Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Dharma Devices, Non-Hermeneutical Libraries, and Robot-Monks : Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism Rambelli, Fabio University of California, Santa Barbara : Professor of Japanese Religions and IFS Endowed Chair Shinto Studies https://doi.org/10.5109/1917884 出版情報:Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University. 3, pp.57-75, 2018-03. 九州大学文学 部大学院人文科学府大学院人文科学研究院 バージョン: 権利関係: Dharma Devices, Non- Hermeneutical Libraries, and Robot-Monks: Prayer Machines in Japanese Buddhism FABIO RAMBELLI T is a well-documented fact—albeit perhaps not their technologies for that purpose.2 From a broader emphasized enough in scholarship—that Japa- perspective of more general technological advances, it nese Buddhism, historically, ofen has favored and is interesting to note that a Buddhist temple, Negoroji Icontributed to technological developments.1 Since its 根来寺, was the frst organization in Japan to produce transmission to Japan in the sixth century, Buddhism muskets and mortars on a large scale in the 1570s based has conveyed and employed advanced technologies in on technology acquired from Portuguese merchants.3 felds including temple architecture, agriculture, civil Tus, until the late seventeenth century, when exten- engineering (such as roads, bridges, and irrigation sive epistemological and social transformations grad- systems), medicine, astronomy, and printing. Further- ually eroded the Buddhist monopoly on technological more, many artisan guilds (employers and developers advancement in favor of other (ofen competing) social of technology)—from sake brewers to sword smiths, groups, Buddhism was the main repository, benefciary, from tatami (straw mat) makers to potters, from mak- and promoter of technology. ers of musical instruments to boat builders—were more It should come as no surprise, then, that Buddhism or less directly afliated with Buddhist temples. -

Taking Care of the Dead in Japan, a Personal View from an European Perspective Natacha Aveline

Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline To cite this version: Natacha Aveline. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective. Chiiki kaihatsu, 2013, pp.1-5. halshs-00939869 HAL Id: halshs-00939869 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00939869 Submitted on 31 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline-Dubach Translation of the paper : N. Aveline-Dubach (2013) « Nihon no sôsôbijinesu to shisha no kûkan, Yoroppajin no me kara mite », Chiiki Kaihatsu (Regional Development) Chiba University Press, 8, pp 1-5. I came across the funeral issue in Japan in early 1990s. I was doing my PhD on the ‘land bubble’ in Tokyo, and I had the opportunity to visit one of the first —if not the first – large- scale urban renewal project involving the reconstruction of a Buddhist temple and its adjacent cemetery, the Jofuji temple 浄風寺 nearby the high-rise building district of West Shinjuku. The old outdoor cemetery of the Buddhist community had just been moved into the upper floors of the new multistory temple. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE Aotearoa New Zealand Centre for Earthquake Resilience Contents ___ Directors’ Report 3 Chair’s Report 4 About Us 5 Our Outcomes 6 Research Research overview 7 Technology platforms 8 Flagship programmes 9 Other projects 10 Scrap tyres find new lives as earthquake protection 11 How effective is insurance for earthquake risk mitigation? 13 Toward functional buildings following major earthquakes 15 Collaboration to Impact Preparing for quakes: Seismic sensors and early warning systems 17 What makes a resilient community? 19 Collaboration a key tool in natural hazard public education 21 Human Capability Development Connections through quakes: International researchers tour New Zealand 23 Research in Te Ao Māori 25 The QuakeCoRE postgraduate experience 27 Recognition highlights 29 Financials, Community and Outputs Financials 33 At a glance 34 Community 35 Publications 41 Directors’ Report 2019 ___ Te Hiranga Rū QuakeCoRE formed in 2016 with a vision of transforming the QuakeCoRE continues to exhibit collaborative leadership domestically and earthquake resilience of communities throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, and in internationally. We highlight the strong alignment achieved with the ‘Resilience to four years, we are already seeing important progress toward this vision through our Nature’s Challenges’ National Science Challenge, progress associated with our on- focus on research excellence, deep national and international collaborations, and going commitment to Mātauranga Māori, partnership research between the public human capability development. and private sectors through community participation in seismic sensor deployment, and also the ‘Learning from Earthquakes’ programme as an example of international In our fourth Annual Report we highlight several world-class research stories, opportunities to study New Zealand as a natural earthquake laboratory. -

The Dogen Canon D 6 G E N ,S Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1997 24/1-2 The Dogen Canon D 6 g e n ,s Fre-Shobogenzo Writings and the Question of Change in His Later Works Steven H eine Recent scholarship has focused on the question of whether, and to what extent, Dogen underwent a significant change in thought and attitudes in nis Later years. Two main theories have emerged which agree that there was a decisive change although they disagree about its timing and meaning. One view, which I refer to as the Decline Theory, argues that Dogen entered into a prolonged period of deterioration after he moved from Kyoto to Echizen in 1243 and became increasingly strident in his attacks on rival lineages. The second view, which I refer to as the Renewal Theory, maintains that Dogen had a spiritual rebirth after returning from a trip to Kamakura in 1248 and emphasized the priority of karmic causality. Both theories, however, tend to ignore or misrepresent the early writings and their relation to the late period. I will propose an alternative Three Periods Theory suggesting that the main change, which occurred with the opening of Daibutsu-ji/Eihei-ji in 1245, was a matter of altering the style of instruc tion rather than the content of ideology. At that point, Dogen shifted from the informal lectures (jishu) of the Shdbdgenzd,which he stopped deliver ing, to the formal sermons (jodo) in the Eihei koroku, a crucial later text which the other theories overlook. I will also point out that the diversity in literary production as well as the complexity and ambiguity of historical events makes it problematic for the Decline and Renewal theories to con struct a view that Dogen had a single, decisive break with his previous writings. -

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

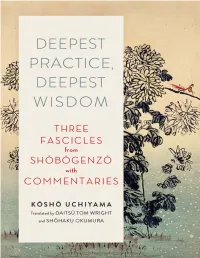

Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom

“A magnificent gift for anyone interested in the deep, clear waters of Zen—its great foundational master coupled with one of its finest modern voices.” —JISHO WARNER, former president of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association FAMOUSLY INSIGHTFUL AND FAMOUSLY COMPLEX, Eihei Dōgen’s writings have been studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. In Deepest Practice, Deepest Wisdom, Kshō Uchiyama, beloved twentieth-century Zen teacher, addresses himself head-on to unpacking Dōgen’s wisdom from three fascicles (or chapters) of his monumental Shōbōgenzō for a modern audience. The fascicles presented here from Shōbōgenzō, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, include “Shoaku Makusa” or “Refraining from Evil,” “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” or “Practicing Deepest Wisdom,” and “Uji” or “Living Time.” Daitsū Tom Wright and Shōhaku Okumura lovingly translate Dōgen’s penetrating words and Uchiyama’s thoughtful commentary on each piece. At turns poetic and funny, always insightful, this is Zen wisdom for the ages. KŌSHŌ UCHIYAMA was a preeminent Japanese Zen master instrumental in bringing Zen to America. The author of over twenty books, including Opening the Hand of Thought and The Zen Teaching of Homeless Kodo, he died in 1998. Contents Introduction by Tom Wright Part I. Practicing Deepest Wisdom 1. Maka Hannya Haramitsu 2. Commentary on “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” Part II. Refraining from Evil 3. Shoaku Makusa 4. Commentary on “Shoaku Makusa” Part III. Living Time 5. Uji 6. Commentary on “Uji” Part IV. Comments by the Translators 7. Connecting “Maka Hannya Haramitsu” to the Pāli Canon by Shōhaku Okumura 8. Looking into Good and Evil in “Shoaku Makusa” by Daitsū Tom Wright 9. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Japanese Gardens at American World’S Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıv | Number ı | Fall 2008 Essays: The Long Life of the Japanese Garden 2 Paula Deitz: Plum Blossoms: The Third Friend of Winter Natsumi Nonaka: The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones Marc Peter Keane: Listening to Stones Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Tea and Sympathy: A Zen Approach to Landscape Gardening Kendall H. Brown: Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan Book Reviews 18 Joseph Disponzio: The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Garden of Versailles By Ian Thompson Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition By Robert Pogue Harrison Calendar 22 Tour 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor times. Still observed is a Marc Peter Keane explains Japanese garden also became of interior and exterior. The deep-seated cultural tradi- how the Sakuteiki’s prescrip- an instrument of propagan- preeminent Wright scholar tion of plum-blossom view- tions regarding the setting of da in the hands of the coun- Anthony Alofsin maintains ing, which takes place at stones, together with the try’s imperial rulers at a in his essay that Wright was his issue of During the Heian period winter’s end. Paula Deitz Zen approach to garden succession of nineteenth- inspired as much by gardens Site/Lines focuses (794–1185), still inspired by writes about this third friend design absorbed during his and twentieth-century as by architecture during his on the aesthetics Chinese models, gardens of winter in her narrative of long residency in Japan, world’s fairs. -

Pratica E Illuminazione in Dôgen

ALDO TOLLINI Pratica e illuminazione in Dôgen Traduzione di alcuni capitoli dello Shôbôgenzô PARTE PRIMA INTRODUZIONE A DÔGEN La vita e le opere di Dôgen Dôgen fu uno dei più originali pensatori e dei più importanti riformatori religiosi giapponesi. Conosciuto col nome religioso di Dôgen Kigen o Eihei Dôgen, nel 1227 fondò la scuola Sôtô Zen, una delle più importanti e diffuse scuole buddhiste giapponesi che ancora oggi conta moltissimi seguaci. Fondò il monastero di Eiheiji nella prefettura di Fukui e scrisse lo Shôbôgenzô (1231/1253, il "Tesoro dell’occhio della vera legge"), diventato un classico della tradizione buddhista giapponese. Pur vivendo nel mezzo della confusione della prima parte dell’era Kamakura (1185-1333) egli perseguì con grande determinazione e profondità l’esperienza religiosa buddhista. Nacque a Kyoto da nobile famiglia, forse figlio di Koga Michichika (1149-1202) una figura di primo piano nell'ambito della corte. Rimase orfano da bambino facendo diretta esperienza della realtà dell’impermanenza, che diventerà un concetto chiave del suo pensiero. Entrò nella vita monastica come monaco Tendai nell’Enryakuji sul monte Hiei nei pressi della capitale nel 1213. Dôgen era molto perplesso di fronte al fatto che sebbene l’uomo sia dotato della natura-di-Buddha, debba ugualmente impegnarsi nella disciplina e nella pratica e ricercare l’illuminazione. Con i suoi dubbi irrisolti e colpito dal lassismo dei costumi dei monaci del monte Hiei, Dôgen nel 1214 andò in cerca del maestro Kôin a Onjôji (Miidera) il centro Tendai rivale nella provincia di Ômi. Kôin mandò Dôgen da Eisai, il fondatore della scuola Rinzai e sebbene non sia certo se Dôgen riuscisse a incontrarlo fu molto influenzato da lui.