometry. The total contents of phenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, saponins and other general compounds have been analyzed using UV-vis spectrophotometry and by HPLC. -

Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003)

ISSN 0486-4271 IOS Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Index nominum novarum plantarum succulentarum anno MMIII editorum nec non bibliographia taxonomica ab U. Eggli et D. C. Zappi compositus. International Organization for Succulent Plant Study Internationale Organisation für Sukkulentenforschung December 2004 ISSN 0486-4271 Conventions used in Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum — Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum attempts to list, under separate headings, newly published names of succulent plants and relevant literature on the systematics of these plants, on an annual basis. New names noted after the issue for the relevant year has gone to press are included in later issues. Specialist periodical literature is scanned in full (as available at the libraries at ZSS and Z or received by the compilers). Also included is information supplied to the compilers direct. It is urgently requested that any reprints of papers not published in readily available botanical literature be sent to the compilers. — Validly published names are given in bold face type, accompanied by an indication of the nomenclatu- ral type (name or specimen dependent on rank), followed by the herbarium acronyms of the herbaria where the holotype and possible isotypes are said to be deposited (first acronym for holotype), accord- ing to Index Herbariorum, ed. 8 and supplements as published in Taxon. Invalid, illegitimate, or incor- rect names are given in italic type face. In either case a full bibliographic reference is given. For new combinations, the basionym is also listed. For invalid, illegitimate or incorrect names, the articles of the ICBN which have been contravened are indicated in brackets (note that the numbering of some regularly cited articles has changed in the Tokyo (1994) edition of ICBN). -

Identities in Motion the Formation of a Plural Indio Society in Early San Luis Potosí, New Spain, 1591-1630

Identities in Motion The Formation of a Plural Indio Society in Early San Luis Potosí, New Spain, 1591-1630 Laurent Corbeil Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montréal September 2014 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of doctor in philosophy ©Laurent Corbeil, 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................ ii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iv Résumé ............................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Historiography, Methodology, and Concepts ................................................. 15 Perspectives on Indigenous Peoples ............................................................................. 16 Identity .......................................................................................................................... 25 Sources and Methodology............................................................................................. 29 A Short Note on Terminology ..................................................................................... -

Literature Cited

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 19, 20, and 21, whether as selected references, in text, or in nomenclatural contexts. In citations of articles, both here and in the taxonomic treatments, and also in nomenclatural citations, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbre- viated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. In nomenclatural citations (only), book titles are rendered in the abbreviated forms recommended in F. A. Stafleu and R. S. Cowan (1976–1988) and F. A. Stafleu and E. A. Mennega (1992+). Here, those abbreviated forms are indicated parenthetically following the full citations of the corresponding works, and cross references to the full citations are interpolated in the list alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix “a”; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with “b”. Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. -

Hummingbird Delight Designed by Christine Woods of Matrix Gardens

2018 garden in a box: Garden Info Sheet Hummingbird Delight Designed by Christine Woods of Matrix Gardens 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 - Angelina Stonecrop 5 - Knautia 9 - Rondo Penstemon 2 - Blue Grama Grass 6 - Pineleaf Penstemon 10 - Silver Blade Evening Primrose 3 - Chocolate Flower 7 - Red Carpet Stonecrop 11 - Sunset Hyssop 4 - Faassen’s Catmint 8 - Red Rocks Penstemon Angelina Stonecrop Blue Grama Grass 1 Latin Name: Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’ 2 Latin Name: Bouteloua gracilis Mature Height: 4-6” Mature Height: 1-2’ Mature Spread: 12-18” Mature Spread: 1-2’ Hardy To: 8,000’ Hardy To: 8,500’ Water: Low Water: Very Low Exposure: Sun Exposure: Sun Flower Color: Yellow Flower Color: Tan or Blonde Flower Season: Summer Flower Season: Summer to Fall Attracts: Hummingbirds, Bees, Butterflies Attracts: Small Birds Description: Bottom line, Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’ is gorgeous Description: Bouteloua gracilis is a greyish-green native grass and easy to care for! Its vibrant chartreuse foliage adds a distinct commonly found in the Rocky Mountains. This attractive and hardy pop of color to the landscape in the form of a low growing succu- grass will compliment and add intrigue to any established garden. lent mat. Often, the tips of the foliage will feature a dark amber Bouteloua gracilis will stay colorful all the way through the fall color, adding to its appeal. With the changing seasons, the hue of season. Its delicate blonde “eyelash-like” spikelets grow horizontally this plant will transform. Generally, it will display lime green foliage on the grass stems. -

2015 Price List Gabriel Valley Farms 440 Old Hwy

2015 Price List Gabriel Valley Farms 440 Old Hwy. 29 East Georgetown, TX 78626 (512) 930-0923 www.gabrielvalleyfarms.com January 1, 2015 Dear Valued Customer, 2014 was a very momentous year at Gabriel Valley Farms as we celebrated a quarter of a century in business. Whew! It’s been an incredible journey and we look forward to many more years of growing certified organic herb & vegetable plants plus other specialties. We are expanding our edible line this year and adding Blackberries, Ginger, Mulberry and more Fig varieties. In addition, Sam has found some assorted, authentic Thai peppers to add to his eclectic collection as well as the infamous Ghost and Trinidad Scorpion peppers. In accordance with the National Organic Standards, we must always purchase organic seed or starter plants whenever available. We many never use GMO or treated seeds. In addition, we must maintain extensive records on all of our practices (fertilizing, insect control, propagation, etc.) and we are subject to a lengthy annual report and inspection. In spite of the added work load, we feel it’s worth it to produce a healthy, quality, locally grown product for you and your customers. We thank you for choosing Gabriel Valley Farms as your supplier. We appreciate your business and we look forward to providing you with dependable, courteous service. Look for our yellow plant id tag with the USDA Certified Organic logo. Best wishes for a prosperous year! Sam & Cathy Slaughter, Daniel Young – Owners And all the staff at GVF Gabriel Valley Farms Serving The Central Texas Area Since 1989 HERB OF THE YEAR 2015: SAVORY (Satureja) Summer Savory Saturjea hortensis A fast growing, bushy, short lived annual herb. -

2019 NATIVE PLANT SALE UTEP CENTENNIAL MUSEUM CHIHUAHUAN DESERT GARDENS Available Species List

2019 NATIVE PLANT SALE UTEP CENTENNIAL MUSEUM CHIHUAHUAN DESERT GARDENS Available Species List Name Type: Water: Sun: Wildlife: Notes: H x W: Spacing: ColdHardy: Agave ovatifolia Accent L F/P Wide, powder-blue leaves and a tall, branching flower stalk with clusters of Whale's Tongue Agave 3' x 4' 4 0º F light green flowers. Agave parryi var. truncata Accent VL F/P Very xeric, thick toothed leaves in a tight whorl. Good in containers. Artichoke Agave 3' x 3' 3' 10º F Agave victoriae-reginae 'Compacta' Accent L F Small, compact, slow growing. Good in pots Compact Queen Victoria Agave 12" x 12" 12" 10º F Anisacanthus quadrifidus var. wrightii 'Mexican Shrub L/M F H Summer hummer favorite, orange Fire' flowers, xeric, deciduous. Mexican Flame, 'Mexican Fire' 4-5' x 4-5' 5' 0º F * Aquilegia chrysantha Perennial M/H PSh/ Needs moist soil, showy yellow flowers FSh spring to fall. Golden Columbine 3' x 3' 3' -30º F * Artemisia filifolia Shrub L F Silver foliage, sand loving, xeric plant. Use as a color foil. Sand Sage 3' x 3' 3-4' -10º F Artemisia frigida Shrub L F Fine silver foliage, small accent. Fringed Sage 1’ x 2’ 2' -30º F * Berlandiera lyrata Perennial L F/P B Very fragrant (chocolate) yellow flowers spring to fall. Good bedding Chocolate Flower 1' x 2' 2' -20º F plant. * Bouteloua curtipendula Grass L F Seeds Bunching Perennial/ Grass/ with large drooping seeds. Good for wildlife. Sideoats Grama 2' x 2' 2-3' -10º F * Bouteloua gracilis 'Blond Ambition' Grass L/M F Seeds Soft Perennial/ bunch Grass/ with eyelash seed heads and chartreuse Blue Grama, 'Blond Ambition' 2.5- x 2.5- 2.5-3’ -20º F flowers.