Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

South Pacific Beats PDF

Connected South Pacific Beats Level 3 by Veronika Meduna 2018 Overview This article describes how Wellington designer Rachael Hall developed a modern version of the traditional Tongan lali. Called Patō, Rachael’s drum keeps the traditional sound of a lali but incorporates digital capabilities. Her hope is that Patō will allow musicians to mix traditional Pacific sounds with modern music. A Google Slides version of this article is available at www.connected.tki.org.nz This text also has additional digital content, which is available online at www.connected.tki.org.nz Curriculum contexts SCIENCE: Physical World: Physical inquiry and Key Nature of science ideas physics concepts Sound is a form of energy that, like all other forms of energy, can be transferred or transformed into other types of energy. Level 3 – Explore, describe, and represent patterns and trends for everyday examples of physical phenomena, Sound is caused by vibrations of particles in a medium (solid, such as movement, forces … sound, waves … For liquid, or gas). example, identify and describe the effect of forces (contact Sound waves can be described by their wavelength, frequency, and non-contact) on the motion of objects … and amplitude. The pitch of a sound is related to the wavelength and frequency – Science capabilities long or large vibrating objects tend to produce low sounds; short or small vibrating objects tend to produce high sounds. This article provides opportunities to focus on the following science capabilities: The volume of a sound depends on how much energy is used to create the sound – louder sounds have a bigger amplitude but the Use evidence frequency and pitch will be the same whether a given sound is Engage with science. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2015

Jan 15 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 161st birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 7 to Jan. 11. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was Alan Bradley, co-author of MS. HOLMES OF BAKER STREET (2004), and author of the award-winning "Flavia de Luce" series; the title of his talk was "Ha! The Stars Are Out and the Wind Has Fallen" (his paper will be published in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal). The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's Restaurant was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton and An- drew Joffe) entertained the audience with an updated version of "The Sher- lock Holmes Cable Network" (2000). The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Ser- pentine Muse last year: the winner (Jenn Eaker) received a certificate and a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. -

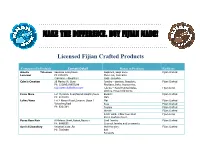

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Rotuma Wide Governments to Deal with the New Threats 14 May That Government Was Overthrown in a Mili Failed

Rotuma wide governments to deal with the new threats 14 May that government was overthrown in a mili failed. Facing the prospect of continuing instability tary coup led by Sitiveni Rabuka (FIJI COUPS). Fol and insistent demands by outsiders, Cakobau and lowing months of turmoil and delicate negotiations, other leading chiefs of Fiji ceded Fiji to Great Britain Fiji was returned to civilian rule in December 1987. on 10 October 1874 (DEED OF CESSION). A new constitution, entrenching indigenous domi Sir Arthur GORDON was appointed the first sub nance in the political system, was decreed in 1990, stantive governor of the new colony. His policies which brought the chiefs-backed Fijian party to and vision laid the foundations of modern Fiji. He political power in 1992. forbade the sale of Fijian land and introduced an The constitution, contested by non-Fijians for its 'indirect system' of native administration that racially-discriminatory provisions, was reviewed by involved Fijians in the management of their own an independent commission in 1996 (CONSTITUT affairs. A chiefly council was revived to advise the ION REVIEW IN FIJI), which recommended a more government on Fijian matters. To promote economic open and democratic system encouraging the forma development, he turned to the plantation system he tion of multi-ethnic governments. A new constitu had seen at first hand as governor of Trinidad and tion, based on the commission's recommendations, Mauritius. The Australian COLONIAL SUGAR was promulgated a year later, providing for the rec REFINING COMPANY was invited to extend its ognition of special Fijian interests as well as a consti operation to Fiji, which it did in 1882, remaining in tutionally-mandated multi-party cabinet. -

Rotumans in Australia and New Zealand: the Problem of Community Formation

NZPS 2(2) pp. 191-203 Intellect Limited 2014 journal of New Zealand & Pacific Studies Volume 2 Number 2 © 2014 Intellect Ltd Article. English language, doi: io.i386/nzps.2.2.i9i_i JAN RENSEL AND ALAN HOWARD University of Hawai'i at Manoa Rotumans in Australia and New Zealand: The problem of community formation ABSTRACT KEYWORDS As members of the Fiji polity, people from the isolated island of Rotuma have beenRotum a able to move freely about the archipelago, leading to stepwise-migration interna diaspora tionally, with Australia and New Zealand as primary destinations. Rotuman men cultural preservation engaged in the pearl-diving industry in the Torres Strait in the late nineteenth cultural identity century, who married local women, were among the first documented migrants to Australia Australia. Following World War II, a steady stream of Rotumans, many of them New Zealand married to white spouses, emigrated and formed communities in urban settings like Sydney, Brisbane, Auckland and elsewhere, where they have been remarka bly successful. Their very success in the workforce, along with high rates of inter marriage and dispersed households, makes getting together a challenging prospect, requiring strong motivation, effective leadership, and a commitment to preserving their Rotuman cultural heritage. Tire island of Rotuma is located on the western fringe of Polynesia, about 465 kilometres north of the main islands of Fiji. Politically, Rotuma was governed as part of the Colony of Fiji since its cession to Great Britain in 1881 and has been part of Fiji since the country's independence in 1970. Although its linguistic affiliations remain somewhat of an enigma (see Grace 1959; Schmidt 1.999), the culture of the island reveals a closer affinity with Samoa, 191 Jan Rensel |Alan Howard Tonga, Futuna and Uvea than with Fiji or the Melanesian islands to the west. -

A Midsummer Nights Dream 11 'T} S , O(;;)-2 by Wilham Shakespeare

A Midsummer NightS Dream 11 't} s , o(;;)-2 by WilHam Shakespeare ~ BAm~ Tiieater BRooKLYN AcADEMY oF Music Compa11y ~~~~~~~~~ \.. ~ , •' II I II Q ,\.~ I II 1 \ } ( "' '" \ . • • !I II'" r )DO I \ ., : \ I ~\ } .. \ ;; .; 'I' ... .. _:..,... 1t ; rJ ,.I •\ y v \ YOUR MONEY GROWS LIKE MAGIC AT THE THE DIME SAVINGS BANK DF NEW YORK -..1-..ett•O•C MANHATTAN • DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN • BENSONHURST • FLATBUSH CONEY ISLAND • KINGS PLAZA • VALLEY STREAM • MASSAPEQUA HUNTINGTON STATION TABLE OF Old CONTENTS Hungary "An authentic ~ ounpany~~~~~~~ Hungarian restaurant right here in Brooklyn" Beef Goulash, Ch1cken Papnka, St uffed Cabbage, Palacsinta and other traditional dishes " Live Piano Music Nightly" The Actors 5-8 PRE-T HEATRE AND AFTER THEATRE DINNER 142 Montague St., Bklyn . Hghts. Notes on the Play 9-14 625· 1649 Production Team 15 § The Staff 16 'R(!tauranb The Actors 17-19 tel: 855-4830 Contributors 20-21 UL8-2000 Board of Directors 22 open daily for lunch and dinner till 9 P. M. Italian and A m erican Cuisine special orders upon request Flowers, plants and fruit baskets for all occasions (212) 768-6770 25th Street & 768-0800 5th Avenue Deluxe coach service following DIRECTORY BAM Theater Company Directory of Facilities a nd Services Box Office: Monday 10 00 to &.00 Tue.day throu~h ~tur performances day 10 00 to Y 00 Sunday Performance limes only Lost ond ~o und : Telephone &36-4 150 Restroom: Operu We pick you up and take you back llouse Women .ond Men. Mezzanme level. HandKapp<.·d Or c h c~t r a level Ployh ou,e: Women Orchestra l~vcl ,\.1cn .'Ae1 (to Manhattan) 1.anme lt•vel llandocapped Orchestra level Lepercq Spucc: The BAMBus Express will pick-up BAM Theater Company Wom en ,,nd Men Tht•c.H e r level Public T ele phon es. -

Rotuma As a Hinterland Community

Home Page Howard-Rensel Papers Archives 2. Rotuma as a Hinterland Community Alan Howard [Published in Journal of the Polynesian Society 70:272-299, 1961] The island of Rotuma lies about three hundred miles to the north of the Fiji group, on the western fringe of Polynesia. [1] At present there are approximately three thousand Rotumans living on the island, and well over a thousand others reside in Fiji, with which Rotuma has been politically united since its annexation to the Crown in 1881. The island's geographical location places it very near to the intersection of the conventional boundaries of Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia, and traces of influence from each of these areas can be found in the racial composition, language and culture of the people. The bulk of the evidence points to a Polynesian orientation, however, and it may be regarded as an anomaly of history that Rotuma should have become politically united with Fiji, instead of with islands like Samoa, Tonga, Futuna and Wallis, to which a large number of Rotumans can still trace their heritage. Nevertheless, the Rotumans have made a successful adjustment to these circumstances and have managed to become an integral part of the social, economic and political life of the Colony of Fiji. From the standpoint of an anthropologist interested in the processes of urbanization, the Rotuman population offers an excellent opportunity for research. For one thing, the island is isolated, so that movement of people and goods is not continuous, but dependent upon ships which call at irregular and often widely spaced intervals. -

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: • Howard-Field Casting, (Los Angeles, London & Europe) 1993-2014 • Director of Feature Casting, Warner Bros. Studios, Los Angeles 1989-1993 • Howard-Field Casting ( London & Europe) 1983-1989 • Casting & Project Consultant RKO, London operations 1983-1985 • Associate Casting Director Royal Shakespeare Company, London 1977-1983 • Production Assistant to director/producer Martin Campbell, London 1975-1977 • Assistant to writer, Tudor Gates, Drumbeat Productions, London 1975-1977 FILMS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT FOR 2014/15: AMOK – Director: Kasia Adamik. Screenplay: Richard Karpala. Executive producer: Agnieszka Holland. Producers: Beata Pisula, Debbie Stasson - in development for spring 2015 WALKING TO PARIS – Director: Peter Greenaway, Producer: Kees Kasander and Julia Ton. Scheduled to commence pp February 2015 in Romania, Switzerland and France. THE WORLD AT NIGHT – Director: TBC. Screenplay: William Nicholson. Producer: Vanessa van Zuylen, (VVZ Presse, Paris, France), Matthias Ehrenberg, Jose Levy, (Cuatro Films Plus) Ibon Cormenzana, (Arcadia Motion Pictures), – in development to shoot Argentina and France Spring 2015. Daniel Bruhl attached. RACE – In association with Suzanne Smith Casting. Director: Stephen Hopkins. Filming Berlin and Canada, September 2014. Casting a selection of cameo roles from the UK AMERICAN MASSACRE – Director: TBC Producer: Emjay Rechsteiner (Staccato Films); Executive Producer: Harris Tulchin - in development for Spring 2015, shooting New Zealand and Canary Islands LITTLE SECRET (Pequeno Segredo) – Director: David Schurmann; Writer: Marcos Bernstein; Producers: Matthias Ehrenberg (Cuatro Films Plus), Joao, Roni (Ocean Films, Brazil), Emma Slade (Fire Fly Films, NZ), Barrie Osborn – in development to shoot Brazil, October 2014. Finnoula Flanagan attached THE BAY OF SILENCE: - Director: Mark Pellington; Screenwriter & Producer: Caroline Goodall, Executive Producer: Peter Garde. -

Issues of Concern to Rotumans Abroad

ISSUES OF CONCERN TO ROTUMANS ARROAD: A VIEW FROM THE ROTUMA WEBSITE Alan Howard Jan Rensel University of Hawaii at Manoa THE ISLAND OF ROTUMA is relatively remote, located 465 kilometers north of the northernmost island in the Fiji group, and only slightly closer to Futuna, its nearest neighbor. Rotuma has been politically affiliated with Fiji for more than a century, first as a British colony following cession in 1881 and since 1970 as part of the independent nation. Rotuma's people are, however, culturally and linguistically distinct, having strong historic relationships with Polynesian islands to the east, especially Tonga, Samoa, and Futuna. Today, approximately 85 percent of those who identify them selves as Rotuman or part-Rotuman live overseas, mostly on the island of Viti Levu in Fiji, but with substantial numbers in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and England. Although this article is based primarily on postings from the Rotuma Website, which was created by Alan Howard in 1996, it is informed by research begun by Alan in 1959 over a two-year period on the island of Rotuma and among Rotumans in Fiji. Jan's first visit was in 1987, and we have returned ten times since then for periods ranging from a week to six months. For the past two decades, we have also made multiple visits to all the major overseas Rotuman communities in addition to keeping in touch with Rotuman friends from around the globe via home visits, telephone, e-mail, and, most recently, Facebook. Over the years, we have published a number of articles concerning the Rotuman diaspora and Rotuman communities abroad (Howard 1961; Howard and Howard 1977; Howard Pacific Studies, Vol. -

Alan Howard, MA, Phd, FRIC (1929–2020): As I Knew Him

International Journal of Obesity (2020) 44:2343–2346 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00683-4 OBITUARY In Memoriam: Alan Howard, MA, PhD, FRIC (1929–2020): as I knew him George A. Bray1 Received: 14 August 2020 / Revised: 19 August 2020 / Accepted: 3 September 2020 / Published online: 9 October 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Howard, who worked in a mill, and Elsie (née Atkins), who was a tailor. After his father lost a finger in an accident at the mill, he used the compensation money to build up a tailoring business with his wife. After World War II they opened the Victory Café in Norwich. Alan was educated at City of Norwich grammar school where he played chess for the Norfolk and Norwich Club. At age 17, in 1946, he won the newly created Junior Championship Cup. He was also a 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: keen photographer with his own darkroom. Howard won a place at Downing College in Cambridge, England in 1948 where he studied Natural Sciences. He was elected to the Arthur Paul Saint Scholarship at Downing College in July 1952, a scholarship he held for 2 years. Dr. Howard’s PhD was approved on 30 Nov 1954 for research on ‘the reaction of diazonium compounds with amino acids and proteins and its application to serological problems’.He received both his MA and PhD on 22 Jan 1955. Dr. Howard’s academic career was spent entirely at Cambridge University in England where he worked in various departments, including the Medical Research Council Unit of Nutrition (also known as “the Dunn”), the Department of Pathology and the Department of Medicine.