ME 3-7-2013 Met Illustraties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangsawan Prampoewan Enlightened Peranakan Chinese Women from Early Twentieth Century Java

422 WacanaWacana Vol. Vol.18 No. 18 2No. (2017): 2 (2017) 422-454 Bangsawan prampoewan Enlightened Peranakan Chinese women from early twentieth century Java Didi Kwartanada ABSTRACT The end of the nineteenth century witnessed paradox among the Chinese in colonial Java. On one hand, they were prospering economically, but were nonetheless held in contempt by the Dutch, encountered legal discrimination and faced challenges if they wanted to educate their children in European schools. Their marginal position motivated them do their utmost to become “civilized subjects”, on a par with Europeans, but they were also inspired to reinvent their Chinese identity. This contribution will highlight role played by “enlightened” Chinese, the kaoem moeda bangsa Tjina. Central to this movement were the Chinese girls known to the public as bangsawan prampoewan (the noblewomen), who wrote letters the newspaper and creating a gendered public sphere. They also performed western classical music in public. Considering the inspirational impact of bangsawan prampoewan’s enlightening achievements on non-Chinese women, it is appropriate to include them into the narrative of the history of the nation’s women’s movements. KEYWORDS Chinese; women; modernity; progress; newspapers; Semarang; Surabaya; western classical music; Kartini. Didi Kwartanada studies history of the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, especially Java. He is currently the Director of the Nation Building Foundation (NABIL) in Jakarta and is preparing a book on the history of Chinese identity cards in Indonesia. His publications include The encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War (Leiden: Brill, 2009) as co-editor and contributor, and the most recent work Tionghoa dalam keindonesiaan; Peran dan kontribusi bagi pembangunan bangsa (3 vols; Jakarta: Yayasan Nabil, 2016) as managing editor cum contributor. -

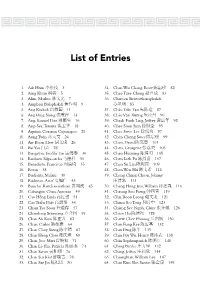

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Komunitas Tionghoa Di Solo: Dari Terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959)

Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo: Dari terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959) SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sastra Program Studi Sejarah Disusun Oleh : CHANDRA HALIM 024314004 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2008 2 3 4 MOTTO Keinginan tanpa disertai dengan tindakan adalah sia-sia. Sebaliknya ketekunan dan kerja keras akan mendatangkan keberhasilan yang melimpah. (Amsal 13:4) 5 HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Tiada kebahagiaan yang terindah selain mempersembahkan skripsi ini kepada : Thian Yang Maha Kuasa serta Para Buddha Boddhisattva dan dewa dewi semuanya yang berkenan membukakan jalan bagi kelancaran studiku. Papa dan Mama tercinta, serta adik-adikku tersayang yang selalu mendoakan aku untuk keberhasilanku. Om Frananto Hidayat dan keluarga yang berkenan memberikan doa restunya demi keberhasilan studi dan skripsiku. 6 ABSTRAK Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo: Dari terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959) Chandra Halim 024314004 Skripsi ini berjudul “Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo : Dari Terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959)“. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan dan menganalisis tiga permasalahan yang diungkapkan, yaitu sejarah masuknya Etnik Tionghoa di Solo, kehidupan berorganisasi Etnik Tionghoa di Solo dan pembentukan organisasi Chuan Min Kung Hui (CMKH) hingga berubah menjadi Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (PMS). Metode yang digunakan dalam penulisan skripsi ini adalah metode sejarah yang mencakup heuristik, kritik sumber, interpretasi, dan penulisan. Selain itu juga menggunakan metode wawancara sebagai sumber utama, dan studi pustaka sebagai sumber sekunder dengan mencari sumber yang berasal dari buku-buku, koran, dan majalah. Penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa keberadaan Tionghoa di Solo sudah ada sejak 1740, tepatnya ketika Solo dalam kekuasaan Mataram Islam. -

Dutch Commerce and Chinese Merchants in Java Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

Dutch Commerce and Chinese Merchants in Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 291 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki Dutch Commerce and Chinese Merchants in Java Colonial Relationships in Trade and Finance, 1800–1942 By Alexander Claver LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial‐NonDerivative 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC‐ND 3.0) License, which permits any noncommercial use, and distribution, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Front cover illustration: Sugar godown of the sugar enterprise ‘Assem Bagoes’ in Sitoebondo, East Java, ca. 1900. Collection Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV), Leiden (image code: 6017). Back cover illustration: Five guilder banknote of De Javasche Bank, 1934. Front side showing a male dancer of the Wayang Wong theatre of Central Java. Back side showing batik motives and a text in Dutch, Chinese, Arabic and Javanese script warning against counterfeiting. Design by the Dutch artist C.A. Lion Cachet. Printed by Joh. Enschedé en Zonen. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Claver, Alexander. Dutch commerce and Chinese merchants in Java : colonial relationships in trade and finance, 1800-1942 / by Alexander Claver. -

Liem Thian Joe's Unpublished History of Kian Gwan

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No.2, September 1989 Liem Thian Joe's Unpublished History of Kian Gwan Charles A. COPPEL* Studies on the role of the overseas Chinese sue the talent for writing which was already in the economies of Southeast Asia are rare evident in his schoolwork. A short ex enough, despite their generally acknowledged perience as a trader in Ngadiredjo soon con importance. This has been particularly true vinced him, however, that he should seek his of Indonesia, and consequently it is a matter livelihood as a writer. of some interest to discover an unpublished His career in journalism seems to have history of Kian Gwan (Oei Tiong Ham Con begun in the 1920's when he joined the staff of cern), the biggest and longest-lasting Chinese the Semarang peranakan Chinese daily, Warna business of all in Indonesia. Further interest Warla (although there is some suggestion that is aroused by the fact that the manuscript was he also contributed to the Jakarta daily, Per written by the late Liem Thian Joe, the well niagaan, at this time). In the early 1930's, he known Semarang journalist and historian. moved from Warna Warta to edit the Semarang This combination gives us promise of insights daily, Djawa Tengah (and its sister monthly into the firm itself, the Oei family which Djawa Tengah Review). In later years he established it and built it up, and the history of was also a regular contributor to the weekly the Chinese of Semarang where its original edition of the Jakarta newspaper, Sin PO.2) office was founded. -

Denys Lombard and Claudine Salmon

Is l a m a n d C h in e s e n e s s Denys Lombard and Claudine Salmon It is worth pausing for a moment to consider the relationships that were able to exist between the expansion of Islam in the East Indies and the simultaneous formation of "Chinese" communities. These two phenomena are usually presented in opposition to one another and it is pointless here to insist on the numerous conflicting accounts, past and present.* 1 Nevertheless, properly considered, it quickly becomes apparent that this is a question of two parallel developments which had their origins in the urban environment, and which contributed to a large extent to the creation of "middle class" merchants, all driven by the same spirit of enterprise even though they were in lively competition with one another. Rather than insisting once more on the divergences which some would maintain are fundamental—going as far as to assert, against all the evidence, that the Chinese "could not imagine marrying outside their own nation," and that they remain unassimilable—we would like here to draw the reader's attention to a certain number of long-standing facts which allow a reversal of perspective. Chinese Muslims and the Local Urban Mutation of the 14th-15th Centuries No doubt the problem arose along with the first signs of the great urban transformation of the 15th century. The fundamental text is that of the Chinese (Muslim) Ma Huan, who accompanied the famous Admiral Zheng He on his fourth expedition in the South Seas (1413-1415), and reported at the time of their passage through East Java that the population was made up of natives, Muslims (Huihui), as well as Chinese (Tangren) many of whom were Muslims. -

Perkembangan Pendidikan Anak-Anak Tionghoa Pada Abad 19 Hingga Akhir Orde Baru Di Indonesia

Perkembangan Pendidikan Anak-Anak Tionghoa Pada Abad 19 Hingga Akhir Orde Baru Di Indonesia Noor Isnaeni ABA BSI Jl. Salemba Tengah No.45 Jakarta Pusat [email protected] ABSTRACT - In the 19th century the Dutch East Indies government did not care about education for Chinese children. When the clothing, food and shelter were fulfilled, Chinese people began to think about their children's education. Finally, Chinese people made an association named THHK (Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan) on March 17, 1900. The purpose of this scientific writing is to find out how the development of the educational of Chinese children in the 19th century until the collapse of new era and what the Chinese people doing for the education of their children at that time. The research method used is the method of historical research, that is: heuristics, source criticism, interpretation and historiography. The main purpose of the establishment of schools THHK is to spread the religion of Confucius. By coming out Chinese schools established by the Chinese people, it caused that the Dutch East Indies government worried of the Chinese people and their offspring’s nationalism growing up. Therefore, the Dutch East Indies government found Holandsch Chineesche School (HCS) – it was built up for Chinese people with Dutch language as the main language. Key Words: development, education, childrens of chinese, in Indonesia. 1. PENDAHULUAN berusaha meningkatkan perdagangan antar Sejarah Indonesia mencatat bahwa sejak pulau dan mulailah terjadi perdagangan besar- abad ke-5 sudah ada orang Tionghoa yang besaran di Nusantara. Potensi dagang orang mengunjungi Nusantara. Salah satu orang Tionghoa sangat meresahkan pemerintah VOC Tionghoa yang mengunjungi Nusantara adalah yang pada saat itu mulai menjajah Nusantara. -

Prominent Chinese During the Rise of a Colonial City Medan 1890-1942

PROMINENT CHINESE DURING THE RISE OF A COLONIAL CITY MEDAN 1890-1942 ISBN: 978-94-6375-447-7 Lay-out & Printing: Ridderprint B.V. © 2019 D.A. Buiskool All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission of the author. Cover photo: Chinese festive gate in Kesawan, Medan 1923, on the occasion of the 25th coronation jubilee of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. Photo collection D.A. Buiskool PROMINENT CHINESE DURING THE RISE OF A COLONIAL CITY MEDAN 1890-1942 PROMINENTE CHINEZEN TIJDENS DE OPKOMST VAN EEN KOLONIALE STAD MEDAN 1890-1942 (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 11 november 2019 des middags te 4.15 uur door Dirk Aedsge Buiskool geboren op 8 februari 1957 te Hoogezand Sappemeer 3 Promotor: Prof. Dr. G.J. Knaap 4 Believe me, it is so. The beginning, and not the middle, is the right starting point. ’T is with a kopeck, and with a kopeck only, that a man must begin.1 1 Gogol, Nikol ai Dead Souls Translated by C. J. Hogarth, University of Adelaide: 2014: Chapter III. 5 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 1 EAST SUMATRA. THE FORMATION OF A PLANTATION ECONOMY. 29 1. East Sumatra: Historical Overview 32 1.1 East Sumatra until circa 1870 32 1.2 From Tobacco to Oil and Rubber 34 1.3 Migrant workers 38 1.4 Frontier society 43 1.5 Labour conditions on the plantations 44 1.6 Van den Brand’s manifesto 47 1.7 Labour inspection 48 Summary 50 CHAPTER 2 THE CITY OF MEDAN. -

Indo 92 0 1319755155 157

W omen an d M odernity: Reading the Femme Fatale in Early Twentieth-Century Indies Novels Elizabeth Chandra1 In colonial Indonesia, literary works written in Malay by Chinese authors were commonly denigrated as pulp fiction, and therefore deemed "un-literary," due to their affinity with stories of secrecy, scandal, sex, and crime.2 The sinister sensibilities of these novels supposedly ran counter to the ideal notion of literature as "beautiful writings," which the colonial government had attempted to introduce in the Netherlands Indies beginning in the second decade of the twentieth century.3 This article offers a close examination of one such novel, Si Riboet atawa Boenga Mengandoeng Ratjoen: Soeatoe Tjerita jang Betoel Terdjadi di Soerabaja Koetika di Pertengahan Taon 1916, jaitoe Politie Opziener Coenraad Boenoe Actrice Constantinopel jang Mendjadi Katjinta'annja (Riboet, or the Venomous Flower: A True Story which Occurred in Soerabaja in Mid- 11 thank those who read and commented on this essay at different stages: Tamara Loos, John Wolff, Sylvia Tiwon, Benedict Anderson, and Indonesia's editors and anonymous reviewer. Any remaining errors are, of course, my own. 2 Claudine Salmon, Literature in Malay by the Chinese of Indonesia: A Provisional Annotated Bibliography (Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 1981). See also Elizabeth Chandra, "National Fictions: Chinese-Malay Literature and the Politics of Forgetting" (PhD dissertation, University of California- Berkeley, 2006). 3 Balai Pustaka, Balai Pustaka Sewadjarnja, 1908-1942 (Djakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1948); Bureau voor de Volkslectuur, The Bureau of Popular Literature of Netherlands India: What It is and What It Does (Batavia: Bureau voor de Volkslectuur, 1930); D. -

Peran Etnis Tionghoa Pada Masa Pergerakan Nasional

PERAN ETNIS TIONGHOA PADA MASA PERGERAKAN NASIONAL: KAJIAN PENGEMBANGAN MATERI PEMBELAJARAN SEJARAH DI SEKOLAH MENENGAH ATAS Hendra Kurniawan Dosen Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah, FKIP, Universitas Sanata Dharma Alamat korespondensi: Jl. Affandi Mrican Tromol Pos 29 Yogyakarta Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research was aimed to describe the role of the Chinese community during the Indonesia’s national movement, to design the way of learning history in the senior high school, and to elaborate the importance of studying the role of the Chinese community during Indonesia’s national movement for the younger generation. This research uses historical and qualitative descriptive method using literature. The result shows that (1) Chinese community took importance roles in national struggling during Indonesia’s national movement; (2) The study of the Chinese community’s roles in the Indonesia’s national movement can be integrated into the way of learning history in senior high school; (3) Studying the roles of the Chinese community during the Indonesia’s national movement can develop the harmony in social life. Keywords: Tionghoa, pergerakan nasional, pembelajaran sejarah. 1. PENDAHULUAN Indonesiaan-nya rendah, dituduh memihak Belanda, dan hanya mementingkan keselamatan diri sendiri. Masyarakat Indonesia memiliki struktur yang Pemikiran seperti ini perlu diluruskan dengan unik. Nasikun (1984: 30) menyebutkan secara mengungkap berbagai peran dan keterlibatan etnis horizontal, masyarakat Indonesia memiliki kesatuan- Tionghoa dalam sejarah nasional Indonesia. kesatuan sosial atas dasar ikatan primordial, seperti Sejarah masyarakat Tionghoa jarang diangkat suku, agama, adat, daerah, hingga hubungan darah. atau hanya memiliki porsi kecil dalam konteks sejarah Secara vertikal, struktur masyarakat Indonesia nasional. Padahal orang Tionghoa tersebar dan dapat ditandai dengan adanya perbedaan antara lapisan atas ditemui di setiap kota dari Sabang sampai Merauke. -

Heritage, Conversion, and Identity of Chinese-Indonesian Muslims

In Search of New Social and Spiritual Space: Heritage, Conversion, and Identity of Chinese-Indonesian Muslims (Op Zoek naar Nieuwe Plek, Maatschappelijk en Geestelijk: Erfgoed, Bekering en Identiteit van Chinese Moslims in Indonesië) (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 24 februari 2012 des ochtends te 12.45 uur door Syuan-Yuan Chiou geboren op 24 september 1967 te Pingtung, Taiwan Promotor: Prof.dr. M.M. van Bruinessen This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (ISIM), the Netherlands, the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (CCKF), Taiwan, and the Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies (CAPAS), RCHSS, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. About the author: CHIOU Syuan-yuan (邱炫元) is a sociologist, who is interested in exploring contemporary Indonesian Muslim society and Chinese-Indonesians. He obtains his PhD degree in Utrecht University, the Netherlands. He was involved in the International Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World at Leiden, the Netherlands, where he joined interdisciplinary projects, working on various issues of contemporary Islam in Africa, Middle East, Southeast Asia, and West Europe during 2001-2007. He has published several works about Chinese-Indonesian Muslims. -

CANDRA NAYA ANTARA KEJAYAAN MASA LALU DAN KENYATAAN SEKARANG (Hasil Penelitian Tahun 1994- 1998)

DIMENSI TEKNIK ARSITEKTUR Vol. 31, No. 2, Desember 2003: 88-101 CANDRA NAYA ANTARA KEJAYAAN MASA LALU DAN KENYATAAN SEKARANG (Hasil Penelitian tahun 1994- 1998) Naniek Widayati Staf Pengajar Jurusan Arsitektur – Universitas Tarumanagara Jakarta ABSTRAK Kedamaian bangunan kuno Candra Naya akhir-akhir ini terusik oleh adanya polemik, baik dari media cetak maupun elektronik. Hal ini terjadi karena adanya sebuah pernyataan yang dibuat oleh pemiliknya, yaitu PT Bumi Perkasa Permai kepada sebuah paguyuban Indonesia-Cina. Masalahnya adalah bahwa paguyuban tersebut berniat mendirikan sebuah museum Indonesia-Cina di TMII (Taman Mini Indonesia Indah) dan ingin mengajukan permohonan untuk memindahkan bangunan Candra Naya tersebut ke TMII, yang nantinya direncanakan untuk menjadi bagian dari bangunan museum tersebut. Tulisan ini berisi informasi, melalui proses pengamatan lapangan yang dibuat pada tahun-tahun yang lalu. Sifat dari tulisan ini adalah netral dan tidak memihak pada siapapun. Terima kasih pada PT Bumi Perkasa Permai yang telah memberikan kepada saya kesempatan untuk meneliti bangunan konservasi tersebut. Isi dari tulisan ini meliputi sejarah serta data proses perjalanan gedung tersebut. Juga usaha konservasi yang sudah dibuat, sampai krisis tahun 1998. Sesudah itu usaha tersebut terhenti. Kata kunci: Candra Naya, Bangunan Kuno, Arsitektur Cina di Indonesia. ABSTRACT The peacefulness of Candra Naya ancient building has lately begun to be disturbed again because of many kinds of polemics on printed and electronic media as well as on millis. This happens because there is a present decision made by the owner, namely PT Bumi Perkasa Permai to Indonesian Chinese Fund. It happens that at present this Fund wants to build Indonesian Chinese Museum at TMII (Mini Beautiful Indonesian Park) and that Fund makes a request that it is allowed to move the Candra Naya building to TMII so that it can be a part of the Museum building.