Chapel Hill Zen Center Chant Book ___Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage ew Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISB: 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San First Printing, 2002 – 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 – 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety , for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma , is allowed after prior notification to the author. ew Cover Design Inset photo shows the famous Reclining Buddha image at Kusinara. Its unique facial expression evokes the bliss of peace ( santisukha ) of the final liberation as the Buddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the Great Stupa of Sanchi located near Bhopal, an important Buddhist shrine where relics of the Chief Disciples and the Arahants of the Third Buddhist Council were discovered. Printed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by: Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd., 68, Jalan 14E, Ampang New Village, 68000 Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel: 03-42916001, 42916002, Fax: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATIO This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to India from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in Buddhism, have made those journeys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

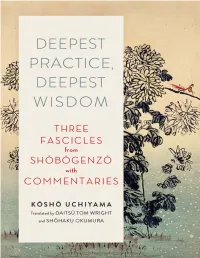

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

Pratica E Illuminazione in Dôgen

ALDO TOLLINI Pratica e illuminazione in Dôgen Traduzione di alcuni capitoli dello Shôbôgenzô PARTE PRIMA INTRODUZIONE A DÔGEN La vita e le opere di Dôgen Dôgen fu uno dei più originali pensatori e dei più importanti riformatori religiosi giapponesi. Conosciuto col nome religioso di Dôgen Kigen o Eihei Dôgen, nel 1227 fondò la scuola Sôtô Zen, una delle più importanti e diffuse scuole buddhiste giapponesi che ancora oggi conta moltissimi seguaci. Fondò il monastero di Eiheiji nella prefettura di Fukui e scrisse lo Shôbôgenzô (1231/1253, il "Tesoro dell’occhio della vera legge"), diventato un classico della tradizione buddhista giapponese. Pur vivendo nel mezzo della confusione della prima parte dell’era Kamakura (1185-1333) egli perseguì con grande determinazione e profondità l’esperienza religiosa buddhista. Nacque a Kyoto da nobile famiglia, forse figlio di Koga Michichika (1149-1202) una figura di primo piano nell'ambito della corte. Rimase orfano da bambino facendo diretta esperienza della realtà dell’impermanenza, che diventerà un concetto chiave del suo pensiero. Entrò nella vita monastica come monaco Tendai nell’Enryakuji sul monte Hiei nei pressi della capitale nel 1213. Dôgen era molto perplesso di fronte al fatto che sebbene l’uomo sia dotato della natura-di-Buddha, debba ugualmente impegnarsi nella disciplina e nella pratica e ricercare l’illuminazione. Con i suoi dubbi irrisolti e colpito dal lassismo dei costumi dei monaci del monte Hiei, Dôgen nel 1214 andò in cerca del maestro Kôin a Onjôji (Miidera) il centro Tendai rivale nella provincia di Ômi. Kôin mandò Dôgen da Eisai, il fondatore della scuola Rinzai e sebbene non sia certo se Dôgen riuscisse a incontrarlo fu molto influenzato da lui. -

Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Mindfulness Studies Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-6-2020 Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Meill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meill, Kyung Peggy, "Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā" (2020). Mindfulness Studies Theses. 29. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mindfulness Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ i Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Kim Meill Lesley University May 2020 Dr. Melissa Jean and Dr. Andrew Olendzki DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ ii Abstract A literary work provides a window into the world of a writer, revealing her most intimate and forthright perspectives, beliefs, and emotions – this within a scope of a certain time and place that shapes the milieu of her life. The Therīgāthā, an anthology of 73 poems found in the Pali canon, is an example of such an asseveration, composed by theris (women elders of wisdom or senior disciples), some of the first Buddhist nuns who lived in the time of the Buddha 2500 years ago. The gathas (songs or poems) impart significant details concerning early Buddhism and some of its integral elements of mental and spiritual development. -

Bowz Liturgy 2011.Corrected

Boundless Way Zen LITURGY BOOK SECOND EDITION _/\_ All buddhas throughout space and time, All honored ones, bodhisattva-mahasattvas, Wisdom beyond wisdom, Maha Prajna Paramita. Page 1 Notation ring kesu (bowl gong) muffle kesu (bowl gong) ring small bell 123 ring kesu or small bell on 1st, 2nd, or 3rd repetition accordingly underlined syllables indicate the point at which underlined bells are rung 1 mokugyo (wooden drum) beat once after then on each syllable taiko (large drum) beat once after then in single or double beats -_^ notation for tonal chanting (mid-low-high shown in this example) WORDS IN ALL CAPS are CHANTED by chant-leader only [Words in brackets & regular case] are spoken by chant-leader only {Words in braces} are CHANTED or spoken or sung !by chant-leader only 1st time, and by everyone subsequently (words in parenthesis) are not spoken, chanted, or sung at all _/\_ ! place or keep hands palm-to-palm in gassho, or hold liturgy book in gassho -(0)-! place or keep hands in zazen mudra, or hold liturgy book open !with little fingers and thumbs on the front of the book and !middle three fingers on the back seated bow at end of chant, or after final repetition Beginning our sutra service I vow with all beings To join my voice with all voices And give life to each word as it comes. —Robert Aitken Language cannot reach it, hearing and seeing cannot touch it. In this single beam of illumination, you genuinely wander in practice. Use your vitality to enact this. -

Women & Buddha

Myoshu Agnes Jedrzejewska M.D., Ph.D. The female disciples of Buddha – an understand- ing of Shinran’s teachings for our present times. When my daughter was a student of the Yokohama Inter- national School, we both learned that in practically all Eng- lish handbooks of history of Japanese religions, Jodo Shin- shu has nowadays been labeled by the Japanese intellectuals as the most misogynist and most conservative tradition in Japanese society and culture (see, for an example, “A History of Japanese Religion ed. Kazuo Kasahara, 2001). Such an opinion, however unjust, seems to be popular enough to make many Japanese families to covert into Christianity. I do believe that openly discussing the problem is always better than to take comfort in pretending that we have no problem at all. Sakyamuni was born among very discriminating people of India with rigid understanding of karma. Nevertheless, He successfully taught them the truly universal religion of non- substantiality, of impermanence, of the cause of human suf- fering and of the way of attaining true happiness. The Buddhist truth embraced the whole physical world and the whole of human life into one fundamental concep- tion of universal equality. With such a sense of equality, Buddhism contradicted not only Hindu, but all other relig- ions of that time. Confusian antagonism to Buddhism was ultimately directed against the Buddhist idea of equality. Similarly, every hierarchic society must have problem with Buddhad- harma with respect to social ethics. Buddhism, which came to the Japanese archipelago from Korea and China, is based upon the Mahayana interpreta- tion of the Sakyamuni’s teaching. -

Catalog and Revised Texts and Translations of Gandharan Reliquary Inscriptions

Chapter 6 Catalog and revised texts and translations of gandharan reliquary inscriptions steFan baums the Gandharan reliquary inscriptions cataloged and addition to or in place of these main eras, regnal translated in this chapter are found on four main types years of a current or (in the case of Patika’s inscrip- of objects: relic containers of a variety of shapes, thin tion no. 12) recent ruler are used in dating formulae, gold or silver scrolls deposited inside reliquaries, and detailed information is available about two of the thicker metal plates deposited alongside reliquaries, royal houses concerned: the kings of Apraca (family and stone slabs that formed part of a stūpa’s relic tree in Falk 1998: 107, with additional suggestions in chamber or covered stone reliquaries. Irrespective Salomon 2005a) and the kings of Oḍi (family tree in of the type of object, the inscriptions follow a uniform von Hinüber 2003: 33). pattern described in chapter 5. Three principal eras In preparing the catalog, it became apparent that are used in the dating formulae of these inscriptions: not only new and uniform translations of the whole the Greek era of 186/185 BCE (Salomon 2005a); the set of inscriptions were called for, but also the texts Azes (= Vikrama) era of 58/57 BCE (Bivar 1981b);1 themselves needed to be reconstituted on the basis and the Kanishka era of c. 127 CE (Falk 2001). In of numerous individual suggestions for improvements made after the most recent full edition of each text. All these suggestions (so far as they could be traced) 1. -

Dhammapada 2: Appamada Vagga-Narada

Home Page Previous Chapter Next Chapter Chapter 2 Appamada Vagga Heedfulness (Text and Translation by Ven. Narada) 1. Appamado amatapadam pamado maccuno padam Appamatta na miyanti ye pamatta yatha mata. 21. 2. Etam visesato ��atva appamadamhi pandita Appamade pamodanti ariyanam gocare rata. 22. 3. Te jhayino satatika niccam dalhaparakkama Phusanti dhira Nibbanam yogakkhemam anuttaram. 23. THE HEEDLESS DIE; THE HEEDFUL DO NOT 1. Heedfulness 1 is the path to the deathless, 2 heedlessness is the path to death. e heedful do not die; 3 the heedless are like unto the dead. 21. 2. Distinctly understanding this (difference 4), the wise (intent) on heedfulness rejoice in heedfulness, delighting in the realm of the Ariyas. 5 22. 3. e constantly meditative, 6 the ever steadfast ones realize the bond-free, 7 supreme Nibbana. 8 23. Story A jealous queen Magandiya, caused an innocent rival of hers, Samavati, to be burnt alive. e king, hearing of the pathetic incident subjected Magandiya to a worse death. e monks wished to know which of the two was actually alive and which was actually dead. e Buddha explained that the heedless, like Magandiya, should be regarded as dead, while the heedful, like Samavati, should be regarded as alive. 4. Uññhanavato satimato sucikammassa nisammakarino Sa����atassa ca dhammajivino appamattassa yaso'bhivaóóhati. 24. THE ENERGETIC PROSPER 4. e glory of him who is energetic, mindful, pure in deed, considerate, self-controlled, right-living, and heedful steadily increases. 24. Story A rich but humble young man who pretended to be very poor, living like a labourer, was later elevated to a high position by the king. -

Okumura's Fukanzazengi Translations

Dogen Zenji’s Fukanzazengi - Universal recommendation of zazen for all people - A comparison of two versions (1233, 1244) both as translated by Shohaku Okumura Introduction Having lost both his parents when young, Dogen was brought up by a relative before taking ordination as a Tendai monk at the age of 13. At 17, he moved to Kennin-ji in Kyoto where he trained in Rinzai Zen under Myozen, receiving dharma transmission in 1221. In 1223, he sailed with Myozen to South China, both of them wanting to deepen their practice. Searching for a true master, in 1225 he eventually found Tendo Nyojo, abbot of Tiantong monastery, staying there for two years and “opening his wisdom eye”. After returning to Japan in 1227, Dogen re-entered Kennin-ji but left after quite a short time, disappointed. He said he didn’t specifically intend to found a new Zen school. Rather he wanted to spread the true teaching (zazen) - whereas scholarly study was more typical of Japanese Buddhist practice. Buddhist politics meant that he decided to beoame a wandering monk for some time before founding Kosho-ji near Uji, which he led for ten years (1233-43). The building of Eihei-ji began ten years before his death in 1253. The Fukanzazengi The first version of the Fukanzazengi dates from Dogen’s ‘wandering’ period (1227-31). In fact, several of his pivotal works including Bendowa - (1231), Maka Hannya Haramitsu, Genjokoan (both 1233) were written in this period when he either had no temple, or was just beginning to establish his monastic community. -

Turning Rage to Love

emotional release BY GERI LARKIN Turning Rage to Love Anger over relationship breakups, betrayals or abandonment can serve as a wise teacher on the spiritual path elationship rage is at an all-time high. Maybe some feisty women. One of them, Magandiya, while it's just that there are more of us on the planet. graceful in figure, beautiful in appearance, and charming All I know is this: Rage is completely painful. when she wanted to be, was also jealous and mean-spirit- Screaming, pushing, shoving, sulking, manip- ed. When she didn't like another one of his wives, she ulating, emotional blackmailing, silent smol- went after her big time, using relationship rage as her dering,R watching for ways to get even. All rage. And weapon. Her main target was Samavati, the king's uncontrollable: You never know where it will aim itself. favorite consort. Magandiya constantly came up with A week ago, a young woman, Flimbeth, asked to schemes aimed at stirring the king's wrath toward her speak to me following a Sunday-morning meditation competition. Once, Magandiya put a snake into the king's service. She was in tears. She wanted my advice about an favorite lute and covered the hole with a bunch of flow- incident that had happened to her during the week. She ers. When he picked up the lute.. .out came the snake. and her partner were driving down a street near her house When the king saw the snake, he was furious. when they suddenly noticed a couple having an argu- Deciding Magandiya was right, he finally lost it The ment The man started beating the woman, really beating king commanded Samavati to stand in front of him with her. -

Realizing Genjokoan

BUDDHISM “Dōgen’s masterpiece is beautifully translated and clarified in an realizing genjokoan “Masterful.” equally masterful way. An obvious labor of love based on many —Buddhadharma The key to dogen’s shobogenzo years of careful study, reflection, and practice that succeeds in bringing this profound text to life for us all.” Larry Rosenberg, author of Breath by Breath “An unequaled introduction to the writings of the great Zen master Eihei Dōgen that opens doors to Dōgen’s vast understanding for everyone from newcomer to adept.” Jisho Warner, co-editor of Opening the Hand of ought “Realizing Genjōkōan is a stunning commentary on the famous first chapter of Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō. Like all masterful commentaries, this one finds in the few short lines of the text the entire span of the Buddhist teachings. Okumura has been contemplating, studying, and teaching the Genjōkōan for many decades, which is evident in both the remarkable insight he brings to the text and the clarity with which he presents it.” Buddhadharma: e Buddhist Review “is book is a treasure. ough many quite useful translations of Genjōkōan are already available, as well as helpful commentaries, this book goes beyond. I have been considering Genjōkōan for thirty-five years, and still I enjoyed many helpful revelations in Okumur a realizing this book. For all people interested in Zen, this book will be a valuable and illuminating resource. Please enjoy it.” genjokoan from the foreword by Taigen Dan Leighton, editor and co-translator of Dōgen’s Extensive Record The key to dogen’s