Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schulhoffs Flammen

ERWIN SCHULHOFF Zur Wiederentdeckung seiner Oper „Flammen“ Kloster-Sex, Nekrophilie, alles eins Schulhoffs "Flammen". Entdeckung im "Don Juan"-Zyklus des Theaters an der Wien. Am Anfang war das Ich. Dann das Es. Und das Überich erst, lieber Himmel, da hat sich die Menschheit etwas eingebrockt, als sie alle Dämme brechen ließ und den Kaiser wie den Lieben Gott gute Männer sein ließen. Nichts klärt uns über die Befindlichkeit der Sigmund- Freud-Generation besser auf als die Kunst der Ära zwischen 1900 und 1933, ehe die Politik - wie zuvor schon in der sowjetischen Diktatur - auch in 9. August 2006 SINKOTHEK Deutschland die ästhetischen Koordinatensysteme diktierte. Beobachtet man in Zeiten, wie die unsre eine ist, die diversen sexuellen, religiösen und sonstigen Wirrnisse, von denen die damalige Menschheit offenbar fasziniert war, fühlt man sich, wie man im Kabarett so schön sang, "apres". Sex im Kloster, Nekrophilie, alles eins. Tabus kennen wir nicht mehr; jedenfalls nicht in dieser Hinsicht. Das Interesse an einem Werk wie "Flammen", gedichtet von Max Brod frei nach Karel Josef Benes, komponiert von dem 1942 von den Nationalsozialisten ermordeten Erwin Schulhoff, ist denn auch vorrangig musikhistorischer Natur. Es gab 9. August 2006 SINKOTHEK mehr zwischen Schönberg und Lehar als unsere Schulweisheit sich träumen lässt. Erwin Schulhoff war ein Meister im Sammeln unterschiedlichster Elemente aus den Musterkatalogen des Im- wie des Expressionismus. Er hatte auch ein Herz für die heraufdämmernde Neue Sachlichkeit, ohne deshalb Allvater Wagner zu verleugnen. Seine "Flammen", exzellent instrumentiert mit allem Klingklang von Harfe, Glocke und Celesta, das jeglichen alterierten Nonenakkord wie ein Feuerwerk schillern und glitzern lässt, tönen mehr nach Schreker als nach Hindemith - auch wenn das einleitende Flötensolo beinahe den keusch-distanzierten Ton der "Cardillac"- Musik atmet. -

Schreker Franz

SCHREKER FRAZ Compositore tedesco (Monaco di Baviera 23 III 1878 - Berlino 21 III 1934) 1 Schreker studiò composizione a Vienna insieme a Robert Fuchs e Hermann Graedener e violino con Sigismund Bachrich e Joseh Rosé. Fondatore (1908), e più tardi anche direttore (1911) del coro filarmonico di Vienna, nel 1912 fu nominato professore di composizione all'Accademia di musica. Dal 1920 fu direttore della Musikhochschule a Berlino, e negli anni compresi tra il 1922 e il 1933 diresse una classe di composizione all'Accademia prussiana delle arti di Berlino. Schreker fu amico di Schonberg e di Berg ed ebbe fra i suoi rilievi Alois Haba ed Ernest Krenek e fu uno dei compositori più celebri del suo tempo. Per numero di rappresentazioni delle sue opere superò addirittura Richard Strauss. Nel 1933 il regime nazista lo privò di tutte le cariche. Schreker è stato il compositore più popolare di un'opera fortemente influenzata dalla psicanalisi e basata sul patetismo di soggetti da cui traspaiono conflitti sessuali carichi di implicazioni simboliche. Al tempo stesso, è stato il maestro di un'espressività timbrica dell'orchestra che sfrutta a fondo le risorse di un cromatismo dal colore fortemente caratteristico e massimamente espressivo. 2 DER FERNE KLANG Tipo: (Il suono lontano) Opera in tre atti Soggetto: libretto proprio Prima: Francoforte, Stadtoper, 18 agosto 1912 Cast: Grete (S), Fritz (T), il dottor Vigelius (B), un comico (Bar), il conte (Bar), il cavaliere (T), Rudolf (B), una vecchia (Ms), il vecchio Graumann (B), sua moglie (Ms), l’oste (B), Mizi (S), Milly (Ms), Mary (S), una spagnola (A), il barone (B) Autore: Franz Schreker (1878-1934) Der ferne Klang è la seconda opera di Franz Schreker, ma la prima ad approdare sulle scene teatrali, dato che la precedente, Flammen (1902), era stata presentata soltanto in una ridotta esecuzione concertistica, con l’autore stesso al pianoforte. -

Maggie Jones Junior Recital, Spring 2017

Department of Music, Theatre and Dance Fulton School of Liberal Arts A Junior Recital given by Maggie Jones, Mezzo-Soprano Special Guests Syed Jaffery, Tenor John Wixted, Tenor From the studio of Dr. John Wesley Wright Accompanied by Veronica Tomanek In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in Music - Vocal Performance Sunday, May 14, 2017 Holloway Hall, Great Hall 5 p.m. www.salisbury.edu PROGRAM PROGRAM Ridente la calma (Armida) , K. 210a .... attr. to/arr. by W. A. Mozart; music by Josef Myslive ček (1737-1781) Ridente la calma Contented Calm Poet Unknown Translation by John Wesley Wright Ridente la calma nell’alma si desti, Contented calm in the soul awakens itself, Nè resti un segno di sdegno e timor. Neither a sign of anger nor fear remains. Tu vieni frattanto a stringer, mio bene, You come in the meantime to tighten, my dear, Le dolci catene si grate al mio cor. The sweet chains that are pleasing to my heart. Als Luise die Briefe ihres ungetreuen Liebhabers verbrannte, K. 520 .............. W. A. Mozart Abendempfindung, K. 523 (1756-1791) Als Luise die Briefe ihres As Louise Burned the Letter ungetreuen Liebhabers verbrannte of Her Faithless Lover Poem by Gabriele von Baumberg Translation by John Wesley Wright Erzeugt von heisser Phantasie, Produced by hot fantasy, In einer schwärmerischen Stunde In a rapturous hour brought Zur Welt gebrachte - geht zu Grunde, To the world - go to the ground (Die!), Ihr Kinder der Melancholie! You children of melancholy! Ihr danket Flammen euer Sein. You may thank flames for your existence. -

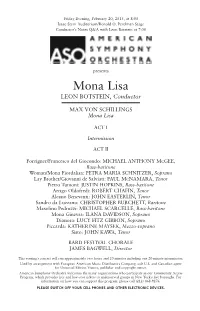

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Der Schatzgräber

1 DER SCHATZGRÄBER Oper in einem Vorspiel, vier Aufzügen und einem Nachspiel von Franz Schreker Der König..........................................................Hoher Bass Die Königin ......................................................Stumme Rolle Der Kanzler.......................................................Tenor Der Graf (Herold des zweiten Aufzugs) ...........Bariton Der Magister (des Königs Leibarzt) .................Bass Der Narr ............................................................Tenor Der Vogt............................................................Bariton Der Junker.........................................................dunkel gefärbter Bariton (oder hoher Bass) Elis, ein fahrender Sänger und Scholar.............Tenor Der Schultheiß ..................................................Bass Der Schreiber ....................................................Tenor Der Wirt ............................................................Bass Els, dessen Tochter ...........................................Sopran Albi, dessen Knecht ..........................................lyrischer Tenor Ein Landsknecht................................................Bass (tief) Erster Bürger.....................................................Tenor Zweiter Bürger..................................................Bariton Dritter Bürger....................................................Bass Erste alte Jungfer...............................................Mezzosopran Zweite alte Jungfer............................................Mezzosopran -

Christian Gerhaher, Baritone Gerold Huber, Piano

Tuesday, October 29, 2019 at 7:30 pm Mahler Songs Christian Gerhaher, Baritone Gerold Huber, Piano ALL-MAHLER PROGRAM Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (1883–85) Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz Selections from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (1887–1898) Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht? Ablösung im Sommer Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald Um schlimme Kinder artig zu Machen Rheinlegendchen Der Schildwache Nachtlied Intermission Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Alice Tully Hall, Starr Theater Adrienne Arsht Stage White Light Festival The White Light Festival 2019 is made possible by The Shubert Foundation, The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Mitsubishi Corporation (Americas), Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.), Inc., Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater, Culture Ireland, The Joelson Foundation, Sumitomo Corporation of Americas, The Harkness Foundation for Dance, J.C.C. Fund, Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of New York, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Patrons and Lincoln Center Members Endowment support is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance Lead Support for Great Performers provided by PGIM, the global investment management business of Prudential Financial, Inc. Additional Support for Great Performers is provided by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, The Shubert Foundation, The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Patrons and Lincoln Center Members Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund Endowment support is also provided by UBS Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. -

5178 Bookl:Layout 1 06.05.2013 12:03 Uhr Seite 1 5178 Bookl:Layout 1 06.05.2013 12:03 Uhr Seite 2

5178 bookl:Layout 1 06.05.2013 12:03 Uhr Seite 1 5178 bookl:Layout 1 06.05.2013 12:03 Uhr Seite 2 FRANZ SCHREKER (1878-1934) DER FERNE KLANG Oper in drei Aufzügen / Opera in 3 Acts Text: Franz Schreker - Gesamtaufnahme / Complete Recording - Grete GABRIELE SCHNAUT Fritz THOMAS MOSER Der alte Graumann VICTOR VON HALEM Frau Graumann BARBARA SCHERLER Der Wirt JOHANN WERNER PREIN Altes Weib JULIA JUON Ein Schauspieler HANS HELM Dr. Vigelius SIEGMUND NIMSGERN Milli / Kellnerin: Barbara Hahn · Mizzi / Ein Mädchen: Gudrun Sieber · Mary / Choristin: Gertrud Ottenthal Ein Individuum: Rolf Appel · Erster Chorist: Peter Haage · Der Graf: Roland Hermann Der Chevalier: Robert Wörle · Der Baron / Zweiter Chorist / Der Polizist: Gidon Saks · Rudolf: Claudio Otelli RIAS KAMMERCHOR · RUNDFUNKCHOR BERLIN (Einstudierung / Chorus Master: Dietrich Knothe) RADIO-SYMPHONIE-ORCHESTER BERLIN GERD ALBRECHT (Dirigent / conductor) Co-Produktion: RIAS Berlin - CAPRICCIO ©+P 1991 / 2013 CAPRICCIO, 1010 Vienna, Austria Made in Austria www.capriccio.at 3 5178 bookl:Layout 1 06.05.2013 12:03 Uhr Seite 3 CD 1 ERSTER AUFZUG / ACT ONE [1] Vorspiel …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4:02 1. SZENE / SCENE 1 [2] „Du willst wirklich fort, Fritz“ (Grete, Fritz) …………………………………………………………………. 2:10 [3] „Ein hohes, hehres Ziel schwebt mir vor Augen“ (Grete, Fritz) …………………………………………. 5:37 [4] „Hörst du, wie sie toben“ (Grete, Fritz) …………………………………………………………………….. 2:06 2. SZENE / SCENE 2 [5] „Frau Mama zu Hause?“ (Die Alte, Grete) ………………………………………………………………… 2:10 3. SZENE / SCENE 3 [6] „Was weinst denn?“ (Mutter, Grete) ………………………………………………………………………. 1:36 4. SZENE / SCENE 4 [7] „Nur herein, meine Herren“ ………………………………………………………………………………….. 7:23 (Graumann, Wirt, Schauspieler, Grete, Vigelius, Mutter, Chor) 5. SZENE / SCENE 5 [8] „Fräulein sollten sich‘s überlegen“ (Wirt, Mutter, Grete) …………………………………………………. -

Don Giovanni“-Aufführung Großartige Sängerinnen Und Sänger Und Gleich Zwei Unserer NDR Ensembles, Die NDR Radiophilharmonie Und Den NDR Chor, Erleben

5. NDR Klassik Open Air WolfgangDon Amadeus Giovanni Mozart 25. August 2018 GRUSSWORT Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, gerne begrüße ich Sie zum 5. NDR Klassik Open Air, einem musi- kalischen Ereignis, das Hannover auch am heutigen Abend wieder einen einzigartigen Glanz verleihen und Tausende Menschen zusammenführen wird. Ein Open Air live vor Ort im Maschpark, präsentiert im NDR Fernsehen heute ab 21.45 Uhr, im Stream auf NDR.de und im Hörfunk auf NDR Kultur. Sie werden in dieser „Don Giovanni“-Aufführung großartige Sängerinnen und Sänger und gleich zwei unserer NDR Ensembles, die NDR Radiophilharmonie und den NDR Chor, erleben. Zudem freue ich mich sehr über eine besondere Premiere beim NDR Klassik Open Air: Erstmals wird Lutz Marmor der exzellente Chefdirigent der NDR Radiophilharmonie, Andrew Intendant des NDR Manze, diesen Abend leiten. Das mit unseren Partnern, der Stadt Hannover und Hannover Concerts, ausgerichtete NDR Klassik Open Air ist inzwischen ein Opernereignis, das weit über die Gren- zen Hannovers und des NDR Sendegebiets hinausstrahlt und auch in Fachkreisen auf große Anerkennung stößt. Klassische Musik wird hier auf höchstem Niveau und auf ebenso stimmungsvolle wie eindringliche Weise einem breiten, vielfältigen Publikum ver- mittelt und fasziniert Klassik-Einsteiger wie Opernkenner gleicher- maßen. Ich wünsche Ihnen einen spannenden und bewegenden Abend mit Mozarts wunderbarem „Don Giovanni“! Ihr Lutz Marmor GRUSSWORT 02|03 Liebe Besucherinnen und Besucher, es ist wieder so weit: Das NDR Klassik Open Air wird heute Abend einmal mehr eine ganz besondere Atmosphäre in den Maschpark direkt am Rathaus und mitten in Hannovers City zaubern. Als kulturelles Großereignis ist dieses Highlight im hannoverschen Kultur-Sommer inzwischen fest verankert. -

Christopher Hailey

Christopher Hailey: Franz Schreker and The Pluralities of Modernism [Source: Tempo, January 2002, 2-7] Vienna's credentials as a cradle of modernism are too familiar to need rehearsing. Freud, Kraus, Schnitzler, Musil, Wittgenstein, Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka conjure up a world at once iridescent and lowering, voluptuously self-indulgent and cooly analytical. Arnold Schoenberg has been accorded pride of place as Vienna's quintessential musical modernist who confronted the crisis of language and meaning by emancipating dissonance and, a decade later, installing a new serial order. It is a tidy narrative and one largely established in the years after the Second World War by a generation of students and disciples intent upon reasserting disrupted continuities. That such continuities never existed is beside the point; it was a useful and, for its time, productive revision of history because it was fueled by the excitement of discovery. Revision always entails excision, and over the decades it became increasingly obvious that this narrative of Viennese modernism was a gross simplification. The re-discovery of Mahler was the first bump in the road, and attempts to portray him as Schoenberg's John the Baptist were subverted by the enormous force of Mahler's own personality and a popularity which soon generated its own self-sustaining momentum. In recent years other voices have emerged that could not be accommodated into the narrative, including Alexander Zemlinsky, Franz Schmidt, Egon Wellesz, Karl Weigl, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and most vexing of all Franz Schreker. Long banished out of hand, Schreker was subsequently marginalized as a late Romantic and allotted a mini-orbit of his own. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 8-2019 The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff Sara Marie Schuhardt Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Schuhardt, Sara Marie, "The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff" (2019). Dissertations. 590. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/590 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 SARA MARIE SCHUHARDT ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE FLUTE WORKS OF ERWIN SCHULHOFF A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Sara Marie Schuhardt College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music August 2019 This Dissertation by: Sara Marie Schuhardt Entitled: The Flute Works of Erwin Schulhoff has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Performing and Visual Arts in School of Music Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ______________________________________________________ Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Research Advisor ______________________________________________________ James Hall, D.M.A., Committee Member _______________________________________________________ -

Erwin Schulhoffs Flammen

Erwin Schulhoffs Flammen Die Genesis der Oper und einige analytische Betrachtungen Jirˇí David The reflection of Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) in secondary literature up to now consists of two major approaches: on the one hand he is perceived as a “Modemusiker” composing music influenced by jazz, dadaism and other avant-garde tendencies of the 1920s, on the other hand as a composer who reacted actively to the social situation and manifested his inclination to the left side of the political spectrum (this approach is based mainly on his compositions from the 1930s). Die Flammen is the only opera by Schulhoff who finished it at the turn of his two composing phases (completed in 1929, the premiere took place in 1932). Die Flammen stems from the context of musical drama between the two World Wars which is characterised by the loss of a clear canon of musical means. The libretto (created in 1922- 1924) corresponds with the expressionistic drama of the beginning of the 1920s including effects of dramatic alienation. Nevertheless, Schulhoff’s compositional style in this work is not in perfect accordance with the definition of musical expressionism. Unperiodical melodic ideas are covered by polyharmony and instrumentation with important timbre function. Schulhoff achieves this not only by the use of complicated harmonies, but also by the work with atonal intervallic structures and periodical lines which points out the constructivic features of his composing. Another analytical impulse represents the semantical work with jazz. In this opera jazz is not used as an element of renewal for European music like at the beginning of the 1920s.