Hitherto Unnoticed Coptic Papyrological Evidence for Early Arabic Alchemy*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Book Reviews

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 35, Number 2 (2010) 125 BOOK REVIEWS Rediscovery of the Elements. James I. and Virginia Here you can find mini-biographies of scientists, R. Marshall. JMC Services, Denton TX. DVD, Web detailed geographic routes to each of the element discov- Page Format, accessible by web browsers and current ery sites, cities connected to discoveries, maps (354 of programs on PC and Macintosh, 2010, ISBN 978-0- them) and photos (6,500 from a base of 25,000), a time 615-30793-0. [email protected] $60.00 line of discoveries, 33 background articles published by ($50.00 for nonprofit organizations {schools}, $40.00 the authors in The Hexagon, and finally a link to “Tables at workshops.) and Text Files,” a compilation probably containing more information than all the rest of the DVD. I will discuss this later, except for one file in it: “Background Before the launching of this review it needs to be and Scope.” Here the authors point out that the whole stated that DVDs are not viewable unless your computer project of visiting the sources, mines, quarries, museums, is equipped with a DVD reader. I own a 2002 Microsoft laboratories connected with each element, only became Word XP computer, but it failed. I learned that I needed possible very recently. Four recent developments opened a piece of hardware, a DVD reader. It can be installed the door: first, the fall of the Iron Curtain allowing easy inside the computer or attached externally. The former is access to Eastern Europe including Russia; second, the cheaper, in fact quite inexpensive, unless you have to pay universality of email and internet communication; third, for the installation. -

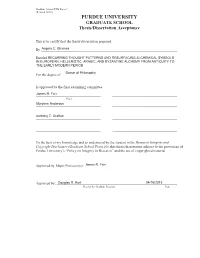

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Multiple Translations The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Table of Contents The Emerald Tablet of Hermes.........................................................................................................................1 Multiple Translations...............................................................................................................................1 History of the Tablet................................................................................................................................1 Translations From Jabir ibn Hayyan.......................................................................................................2 Another Arabic Version (from the German of Ruska, translated by 'Anonymous')...............................3 Twelfth Century Latin..............................................................................................................................3 Translation from Aurelium Occultae Philosophorum..Georgio Beato...................................................4 Translation of Issac Newton c. 1680........................................................................................................5 Translation from Kriegsmann (?) alledgedly from the Phoenician........................................................6 From Sigismund Bacstrom (allegedly translated from Chaldean)..........................................................7 From Madame Blavatsky.........................................................................................................................8 -

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 7 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) was supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 Number 6: Donald J. Mastronarde, Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides, 2017 Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity Olivier Dufault CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2019 by Olivier Dufault. -

The Reconstruction Concept of Musa Jabir Ibn Hayyan Thought: Study on Chemistry for Establishing Civilization in Islamic Integration of Science

The Reconstruction Concept of Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan Thought: Study on Chemistry for Establishing Civilization in Islamic Integration of Science Aminatul Husna Department of IPA Education, Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teacher Training State Islamic Institute of Religious Study Jember - Indonesia Correspondance; Email: [email protected] Abstract The background of this paper was declining of historical thinking of Islamic civilization in science. The aims of the research were to know: 1) how the concept of Jabir Bin Hayyan thought for developing chemistry; 2) how the application of Jabir Bin Hayyan's concept of thinking in the integration of Islamic science and technology; 3) how the restoration of chemistry to build civilization. This paper used library research by using descriptive analysis. Musa Jabir Bin Hayyan was a pioneer in modern science and inherited Alchemy. The work that is still used today such as reduction, sublimation, and distillation. Jabir Bin Hayyan creates alembic material that can turn wine into alcohol. This discovery is not necessarily abused into liquor. In contrast, alcohol production became a key process for developing a number of chemical industries during Islamic civilization. Alchemy has declined in the end of the 14th century and also as the lag progress of science in the Islamic world momentum, including chemistry. The decline of chemistry-science is the lack of moral support in Islamic civilization. Inserting the history and concepts of Muslim intellectual thought in science is the way to raise the age of Islamic civilization in present today. Integrating science with Islamic values needs to be applied. Because it can produce people who have intellectual and akhlakul karimah. -

Colour and Colorimetry Multidisciplinary Contributions

Colour and Colorimetry Multidisciplinary Contributions Vol. XI B Edited by Maurizio Rossi and Daria Casciani www.gruppodelcolore.it Regular Member AIC Association Internationale de la Couleur Colour and Colorimetry. Multidisciplinary Contributions. Vol. XI B Edited by Maurizio Rossi and Daria Casciani – Dip. Design – Politecnico di Milano Layout by Daria Casciani ISBN 978-88-99513-01-6 © Copyright 2015 by Gruppo del Colore – Associazione Italiana Colore Via Boscovich, 31 20124 Milano C.F. 97619430156 P.IVA: 09003610962 www.gruppodelcolore.it e-mail: [email protected] Translation rights, electronic storage, reproduction and total or partial adaptation with any means reserved for all countries. Printed in the month of October 2015 Colour and Colorimetry. Multidisciplinary Contributions Vol. XI B Proceedings of the 11th Conferenza del Colore. GdC-Associazione Italiana Colore Centre Français de la Couleur Groupe Français de l'Imagerie Numérique Couleur Colour Group (GB) Politecnico di Milano Milan, Italy, 10-11 September 2015 Organizing Committee Program Committee Arturo Dell'Acqua Bellavitis Giulio Bertagna Silvia Piardi Osvaldo Da Pos Maurizio Rossi Veronica Marchiafava Michela Rossi Giampiero Mele Michele Russo Christine de Fernandez-Maloigne Laurence Pauliac Katia Ripamonti Organizing Secretariat Veronica Marchiafava – GdC-Associazione Italiana Colore Michele Russo – Politecnico di Milano Scientific committee – Peer review Fabrizio Apollonio | Università di Bologna, Italy Gabriel Marcu | Apple, USA John Barbur | City University London, UK Anna Marotta | Politecnico di Torino Italy Cristiana Bedoni | Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy Berta Martini | Università di Urbino, Italy Giordano Beretta | HP, USA Stefano Mastandrea | Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Berit Bergstrom | NCS Colour AB, SE Italy Giulio Bertagna | B&B Colordesign, Italy Louisa C. -

Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism

Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism Håkansson, Håkan 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Håkansson, H. (2001). Seeing the Word : John Dee and Renaissance Occultism. Department of Cultural Sciences, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Seeing the Word To Susan and Åse of course Seeing the Word John Dee and Renaissance Occultism Håkan Håkansson Lunds Universitet Ugglan Minervaserien 2 Cover illustration: detail from John Dee’s genealogical roll (British Library, MS Cotton Charter XIV, article 1), showing his self-portrait, the “Hieroglyphic Monad”, and the motto supercaelestes roretis aquae, et terra fructum dabit suum — “let the waters above the heavens fall, and the earth will yield its fruit”. -

Final Copy 2020 05 12 Leen

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Leendertz-Ford, Anna S T Title: Anatomy of Seventeenth-Century Alchemy and Chemistry General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. ANATOMY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ALCHEMY AND CHEMISTRY ANNA STELLA THEODORA LEENDERTZ-FORD A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, School of Philosophy. -

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy

Visualization in Medieval Alchemy by Barbara Obrist 1. Introduction Visualization in medieval alchemy is a relatively late phenomenon. Documents dating from the introduction of alchemy into the Latin West around 1140 up to the mid-thirteenth century are almost devoid of pictorial elements.[1] During the next century and a half, the primary mode of representation remained linguistic and propositional; pictorial forms developed neither rapidly nor in any continuous way. This state of affairs changed in the early fifteenth century when illustrations no longer merely punctuated alchemical texts but were organized into whole series and into synthetic pictorial representations of the principles governing the discipline. The rapidly growing number of illustrations made texts recede to 1 the point where they were reduced to picture labels, as is the case with the Scrowle by the very successful alchemist George Ripley (d. about 1490). The Silent Book (Mutus Liber, La Rochelle, 1677) is entirely composed of pictures. However, medieval alchemical literature was not monolithic. Differing literary genres and types of illustrations coexisted, and texts dealing with the transformation of metals and other substances were indebted to diverging philosophical traditions. Therefore, rather than attempting to establish an exhaustive inventory of visual forms in medieval alchemy or a premature synthesis, the purpose of this article is to sketch major trends in visualization and to exemplify them by their earliest appearance so far known. The notion of visualization includes a large spectrum of possible pictorial forms, both verbal and non-verbal. On the level of verbal expression, all derivations from discursive language may be considered to fall into the category of pictorial representation insofar as the setting apart of groups of linguistic signs corresponds to a specific intention at formalization. -

Alchemy Endnotes(1)

A C A P P E L L A Title: ALCHEMY Artists: Kamilla Bischof, Hélène Fauquet, Till Megerle, Evelyn Plaschg curated by: Melanie Ohnemus Venue: Acappella Vico Santa Maria a Cappella Vecchia 8/A, Naples Opening: October 11, 2018 Till: December 8, 2018 www.museoapparente.eu [email protected] \\ +39 3396134112 Alchemy (from Arabic “al-kīmiyā”) is a philosophical and protoscientific tradition practiced throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia. It aims to purify, mature, and perfect certain objects (1). Common aims were crysopoeia (2), the transmutation of “base metals” (e.g., lead) into “noble metals” (particularly gold); the creation of an elixir of immortality; the creation of panaceas (3) enabling to cure any disease; and the development of an alkahest, a universal solvent. The perfection of the human body and soul was thought to permit or result from the alchemical magnus opus and, in the Hellenistic and western tradition, the achievement of gnosis (5).(6) In Europe, the creation of a philosopher’s stone was variously connected with all of these projects. In English, the term is often limited to descriptions of European alchemy, but similar practices existed in the Far East, the Indian subcontinent, and the Muslim world. In Europe, following the 12th-century Renaissance, produced by the translation of Islamic works on science and the Recovery of Aristotle, alchemists played a significant role in early modern science (particularly chemistry and medicine). Islamic and European alchemists developed a structure of basic laboratory techniques, theory, terminology, and experimental method, some of which are still in use today. However, they continued with the ancient belief in four elements and guarded their work in secrecy including cyphers and cryptic symbolism. -

Al-Kimya Notes on Arabic Alchemy Chemical Heritage

18/05/2011 Al-Kimya: Notes on Arabic Alchemy | C… We Tell the Story of Chemistry Gabriele Ferrario Detail from a miniature from Ibn Butlan's Risalat dawat al-atibba. Courtesy of the L. Mayer Museum for Islamic rt, $erusalem. Note: Arabic words in this article are given in a simplified transliteration system: no graphical distinction is made among long and short vowels and emphatic and non-emphatic consonants. The expression —Arabic alchemy“ refers to the vast literature on alchemy written in the Arabic language. Among those defined as —Arabic alchemists“ we therefore find scholars of different ethnic origins many from Persia who produced their works in the Arabic language. ccording to the 10th-century scholar Ibn l-Nadim, the philosopher Muhammad ibn ,a-ariya l-Ra.i /0th century1 claimed that 2the study of philosophy could not be considered complete, and a learned man could not be called a philosopher, until he has succeeded in producing the alchemical transmutation.3 For many years Western scholars ignored l-Ra.i4s praise for alchemy, seeing alchemy chemheritage.org/…/25-3-al-kimya-not… 1/3 18/05/2011 Al-Kimya: Notes on Arabic Alchemy | C… instead as a pseudoscience, false in its purposes and fundamentally wrong in its methods, closer to magic and superstition than to the 2enlightened3 sciences. Only in recent years have pioneering studies conducted by historians of science, philologists, and historians of the boo- demonstrated the importance of alchemical practices and discoveries in creating the foundations of modern chemistry. new generation of scholarship is revealing not only the e7tent to which early modern chemistry was based on alchemical practice but also the depth to which European alchemists relied on rabic sources.