Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemy Journal Vol.7 No.2

Alchemy Journal Vol.7 No.2 Vol.7 No.2 Autumn 2006 CONTENTS ARTICLES Fulcanelli's Identity The Alchemical Art Planetary Attributions of Plants FEATURES New Releases From the Fire Announcements Lectures EDITORIAL From the Editor Submissions Subscriptions Resources Return to Top Some of the reliable information that we know about Fulcanelli comes from the Prefaces written by Canseliet, while other information comes The Illustration above was drawn by artist-alchemist Juliene Champagne. It is from a 1926 French edition of Fulcanelli: Mystery of the from such other Cathedrals sources as various interviews that were http://www.alchemylab.com/AJ7-2.htm (1 of 19)11/1/2006 10:14:47 PM Alchemy Journal Vol.7 No.2 Fulcanelli's Most Likely Identity - Part I later conducted with Canseliet. It almost seems as though Canseliet deliberately By Christer Böke and John Koopmans left behind a number of tantalizing clues. Editor’s Note: This article is being published in as a two part series. In Part I, the authors summarize what is known about Fulcanelli based on primary sources of information provided by his trusted confidant, Eugene Canseliet, establish an approach they will use to review whether or not several proposed candidates are in fact the true identify of the famous and mysterious Master Alchemist, and attempt to establish the date of his birth and “departure” or death. Part II of the article, to be published in the next issue of the Journal, reveals the authors’ belief about the likelihood of these candidates actually being Fulcanelli and presents their proposed answer to the question: Who was Fulcanelli? Introduction ARTICLES The 20th century Master Alchemist, Fulcanelli, is well-known to the alchemical community through the two highly regarded books that bear his name: Le Mystère des Cathédrales (1926), and Les Demeures Fulcanelli's Identity Philosophales (1930). -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

Fundamentals of Alchemy\374

Alchemia This is a long page, but the three texts below are well worth the read, I have some ending comments that I wish to share. These examples are of the Beginning stages of our Art. The first is a famous tract entitled the Secret Book . Written in the sixteenth century by someone named Artephius, who claims that at the time of his little tract he had lived about a thousand years (do remember that the Stone does not give eternal physical life, for one must pass through the three stages of life at some point, but cleanses the body of disease and fortifies it so one might live much longer than expected). This secret book is one of the most revealing texts explaining the entire process and the first process both at the same time. It is clear, concise and to the point. Note however that there is apparently no order or explanations as to which stage and substance he is writing about. It is left entirely up to the "clever young Philosopher" to discover. As we Philosophers progress and read more and more of the great texts, it becomes clearer and more precise (all of the true texts agreeing with one another albeit with different analogies and allegories). One begins to see themes suddenly arising apparently out of nowhere, a burst of new enlightenment arises and what was hidden before, becomes clear. The second text was written by John Pontanus who also claimed to find the Stone, and his text is to the point of one substance: the Sophic Fire or Secret fire . -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Magnes: Der Magnetstein Und Der Magnetismus in Den Wissenschaften Der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien Und Texte

Magnes: Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien und Texte Editor Thomas Haye (Zentrum für Mittelalter- und Frühneuzeitforschung, Universität Göttingen) Founding Editor Paul Gerhard Schmidt (†) (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) volume 53 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mits Magnes Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit von Christoph Sander LEIDEN | BOSTON Zugl.: Berlin, Technische Universität, Diss., 2019 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sander, Christoph, author. Title: Magnes : der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit / von Christoph Sander. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Mittellateinische studien und texte, 0076-9754 ; volume 53 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019053092 (print) | LCCN 2019053093 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004419261 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004419414 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Magnetism–History–16th century. | Magnetism–History–17th century. Classification: LCC QC751 .S26 2020 (print) | LCC QC751 (ebook) | DDC 538.409/031–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053092 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053093 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 0076-9754 ISBN 978-90-04-41926-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-41941-4 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Christoph Sander. Published by Koninklijke -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

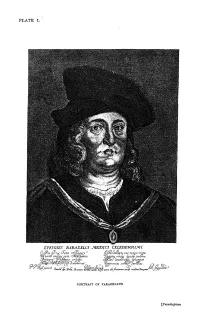

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored

ALCHEMY REDISCOVERED AND RESTORED BY ARCHIBALD COCKREN WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE EXTRACTION OF THE SEED OF METALS AND THE PREPARATION OF THE MEDICINAL ELIXIR ACCORDING TO THE PRACTICE OF THE HERMETIC ART AND OF THE ALKAHEST OF THE PHILOSOPHER TO MRS. MEYER SASSOON PHILADELPHIA, DAVID MCKAY ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1941 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS FOREWORD PART I. HISTORICAL CHAPTER I. BEGINNINGS OF ALCHEMY CHAPTER II. EARLY EUROPEAN ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER III. THE STORY OF NICHOLAS FLAMEL CHAPTER IV. BASIL VALENTINE CHAPTER V. PARACELSUS CHAPTER VI. ALCHEMY IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES CHAPTER VII. ENGLISH ALCHEMISTS CHAPTER VIII. THE COMTE DE ST. GERMAIN PART II. THEORETICAL CHAPTER I. THE SEED OF METALS CHAPTER II. THE SPIRIT OF MERCURY CHAPTER III. THE QUINTESSENCE (I) THE QUINTESSENCE. (II) CHAPTER IV. THE QUINTESSENCE IN DAILY LIFE PART III CHAPTER I. THE MEDICINE FROM METALS CHAPTER II. PRACTICAL CONCLUSION 'AUREUS,' OR THE GOLDEN TRACTATE SECTION I SECTION II SECTION III SECTION IV SECTION V SECTION VI SECTION VII THE BOOK OF THE REVELATION OF HERMES 1 Alchemy Rediscovered And Restored By Archibald Cockren THE SMARAGDINE TABLES OF HERMES TRISMEGISTUS said to be found in the Valley of Ebron, after the Flood. 1. I speak not fiction, but what is certain and most true. 2. What is below is like that which is above, and what is above is like that which is below for performing the miracle of one thing. -

Agrippa's Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia

chapter 4 Agrippa’s Cosmic Ladder: Building a World with Words in the De Occulta Philosophia Noel Putnik In this essay I examine certain aspects of Cornelius Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia libri tres (Three Books of Occult Philosophy, 1533), one of the foun- dational works in the history of western esotericism.1 To venture on a brief examination of such a highly complex work certainly exceeds the limitations of an essay, but the problem I intend to delineate, I believe, can be captured and glimpsed in its main contours. I wish to consider the ways in which the German humanist constructs and represents a common Renaissance image of the universe in his De occulta philosophia. This image is of pivotal importance for understanding Agrippa’s peculiar worldview as it provides a conceptual framework in which he develops his multilayered and heterodox thought. In other words, I deal with Agrippa’s cosmology in the context of his magical the- ory. The main conclusion of my analysis is that Agrippa’s approach to this topic is remarkably non-visual and that his symbolism is largely of verbal nature, revealing an author predominantly concerned with the nature of discursive language and the linguistic implications of magical thinking. The De occulta philosophia is the largest, most important, and most complex among the works of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535). It is a summa of practically all the esoteric doctrines and magical practices ac- cessible to the author. As is well known and discussed in scholarship, this vast and diverse amount of material is organized within a tripartite structure that corresponds to the common Neoplatonic notion of a cosmic hierarchy. -

Remarks Upon Alchemy and the Alchemists

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Research Library, The Getty Research Institute http://www.archive.org/details/remarksuponalcheOOhitc NEW THOUGTIT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION' No. REMARKS ALCHEMY AND THE ALCHEMISTS, INDICATIXG A METHOD OF DISCOVEKI^'G THE TEUE NATURE OF HERMETIC PHILOSOPHY; A^D SHOWING THAT THE SEARCH AFTER HAD NOT FOR ITS OBJECT THE DISCOVERY OF AN AGENT FOR THE TRANSMUTATION OF METALS. BEING ALSO AS ATTEMPT TO RESCUE FROM UNDESERVED OPPROBRIUM THE REPUTATION OF A CLASS OF EXTEAORDIXARY THINKEES IN PAST AGES. ' Man shall not live by bread alone." BOSTON: CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY, 111 Washington Street. 1857. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, by Crosby, Nichols, and Company, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts. cambsidge: metcalf and company, printers to the tjnrversitt. NE¥/ THOUGHT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION No. PEEFACE. ED.W. PARKER, L ittle Ruc k, Ark. It may seem superfluous in the author of the fol- lowing remarks to disclaim the purpose of re vivino- the study of Alchemy, or the method of teaching adopted by the Alchemists. Alchemical works stand related to moral and intellectual geography, some- what as the skeletons of ichthyosauri and plesio- sauri are related to geology. They are skeletons of thought in past ages. It is chiefly from this point of view that the writer of the following pages submits his opinions upon Alchemy to the public. He is convinced that the character of the Alchemists, and the object of their study, have been almost universally misconceived ; and as a matter of fact^ though of the past, he thinks it of sufficient importance to take a step in the right direction for developing the true nature of the studies of that extraordinary class of thinkers. -

John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica

The Royal Typographer and the Alchemist: John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica Stephen Clucas Birkbeck, University of London, UK Abstract: John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica (1564) was a work which involved a close collaboration between its author and his ‘singular friend’ the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius, in whose house Dee was living whilst he composed the work and saw it through the press. This article considers the reasons why Dee chose to collaborate with Silvius, and the importance of the intellectual culture – and the print trade – of the Low Countries to the development of Dee’s outlook. Dee’s Monas was probably the first alchemical work which focused exclusively on the diagrammatic representation of the alchemical process, combining diagrams, cosmological schemes and various forms of tabular grid. It is argued that in the Monas the boundaries between typography and alchemy are blurred as the diagrams ‘anatomizing’ his hieroglyphic sign (the ‘Monad’) are seen as revealing truths about alchemical substances and processes. Key words: diagram, print culture, typography, John Dee, Willem Silvius, alchemy. Why did John Dee go to Antwerp in 1564 in order to publish his recondite alchemical work, the Monas Hieroglyphica? What was it that made the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius a suitable candidate for his role as the ‘typographical parent’ of Dee’s work?1 In this paper I look at the role that Silvius played in the evolution of Dee’s most enigmatic work, and at the ways in which Silvius’s expertise in the reproduction of printed diagrams enabled Dee to make the Monas one of the first alchemical works to make systematic use of the diagram was a way of presenting information about the alchemical process. -

Download PDF Version

Alchemy, astrology & the Alchemy, astrology & the occult e-catalogue Jointly offered for sale by: Extensive descriptions and images available on request All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Antiquariaat FORUM BV ASHER Rare Books Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 MS ‘t Goy 3997 MS ‘t Goy The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E–mail: [email protected] E–mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com www.forumislamicworld.com cover image: no. 7 v 1.1 · 21 December 2020 no. 14 is unavailable Fables for Christians, by one of the founders of Rosicrucianism 1. [ANDREAE, Johann Valentin].