Dealing with Inequality: Analysing Gender Relations in Melanesia And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Pacific Beats PDF

Connected South Pacific Beats Level 3 by Veronika Meduna 2018 Overview This article describes how Wellington designer Rachael Hall developed a modern version of the traditional Tongan lali. Called Patō, Rachael’s drum keeps the traditional sound of a lali but incorporates digital capabilities. Her hope is that Patō will allow musicians to mix traditional Pacific sounds with modern music. A Google Slides version of this article is available at www.connected.tki.org.nz This text also has additional digital content, which is available online at www.connected.tki.org.nz Curriculum contexts SCIENCE: Physical World: Physical inquiry and Key Nature of science ideas physics concepts Sound is a form of energy that, like all other forms of energy, can be transferred or transformed into other types of energy. Level 3 – Explore, describe, and represent patterns and trends for everyday examples of physical phenomena, Sound is caused by vibrations of particles in a medium (solid, such as movement, forces … sound, waves … For liquid, or gas). example, identify and describe the effect of forces (contact Sound waves can be described by their wavelength, frequency, and non-contact) on the motion of objects … and amplitude. The pitch of a sound is related to the wavelength and frequency – Science capabilities long or large vibrating objects tend to produce low sounds; short or small vibrating objects tend to produce high sounds. This article provides opportunities to focus on the following science capabilities: The volume of a sound depends on how much energy is used to create the sound – louder sounds have a bigger amplitude but the Use evidence frequency and pitch will be the same whether a given sound is Engage with science. -

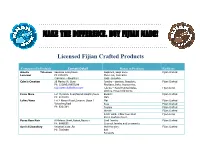

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

JBH the Art of the Drum

THE ART OF THE DRUM: THE RELIGIOUS AND SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC OF DRUMMING AND DRUM CRAFTING IN FIJI, JAPAN, INDIA, MOROCCO AND CUBA JESSE BROWNER-HAMLIN THE BRISTOL FELLOWSHIP HAMILTON COLLEGE WWW.THEARTOFTHEDRUM.BLOGSPOT.COM AUGUST 2007 – AUGUST 2008 2 In the original parameters of my Bristol Fellowship, I aspired to investigate the religious and spiritual dynamic of drumming and drum crafting in Fiji, Japan, India, Morocco, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago. As any academic will attest, field research tends to march to beat of its own drum, if you will. The beauty of my fellowship was that I could have conducted the research in just about any country in the world. Music is everywhere; and moreover, drums are the oldest instrument known to man. Along the way, I modestly altered the itinerary: in the end, I conducted research in Fiji, Japan, India, Western Europe, Morocco and Cuba. It truly was a remarkable experience to have full autonomy over my research: I am infinitely grateful that the Bristol Family and Hamilton College (represented by Ginny Dosch) gave me the freedom to modify my itinerary as I saw fit. To be successful while conducting field research, you need to be flexible. While several of my hypotheses from my proposal were examined and tested, I often found myself in unscripted situations. The daily unpredictability of the fellowship is what makes it such a profound and exciting experience, as every day is an adventure. With the blessing of technology, this fellowship was carried out in “real time.” Because I actively maintained a website, www.theartofthedrum.blogspot.com, my research and multimedia were posted almost instantaneously, and thus, my family and friends back in the States could read about my experiences, see my pictures and watch my videos. -

The Oxford Democrat

how s rou* inmr • la lb# (omlr opara of Th* .Mikalo Hla Imperial lligbnaaa u>« T« H«k*, U> MM rlMI, km«i *nl Litw A lunula* u»»r or kMBlMt ■MITlMfnl" A nobler taak tbu makleg a*M BlMi rlveraof kunlwi urrlatil mpttm. If king or laymaa. con 1.1 take npon hi«a» Th« Hear among the iwlnu «u contid md tba Kitrct of all a man a eall Impnl- mi, ao'l U« tkatcn arr ui to ooa l»d»f that If om'i liver la In an ngly condition of dlaconteat, ton* one a bead will be muh.il before il|kt •' to lb* llow a your Uvaf I la niilriltot aa to ■ |««"| llffin alwl «l hit* Inquiry Arc yoa a tear or angel iMiRICl a *bk n«il« *11 Ihlnj* l.Tl KAI. »o J i «•*•« la If* of CARD BKIOADK. ^.irati' >'W»d«jr. thr ■' ORPARTMKNT m* I4M il, which THK POSTAL ■ pD|*l« •la* A • Ira tntli*rt.-* >b u In h.-r fK In t&a wrf» inter am- hi-* uv-nl ««<4i him lla 1.1, of tb« th**p ktllail I .tail, » M put Niao-uatba "paranaaailaia*." • IU4 »h• «*, or Irlnwl -h-- -a•> (o (aal Comv itmi ■« R bat tt« 4<«« iikirl AFFAIR iMd Uu<«|h tla«l.air anH •tl<Vik fMI ihr actloM for divorce. tba cartaia l*c Wutn V> kta> Ntiptil laat A FAMILY »r« Oar rrp.>n of tbr Kalr. w**h, Ml tkM) IUi|i llufi haial tb» of Itrittad I |rf«i rat ail h • I m*>. -

Australian CD Project

'tX) rlrt r,,'tl,l ,,1n,,,. \t l(tt "Bring the Past to Present": Recording and Reviving Rotuman Music via a Collaborative RotumaniFijian/ AustralianCD Project Karl Neuenfeldt Abilru(t This ltqter etplores a recordingpr<tjett tltut led to CDs dtx'utnetrtittgRrturtrttrr tnusi- cul per.fortnan<'esand ntusi<'practitt' in Snva,Fiji. The pro.jectn:us u t'ollulxtrution befw'eenthe Rottmnn tliusporiccttnunuttit,-, the'Ot'euniu Cetilre.lor the Art,sund Cul- ture ut tlk Universitl'oJ'the South PaL'itit und a nrusic-busedresearcher Jrotn Austru- liu. It usesdescriptitsn, unaltsis und ethnogruplt,-Io e.rpktrethe role oJ'digitaltechnol- og,ies;tht' role untl ewtlutiottol ntusiL'in tliasporiccotnnuuilies in Australia and Fi.ii: tlrc benefit.sutttl L'hallenges of tollulxtrative trunsildtionalmusitul researchpr()je(ts: antl tlrc role oJnusit reseon'hers us rttusit producers. "l think it is veryimportant to know aboutthe old songsand the new ones as wcll. I am a loverof singingand I loveto singchurch hymns and the traditional songs as well. It is also irnportantbecausc I can alwaystell my grandchildlc-nabout the songsof the past anclpresent and thcy might know rvhenthey -qrowup whcthcr anythinghas changed."(Sarote Fesaitu. eldest fernale member of the ChurchwardChlpel's Rotu- man Choir. Suva.Fiji 2004) In recent years an ernerging discourse in music-based studies has coalesced around the interrelationshipsbetween digital recording technologies,cross-cultural collaborative researchproJects and rnusic-researchersoperating as music producers, artistsor entr€preneurs.Greene and Porcello (2005:2) use the term "wired sound" for this phenomenon and discourseand provide the following sunllrary: Recordingstudios have become. among othc'r things. sponge-like centers where the world's soundsare quickly and continuallvabsorbed. -

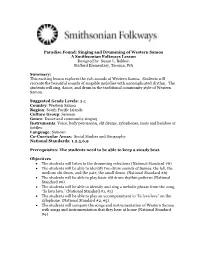

Singing and Drumming of Western Samoa a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Susan L

Paradise Found: Singing and Drumming of Western Samoa A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Susan L. Bakken Stafford Elementary, Tacoma, WA Summary: This exciting lesson explores the rich sounds of Western Samoa. Students will recreate the beautiful sounds of singable melodies with uncomplicated rhythm. The students will sing, dance, and drum in the traditional community style of Western Samoa. Suggested Grade Levels: 3-5 Country: Western Samoa Region: South Pacific Islands Culture Group: Samoan Genre: Dance and community singing Instruments: Voice, body percussion, slit drums, xylophones, mats and bamboo or bottles. Language: Samoan Co-Curricular Areas: Social Studies and Geography National Standards: 1,2,5,6,9 Prerequisites: The students need to be able to keep a steady beat. Objectives The students will listen to the drumming selections (National Standard #6) The students will be able to identify two drum sounds of Samoa, the lali, the medium slit drum, and the pate, the small drum. (National Standard #6) The students will be able to play basic slit drum rhythm patterns (National Standard #6) The students will be able to identify and sing a melodic phrase from the song, “Ia lava lava.” (National Standard #1, #5) The students will be able to play an accompaniment to “Ia lava lava” on the xylophone. (National Standard #2, #5) The students will compare the songs and instrumentation of Western Samoa with songs and instrumentation that they hear at home (National Standard #9) Materials: Smithsonian Folkways listening excerpts -

Touring Pacific Cultures by Kalissa Alexeyeff, John Taylor

TOURING PACIFIC CULTURES TOURING PACIFIC CULTURES EDITED BY KALISSA ALEXEYEFF AND JOHN TAYLOR Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Alexeyeff, Kalissa, author. Title: Touring Pacific cultures / Kalissa Alexeyeff and John Taylor. ISBN: 9781921862441 (paperback) 9781922144263 (ebook) Subjects: Culture and tourism--Oceania. Tourism--Oceania. Cultural industries--Oceania. Arts--Oceania--History. Oceania--Cultural policy. Other Creators/Contributors: Taylor, John, 1969- author. Dewey Number: 338.47910995 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image adapted from Culture for Sale, 2014. Still from video installation by Yuki Kihara. Photography by Rebecca Stewart. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents List of Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xvii Notes on Images and Orthography . .. xix 1 . Departures and Arrivals in Touring Pacific Cultures . 1 John Taylor and Kalissa Alexeyeff 2 . Hawai‘i: Prelude to a Journey . 29 Selina Tusitala Marsh 3 . Darkness and Light in Black and White: Travelling Mission Imagery from the New Hebrides . 33 Lamont Lindstrom 4 . Tourism . 59 William C . Clarke 5 . The Cruise Ship . 61 Frances Steel 6 . Pitcairn and the Bounty Story . 73 Maria Amoamo 7 . Guys like Gauguin . 89 Selina Tusitala Marsh 8 . Statued (stat you?) Traditions . 91 Selina Tusitala Marsh 9 . Detouring Kwajalein: At Home Between Coral and Concrete in the Marshall Islands . -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandardm argins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Rotuma: Sprache Und Geschichte

Rotuma: Sprache und Geschichte von Hans Schmidt i Inhaltsverzeichnis Liste der Tabellen v Liste der Karten viii Liste der Diagramme viii Erklärung der Abkürzungen ix 1. Vorwort 1 2. Einleitung 2 2.1 Geographie und Demographie 4 2.2 Soziolinguistik 7 2.2.1 Die soziolinguistische Situation auf Rotuma 7 2.2.1.1 Sprachen 7 2.2.1.2 Orte und Mittel der Kommunikation 9 2.2.1.3 Lesestoff in rotumanischer Sprache 11 2.2.2 Die soziolinguistische Situation der Rotumaner in Fiji 12 2.3 Veränderung und Zukunft der Sprache 14 2.4 Verschiedene Schreibweisen 15 3. Synchrone Phonologie des Rotuma 16 3.1 Das Phoneminventar des Rotuma 18 3.1.1 Konsonanten 18 3.1.2 Vokale und ihre Anzahl 20 3.2 Die Entstehung der sekundären Vokale 25 3.2.1 Die Bildung der Kurzform 26 3.2.1.1 Wörter mit unbetonter letzter Silbe 29 3.2.1.2 Metathese 41 3.2.1.3 Metathese innerhalb eines Wortes - Komposita 42 3.2.2 Wörter, die in zwei und mehr Vokale auslauten 43 3.2.3 Wörter mit langen Vokalen im Auslaut 45 3.2.4 Weitere vokalverändernde Prozesse 45 3.2.4.1 Teilweise regressive Assimilation 46 3.2.4.2 Velarisierung 46 3.2.4.3 Fernwirkende Assimilation 48 3.2.4.4 e-Formen 48 3.2.5 Varianten der mittelhohen Vokale 48 3.2.6 Sonstige Varianten 50 4. Etymologische Analyse des Rotumanischen Wortschatzes 50 4.1 Dialektformen 50 4.2 Lehnwörter 51 4.2.1 Lehngut aus europäischen Sprachen 52 4.2.1.1 Frühe Entlehnungen 53 4.2.1.2 Entlehnungen im kirchlichen Sprachgebrauch 57 4.2.1.3 Moderne Entlehnungen 58 4.2.1.4 Phonologische Einbürgerung englischer Lehnwörter 60 4.2.1.4.1 Konsonanten -

The Pacific Author(S): Matt K

The Pacific Author(s): Matt K. Matsuda Reviewed work(s): Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No. 3 (June 2006), pp. 758-780 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/ahr.111.3.758 . Accessed: 11/04/2012 00:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and American Historical Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org AHR Forum The Pacific MATT K. MATSUDA IN THINKING OF SEAS AND OCEANS, Fernand Braudel famously illuminated his Med- iterranean by imagining multiple civilizations joined by trade and cultural exchange; his Annales approach of a longue dure´e built upon archaeological and ecological evidence shaped a brilliant chronicle of kingdoms and powers. Yet as he noted of his subject itself, the Mediterranean was not even a single sea, but rather “a complex of seas, and the seas are broken up by islands, a tempest of peninsulas ringed by insistent coastlines.”1 To establish the project, he knew, “the question of boundaries is the first to be encountered.” Defining the “Pacific” is an equally daunting challenge. -

Fishery Council to Obama

Students from Pacific Horizons School were Buckle up! among the over 100 people who were at the Tauese P.F. Sunia Ocean Center in Utulei on FATALITIES CRASHES Friday for the screening of Jean Michel Cous- teau’s film: “Swains Island: One of the Last 2 517 Jewels on the Planet”. LOCAL HIGHWAYS LOCAL HIGHWAYS Cousteau said, “I remember my father 01-01-14 TO DATE 01-01-14 TO DATE telling me that people protect what they love; and I kept saying, ‘How can you protect some- thing you don’t understand?’” He said the National Monument of Amer- OFFICE OF highway SAFETY ican Samoa can be a destination for learning more about our life support system (the ocean),” and this understanding, he says will open minds DOE Director fields up to make much better decisions “than I ever questions over the did make growing up…” [photo: B. Chen] start of school… 3 ONLINE @ SAMOANEWS.COM E ono sii to- C M togi o laisene Y K i le OMV… DAILY CIRCULATION 7,000 10 PAGO PAGO, AMERICAN SAMOA MONDAY, AUGUST 25, 2014 $1.00 Samuelu: ASVB Fishery Council to Obama — budget a “joke” Abandon Marine Monument POTENTIALLY CATASTROPHIC CONSEQUENCES FOR U.S FISHING INDUSTRY by Joyetter Feagaimaali’i-Luamanu, Samoa News Reporter While the American Samoa Visitors Bureau Director, by Fili Sagapolutele, Samoa News Correspondent (PICs), providing $21 million annually in funds David Vaeafe announced before the lawmakers last week Top leaders of the Western Pacific Regional shared by all the independent Pacific Islands that Virginia Samuelu was among the board member for the Fishery Management Council board of direc- Forum countries, which is in addition to the ASVB, Samuelu told Samoa News that’s not true, calling the tors say continuity of American Samoa as a payments made for fishing days. -

Neighborhood Listprice Address TN Mlsnum REALTOR® Name

ListPrice Address Neighborhood TN MlsNum BR/BA/½ REALTOR® Name Phone Time/Date Single Family $585,000 91-6221 Kapolei 417 FS 201623051 3/2/1 Shannon D. Severance, RA (808) 426-8772 2p to 5p Sep 18 RE/MAX Honolulu Central Condo/Townhouse $527,000 95-710 Kipapa 13 MILILANI AREA FS 201621651 3/2/0 Jennie CH Galera, RA (808) 222-8283 2p to 5p Sep 18 Pine Knoll Villas Vonlin Hawaii Real Estate $335,000 95-1050 Makaikai 6G MILILANI MAUKA FS 201622489 2/1/0 Karen M. Yamada, DR (808) 205-9742 2p to 4p Sep 18 Olaloa 1 808 Encore Realty $420,000 1124 Kilani 14L WAHIAWA AREA FS 201604693 3/2/1 Wayne S. Masuda, DR (808) 927-2372 2p to 5p Sep 17 The Parkside At Kilani Oahu Realty $420,000 1124 Kilani 14L WAHIAWA AREA FS 201604693 3/2/1 Wayne S. Masuda, DR (808) 927-2372 2p to 5p Sep 18 The Parkside At Kilani Oahu Realty $229,500 2069 California 14A WAHIAWA HEIGHT FS 201621682 2/1/0 Ginger B. Meyers, RA (808) 864-1639 2p to 5p Sep 18 Hidden Valley Ests West Beach Realty, Inc. $310,000 95-227 Waikalani A504 WAIPIO ACRES/WAI FS 201619384 2/1/0 Randy L. Prothero, DR (808) 384-5645 1p to 4p Sep 18 Waikalani Woodlands eXp Realty $305,000 95-2044 Waikalani C403 WAIPIO ACRES/WAI FS 201621774 3/2/0 Lynn M. Wilkinson, DR (808) 255-2113 2p to 5p Sep 18 Ridgecrest-Melemanu Vonlin Hawaii Real Estate Rental $2,400 95-215 Waioleka 60 MILILANI AREA LH 201616666 2/1/1 Ward Steven Nihiser, RA (808) 386-5639 2p to 5p Sep 18 Mililani Pinnacle 1 Aloha Properties, Inc.