Christopher Hailey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

Schreker Franz

SCHREKER FRAZ Compositore tedesco (Monaco di Baviera 23 III 1878 - Berlino 21 III 1934) 1 Schreker studiò composizione a Vienna insieme a Robert Fuchs e Hermann Graedener e violino con Sigismund Bachrich e Joseh Rosé. Fondatore (1908), e più tardi anche direttore (1911) del coro filarmonico di Vienna, nel 1912 fu nominato professore di composizione all'Accademia di musica. Dal 1920 fu direttore della Musikhochschule a Berlino, e negli anni compresi tra il 1922 e il 1933 diresse una classe di composizione all'Accademia prussiana delle arti di Berlino. Schreker fu amico di Schonberg e di Berg ed ebbe fra i suoi rilievi Alois Haba ed Ernest Krenek e fu uno dei compositori più celebri del suo tempo. Per numero di rappresentazioni delle sue opere superò addirittura Richard Strauss. Nel 1933 il regime nazista lo privò di tutte le cariche. Schreker è stato il compositore più popolare di un'opera fortemente influenzata dalla psicanalisi e basata sul patetismo di soggetti da cui traspaiono conflitti sessuali carichi di implicazioni simboliche. Al tempo stesso, è stato il maestro di un'espressività timbrica dell'orchestra che sfrutta a fondo le risorse di un cromatismo dal colore fortemente caratteristico e massimamente espressivo. 2 DER FERNE KLANG Tipo: (Il suono lontano) Opera in tre atti Soggetto: libretto proprio Prima: Francoforte, Stadtoper, 18 agosto 1912 Cast: Grete (S), Fritz (T), il dottor Vigelius (B), un comico (Bar), il conte (Bar), il cavaliere (T), Rudolf (B), una vecchia (Ms), il vecchio Graumann (B), sua moglie (Ms), l’oste (B), Mizi (S), Milly (Ms), Mary (S), una spagnola (A), il barone (B) Autore: Franz Schreker (1878-1934) Der ferne Klang è la seconda opera di Franz Schreker, ma la prima ad approdare sulle scene teatrali, dato che la precedente, Flammen (1902), era stata presentata soltanto in una ridotta esecuzione concertistica, con l’autore stesso al pianoforte. -

Complete Catalogue 2006 Catalogue Complete

COMPLETE CATALOGUE 2006 COMPLETE CATALOGUE Inhalt ORFEO A – Z............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Recital............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................82 Anthologie ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................89 Weihnachten ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................96 ORFEO D’OR Bayerische Staatsoper Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................99 Bayreuther Festspiele Live ...................................................................................................................................................................................................109 -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

Program Book

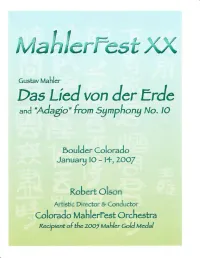

I e lson rti ic ire r & ndu r Schedule of Events CHAMBER CONCERTS Wednesday, January 1.O, 2007, 7100 PM Boulder Public Library Canyon Theater,9th & Canyon Friday, January L3, 7 3O PM Rocky Mountain Center for Musical Arts, 200 E. Baseline Rd., Lafayette Program: Songs on Chinese andJapanese Poems SYMPOSIUM Saturday, January L7, 2OO7 ATLAS Room 100, University of Colorado-Boulder 9:00 AM - 4:30 PM 9:00 AM: Robert Olson, MahlerFest Conductor & Artistic Director 10:00 AM: Evelyn Nikkels, Dutch Mahler Society 11:00 AMrJason Starr, Filmmaker, New York City Lunch 1:00 PM: Stephen E Heffiing, Case Western Reserve University, Keynote Speaker 2100 PM: Marilyn McCoy, Newburyport, MS 3:00 PMr Steven Bruns, University of Colorado-Boulder 4:00 PM: Chris Mohr, Denver, Colorado SYMPHONY CONCERTS Saturday, January L3' 2007 Sunday,Janaary L4,2O07 Macky Auditorium, CU Campus, Boulder Thomas Hampson, baritone Jon Garrison, tenor The Colorado MahlerFest Orchestra, Robert Olson, conductor See page 2 for details. Fundingfor MablerFest XXbas been Ttrouid'ed in ltartby grantsftom: The Boulder Arts Commission, an agency of the Boulder City Council The Scienrific and Culrural Facilities Discrict, Tier III, administered by the Boulder County Commissioners The Dietrich Foundation of Philadelphia The Boulder Library Foundation rh e va n u n dati o n "# I:I,:r# and many music lovers from the Boulder area and also from many states and countries [)AII-..]' CAMEI{\ il M ULIEN The ACADEMY Twent! Years and Still Going Strong It is almost impossible to fully comprehend -

CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei Conductor

SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Antonin Dvořák SympHONy NO.9, ‘FROm THE NEw wORlD’ Jean Sibelius FINlANDIA CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei conductor 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Jean Sibelius Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Finlandia Finlandia, Op 26 9’ Antonin Dvořák A brief trip to Finland is all that is required to grasp the legendary status that Jean Sibelius has acquired in his home nation. From his long-time home, Ainola, which has become a national Symphony No. 9, ‘From the New world’ museum, it is a mere 30 minute drive to Sibelius park in Helsinki, where sits the Sibelius monument. Budding Finnish musicians attend the Sibelius Academy, partake in the International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition and perform his symphonies in Sibelius Hall. Until the introduction of the euro, his portrait was on the Finnish 100 mark bill and Finland’s 1. Finlandia Jean Sibelius .....................................................................................................................................................[7.50] national Flag Day is now held on his birthday. But how did a musician and composer become a national hero, a position usually reserved for generals, freedom fighters and politicians? Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95, ‘From the New World’ Antonin Dvořák 2. I. Adagio - Allegro molto ...............................................................................................................................................[11.42] e answer lies with Finlandia, Sibelius’ love letter to the Finnish nation. -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

JUNE 2014 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 JUNE 2014 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer, 11th June sees the 150th anniversary of the birth of Richard Strauss and we have already seen a good sprinkling of new releases and re-issues appear in celebration this year. Thielemann’s new Elektra for DG is probably the highest-profile release this month, featuring a magnificent cast that includes Rene Pape and Anne Schwanewilms. Sadly, we hadn’t yet managed to obtain a preview copy at the time of going to print, but it certainly looks very promising! DG are also issuing a deluxe LP-sized boxset of Karajan’s analogue Strauss recordings this month that will feature 11 CDs, plus the entire contents on a single Blu-ray Audio. As is the trend at the moment, it will be a limited edition set packed full of extra material including photos and original liner notes. See p.2 for more information. Continuing with the Strauss theme, you may also like to take a look at the listing we have compiled of recordings from various independent labels. This covers 3½ pages (pp.10-13) and features some truly great titles. A good opportunity to fill in gaps in the library! Away from Strauss, other things to point out are a further batch of Most Wanted Recitals from Decca, featuring wonderful discs from the likes of Siepi, Nilsson, Souzay, Carreras etc. Harmonia Mundi are issuing another 10 titles in their HM Gold series - top recordings moved from their full-price catalogue down to mid-price. -

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Der Schatzgräber

1 DER SCHATZGRÄBER Oper in einem Vorspiel, vier Aufzügen und einem Nachspiel von Franz Schreker Der König..........................................................Hoher Bass Die Königin ......................................................Stumme Rolle Der Kanzler.......................................................Tenor Der Graf (Herold des zweiten Aufzugs) ...........Bariton Der Magister (des Königs Leibarzt) .................Bass Der Narr ............................................................Tenor Der Vogt............................................................Bariton Der Junker.........................................................dunkel gefärbter Bariton (oder hoher Bass) Elis, ein fahrender Sänger und Scholar.............Tenor Der Schultheiß ..................................................Bass Der Schreiber ....................................................Tenor Der Wirt ............................................................Bass Els, dessen Tochter ...........................................Sopran Albi, dessen Knecht ..........................................lyrischer Tenor Ein Landsknecht................................................Bass (tief) Erster Bürger.....................................................Tenor Zweiter Bürger..................................................Bariton Dritter Bürger....................................................Bass Erste alte Jungfer...............................................Mezzosopran Zweite alte Jungfer............................................Mezzosopran -

Wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt

BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Geflohen - verstummt - wiederentdeckt. Der Komponist Berthold Goldschmidt GESPRÄCHSKONZERT DER REIHE MUSICA REANIMATA AM 22. NOVEMBER 2016 IN BERLIN BESTANDSVERZEICHNIS DER MEDIEN VON UND ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT IN DER ZENTRAL- UND LANDESBIBLIOTHEK BERLIN INHALTSANGABE KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Noten Seite 3 Aufnahmen auf CD Seite 4 Aufnahmen in der Naxos Music Library Seite 6 SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR ÜBER BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT Seite 7 LEGENDE Freihand Bestand im Lesesaal frei zugänglich Magazin Bestand für Leser nicht frei zugänglich, Bestellung möglich Außenmagazin Bestand außerhalb der Häuser, Bestellung möglich AGB Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Blücherplatz 1, 10961 Berlin – Kreuzberg Berlin-Studien im Haus BStB (Berliner Stadtbibliothek) BStB Berliner Stadtbibliothek, Breite Str. 30-36, 10178 Berlin – Mitte Naxos Music Library Streamingportal mit klassischer Musik –- sowohl an den Datenbank-PCs der ZLB als auch (mit Bibliotheksausweis) von zu Hause nutzbar 2 KOMPOSITIONEN VON BERTHOLD GOLDSCHMIDT NOTEN Mediterranean songs : for tenor and orchestra = Gesänge vom Mittelmeer / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, c 1996. - 83 Seiten. HPS 1294 Exemplare: Standort Außenmagazin AGB Signatur 008/000 009 519 (No 139 Golds 1) Passacaglia opus 4 for large orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, 1998. - 1 Studienpartitur (22 Seiten). - ISMN M-060-10791-7 Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur 108/000 052 355 (No 147 Golds 1) String quartet no 2 : for string quartet [Noten] / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London : Boosey & Hawkes, [1991]. - 1 Partitur (42 Seiten) ; 31 cm. - Anmerkungen des Komponisten in Deutsch und Englisch Exemplare: Standort Freihand AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 2 String quartet no. 4 (1992) / Berthold Goldschmidt. - London [u.a.] : Boosey & Hawkes, 1994. - 20 Seiten Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 190 Golds 1 [Sinfonien, Nr. -

Robyn Archer 4-15 July

GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS ROBYN ARCHER 4-15 JULY European Cabaret really began in Paris in the 1880s and While the word cabaret has been then rapidly spread to Vienna at the fin de siècle, thence to stretched over the last few decades to Zurich, St Petersburg, Barcelona, Munich and Berlin, cover comedy, review, variety and where it coincided with the rise of national socialism and burlesque, there have been recent sniffs provided a necessary platform for voicing concern and of a return to something more akin to the criticism. Que Reste-t’Il starts with songs from the 1880s form’s noble origins, with Tim Minchin’s in Paris, and Dancing on the Volcano covers that brief rapid response to George Pell as a good period when Berlin cabaret was at first light-headed with example. Perhaps as the times again relief after World War I, and then traced the dramatic become more fraught, more complex, descent into despair and horror. The power of serious more difficult to understand and to poets and composers to record such histories is negotiate, ‘ the art of small forms’ (as undeniable, and reinforces the words of Brecht’s poem: Peter Alternberg described cabaret) will come into its own again. My young son asks Will there be singing in the bad times? Robyn Archer AO Yes, there will be singing About the bad times When the cabaret form crossed into English language- speaking countries, it tended to morph into something A NOTE FROM more polite, such as revue, and its bite was less at politics and corruption, and more to social mores and foibles.